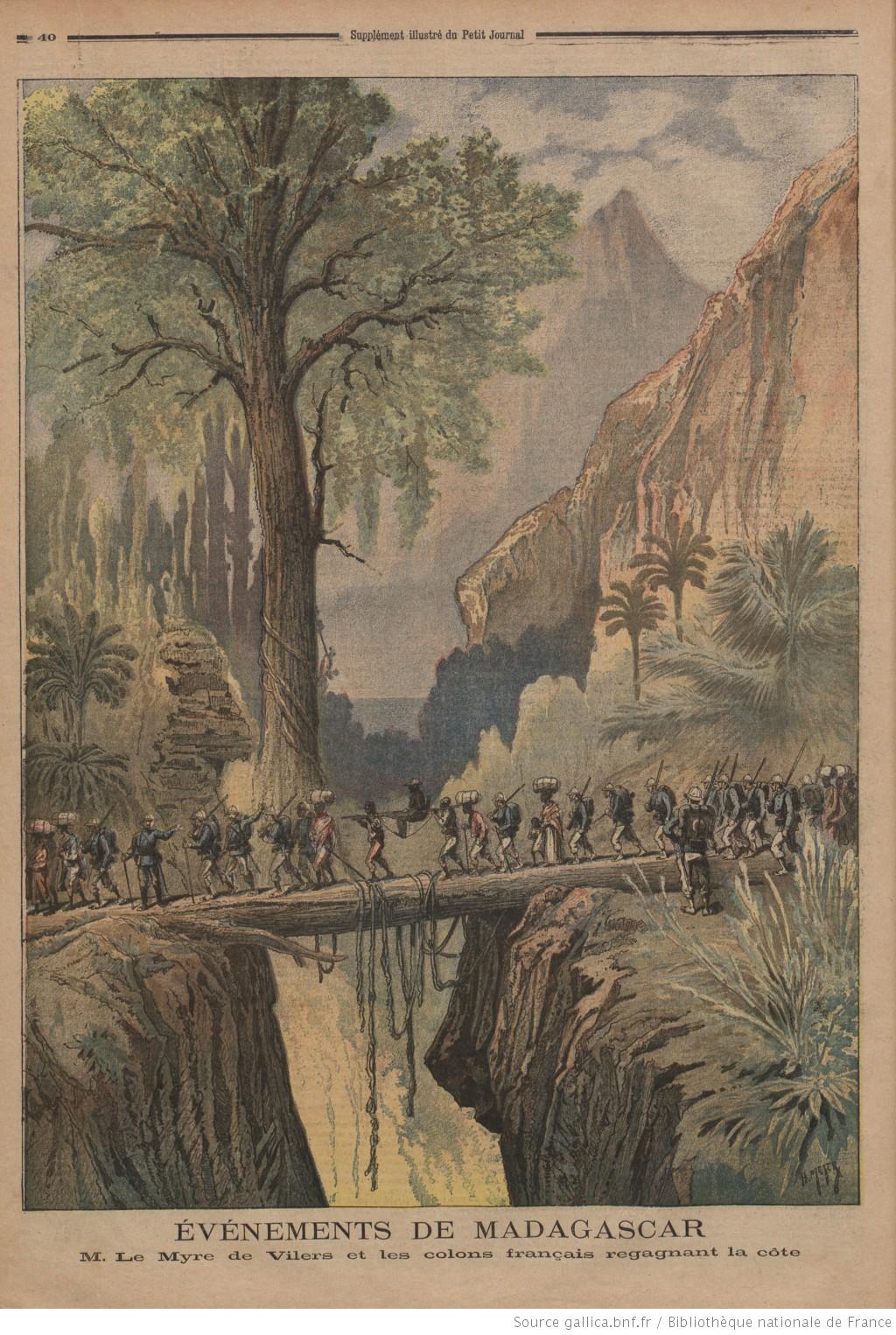

The French route to Antananarivo

A second reason why Madagascar may have produced so many suicides was simply that it was an extremely difficult campaign. Many men were obviously pushed to the brink of their physical and mental endurance, felt that they could not cope and preferred simply to do themselves in. A third reason was that, once they began, they became difficult to stop. Legion officers generally agreed that suicide, like desertion, was contagious. Once it had introduced itself into a unit, especially one whose morale was stretched as thin as that of the Legion in Madagascar, it could spread dangerously. “I know nothing which makes more of an impression than these suicides,” Langlois noted during the spate of suicides in the Legion. “A sort of derangement takes over the brain. You ask yourself with disquiet if this destructive fever is not going to seize you from one moment to another.”

Therefore, it was a great relief when the Legion marched out of camp on the 22nd because, Langlois hoped, “the march forward will perhaps chase away the black thoughts which have begun to affect us.” The route carried them beneath the rock cliffs of Angavo and into a broad valley where the red earthen village of Ambatohazano rose up like a red island amidst a green, segmented sea of rice fields. The column then climbed some chalk slopes to the plain of Ankazobe, which stretched, dusty and monotonous, to the horizon. “Our men must really have a stout spirit to make these long and tiring marches, pack on the back, without the slightest complaint,” Langlois concluded. Unfortunately, not all of them did. One legionnaire committed suicide during the night, while another shot himself in the leg, explaining to the doctor, “I can no longer march. Now you will have to carry me on a stretcher.” Unfortunately, he died of blood loss. A third simply died in his bedroll, his pipe still in his mouth. The cadavers were laid out in a shallow ravine. “We no longer bury,” Langlois noted.

As the legionnaires pushed further toward Tananarive, they entered a countryside that was almost European—villages with wide streets, pitched-roof houses, some of which had balconies and verandas, even high steepled churches. Duchesne feared that the many villages left in the rear and to the flanks might become redoubts of Malagasy resistance, and ordered his column to march in a tighter formation. But the evidence of Hova panic was all about. The hedge-lined lanes were strewn with the debris of a retreating, even a routed, army, including two cannon that had been pitched into a ravine. At least this allowed the French to advance almost without a fight, which was just as well because many of the legionnaires were on their last legs. Each morning the doctors judged a parade of unimaginable sores, bloody feces and general debilitation, a competition whose dubious winners climbed smiling onto one of the few mule-borne stretchers. On September 24, a small group of “tired legionnaires” was formed under a lieutenant. The ration of sixteen hardtack “biscuits” per soldier per day was reduced to eight, and then to four. “Those with a hearty appetite ate their day’s ration with their morning coffee,” noted Reibell. These biscuits sold for ten francs each in the light column, and sick legionnaires handed them over to those who would perform their fatigue duties for them.

The number of men simply unable to continue the march grew daily. Others fell by the wayside and never reappeared: “They were very probably massacred by the inhabitants,” the regimental diary recorded laconically. This was no fantasy—E. F. Knight saw a swarm of Hova men and women set upon an Algerian prisoner, probably a straggler, hack him to pieces and then parade his remains through the streets of Tananarive. “This was no isolated case,” Knight reported, “and it appears that two other wounded men were captured by the Hovas on the same day, and treated in like fashion.” Hova prisoners of the French seemed to have fared better—Langlois’s legionnaires impressed some of them to carry their packs. Knight was told by a Hova captured after a fight that the French simply disarmed them, gave them food, patted them on the back and told them “to be off to their homes.”

On the morning of September 26, the column climbed the slopes of Alakamisy mountain in staggering heat and looked out over the high tableland of central Madagascar to Tananarive about fifteen miles distant. “We are all crazy with joy,” Langlois wrote. “We laugh, we cry, we embrace each other without being able to stop ourselves from shouting: Tananarive! Tananarive!’ ” Admittedly, from a distance the city, bathed in sunlight, appeared as magical and welcome as the onion-domed silhouette of Moscow had been to Napoleon’s soldiers in 1812. Large walled buildings, which included the palaces of the queen and the prime minister, the royal observatory and the royal hospital, saddled a ridge 4,700 feet high, their towers and cupolas thrusting skyward as if in competition with the numerous church spires. The ruddy-colored houses interspersed with the deep green of the tropical foliage spilled down the mountainside toward a broad valley dappled with rice fields and herds of sheep.

The Algerians drove the Hovas from the neighboring peaks at the cost of one killed and seven wounded. Duchesne ordered the column to bivouac for a well-needed rest before the final push to Tananarive, to permit the convoy to catch up and, finally, to allow the general to devise his plan of attack.65 When he marched out of camp on September 28, it was to make a large turning movement to the northwest of the capital, so as to avoid throwing his troops single file across the dikes of the rice fields and up the steep slope of the Tananarive mountain. The appearance of the French, the lights of whose camp were clearly visible from Tananarive, dispelled the rumors that they had been defeated. The Hova soldiers threw up earthworks while their officers argued about the defense of the capital, and many women scurried away toward the southeast, their belongings balanced precariously upon their heads.

Yet it appeared as if the defense of Tananarive would be purely pro forma. As the legionnaires marched around Tananarive on September 28, the villagers came out to offer them food and fruit. Langlois wondered what impression the unshaven legionnaires, virtually barefoot and their clothes in tatters, must have made on the well-fed Hovas.66 From the vantage point of the British vice-consulate, Knight observed “a ridiculous pretense of defense,” fully worthy of the Grand Old Duke of York:

Bodies of men were marched up hills and then marched down again. I saw 1,000 Betsileo spearmen rush up a height at the back of the hospital; having reached the summit they waved their spears and raised a great shout, and then they quietly came down again, soon to recommence the same performance on some other height… . As soon as reality approached, as soon as the defenders found themselves within range of the French shells, and even before that, they bolted to some other position, where they could make another demonstration of battle without incurring any personal risk. It was not war, and it was not magnificent.

This was not quite true, for a vigorous attack against the Legion in the rear guard left six legionnaires wounded.

On the morning of the 29th, the French could look out over the two ridges that still separated them from Tananarive, “like two monstrous waves, that the very white lines of the enemy army fringe like foam,” wrote Langlois, “and behind rises the imposing mass of Tananarive with its monumental palaces, its thousand little red houses, its tortuous streets where huddles a white, tumultuous and agitated crowd.” On the morning of September 30, the French crowned the ridge line barely three miles from Tananarive. The day opened with an artillery barrage. The Algerians and Malagasy troops descended into the valley and then up the opposite slope. Most of the Hova troops fled in panic, but some of the guard regiments put up a fairly stiff fight defending their mountain peaks. Now only a valley stood between Duchesne and the Hova capital. Duchesne sited his artillery facing Tananarive across the valley. The French guns began to bombard the town as the infantry prepared for an assault, one to be led by the Legion. The shells knocked off a corner of the queen’s palace, and the Hova spectators cleared the vantage points of the town. Just as the order for the assault was about to be given, a white flag appeared above the palace.

The French soldiers filed down from their heights, across the narrow valley and into the town. The Legion was ordered to remain with the guns. Indeed, Langlois was furious when his soldiers were refused entry into Tananarive: “One was probably afraid that this troop of brigands called the Legion would compromise the peaceful work so happily began,” he wrote bitterly. “Poor Legion, how badly they understand you.”70 His disappointment could have been only temporary, however, for the Legion was given a prominent role in the pacification of Tananarive, including mounting guard on the queen’s palace. “Many of them could scarcely crawl along, some lay down in the streets to die, and pitiable spectacles were often to be seen,” Knight wrote of the soldiers who marched into the capital. “I met, for example, a straggler tottering into the city, almost bent double, his knapsack on his back, his rifle on his shoulder, while from the top of his helmet down to his feet he was covered with a black mass of flies, clustering on him as if he were already a corpse.” Nor was their situation improved by the neglect of many basic hygienic rules, so that in the days after the capture, burial parties were a common sight in the garrison.

The obvious question to ask is, how important was the Legion’s contribution to the two major campaigns of the 1890s in Dahomey and Madagascar? Legion historians are fond of quoting General Duchesne’s remarks made to Legion officers at the end of the campaign, that “it is assuredly due to you, gentlemen, that we are here. If I ever have the honor to command another expedition, I will want to have at least one battalion of the Foreign Legion with me.” However, one must be cautious of such statements, made in the way of thanks, or as a morale-boosting exercise. It is obviously true that the Legion played an active, even a central role in the French penetration of Tonkin, Dahomey and Madagascar. Their strength, the argument goes, was that they were better disciplined than the native troops, and more resistant than the other white troops. On the face of it, this argument seems valid. Certainly, Legion appreciations of the lack of discipline of Tonkinese or black troops reflect a sense of racial superiority and regimental pride. However, even the most avid partisans of native troops conceded that they were often recruited in haste and poorly trained, and were not disciplined to European standards—for instance, the battalion of black troops sent to Madagascar were raw recruits armed and trained on board the transports sailing to Majunga.

The problem for the Legion, as for other white troops in the Madagascar campaign, was not their discipline, but their ability to endure the debilitating tropical climates. Contemporaries noted that sickness rates in the Legion were lower than for those in other white regiments, an assessment with which historians have concurred. “The legionnaires have especially drawn attention to themselves in our recent colonial campaigns, by their endurance,” General Joseph Galliéni announced soon after the Madagascar campaign. “Their solidity under fire is equal to that of French troops, and, as their physical resistance has proven superior, they have, in reality, played a more effective role than [French troops] in the principal actions of war which have taken place during these expeditions.” In Tonkin, Dahomey and Madagascar, the superior endurance of legionnaires, which was attributed to the fact that most of their men were over twenty-five years old and therefore less susceptible to disease than were the generally younger soldiers in the marines or metropolitan units, gave rise to the saying, “When a French soldier goes to the hospital, it’s to be repatriated, a tirailleur to be cured, and a legionnaire to die.”

But while concentrating on the superior endurance of the Legion to other white troops in these campaigns, historians have failed to ask two questions. First, could the losses to sickness and fatigue have been reduced? And, second, might the French have established better and less costly principles upon which to establish their colonial expeditions? For while the Legion suffered less than other white troops, they suffered nevertheless, seriously enough to jeopardize their military performance. This author has discovered no reliable statistics for the Dahomey campaign. However, both Silbermann and Martyn had the impression that sickness reduced Legion strength by about 25 percent. The memory of so many friends left behind in Dahomey caused Silbermann to break into tears as he stepped off the ship at Oran, an event an observant journalist put down to his joy at seeing Algeria again. Those who survived the campaign were often no better off—Martyn reported that five of the 219 legionnaires evacuated from Cotonou on Christmas Day 1892 died on the return trip to Algeria, and that 69 had to be carried off on stretchers at Oran. In the autumn of 1893, as the French prepared to track down Behanzin, it was reported that so many men were sick that “the Legion could with two companies organize at best one able to campaign.” And this occurred when General Dodds planned his campaign so as best to preserve the health of his troops.

The losses to sickness in Madagascar were quite simply catastrophic: Fully 4,614 soldiers died there, roughly a third of the original 15,000 men of the expedition, and a far higher proportion than that of the white troops, plus 1,143 Algerian mule drivers, who had been shamefully neglected. These high casualty rates were quite rightly blamed on the poor organization of the Madagascar campaign, especially to the decision to build the wagon road from Majunga. Yet more might have been done to lessen casualties. Knight believed that the French “neglected the most ordinary hygienic precautions” in their camps in Tananarive. He was also appalled by the “execrable” conditions in which sick men were repatriated on the ships sailing to France, where they were confined to suffocating holds. Indeed, Reibell recorded that fully 554 soldiers died on the return trip to France, and a further 348 in France: “I was astonished to find that with few exceptions, the officers seemed indifferent to the comfort of their men, and rarely visited the fetid den in which they lay,” wrote Knight.

While Dodds certainly prescribed very strict hygienic precautions for the Dahomey campaign, it is possible that French officers, including those in the Legion, were insufficiently rigorous in enforcing them. Officers cannot be blamed for malarial mosquitoes, which were responsible for 71 percent of the deaths in the expedition. But they might have taken more care to see that their men were supplied with quinine and that they took it. In March 1893, for instance, the doctor complained that the troops in Dahomey had not received quinine. In Madagascar, Reibell complained that quinine was in short supply because it had been loaded into the transports first and therefore could not be retrieved until the ships were entirely unloaded. Also, the debilitating cases of typhoid, which caused 12 percent of the deaths, and dysentery, which caused 8 percent, were largely the products of impure water and filthy utensils. Therefore, French officers, including those in the Legion, might have increased the efficiency of their forces by paying more attention to the health and well-being of their troops. But poor hygiene was a problem throughout the French army, and not simply in the colonies.

However, given the high casualty rates of white troops even under the best conditions, would it not have been wiser for the French to campaign exclusively with native troops? For, after all, whatever these soldiers lacked in fire discipline, they more than made up in physical resistance. “My turcos [tirailleurs] have resisted more energetically the fatigues and privations than has the Legion, whose true effectives are now far below those of my battalion,” Lentonnet recorded on September 1, 1895. And this even though, he claimed, the tirailleurs had borne a larger burden in combat and fatigue. The question is, how far was Lentonnet’s pride in his Algerians and his belief that they had been far more efficient than the legionnaires in Madagascar justified?

Statistics on losses in the campaign are often confusing, but the diary of the régiment d’Algérie conserved in the war archives at Vincennes appears to bear out Lentonnet’s claims: During the march of the “light column,” one battalion of legionnaires accounted for 104 casualties, all but 14 of them suicides, missing and hospitalized, compared to 34 casualties for the two battalions of Algerian tirailleurs, all but one a combat casualty. Therefore, the Legion, which made up one-third of the regiment, accounted for three-quarters of its casualties in the light column. In the overall comparison of deaths, however, the margin of Algerian superiority is not so obvious. Duchesne reported that the Algerian regiment counted 326 deaths in course of the campaign, the vast majority due to disease, although his final report listed 604 deaths. How many of these were legionnaires is not spelled out. Sergeant Georges d’Ossau of the Legion historical service wrote in 1957 that the Legion suffered 226 deaths in Madagascar, five of which were in combat. This makes a 23 percent death rate for the battalion plus reinforcements of 1,000 legionnaires, and, based upon the figure of 604 deaths in the régiment d’Algérie, means that the Legion, with roughly one-third of the regiment’s strength, suffered 37 percent of its deaths. This would seem to indicate that the Legion fared little worse than did the Algerians.

But these figures do not include sickness, nor legionnaires who died after evacuation. The Algerians also remained longer in Madagascar than did the Legion. The figures for the light column together with the memoir evidence suggest that Legion effectiveness was severely diminished in Madagascar. And the Legion was relatively well off compared to other white units, especially the 200th Infantry, which captured the prize with 1,039 deaths.

Therefore, one might draw several conclusions from a study of these colonial campaigns of the 1890s. The first is that Legion efficiency could have been improved if French officers had paid more attention to logistics and the sanitary conditions of their troops. While the legionnaires perhaps won top prize among white troops for stamina, in the opinion of Captain F. Hellot, “had the courage of the rebels [Hovas] been as great as their mobility,” then the expedition would have been seriously embarrassed.89 The second follows on from the first, that given the generally poor quality of the enemy opposition, these imperial expeditions could have been carried out far more effectively using a greater percentage, even the exclusive use, of native infantry. The Legion no doubt provided the most solid contingent in the Dahomey campaign. They, together with the marines, certainly held the line effectively at Dogba. However, there is no evidence that native troops would not have performed well enough to thwart that attack, or that the outcome of the campaign would have been any different without Legion participation. The conquest of the Western Sudan was carried out almost exclusively by black troops. The two units that contributed most to the success of the Madagascar campaign were the Algerian tirailleurs, who emerged as the backbone of the infantry there, and the artillery, whose bombardment of the queen’s palace at Tananarive provoked the Hova surrender.

Commanders of colonial expeditions continued to request the participation of the Legion because, when properly selected and led, they made excellent soldiers. But a second important reason for the inclusion of white troops in these expeditions, at least outside of Tonkin, was not that native soldiers were skittish and lacked solidity, as was often claimed, but that their French officers did not entirely trust their native troops. Therefore, the task of legionnaires and marines was to solidify discipline within these expeditions as well as to fight the enemy. Of course, it is fair to point out that this was not an exclusively French practice, but one initiated by the British as well following the Indian Mutiny of 1857. But it was a costly task. In the final analysis, then, one must modify not only the claims of Legion historians based upon Duchesne’s praise that the Legion’s contribution to the capture of Tananarive was crucial. The old cliché might also be amended in the light of the Madagascar campaign to read, “Metropolitan troops and legionnaires go to the hospital to die. Tirailleurs just do not go to hospital.”