The French invasion of Milan, 1513

By the time this treaty with Venice was concluded, Louis XII, King of France (1498–1515), was rid of one of his most determined opponents. Julius II died during the night of 20 February 1513. The new pope was Giovanni de’ Medici, who took the title Leo X. Much younger than Julius, he was not so belligerent and was far more subtle and changeable in diplomacy. Those who dealt with him would find him hard to read, except they soon discovered his fixed purpose to elevate the Medici into a princely dynasty: domination over Florence was not enough. Inevitably, his elevation to the papal throne strengthened his family’s position in Florence, and Leo would effectively dictate Florentine foreign policy.

As he prepared to try to recover Milan, Louis could not be sure what the new pope would do, nor count on the Florentines as allies. He might have hoped to have neutralized at least one opponent in Italy, making a truce with Ferdinand in April for a year. But the truce covered the border war between France and Spain, not Italy, so Ferdinand could still oppose the French there. Nevertheless, Cardona had already been ordered to return to Naples with the army, leaving the infantry behind in the pay of others, if possible.

Cardona had not left before the French invaded Milan. Under the command of La Trémoille and Giangiacomo Trivulzio, the French troops – 1,200-1,400 lances, 600 light horse and 11,500 infantry – crossed the Alps and mustered in Piedmont in mid-May, with 2,500 Italian troops. In late May Massimiliano was reported to have 1,200 Spanish and Neapolitan men-at-arms, 1,000 light horse, 800 Spanish infantry, 3,000 Lombard infantry and 7,000 Swiss. But Cardona, having sent troops to help Massimiliano defend the north-west of the duchy, quickly withdrew them, thus facilitating the rapid French advance. He kept his men at Piacenza, which he had taken over with Parma for Massimiliano after the death of Julius. In order to secure the pope’s support against the French, Massimiliano agreed to give them up to Leo, but no papal troops were sent to help him. The duke was left with the Swiss and what Lombards rallied to his defence. On the other side, d’Alviano was under orders from Venice to join up with the French only if the Spanish joined up with the Swiss. The Venetians were confi dent that, lacking men-at-arms, the Swiss alone should not pose much of a problem for the French, and the campaign would soon be over.

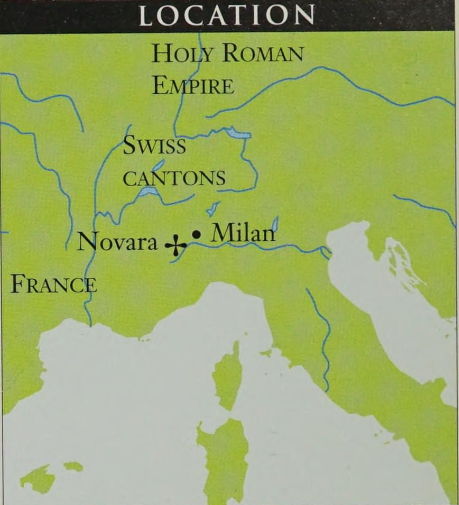

By early June, the French had overrun much of the west of the duchy. In Genoa, with the aid of a French fleet, the Adorno and Fieschi deposed Doge Giano Campofregoso and Antoniotto Adorno became governor there for Louis. In the east, the Venetian army under Bartolomeo d’Alviano took Cremona; Lodi and the Ghiaradadda rose against Massimiliano. The city of Milan, where a French garrison still held the fortress, was in confusion, waiting to see the outcome of the campaign. Only the areas around Como and Novara, where the Swiss were concentrated, still held for Massimiliano, who was at Novara.

The Battle

Throughout the winter, Louis had been trying to come to an accord with the Swiss. The seriousness of his intent was signalled by his sending La Trémoille and Trivulzio to Lucerne to conduct the negotiations, and his ordering the surrender of the fortresses of Locarno and Lugano to the Swiss. Happy to have the fortresses, but not to have the French back in Milan, in response to the invasion the Swiss rapidly organized and despatched several thousand reinforcements. These headed for Novara; news of their approach made La Trémoille decide on 5 June to raise the siege of the city that had just begun. A column of 7,000-8,000 Swiss skirted the French positions and entered Novara that day, to join the 4,000 already there with Massimiliano.

By nightfall, the French had travelled only a few miles, and the units made camp where they halted, dispersed as they were for the march. Consequently, they were ill-prepared for the attack launched by the Swiss before dawn. The Swiss had little artillery and only a few light horse with them, and the terrain, divided by ditches bordered by bushes, could have favoured the defenders had they had time to take position behind them. But the Swiss kept their disciplined battle order under fi re from the French artillery and overcame the infantry. The stiffest resistance they encountered was from about 6,000 landsknechts, who took the heaviest casualties when they were left to fight alone after the French and Italian infantry were routed. The French men-at-arms made little effort to defend them; the ground was not suited to the deployment of heavy cavalry. Nearly all the French horse escaped unscathed, abandoning their pavilions and the baggage train to the Swiss. Their artillery was captured too, and the elated Swiss dragged it back to Novara, with their own wounded men.

The battle of Ariotta (Novara) marked the zenith of the military reputation of the Swiss during the Italian Wars. Around 10,000 men, the majority of whom had reached Novara only hours before after several days’ march (and without waiting for 3,000 further reinforcements who were hard on their heels), with virtually no supporting cavalry and very little artillery, had routed a numerically superior French army, including a contingent of landsknechts almost as large as the main battle square of around 7,000 men the Swiss had formed, over terrain ill-adapted to manoeuvring such a large formation in good order. It was a tribute to the training and discipline, as well as the bravery and physical hardiness, of the Swiss infantry. The element of surprise had of course helped them, together with the fact the French army had been so widely spread out and had not prepared a defensive position, but this did not detract from the achievement of the Swiss or the humiliation of the French.

After the rout of the French army, the Spanish finally joined the Swiss to drive them out of Italy. Cardona sent 400 lances under Prospero Colonna to support Massimiliano. He also sent Ferrante Francesco d’Avalos, marchese di Pescara, with 3,000 infantry and 200 light horse to Genoa to assist the Fregoso faction in deposing Antoniotto Adorno on 17 June and replacing him with Ottaviano Campofregoso as doge. This displeased the Swiss, who had already made advantageous terms with Adorno. The Swiss took Asti, advanced in Piedmont and pillaged much of Monferrato.

It was evident that Louis could not send another expedition to Italy that year. In France, he was facing an invasion in the north by Henry VIII of England and Maximilian; Henry took Thérouanne and Tournai, and in August inflicted another humiliating defeat on the French at Guinegatte. That month the Swiss invaded Burgundy, laying siege to Dijon. La Trémoille made a treaty with them promising large payments and renouncing the king’s claim to Milan. The Swiss withdrew, but Louis would not ratify the treaty.

More than ever, the Swiss dominated the duchy of Milan. Massimiliano acknowledged the debt he owed for the blood they had shed to secure his rule, and agreed extra payments and compensation to those who had fought for him, totalling 400,000 Rhenish florins. But he did not have the money to satisfy them, nor could he afford to pay them to attack the Venetians, as Cardinal Schinner suggested.

Swiss and Landsknechts – Rivalry and Blood-Feud

Swiss fighters were responding to several interrelated factors: limited economic opportunities in their home mountains; pride in themselves and their colleagues as world-class soldiers; and, last but not least, by a love of adventure and combat. In fact, they were such good fighters that the Swiss enjoyed a near-monopoly on pike-armed military service for many years. One of their successes was the battle of Novara in northern Italy 1513 between France and the Republic of Venice, on the one hand, and the Swiss Confederation and the Duchy of Milan, on the other. The story runs as follows.

A French army, said by some sources to total 1,200 cavalrymen and about 20,000 Landsknechts, Gascons, and other troops, was camped near and was besieging Novara. This city was being held by some of the Duke of Milan’s Swiss mercenaries. A Swiss relief army of some 13,000 Swiss troops unexpectedly fell upon the French camp. The pike-armed Landsknechts managed to form up into their combat squares; the Landsknecht infantrymen took up their proper positions; and the French were able to get some of their cannons into action. The Swiss, however, surrounded the French camp, captured the cannons, broke up the Landsknecht pike squares, and forced back the Landsknecht infantry regiments.

The fight was very bloody: the Swiss executed hundreds of the Landsknechts they had captured, and 700 men were killed in three minutes by heavy artillery fire alone. To use a later English naval term from the days of sail, the “butcher’s bill” (the list of those killed in action) was somewhere between 5,000 and 10,000 men. Despite this Swiss success, however, the days of their supremacy as the world’s best mercenaries were numbered. In about 1515, the Swiss pledged themselves to neutrality, with the exception of Swiss soldiers serving in the ranks of the royal French army. The Landsknechts, on the other hand, would continue to serve any paymaster and would even fight each other if need be. Moreover, since the rigid battle formations of the Swiss were increasingly vulnerable to arquebus and artillery fire, employers were more inclined to hire the Landsknechts instead.

In retrospect, it is clear that the successes of Swiss soldiers in the 15th and early 16th centuries were due to three factors:

• Their courage was extraordinary. No Swiss force ever broke in battle, surrendered, or ran away. In several instances, the Swiss literally fought to the last man. When they were forced to retreat in the face of overwhelming odds, they did so in good order while defending themselves against attack.

• Their training was excellent. Swiss soldiers relied on a simple system of tactics, practiced until it became second nature to every man. They were held to the mark by a committee-leadership of experienced old soldiers.

• They were ferocious and gave no quarter, not even for ransom, and sometimes violated terms of surrender already given to garrisons and pillaged towns that had capitulated. These qualities inspired fear in their opponents.