It was not long in coming. While McKeever and Ulrich beat their retreat toward Lake Borgne to warn Jones, the first major segment of the invasion force under Admiral Cochrane had doubled the Chandeleur Islands and, buffeted by a fog-studded storm that reached near-hurricane strength, stood in toward the coast, rounded to and came to anchor between Ship and Cat Islands.

As reports of British movements began to accumulate, Lieutenant Jones maneuvered his flagship—Gunboat No. 156 was not even dignified with a name—across Lake Borgne. And, while he did, there was time for him to consider both himself and his command.

Since accepting a midshipman’s warrant in 1805, he had served continuously in gunboats, first in Norfolk and then in New Orleans, thus missing those famous frigate actions which elevated a fledgling American Navy to fame. Earlier, as a young midshipman waiting impatiently to be called to active service, he had shared the national outrage and humiliation attending Commodore James Barron’s inept surrender of the American frigate Chesapeake to the English frigate Leopard.

Called to active duty shortly after the Chesapeake-Leopard affair, Jones hastened to Hampton Roads, Virginia, hoping for one of the tall ships, but found himself assigned instead to the ignominious gunboats which history would label Thomas Jefferson’s greatest maritime mistake. Gunboat duty was, of course, universally unpopular. There were no prizes, no glory—only frustration.

His first ship—Gunboat No. 10—turned out to be a veteran of the Barbary Wars. No longer even in full commission, it had been laid up in ordinary at Norfolk in 1806, and Jones arrived on board to discover he would be little more than a land-bound caretaker, responsible for defending the gunboat against dry rot and an economy-minded Administration. Later on he would accumulate the broad reservoir of experience which the impending War of 1812 would demand, but in the meantime, the young midshipman could only tackle his maudlin task with that dedicated and driving intensity which was destined to mark his entire half-century of naval service.

During the long years of apprenticeship from 1807 to 1814, however, he had learned his lessons well and now, as the groundswell rolled Gunboat No. 156 from side to side, Jones could once more review his preparations for the imminent battle and take comfort in the certain knowledge that he was one of the Navy’s most experienced gunboat commanders. And, except for improper stationing forced by the current’s vagaries, his ships were as ready for battle as their limited capability would permit. Still, from his own firsthand knowledge, he knew how ineffectual these spitkids would be when the fighting actually began.

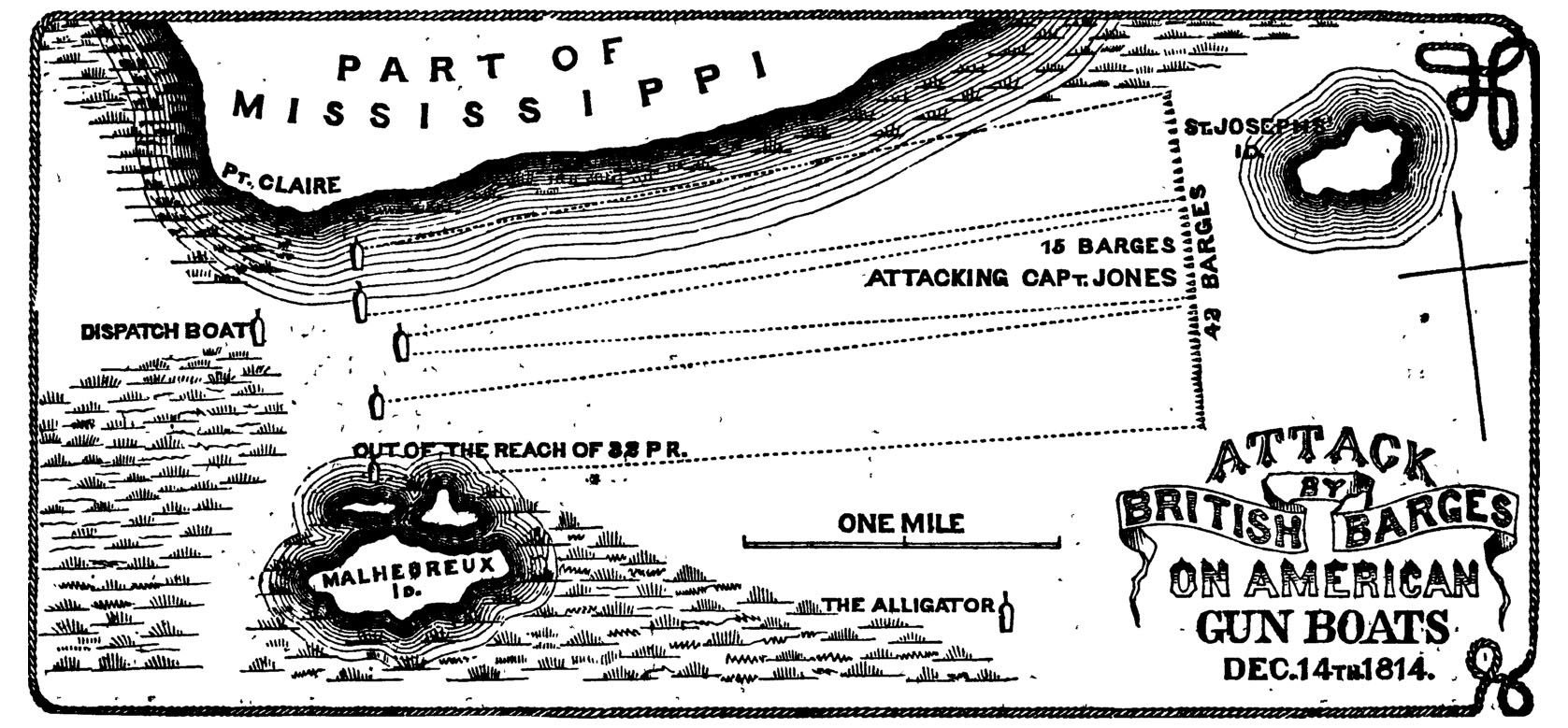

Stretched out across the Lake’s narrow entrance, roughly between Point Claire and Malheureux Island, his tiny ships blocked the maritime road to New Orleans. Springs rigged to their cables held them broadside to the approaching enemy, boarding nets were triced up, and the badly outnumbered crews stood tense and ready at their stations. Averaging 50 feet in length, five guns and 30 men apiece, the little handful of Mr. Jefferson’s gunboats awaited their British opponents.

Having been ordered to meet the English assault with nothing but gunboats, Jones had good cause to ponder the evolution of these awkward craft in the American Navy. Spawned by a combination of naiveté, frugality, and simple ignorance, they constituted the bulk of a navy, that because of its small number of real men-o’-war, was both pathetically ineffective and criminally expensive, when weighed against the royalties it paid in naval protection. Though temporarily obscured by the euphoria surrounding victories turned in by the magnificent 44-gun frigates, generally credited to Joshua Humphreys, history ultimately rendered its judgment of the sea war of 1812–1815: the British—with their balanced and powerful fleet—eventually dominated the American coasts. It was unfortunate that President Jefferson did not understand sea power as well as did his English opponents. But he did not.

Instead, he believed in “. . . hunting out and abolishing multitudes of useless officers, striking off jobs . . . eliminating dissipation of treasure and legal appropriation . . .” Gunboats seemed to Jefferson to be the ideal answer to those foreign incursions which had been descending almost daily upon America’s long coastline. In addition, they promised him one essential dividend: unlike their larger, seagoing cousins, gunboats could not fight hard battles on distant oceans, thereby provoking stupid foreign wars. To Jefferson, this factor was governing. Unfortunately for the stripling United States, neither could they stand up to the frigates and ships-of-the-line being built by other, less reluctant and wiser nations.

Nevertheless, employing gunboats as the mainstay, Thomas Jefferson and his influential but equally misguided Secretary of the Treasury, Albert Gallatin, pushed ahead with the construction of more than 170 of them.

Having already failed miserably the ultimate test of battle in the Chesapeake, that navy was about to be tried again, this time on Lake Borgne. The specific tragedy here, however, was that Lieutenant Jones and his dedicated sailors in Mississippi Sound were being asked to prove once more that which was already well-known: Mr. Jefferson’s solution was really no solution at all.

What the United States needed off New Orleans, of course, was—like that of the English—a balanced fleet: ships-of-the-line and frigates, both capable of fighting far out in the blue waters of the Gulf; brigs and shallow-draft sloops to join these big ships in defending coastal waters; finally, a sizeable fleet of gunboats for last ditch defense of the narrow water thoroughfares leading through the labyrinth of bayous to the city itself. But the infant country did not have such a fleet because an economy-minded President neither approved nor saw the necessity for “ . . . the ruinous folly of a navy.”

Plagued by the results of that Jeffersonian policy, Thomas ap Catesby Jones now faced an enemy who harbored no such illusions over the relative merits of gunboats and deep-water ships. One thing the English understood full well: when shoal water at last stopped the big ships, they needed only to hoist out their small boats—they carried large numbers of them—and continue the chase. On 14 December 1814 in Mississippi Sound, they were busily doing precisely that.

Just before 1030, when Jones again checked the British boats, first signs of renewed movement caught his attention. Their crews rested and breakfasted, they were all getting underway. Jones knew the English sailors were still far from fresh after their long, grueling pull across the Sound and, obviously, he hoped this would reduce the odds somewhat; enough, perhaps, to give him a fighting chance.

It must have been with great impatience that he estimated the distance to the enemy, well knowing that his flotilla’s survival depended upon its ability to shoot the British formation to shreds long before it ever reached boarding range. No one had to tell him that once the barges closed the gunboats in anything like significant numbers, he and his men would be in desperate trouble.

Slowly, the range shrank. When, at last, it appeared that the Long Tom mounted in Gunboat No. 23 could span the narrowing gap, Jones signalled Lieutenant Ike McKeever to open fire.

The heavy gun’s deep-throated roar shattered the quiet morning air and a 32-pound ball arced across the Lake’s surface. Plunging into the water close astern of the British line, it tossed up a thin geyser which, undisturbed by any sea breeze, fell leisurely back into the green water. Their boats undamaged, the English ignored the ranging shot and merely pulled harder for their becalmed quarry. But, because it appeared beyond the line of attackers, that harmless fountain galvanized gun crews into action on all five gunboats. Swivels, 24-pounders, howitzers, all erupted in a rolling thunder of sound, spewing an assorted storm of cannon balls and grape shot out across the water.

Here and there the Americans scored hits, cutting British sailors down and holing one or two barges which promptly capsized, dumping their struggling crews into the water before sinking. But the range was long, individual targets small, and the fire produced little overall effect. The barges pressed on.

Finally, coming within range of their own guns shortly after 11 o’clock, the British began to return the fire and, in the words of Jones’ battle report, “ . . . the action became general and destructive on both sides.”

Lossing’s Pictorial Field-Book of the War of 1812

Weary but determined, the English bored in through the hail of shot. By ten minutes to twelve, the first of their boats had closed sufficiently to make an attempt at boarding.

They converged on Jones’ flagship which had been dragged furthest out of line by the unwelcome current. Being the most exposed, she automatically became the prime target, and Captain Lockyer, seeing Jones’ predicament, took immediate advantage of it by detaching almost a third of his force to deal with the exposed gunboat. But, even with Lockyer in personal command, coordination problems dogged the assault group from the moment he ordered it forward—especially three barges which imprudently charged Jones’ gunboat ahead of all the rest.

Jones ordered his full battery trained on them. Depressing their guns, his crew fired, reloaded, and fired again. A 24-pound ball ripped out the side of one barge, another pierced the bottom of its companion, grape shot swept through the crew of the third, killing or wounding them all.

Before Jones could pass a “Well Done” to his sharpshooters, however, four more barges plowed through the wreckage of the shattered initial assault wave, heading straight for his flagship. Again, smoking American guns stammered out an irregular but deadly chorus, decimating the second attack wave as quickly as the first. With the battle only moments old, seven stout British barges had already been transformed into chunks of splintered timbers which, intermingled with broken bodies, swirled and drifted uncertainly under the current’s irresistible influence.

But the battle was not one-sided. The battered Englishmen had not suffered all the casualties.

British musket balls whistled through the little gunboat’s boarding nets and across her deck, and American sailors clutched at gaping wounds. A ball tore into Jones’ left shoulder, slamming the young commander to the deck. He lay stunned and bleeding until Master’s Mate George Parker took command of the gunboat and had his blood-drenched captain moved to comparative safety.

Gunboat No. 156, center, with Lieutenant Jones on board, was in the most exposed position as the swarm of British boats and barges closed in for the kill.

Minutes later, a third attack developed. For Gunboat No. 156, it would be the last.

A half-dozen carronades and a hundred muskets rained covering fire on the flagship. Seven barges closed in from seven different directions, grapnels clawing at the gunboat’s railing as the attackers warped themselves alongside. Scrambling upward, English tars clutched at the boarding nets and slashed their way through. Close behind, other sailors and soldiers swarmed through the broached netting and on to the deck.

The end came swiftly. But, just before it did, another ball cut down the little gunboat’s second commanding officer. Seriously wounded, George Parker collapsed at almost the same spot as his predecessor. It was shortly after noon. Gunboat No. 156 was in British hands.

In the meantime, Lockyer’s remaining barges—divided into two assault divisions—closed around the rest of Jones’ beleagured flotilla. General fighting erupted all along the line; barges, pinnaces, and gigs attacked singly and in twos, forcing the meager number of American guns to divide their fire. Inexorably, the English musketry thinned out the gunboats’ crews and, as the American defense faltered, British seamen squirmed up the sides of the gunboats and poured through fresh-cut holes in the boarding nets.

On board Sailing Master Ferris’ Gunboat No. 5, a 24-pound ball slammed into the bulwark where it ripped a huge, gaping hole before ricocheting across the deck amidst a shower of jagged splinters. A ball that size could only have come from one of the gunboats, but a quick swing of the head would have assured him that American colors still flew from all five. Not until he traced the ball’s path back over the deck and across the water would he realize that one of the flagship’s guns was pointed directly at him. The 24-pounder belched forth a cloud of acrid, gray smoke and a second ball whined over the deck of No. 5, this one falling harmlessly into Lake Borgne. Clearly, No. 156 had fallen to the British and they were fighting her under American colors.

At almost the same instant, a surprised Lieutenant McKeever discovered that his Gunboat No. 23 was also being battered by fire from the flagship. He barked an order to bring his big 32-pounder around so it could return the fire. The gun was still swinging when the flagship’s colors at last floated down and, belatedly, the Cross of St. George climbed the halyard to the 156’s peak.

For another 30 minutes the fight raged, slowly diminishing in intensity as the gunboats, one after the other, fell to the attackers. By 1240, only McKeever’s No. 23 still held out.

His solitary and desperate resistance did not last long. Shortly after 1300, surrounded by British barges, bombarded by the other gunboats—all now in British hands—McKeever gave up the fight. Abruptly, the battle on Lake Borgne was over. The maritime highroad to New Orleans lay wide open.

Shoved along by the swiftly moving current, carnage from the short, fierce encounter drifted across the face of Lake Borgne. And the Royal Navy could count itself triumphant in yet another sea fight—though the cost had been appallingly high. Lieutenant Thomas ap Catesby Jones, on the other hand, had suffered a humiliating defeat, losing all seven of his ships—and one-third of his men—in the two-hour fight.

Now, although a prisoner of the British, cut off from further news of the campaign, and grievously wounded as he was, Jones continued to buy time for Jackson to prepare New Orleans’ defenses. When the British questioned him on board the Gorgon, Jones reeled off a description of American strength, in and around New Orleans that quite obviously surprised Cochrane. In particular, Jones’ listing of men and guns at Fort Petites Coquilles—especially when this intelligence was seemingly confirmed by two fishermen the British subsequently captured at the mouth of Bayou Bienvenue—convinced the English admiral that the shorter route (past the Rigolets and across Lake Pontchartrain to New Orleans’ back door) could not be forced. He therefore chose Bayou Bienvenue as the landing site and Pea Island—40 long miles away—as the staging area.

Altogether, Jones’ actions are generally believed to have bought Jackson nine crucial days which he would not otherwise have had.

Using every precious minute; with the help of the remnants of Commodore Patterson’s navy and a spurned but not alienated Jean Lafitte; Old Hickory routed the British assault troops on 8 January 1815. He saved New Orleans.

As the Redcoats fell back on the Gulf Coast and the boats which would return them to the safety of their armada offshore, an uninformed and disconsolate Jones fought for his life on board HMS Gorgon. Not until 12 March 1815—long after his release—was he able to take pen in hand, “Having sufficiently recovered my strength . . . to report the particulars of the capture of the division of United States’ gun-boats under my command.” To his superiors, he left the judgment of his conduct:

Enclosed you will receive a list of the killed and wounded, and a correct statement of the force which I had the honour to command at the commencement of the action, together with an estimate of the force I had to contend against, as acknowledged by the enemy, which will enable you to decide how far the honour of our country’s flag has been supported in this conflict.

That judgment was rendered by a Navy court of inquiry convened at the Naval Arsenal, New Orleans, in May. After a full and detailed review of the battle, the court reported its findings to Secretary of the Navy Crowninshield:

With the clearest evidence for their guide, the court experience the most heartfelt gratification in declaring the opinion, that Lieut. Com. Jones, and his gallant supporters—Lieutenants Spedden and McKeever, Sailing Masters Ulrich and Ferris—their officers and men, performed their duty on this occasion, in the most able and gallant manner, and that the action has added another and distinguished honor to the naval character of our country.

Jones had failed, of course, to stop the British. In the attempt, he had lost his entire squadron and had been himself severely wounded. Only by the narrowest of margins did he escape death, and for the rest of his life he carried that British ball lodged in his shoulder. During those first, long, pain-filled days in the cramped cockpit of the Gorgon, he probably fended off his physical agony by searching for some single bright spot in the whole affair. And just as probably, he searched in vain. This is, of course, not surprising.

After all, the principals in any given battle are seldom able to accurately assess the results of their actions. They are too close to the event itself. And it matters not whether that principal has just scored an apparently astounding victory or has suffered what seems then to be an ignominious defeat.

The passage of time makes the difference. For time supplies perspective, the one ingredient indispensable to sound judgment of success or failure. In the case of the Battle on Lake Borgne, perspective transforms apparent defeat into certain victory. Once this engagement is no longer viewed simply as a small, isolated naval encounter, once it is cemented into the colorful and complicated mosaic that is the Battle of New Orleans, Jones’ tactical defeat—there can be no argument on this point because he was completely and convincingly beaten—assumes the stature of a major strategic victory. His ill-starred defense of the sea approaches to New Orleans made a savior of Andrew Jackson by granting him the one thing he most needed to throw back the British assault on the Crescent City: time. With the days Jones bought for him, he succeeded. Without them, he surely would have failed.

That is not to say that Jones’ actions alone made the victory at New Orleans inevitable. They did not. Many other factors were involved, not the least of which was the important role played by Commodore Patterson and the rest of his command: the Louisiana and the Carolina. These two ships, perhaps, highlight the difference between the Chesapeake Bay and New Orleans. In the first instance, an amphibious assault was opposed by gunboats alone. They could not stop the big ships, and Washington was occupied, the capitol burned. At Lake Borgne, the gunboats could not stop the big ships, either. But the indomitable spirit of their crews did permit them to delay the small boats of the assault force, and Jackson, with the help of the Louisiana and the Carolina—types of ships not present in the Chesapeake—was able to convert that delay into victory.

But, above all, it seems clear that Jones’ defeat spelled complete and final bankruptcy for the Jeffersonian naval policy. Admittedly useless on the high seas, the gunboats had now demonstrated once again that, without the close and direct support of larger ships, they were patent failures at the one task for which they were designed. As Mr. Jefferson foresaw, they could not fight hard battles on distant oceans. But, as Mr. Jefferson did not foresee, neither could they successfully fend off assaults on our coasts delivered by nations with leaders more understanding of maritime realities. The battle of Lake Borgne therefore provides the final denouement of the Jefferson-Gallatin theory of naval strategy, and the United States Navy was off to a rather inauspicious start as the nineteenth century began.

As for Jones, he emerges from the defeat on Lake Borgne as a hero. Together with his men, he battled his way into the select company of valiant American warriors who, though beaten on the field of combat—suffering unquestioned tactical defeat—nevertheless gained resounding strategic victories for their countrymen; victories which prepared the way for the ultimate triumph of American arms.