The air forces’s training was also divided into four phases and required precision night formation flying at low altitudes. The composition of the force complicated this mission because some of the aircraft were required to perform at the extremes of their capabilities. The Son Tay Report states that “this demanded the installation and use of special equipment as well as the development of new tactics and procedures before the Task Group could become mission ready.”

The composition of the air force task group included two Combat Talon C-130s to provide precise navigation to the target area. One C-130 was designated to escort the five HH-53s and one HH-3 carrying the assault force. The other C-130 led the five A-1s that were used to provide strike force and air cover. (General Manor later stated, “The primary reason for the second Combat Talon was for redundancy in the event the first [C-130] was lost due to mechanical or other troubles. Redundancy was planned into every phase of the air elements.”)

During Phase I (preparation phase) personnel were selected for the mission, deployed to Auxiliary Field 3, and put through complex formation flying to determine their proficiency. In Phase II (specialized training) the HH-3, UH-1, and C-130s conducted day and night formation flying and full-mission profiles. (The UH-1 was designated as an alternative insertion platform in the event the HH-3 was unable to land in the compound owing to the limited size of the landing zone.) During Phase III (joint training phase) actions at the objective were rehearsed, including aerial and ground rescue operations, objective area tactics, emergency procedures, and full-mission profiles. A delay in the execution window from 21 October to 21 November allowed time for additional training (Phase IV) and included continued rehearsal of the basic and alternate plans.

For the training and execution, a forward-looking infrared (FLIR) system was installed aboard each C-130, and an additional navigator was added to the crew to improve precise navigation to the target area. Additionally, ground acquisition responder/interrogator (GAR/I) beacons were used to assist the C-130s in determining their location over the ground.

In the course of training, some important lessons were learned. Formation flying for the air forces was particularly challenging. The C-130 and either the HH-3 or the UH-1H were both required to exceed their normal limits. The helicopters flew in a draft position, maintaining a speed of 105 knots to keep up with the C-130, which had to fly at 70 percent flaps. At those slow speeds the C-130 had Doppler reliability problems. These problems were overcome by both the FLIR and GAR/I beacon, which added to the reliability of navigation. The narrow operating envelope of the HH-3 meant only essential fuel and equipment could be carried. As tactical requirements increased the size of the assault team, particular attention was paid to weight reduction. After numerous trials it was determined that flying the UH-1H in formation with a C-130 was “not within the capability of the average Army aviator,” but after intense training “the tactics of drafting with HH-3 and UH-1H [were] proven and [could] be applied in future plans.”

Another minor problem developed when it was found that the C-130 and A-1 strike force was not capable of maintaining formation with the lead assault force of C-130s and helicopters. A plan was devised to allow the A-1s to make circles or S-turns to remain in contact with the lead helicopter force. This later resulted in the decision to separate the two formations and allow them to arrive on target at a predesignated time.

According to the after-action report, throughout the training, air force “tactics and techniques were in a constant state of revision and modification until the full-dress rehearsal in early October. All missions were jointly briefed and debriefed with every element that participated represented. The building-block concept was constantly stressed and emphasized and practiced. [The air element] would practice each segment separately and single ship, if feasible. Ballast was carried to match planned flight gross weight. Formations were flown at density altitude expected to be encountered … Frequently a mission would be flown in the afternoon, and after a debrief and discussions of problems with corrective actions, the mission would be repeated after dark. During the proper phase of the moon, some missions were flown as late as 0230 in the morning to achieve as realistic lighting as possible.”

By the time training was completed on 13 November 1970, “every facet of the operation [was] exercised [totaling] more than 170 times … and over 1000 hours of incident-free flying [were] conducted primarily at night under near combat conditions.”

On 10 November 1970 the force deployed to Thailand fully prepared to conduct the mission that lay before them.

THE MISSION

The deployment to Thailand was conducted in two phases. On 10 November the two C-130s left Eglin Air Force Base under cover of darkness, and they arrived at Takhli RTAFB on 14 November. In staggered flights, the remaining personnel and equipment were flown by C-141s on 10, 12, and 16 November. The helicopters and A-1s used during training were left in CONUS, and replacement aircraft were provided by forces in Thailand. Appropriate cover stories were disseminated to prevent “espionage and sabotage from interfering with the movement of the force, to insure surprise, and to deny information regarding the movement.” In Thailand, security surveys were conducted at both Takhli and Udorn (the helicopter-staging base) RTAFBs, and secure working areas were established and maintained throughout the final stages.

On 18 November the force was assembled in the base theater at Takhli, where Manor and Simons presented a joint air and ground operations brief. Up to this time only those personnel directly involved in the planning knew what the objective was and where Son Tay was located. Although this brief was fairly extensive it did not include the exact name and location of the POW camp. Following the formal brief, the platoon leaders read the official operation plan and reviewed the schedule of activities for the remaining three days. That evening there were more staff and platoon meetings that included partial mission briefs by key individuals.

At 0330 local time on 19 November, Manor received a red rocket (flash execute) message giving him approval to launch the mission as planned. Unfortunately, the weather situation had deteriorated since the force had arrived in Thailand. Typhoon Patsy was about to make landfall over the Philippines and was expected over Hanoi within twenty-four to forty-eight hours. It was essential for the success of the mission that the air element have a five-thousand- to ten-thousand-foot cloud ceiling en route to Son Tay and suitable moonlight for the ground operations at the objective. Additionally, the coastal ceiling off the Gulf of Tonkin had to be seventeen thousand feet for the navy to conduct their diversionary air raid. Manor received a detailed weather brief the afternoon of the nineteenth, and based on that forecast he made the decision to launch the raid on the twentieth instead of the twenty-first.

The ground force spent the nineteenth conducting equipment checks, range firing, and receiving SAR and E&E briefings. On 20 November a final briefing was conducted in the base theater. “A route briefing and target briefing was given to include the geographical location, the name of the target, its relation to Hanoi’s location [cheers went up] and specific instructions concerning the conduct of force in the target area. Included were: decisive action, importance of time to success, care of wounded, SAR operations, and fighting as a complete unit in case of emergency actions.”

Following the brief, the ground force moved to the hangar for a final equipment check and to await onload. An advanced party had flown to Udorn earlier in the evening to load the helicopters with special clothing for the POWs and extra batteries and equipment for the ground force. Manor had departed earlier in the day for his command post located at Monkey Mountain just north of Danang. He later reported that “the reason Monkey Mountain was chosen was because it was a communications hub, and it had some special communication put in for [Manor’s] use.”

In the three days preceding the launch, the air elements were also busy checking aircraft and making final preparations. The two C-130s had arrived on the fourteenth and were test flown for systems checks on both the sixteenth and seventeenth. The 3d Aerospace Rescue and Recovery Group redistributed HH-53s within Southeast Asia so that ten were available at Udorn RTAFB on 15 November. By 17 November all HH-53s were mission ready. Two CONUS-based EC-121T airborne radar platforms were prepositioned at Danang, South Vietnam, for support of the mission and were ready by the seventeenth of November. The A-1 strike aircraft used for the mission were based at Nakhon Phanom RTAFB, Thailand. The A-1 crews from CONUS were moved to Nakhon Phanom and conducted system checks throughout the final three days. The aircraft realignment was conducted using routine daily frag orders or operational patterns. This helped maintain a low profile, and was consistent with the security posture throughout the training and deployment.

At 2125 on 20 November 1970, the ground force departed Takhli by C-130 and after an uneventful flight arrived at Udorn. While at Udorn the ground force transferred to the five HH-53s and one HH-3. At approximately the same time, the A-1s departed Nakhon Phanom RTAFB to effect the rendezvous over Laos with the ground force aircraft. The aircraft were designated as follows:

In addition to the above aircraft there were also a ten-aircraft MiG combat air patrol (CAP) provided by the 432d Tactical Reconnaissance Wing at Udorn (F-4s), six F-105Gs (SAM and AAA suppression) provided by the 6010th Wild Weasel Squadron at Korat RTAFB, two EC-121T College Eye early warning and command and control aircraft, two Combat Apple (airborne mission coordinator aircraft) from Kadena Air Force Base, Okinawa, one KC-135 radio relay aircraft, ten KC-135 reserve tankers from U-Tapao RTAFB, and a three-aircraft carrier diversionary strike force which included seven A-6s, twenty A-7s, twelve F-4 and F-8 aircraft, six ECM/ES-1s, and fourteen support aircraft. In all over 116 aircraft participated in the operation, taking off from seven airfields and three aircraft carriers.

The Route of the Son Tay Raid Force.

At 2256 on 20 November, the ground forces aboard their designated helicopters departed Udorn to begin the flight to Son Tay. Immediately after takeoff, an unidentified aircraft passed through the formation on a reciprocal heading, causing the helos to disperse. This created only a momentary delay before the helos rejoined in formation. The plan called for the helicopters (led by one C-130) and the A-1s (following the second C-130 out of Nakhon Phanom) to rendezvous over Laos. This provided an in-flight refueling point for the helos and allowed the two elements to join forces prior to the final leg into Son Tay.

The assault formation approached Son Tay from the west. As they arrived at a point 3-1/2 miles from the compound, the lead C-130 relayed a heading of 072 degrees to the helicopters and then pulled up and away, preparing to drop flares and firefight simulators. The first three HH-53s and the HH-3 slowed to approximately eighty knots while the remaining two HH-53s climbed to fifteen hundred feet to stand by as reserve flare ships and to recover POWs. The A-1s had executed their flight plan as scheduled, with the fifth A-1 dropping off over the Black River and the third and fourth A-1s establishing a holding pattern closer to the compound. The primary strike A-1s proceeded to the objective area and established a left-handed orbit at three thousand feet above ground level.

The lead C-130 commenced the flare drop on schedule at 0218. Seeing that the flare drop was satisfactory, Apple 4 and 5 HH-53s proceeded to their holding area on an island in Finger Lake (7 nautical miles west of Son Tay). At the same moment, approaching the coast from the east, the navy diversionary raid was in progress, which “utterly confused the enemy defenses,” focusing their attention away from Son Tay.

As the helos approached the objective area, Apple 3 (the gunship HH-53, which was the lead helo in the formation at this time) began a firing run on what appeared to be the compound. As he approached the target, however, the pilot realized it was not the correct location, and he turned left toward Son Tay. The HH-3 following immediately behind Apple 3 also turned north. Unfortunately, Apple 1 (containing Colonel Simons’s support group) landed in a field outside the wrong target. Behind Apple 1 was Apple 2, which contained Sydnor and the command and security group. The pilot of Apple 2 immediately recognized the error and proceeded north behind Apple 3 and the HH-3.

At 0218, Apple 3 commenced his firing run on the Son Tay guard towers. As their aircraft flew between the two wooden structures, the door gunners in Apple 3 opened fire, destroying the watchtowers instantly. After completing the firing run, Apple 3 proceeded to a holding area 1-1/2 nautical miles east of Finger Lake and awaited orders to return and pick up POWs.

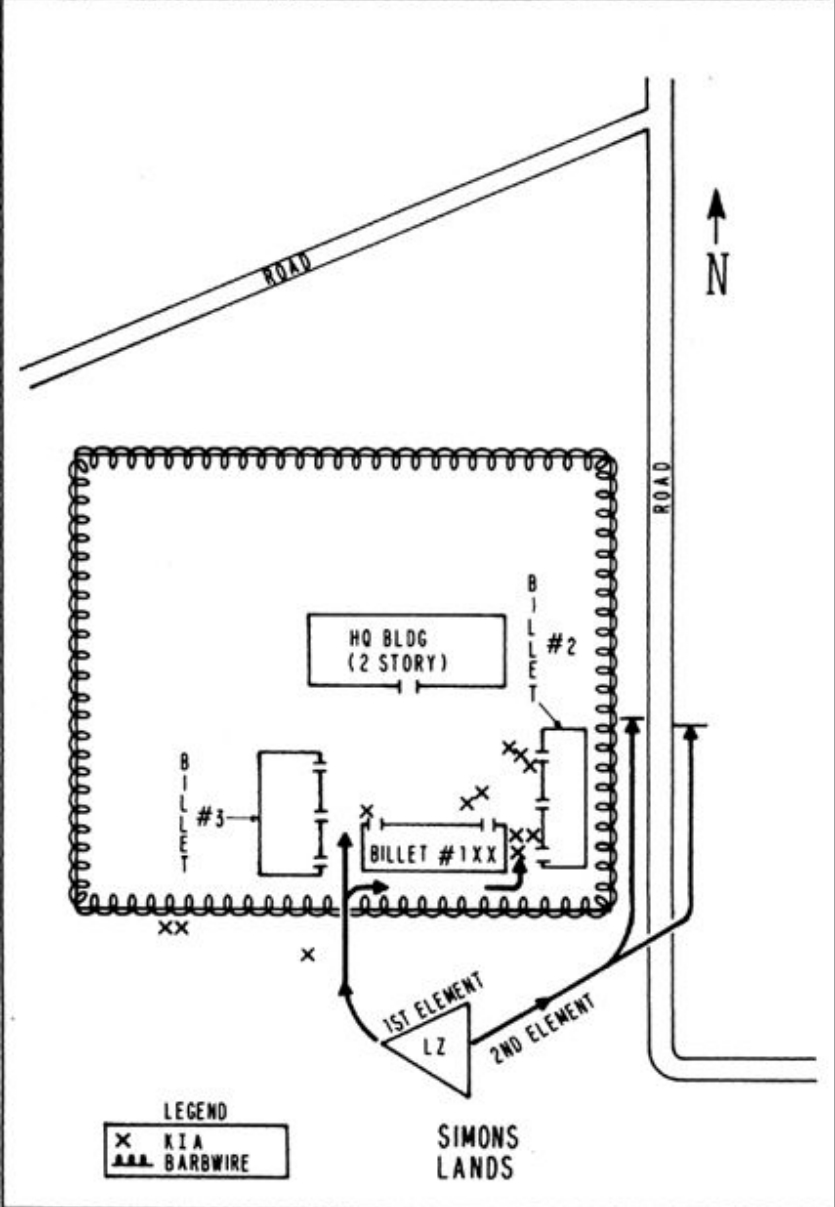

Banana 1, the HH-3 with Capt. Richard Meadows and the assault group, made a west-to-east approach crossing the west wall. The door, window, and ramp gunners began firing on their areas of responsibility as the helo executed a controlled crash into the compound. The trees in the LZ had grown significantly since June when they were originally photographed. The blades of the HH-3 severed several small trunks and sheered the tops of the others. The impact of the landing was so violent that the door gunner was thrown clear of the aircraft but landed unhurt. Once on the ground the assault group’s mission was “to secure the inside of the POW compound, to include guard towers, gates, and cell blocks and to release and guide POWs to the control point.”

The group was divided into five elements: a headquarters element with the mission to secure the south tower and latrines and provide command and control; Action Element 1, which was to clear the cell blocks and north tower; Action Element 2, which was to provide cover for the third element; Action Element 3, which was to clear the front gate; and the air force crew, which would assist in POW handling.