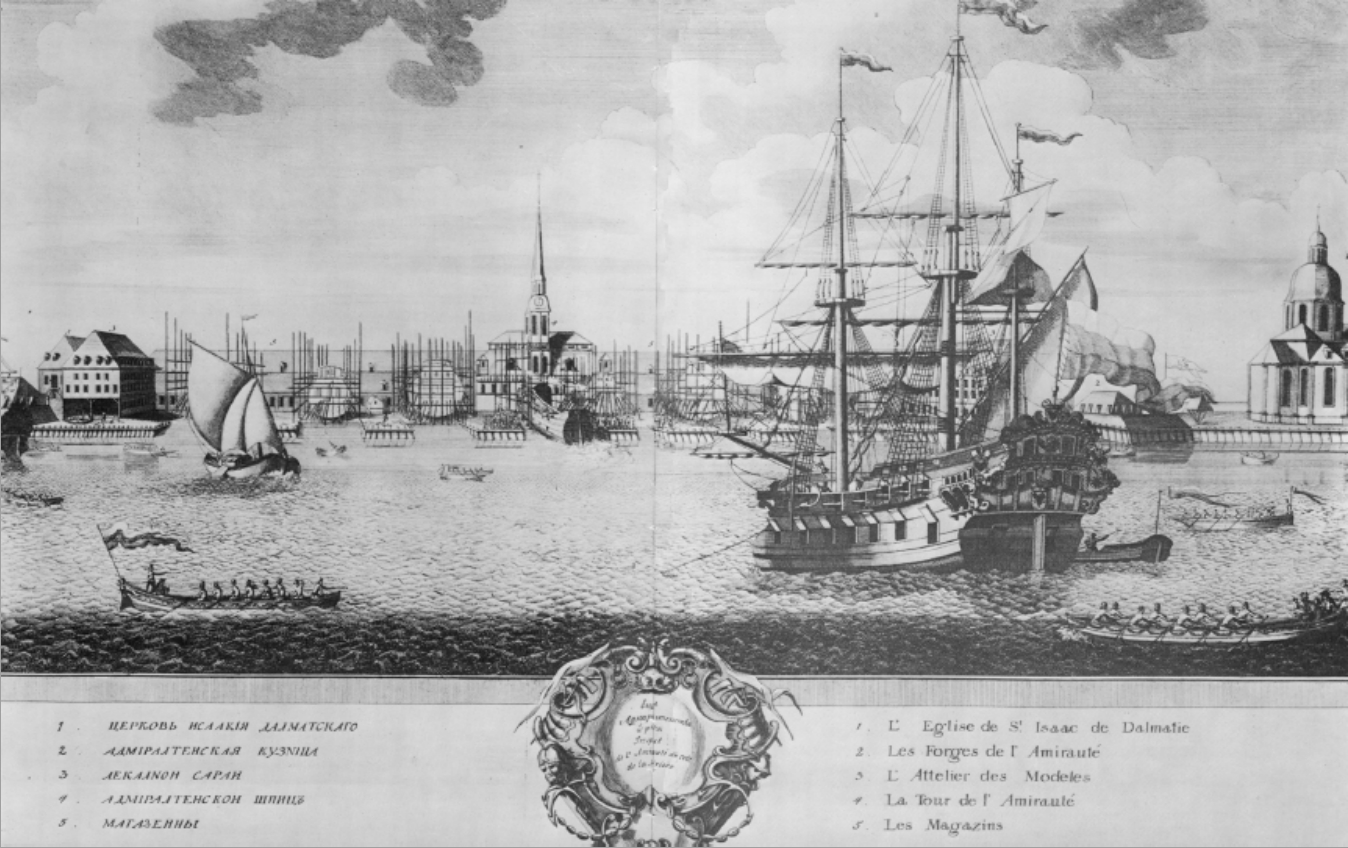

A representation of St Petersburg in 1716 by the contemporary architect Marcelius (no first initial available), showing the administrative and logistical hub of the Baltic fleet in its early years. The view is taken from the banks of the Neva looking across towards the centre of the city, with an unidentified warship anchored to the right and various small craft going about their business on the river. Visible on the opposite bank are the building slips, with a launching under way just beneath the towers of the Admiralty looming in the distance. To the right is the Church of St Isaac of Dalmatia showing the typical features of a Russian Orthodox church. The buildings scattered along the waterfront include the workshops of ship designers, the iron works (smithies) of the navy and the magazines of the fleet.

This drawing of St Petersburg in 1725 at the death of its founder Peter I should be compared with that from 1716. Both show the spire of the Admiralty dominating the skyline, but this drawing shows the impressive building from two perspectives. The cleared space in the lower picture is devoted to the drilling and housing of the Russian army and was as much a part of the underpinnings of Russian power as the fleet under construction in the upper. Both drawings show a line of battleship being launched from the slip immediately below the Admiralty tower, an indication that this artist knew of and was influenced by the 1716 representation. Details are hard to come by, but an observant eye can note that the building slips in the 1725 drawing are occupied by larger warships than those seen the 1716 drawing – a sign of the significant growth in ship size in a single decade.

Northern shipyards

Arkhangel’sk

Prior to the completion of St Petersburg on the Gulf of Finland in 1703, Russia’s major commercial seaport to the West was Arkhangel’sk at the mouth of the Dvina River on the White Sea facing the bleakness of the Arctic Circle. The shipyard servicing Arkhangel’sk was the Solombala Yard located on the Solombala islands at the mouth of the North Dvina and opened in 1693. Arkhangel’sk was never fully eclipsed by the naval hub of St Petersburg as the major production centre for the Russian sailing navy and did not finally cease operation until 1859 with the launch of the paddle frigate Solombala.

Arkhangel’sk had significant advantages as a builder of sailing warships in spite of its wretched climate and its distance from central Russia. The northern larch and pine forests provided an abundant supply of cheap timber and the extensive river network flowing into the Dvina made its transportation to the shipyards easy and cheap. Meaningful price comparisons are difficult during this period, but the cost of the larch used for a Russian 74 in 1805 was worked out at £9,000–9,500 as compared to £48,000 for the cost of properly seasoned timber for a 74 built in England at the same time. Arkhangel’sk had the additional advantage of having ready access to abundant iron ore deposits in the nearby Ural Mountains for the production of ordnance and other warship equipage. The shipyard was also sufficiently remote from the Baltic area as to be free from the likelihood of conquest by land or blockade by sea and the production of warships could continue unabated regardless of unfavourable military events to the south.

Ships completed in the northern yards were only commissioned as warships at St Petersburg after a one to two month working up voyage around the entire extent of the Scandinavian peninsula and then northwards again across the entire length of the Baltic from the straits of Denmark to the naval bases of St Petersburg. This long, arduous, and occasionally dangerous voyage gave Russian commanders a unique two-fold opportunity to work up untrained groups of landsmen with no previous experience with the sea into reasonably competent seamen and also to reveal weaknesses and defects in their newly completed warships.

There was, of course, another side to the coin. Pine and larch were not well suited for use in sailing ships, being liable to rapid dry rot and deterioration in service. The British and other European naval powers turned to the use of pine only during periods of great desperation, and ships so constructed were only expected to have useful service lives of five to seven years. The very ease of transportation of timber by floating it down the Russian waterways leading to the Solombala Yards was in itself a major accelerant to the rapid deterioration of the timber employed by saturating it with moisture at the very point in its life when it was most in need of drying out and seasoning. Floating large quantities of green, newly cut timber on water and then immediately employing it in the construction of warships was the worst possible use of ship timber irrespective of the economic advantages of the process. A one-year seasoning period was specified before the timber was used in construction, but this guideline was not always adhered to, and could not suffice to undo the damage already done. It can only be said at this point that cheapness and ease of construction had a greater priority for the Russia sailing navy than long life and durability in service. The ships produced were still effective warships during their abbreviated service lives and the wisdom of this policy must remain a matter for debate. The situation improved considerably after the accession of Nicholas I with the replacement of the waterborne transportation system by the slower and more expensive method of transportation by road and by rafting. This, in turn, had to await further emergence of Russia from a primitive medieval economic system into one more closely in step with modern European developments.

A final drawback to the use of Arkhangel’sk as a builder of sailing warships lay in the fact that completed ships could only make the long journey to St Petersburg if they were able to leave Arkhangel’sk during a one to three month window early in the season and this, in turn, might be further constricted by a late spring thaw. If the new ships missed the window for departure, they were left to deteriorate through the stresses of yet another arctic winter with increased probabilities of separation of seams and leaking when the voyage became possible in the ensuing year.

The long 2,600-mile voyage from Arkhangel’sk to St Petersburg and the exposure of untried ships early on to severe weather conditions even during summer months may have been beneficial with respect to the working up untrained crews and for uncovering defects in construction, but it was also something of a curse, with warships constructed of poorly prepared materials being subjected to unusually severe hull stresses at the very beginning of their service lives. In addition, the transit through the narrow Straits of Denmark and then along the coast of Sweden was simply not a viable option during wartime at the very time when new construction was most urgently required.

In spite of all of the drawbacks to the use of Arkhangel’sk as a construction centre, some 247 major warships were completed by the Solombala Yards between 1702 and 1855 as against the smaller total of 171 by the more strategically located Main and New Admiralty Yards at St Petersburg between 1706 and 1844 (or 202 if allowance is made to include ships built at Kronshtadt and Okhta). This total for Arkhangel’sk included 64 standard 74s, 78 66s, 21 54s and 84 frigates of all sizes. These figures, both for Arkhangel’sk and the Baltic shipyards, are of course only close approximations and subject to debate on numerous counts. Nevertheless the pattern is clear, Arkhangel’sk built more and smaller ships in all categories while St Petersburg built fewer and larger warships.

No other nation during the sailing ship era was faced with conditions approaching those imposed by this remarkable combination of poor construction materials and long transit from point of production to point of utilization. Arkhangel’sk was unique.

Bykovskaya Yard

The Bykovskaya shipyard located at Byk on the northern Dvina in the vicinity of Arkhangel’sk was the only private shipyard of significance in Russia that was contracted to build warships. Founded in 1734 by a private merchant N. S. Krylov, Bykovskaya was primarily a builder of merchant and fishing vessels but also built a small number of frigates and auxiliary vessels. The yard was finally closed in 1847.

Shipyards located in the St Petersburg Area

This section includes those yards built in and around St Petersburg including Lake Ladoga in the early years and extends to include a complex of shipyards built along the Neva River as well as the island fortress of Kronshtadt outside of St Petersburg. Some of these yards were abandoned at the end of age of sail while others continued in use, sometimes in different forms and under different names, to the present.

Syass’kaya

A short-lived shipyard built in the mouth of the Syas’ River which enters Lake Ladoga from the east. Four small frigates were built there between 1702 and 1704.

Lodeynoe Pole (Olonetskaya)

The earliest shipyard in the area, Olonetskaya, or Olonets as she was also called, was built inland on the Svir River which enters Lake Ladoga to the northeast of the future site of St Petersburg. The town serving the shipyard came to be known as Lodeynoe Pole (Boat Field) and the shipyard was known as Olonetskaya until renamed Lodeynopol’skaya Yard in 1785. Completed ships had to cross Lake Ladoga and proceed up the Neva to reach the sea. Between 1703 and 1711, Olonetskaya completed two 52-gun ships, ten snows, two bombs and various other smaller craft. Throughout the eighteenth century, the yard continued to build galleys and small craft. Between 1806 and 1820, an additional twenty additional ships were constructed there including two small frigates. The shipyard formally closed in 1849.

St Petersburg Main Admiralty Yards

The site of the new Russian capital of St Petersburg in 1703 was chosen by Peter I with an eye on its strategic positioning at the head of the Gulf of Finland, with its excellent defensive potentialities and its potential for controlling the entire Baltic to the south. The naval shipyards on the Neva River had access to Russian river waterways for the transportation of timber from the interior comparable to that of the Arkhangel’sk shipyards along with the added advantage of readily available supplies of high quality Kazan’ oak along with abundant supplies of larch. Fewer warships were completed in the shipyards around St Petersburg than those at Arkhangel’sk, but St Petersburg was entrusted with the honour of constructing the great majority of the Baltic fleet’s prestigious First and Second Rates as well as the more important of the heavy frigates. It seems likely that this division of labour between the two yards was a result of the greater durability and life spans that could be hoped for from ships built of higher quality timber than was available to the northern yard, especially when spared the trials of the long transit from Arkhangel’sk.

St Petersburg was very nearly as long-lived as its northern compatriot and rival, with the main admiralty yards continuing to build major sailing warships for the Russian Navy from their founding in 1706 to 1844. The total production of both the St Petersburg Main Admiralty and New Admiralty yards taken together (but excluding Okhta and Kronshtadt) was 21 100-gun ships, 30 80-gun ships, 20 70-gun ships, 33 64/66-gun ships, 14 52-gun ships and 53 frigates of all categories.

Galley Yard

Located slightly downriver from the Main Admiralty Yards, the Galley Yard was primarily involved in the production of galleys and other oared craft until it converted to the New Admiralty Yard in 1800 (see below).

Galernyy Island Yards

This site is referred to as Galernyy Ostrovok (Gallerny Island in Russian) throughout the data section. The site was founded in 1719 and built small galleys and sailing ships including 50 Crimean War gunboats, before beginning to construct larger craft from 1858. It was merged with the New Admiralty Yards in 1908.

Two plans of the naval base of Kronshtadt completed on Kotlin Island in 1713. The top view depicts the base in 1721 as planned by Peter I. The lower shows the changes made by 1741–3. Both reveal the heavy fortifications that guaranteed its dual status as both the guardian of the Russian capital at St Petersburg and as the major naval base for the Baltic fleet. No serious assault on St Petersburg would have been possible without first reducing this fortress, and the guns of Kronshtadt retained their deterrent value throughout the course of the Napoleonic Wars – and long after.

Kronshtadt

The main naval base for the Russian Baltic fleet was created in 1713 located on the Kotlin Island protecting the approaches to St Petersburg. Both a fortress and a naval base, Kronshtadt was primarily involved with major repairs. Construction activity was largely limited to important larger ships and to specialized prototypes because of the difficulty involved in transporting quantities of timber to the island. With the lonely exception of Sviatoi Pavel 86 of 1753, the production of major warships at Kronshtadt began in 1771 with the laying down of the 10-gun bomb Iupiter and continued through 1813 with the launching of the 100-gun Rostislav. Twenty-two warships ranging in size from First Rates to cutters were constructed there between 1753 and 1813 including four First Rates, one 80, one 66, eight rowing frigates and eight smaller ships.

With the great dry dock facility begun at the order of Peter I and completed in 1752, along with its vast complex of workshops, Kronshtadt has remained the main arsenal, repair and maintenance base for the Russian Baltic fleet to the present day. In 1857 it was determined that Kronshtadt was no longer suitably placed to act as an operational centre for offensive fleet operations. Plans were accordingly made to move fleet operations and the Admiralty headquarters to Rogervik, while retaining Kronshtadt as the armoury and repair centre of the Baltic fleet. Although financial constraints prevented the fulfilment of this project, the harbours serving Kronshtadt were deepened over several years beginning in 1859. A second attempt at providing a more forward operating base for the fleet was undertaken in the 1880s at Libava (now Lithuanian Liepaia), but these were abandoned in their turn in favour of Revel’ in 1912.

Okhta Yards

Also known as Okhtenskaya, this yard was located on the Okhta River, a branch of the Neva in the vicinity of St Petersburg. Builder of small vessels between 1781 and 1794. Between 1810 and 1862, Okhta became a major shipyard, completing eight 74s, nine heavy frigates and 49 smaller ships.

New Admiralty

The New Admiralty yards in St Petersburg were built on the Neva on the site of the former Galley Yard in the final year of the Emperor Paul’s short and tragic reign in 1800; 25 major sailing warships were built there between 1806 and 1866, including two First Rates, one completed as a steamship, twelve 80-gun ships, four 74s and three 44-gun heavy frigates. An additional four wooden screw and paddle cruising ships were also completed there between 1844 and 1866. New Admiralty continued to produce iron and steel hulled warships until 1908 when it merged with the Galernyy Island yard.