Svrlig is a small town a few kilometers northeast of Nish, and it was there that the battle for the city began on November 2nd. For three days the Serbs acquitted themselves well, but as neither casualties nor ammunition could be replaced, the outcome was a foregone conclusion. On November 5th, Bulgarian First Army units marched into Nish at the same time Kövess’ men took Kraljevo, which the Serb Government had abandoned two days earlier, when it fled to Raska. Not to be outdone, the Germans pushed out both of their flanks and joined with the Bulgarians to their left at Krivi Vir on the 5th, and with the Austrians to their right at Krusevac on the 7th. These movements, coupled with the seizure of Uzice on the 4th, meant that Serbia had lost the valleys of both the Eastern and Western Morava Rivers, depriving her of most of her infrastructure. Only the rugged, often trackless mountains of the southwest contiguous to Montenegro remained.

In Macedonia, the picture was no brighter. The French still held the Vardar Valley up to the mouth of the Cerna and had advanced up the latter stream to an obscure crossing known as Vozarci, when problems of supply dictated their halt. At this point, only the ruggedness of the terrain separated them from the Serbs at Babuna Pass, some 16 kilometers (10 miles) distant. A few days later on November 8th, they took their first Bulgarian prisoners. An advance to gain all the high ground was undertaken; this precipitated a week-long struggle against both the oncoming enemy and rain and sleet. Sarrail claimed to capture an obscure village known as Sirkovo on the 10th, and subsequently proclaimed victory in the so-called ‘Battle of the Mountain Ridges’. The fighting ended on the 14th, when the precipitation turned to heavy snow. On the same day the Serb defenders of Babuna Pass, discouraged by the enemy, the elements, and an absence of contact with the French, retired from the inhospitable and treacherous ravines and fell back on Prilep, which they reached two days later.

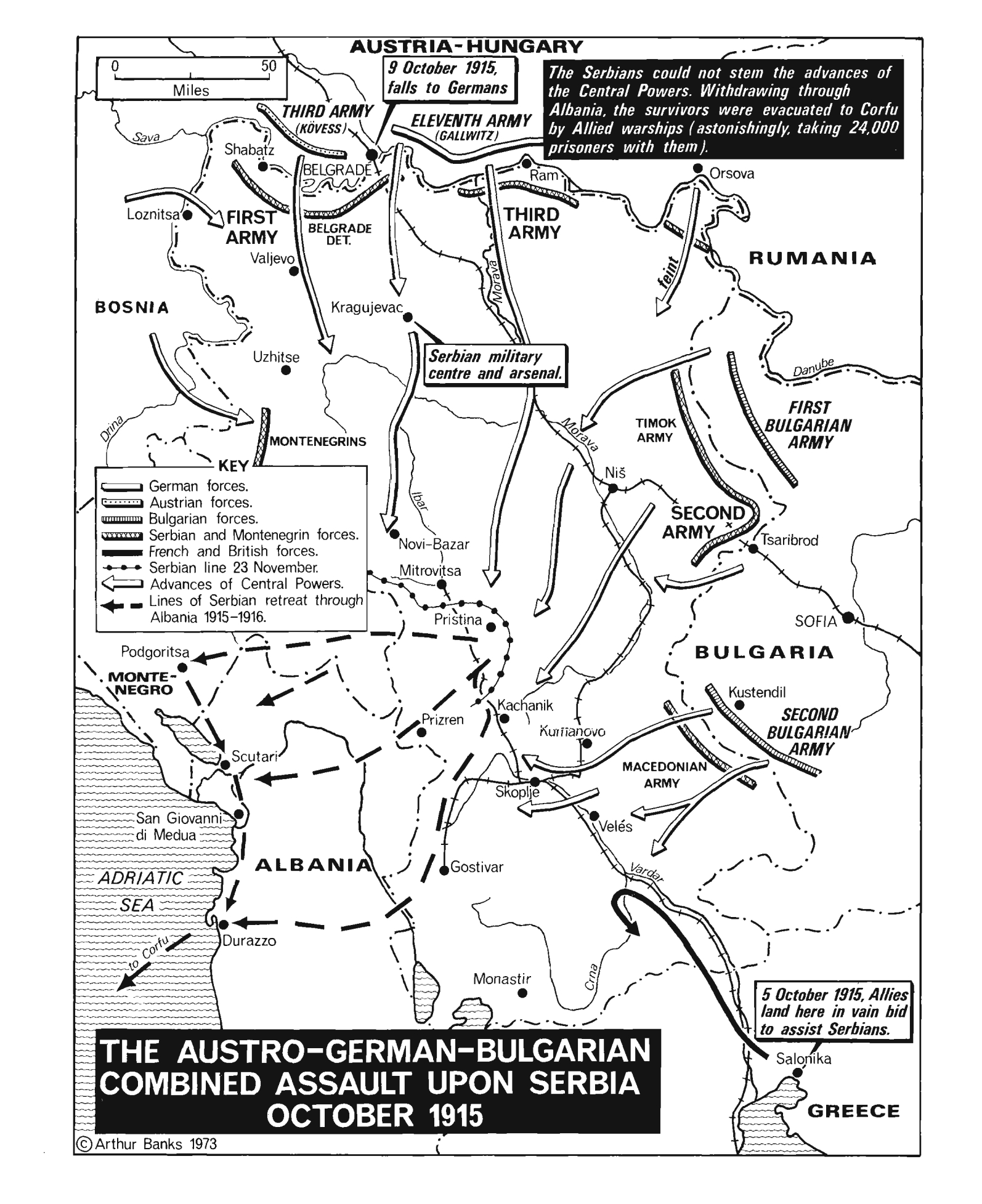

Yet again, Putnik was obliged to move his temporary capitol; this time they abandoned Raska for Mitrovica, near the legendary Field of the Blackbirds. If any place could be symbolic of Serbia’s continuing will to resist, this was surely it. One day after the evacuation, the Austrians took Raska (November 13th). Todorov, meanwhile, forced the defenders of Kacanik Pass to retreat towards Prizen, on the 15th. The Serbs were slowly but inexorably being shoved back upon the Albanian and Montenegrin frontiers, and no one could help them. The French were too few and the British were heavily engaged with fresh Bulgarian units of the newly-active Third Army and could not gain ground. For the Entente it was indeed a case of too little applied too late.

Disinterest on the part of the Entente coupled with the sluggishness of its reactions to enemy moves, nearly cost it the entire Balkans at this time. German engineers were already hard at work to repair the railroad across Serbia to Bulgaria, and in the meantime supplies bound for Turkey were shipped via the Danube to Lom, to which a spur line ran. The first of many such shipments arrived there on October 30th; soon von Sanders at the Straits was happy to receive ammunition and other support from Germany and Austria. He wrote of a 24cm mortar battery with crew coming in on November 15th, and another of 15cm following in December. A Turkish Lieutenant who kept a diary recorded “three hundred railway wagons of ammunition have arrived, as well as 21 and 24cm guns and 15cm howitzers” in his entry for November 9th.

A yawning British Cabinet met on the 19th, and decided to order three more divisions sent to Salonika, the 22nd, 26th and 27th, none of which, surprisingly, were to come from Gallipoli. Had they waited three more days—which under the circumstances would not have mattered to the Serbs—they would have had Kitchener’s initial report to help them make their decisions. His recommendation: evacuate Suvla/ANZAC but not Hellas, a classic case of the senseless half-measure.

No one need have worried. By the time Kitchener returned to Britain at the end of the month he had changed his mind again; this time he was for the complete evacuation of Gallipoli and was sour on Salonika as well. Perhaps his change of heart was at least partially due to reports that reached him en route. Beginning on the 26th, torrential rains had soaked everyone in the Aegean; after two days the downpour turned to snow and accumulated to 12 to 18 inches on the Peninsula by the 29th. Practically overnight, 16,000 cases of frostbite and exposure as well as 280 deaths thinned the British ranks.

The Turks, of course, were suffering as well. The same officer who was so thankful for reinforcement on the 9th of November was complaining about the rain and mud on the 17th. A week later, he wrote despairingly of the human sacrifice, describing a pool of dried blood with “bits of brain, bone and flesh mixed in.” On the 27th, morale was so poor that Turkish troops, when ordered to attack “refused to leave the trench and started crying….The entire unit is demoralized.” Little did they realize that time was now very much on their side.

Matters were also coming to a head in Greece, a nation ever torn between the Alliance, the Entente and Neutrality. Its neutral status having already been violated by the French and British in early October, the Germans sent a Zeppelin over Salonika in the first days of November to drop a load of bombs. If their ground was going to be fought over, most Greeks would have preferred to enter the War, but they could not agree on which side to make common cause with. On the 4th, the Zaimis Government fell in the turmoil, and Skouloudis emerged as Premier; he was a man the Entente felt they could intimidate. A ‘Pacific Blockade’ of Greece was announced on the 19th, though no one knew what that meant. They would soon learn. Essentially the Entente had decided to control not only the imports and exports of the nation, but also the use of its Navy as well. Furthermore the Greeks meekly accepted a Proclamation issued on the 25th which stated that ‘cordial relations’ between Greece and the Entente had been established. It is doubtful that King Constantine was feeling any too ‘cordial’ towards his overbearing ‘friends’.

Just before the atrocious weather of late November set in, the Ottoman Air Force was beginning to be a factor in the skies over the Straits. It was still a small, relatively inexperienced service, under the watchful eye of German Major Erich Sarno. Seaplanes began to fly over the Dardanelles Front as of summer 1915, on a fairly regular basis, and by the autumn air combat was not unknown. Two Turkish aviators flying a German Albatross CI scored the first known air victory for their country on November 30th, by downing a French Farman. For their part, the British delivered a bombing raid on the Dedeagach-Constantinople railroad on the 25th. Just how this action was supposed to injure the enemy is unclear, since the Bulgarian coast was already blockaded, and the main rail line from the interior ran from Adrianople to Constantinople, and thus was out of the seaplane’s range, except in a few places where it could easily be repaired.

Field Marshal von Mackensen was veteran enough to know when he had won a campaign, and even before the middle of November he was looking to General Headquarters for direction of further operations once the Serbs had surrendered. Hoping to spare his men the rigors of a winter sojourn around the primitive Balkan countryside, he offered his enemy peace on the 12th. For two entire weeks, there was no reply while Pasic exhausted every option in a desperate attempt to stave off defeat. Finally, on the 26th, the Serbs received a telegram from the Russian Czar, promising that his forces would soon appear in the region and save the Serbs from disaster. Thus far, Russia’s only contribution to the War in the Balkans had been a bombardment of the Ottoman capitol, but for some reason, possibly but not likely coincidence, Pasic rejected the German peace offer that very day.

The Alliance was not waiting, however, while the Serbs stalled. Its Armies had been constantly advancing toward the broken, sparsely-populated terrain of southwest Serbia. Bulgarian First Army elements entered Prokuplje on November 16th and began a five day long battle for mountainous ground separating the Morava and Ibar watersheds. The Serbs fought well in these engagements, but were outflanked by Germans driving south from Krusevac. Prepolac fell to the latter on the 21st; Tenedol Pass (Tenes Do) was approached a day later. Mackensen’s men were now perilously close to Pristina, itself only slightly east of the hallowed Field of the Blackbirds. At about the same time Austrian troops captured Novi Bazar, seat of the old Sanjak, and Novi Varos, somewhat farther west.

Yet again the Serb Government was forced to migrate, this time from Mitrovica. There were few locations in Serbia remaining to which to flee, so at length it was decided to make for Skutari in Albania, a location which had the advantage of being close to the sea. No good roads led over the trackless mountains in between, however, so the roundabout trek took several days to complete. On November 30th, the Ministers had established themselves in the foreign city, which was then under occupation by Montenegrins. Even there, the Serb officials could not have felt safe; one week earlier two Austrian cruisers, patrolling off the nearby coast had sunk a couple of small Italian vessels.

On November 23rd a major strategic decision could no longer be delayed. Serbia’s only remaining options were surrender, a fight to the death where her battered formations stood, or an attempt to escape the enemy by the sea. None were attractive, but Putnik would not surrender, and a suicidal last stand would only favor the Alliance, so reluctantly, the third option was chosen. Everyone knew it would be a terrible ordeal. The Serb troops were already exhausted, short of ammunition and low on all sorts of supplies. They would have to pass through the most bleak and rugged landscape in all the Balkans; many of the rocky, jagged ridges were devoid even of trees for firewood, a necessity in the worsening weather. And even should they reach the Adriatic, it would be in the territory of a neighboring people who were already sick and tired of being invaded by Serbs and Montenegrins. The Entente fleet might be salvation for them, but who could guarantee it would come to their aid?

Despite all the misgivings to and disadvantages of an Exodus in wintertime, the orders went out to begin it. That very day and the next (November 24th) German troops entered Mitrovica, Pristina, and occupied all of the Kosovo Plain. A last rearguard action took place at Prizen on the 27th; the defenders subsequently withdrawing down the Drin River Valley and over the Albanian frontier. Mackensen elected to not follow them. When all the prisoners from the battle at Prizen had been counted, the Germans found they had another 17,000 mouths to feed. Berlin declared the campaign over on the 28th. All of old Serbia had been overrun, and after only three years, Kosovo was once more in the grip of an invader

In Macedonia, the campaign was winding down as well. Once the Kacanik Pass force had retired to Prizen, only Vasic and his 5,000 Serbian troops remained, besides the French, to oppose the Bulgarians. When the latter reached Kruchevo on November 20th, Vasic feared for his rear and decided to fall back on Monastir, the last location of any importance in the province as yet unoccupied by the enemy. Joined there by two bedraggled regiments withdrawing from the north, the Serbs fell back to the west, towards Lakes Prespa and Ohrid and the Albanian frontier. When they had reached Resen, north of Prespa, the little army turned on its pursuers and fought a last action of the campaign. Then for reasons still unclear, they turned abruptly south, retreating along the eastern shore of the lake and into Greek territory (They were closer to the border when back in Monastir).

For their part, the French held on to their advanced and exposed positions on the middle Vardar for as long as they dared. As late as November 23rd, they were still holding their own against Bulgarian attacks, but once their Serb allies were driven off to the west, Sarrail’s men were left as too exposed on their flanks. Hoping against hope, they clung to Vozarci until the 27th, when all prospect of victory had vanished; they then evacuated their advanced positions and fell back down the Vardar, closely followed by the Bulgarians. French aviators covered the withdrawal, bombing enemy communications at Skopje, Istip and Strumitza. By the first week of December, the retreat was conducted in much more haste.

Having metaphorically burned all of their bridges to any accommodation with the Alliance, the Serbs now had no choice but to flee for their lives through the barren and inhospitable mountains of Montenegro and northern Albania. There were still roughly 200,000 of them, counting the numerous civilians who had clung to the ragged remnants of Serb military units in a desperate bid for salvation from the hated foe. Without gasoline or parts for their few motor vehicles or shells for the artillery pieces that had been saved, these were destroyed in a last-minute orgy of demolition and fire. Then, the demoralized host began its march to Skutari through the mud and snow. Four columns were formed, each of which would follow a different route along existing paths, streams and trails; there were no good roads. The remnants of the force from Prizen could at least cling to the course of the river Drin, though it wound through difficult gorges and much treeless country, where the Serbs were subjected to guerilla attacks by hostile Albanian bands. Soldiers stranded in the Jakovik (Dakovica) area first needed to scale a precipitous mountain ridge, and then descend steep, rocky defiles before reaching the Lumi Valbones, a narrow, swift-running tributary of the Drin. Those who began the journey from the Ipek (Pec) region could not hope to cross the impossible heights to the southwest, so they first moved west until they could ascend the upper Lim Valley, then stumble across the remote frontier area and down to the Moraca, which led to Lake Skutari. This roundabout route was twice the distance to the new capitol as it appeared on a map, but again, negotiating the North Albanian Alps in winter was not an option. The fourth column was the smallest. It retreated from the Bjelo Polje position on the Lim, and crawled over the ridge to the upper Tara, then to the Moraca. By December 1st, the movements resembled four lines of ants, marching inexorably toward a pre-determined destination.

Across a normally gorgeous winter landscape the Exodus struggled, battling hunger, exhaustion, privation and disease. Incredibly, it brought with it an estimated 24,000 Austrian prisoners of war, many of the bodies of whom marked the trail, along with countless Serbs, horses and oxen. “The snow covered up their misery for ever.” Wrote a British nurse serving with a Serb Relief Unit. She remembered crossing high passes with only a “2 foot track” to walk on. “On the right were snow-covered cliffs, on the left a sheer drop to the river 1,000 feet below.” Another British woman, a writer, suggested that Christ’s death by crucifixion was “gentle” compared to some of those she had witnessed. Perhaps she was right; the Good Book itself had for centuries warned against such an undertaking as the Serbs were now involved in. “Pray that your flight may not be in winter”, it admonished. Other witnesses were horrified to encounter filthy, emaciated soldiers and civilians in rags, often without boots or even shoes, surviving on raw cabbage and a few loose kernels of maize. A French correspondent claimed that between 1,000 and 1,500 of these hapless people were “lost in Albania by savage native attacks”.

Nevertheless, through all the incredible misery of the winter march, no one suggested that the majority of Serbs had lost their will to live or even to fight. Old and ill King Peter was carried by his soldiers, four at a time, in a sedan-chair complete with top and side protection from the elements; Putnik and a few other elderly, frail, high-ranking officers were afforded similar treatment. By a combination of self-sacrifice, perseverance and fierce determination to succeed, the columns of struggling human beings eventually reached their destinations, Skutari and the Adriatic Sea. It was a great accomplishment, but the price was high. The first of about 135,000 survivors began appearing in Skutari during the second week of December. The remainder had emerged from the snowy hills before the winter solstice; all others were presumed lost, and most would never be seen again, with even their final resting-places unmarked and unrecorded. It was a catastrophe of the first magnitude; however, the nucleus of a future Serb fighting force had been salvaged.

For the Alliance, only Montenegro remained to be overrun. With German support fading and being withdrawn, the task was pretty much left to the Austrians. Four German Divisions departed in late November; two more left the Balkans in December, leaving but five in Serbia. In the early days of the new month, Austro-German troops collaborated in the so-called Battle of the White Drin near Jakovik, annihilating a Serb rear-guard and taking much war material as spoils, but few prisoners. The nearby town fell on December 3rd. Ipek was captured by Austrian units three days later. The main Habsburg attack on Montenegro, however, came from the west, a two pronged blow aimed at the capitol and at Niksic, forcing the contingents defending Foca, Bjelo Polje and Berane to fall back toward the seacoast. Poor weather and the absence of good roads hampered all movement; Austrian progress was so slow that it was not until the 23rd that the capture of Berane was announced. Nikola’s soldiers were still fighting well as late as the final day of the year, when a clash with the enemy at Rozaj was hailed as a ‘repulse’ of the invaders.

As of early December 1915, all of Serbia save the southernmost reaches of Macedonia had been occupied by Alliance troops. The German Command warned the Bulgarians not to advance beyond the Greek frontier, but the latter had not yet reached any stretch of it to the west of Strumitza. On the second day of the month, French forces in the Vardar Valley began to withdraw down the Salonika railroad, with their enemies in hot pursuit. When Sarrail paused at Demir Kapu on the 5th, his men were attacked; at the same moment another Bulgarian Division was trying to cut the railroad near Strumitza Station, while simultaneously striking at the British holding a line west of Lake Doiran. In several days of fighting in dreary weather, the Entente troops were able to prevent themselves being encircled, though the British were driven from the Lake region to the railroad along the Vardar, losing 1,300 men and eight guns in the process.

Sarrail conducted himself well during the retreat, pausing to destroy bridges and even a tunnel on the rail line, a textbook withdrawal, but somewhat slower than what it should have been. Catching him again on December 8th, at Gradek, Todorov’s Bulgarians initiated a two-day battle the result of which was another French retreat in haste. On the 10th, the little Bojimia River, a minor tributary of the Vardar, had become the front line; next day Sarrail’s men linked with the British. Both contingents began to slip over the border back into Greece, ripping up the rails and firing the villages as they went. Gevgelija, the last settlement north of the frontier, was almost completely destroyed. All Entente soldiers who were not casualties were back on Greek soil by the 12th. The French had lost 3,500 men in their retrograde movement from Macedonia. Although they were tempted to do so, the Bulgarians did not cross into Greece. They did, of course, complete the occupation of Macedonia, the main prize for which they had gone to war. Monastir and the road south to the frontier were secured by December 5th. Other formations pushed hard to the west to try to fall upon the rear of fleeing Serbs, but few were ever encountered, and the westernmost settlement of the province—Debar—fell after scarcely a skirmish. With no further enemies north of Lake Ohrid to be rounded up, one Bulgarian column entered Albanian soil on the night of the 14th/15th, passing between Ohrid and Lake Prespa, presumably looking for the Serb force from Resen, which had marched east of Prespa to parts unknown. They found no Serbs but did run into a Greek regiment at Korca, where some hostile shots were exchanged before cooler heads prevailed. Probably prompted by this incident, the Greek Premier Skouloudis warned the Bulgarians, on the 17th, not to violate Greek territory. It was an outrageous stance, considering that Bulgaria’s enemies were violating Greek territory unimpeded, but without Austro-German support, Ferdinand’s government could only bide its time.

It did so, believing that once its allies had finished up with the Montenegrins and the obviously foundering enemy foothold on Gallipoli, they would surely want to drive in the Entente lines along Greece’s northern border. After all, the latest Serbian Campaign had been all about eliminating a front for Austria-Hungary and making contact with the Turks. Now that these goals had been accomplished, why would their Alliance partners want to leave them holding the bag in Greece when Romania remained to be intimidated? It was a question that not only many in Sofia were asking, but also many in Paris and London as well. None could have known that the Germans were already preparing for a mighty offensive at Verdun, on the Western Front. For the moment, all attention in the Balkans would re-focus on Montenegro, Albania and Gallipoli, where the ongoing dramas needed one final act.