Pirates often sailed vessels other than ships. For example, the dugout canoe was one of the most common of pirate vessels. In the late seventeenth century, buccaneers and filibusters used them for raids up rivers on the Spanish Main, towed them astern or carried them aboard their larger vessels, and often began their piratical careers aboard them, working their way up from canoe to small merchant bark to barcalonga, tarteen, or sloop, and finally—sometimes—to frigate, small or large, the smaller vessel capturing the larger. And sometimes they fought barks and small ships with canoes, as the buccaneers at Perico did. Sometimes they even fought great ships, such as the four- or five-hundred-ton “hulk” of the Honduras urca, a large-bellied flat-bottomed cargo carrier. Famous cutthroat pirate François l’Ollonois captured a hulk this way.

In the late seventeenth century, the barque longue, or in Spanish, barcalonga, the common bark, and the sloop were the most common vessels among the pirates of the Caribbean. A barque longue was a long, narrow, open-decked vessel with shallow draft. It carried one or two masts and one or two sails, although some carried topsails as well. The sails of Spanish barcalongas, and perhaps those of some of the French barque longues, were lugsails that could be easily changed from side to side for tacking. The best pirate craft were those that could escape to windward (toward the wind). Pirate craft in the Caribbean also needed to be able to sail against the prevailing trade winds, and the lugsail made this easier.

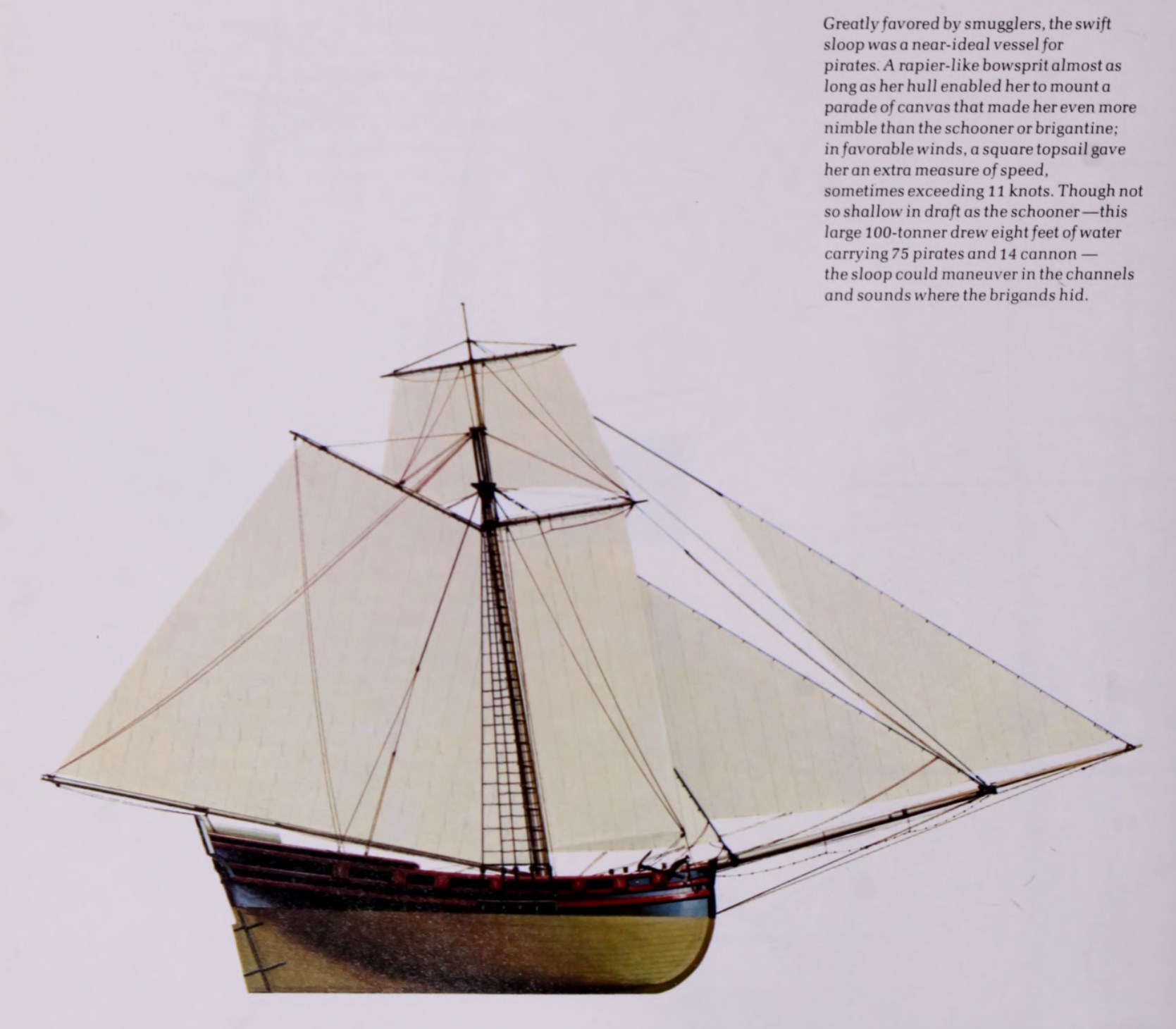

However, the sloop deserves the most fame as a pirate vessel, especially the sort called “Bermuda,” named for its place of construction, although in fact it had originated in Jamaica. Sloop builders shifted to Bermuda after the timber ran out in Jamaica. These sloops were swift vessels, built of cedar, with hulls well tallowed and chalked for speed, fore and aft rigged with an enormous mainsail, and in the eighteenth century, with a tall single mast raked strikingly aft and a long bowsprit thrust piercingly forward like a Spanish rapier. You could not miss recognizing one, even at a distance. As Jamaica sloops they were popular in the second half of the seventeenth century, and as Bermuda sloops grew even more so in the eighteenth. There are only a few significant pirates who never sailed a Jamaica or Bermuda sloop at one time or another.

By chance, we have an outstandingly detailed description of a pirate sloop, whose short story is in itself a fascinating one. In early 1718, Captain Charles Pinkethman set sail from Jamaica aboard the sloop Nathaniel & Charles, intending to make his fortune upon the Spanish treasure wrecks in the Bahamas. Unfortunately, his dreams of salvaged silver were short-lived. He died en route, leaving the sloop’s master, suitably named Tempest, to take his place. At Walker’s Cay, in the Abaco Islands of the Bahamas, they put their African or Native American divers to work, but to little profit. Weighing their anchor, they sailed with another sloop to Bimini and worked a wreck there, but it, too, held little profit.

A mutinous sort named Greenway commanded the consort sloop. Failing at treasure hunting, he had sniffed the air and caught the whiff of piracy. Bad fortune had discouraged Tempest’s crew, leaving them vulnerable to the temptation of piracy, now beginning to flourish in the Caribbean and Americas. Greenway lured them with golden dreams, assuring them that piracy was far more profitable than hunting for treasure on sunken wrecks.

Under the influence of Greenway, Tempest’s crew mutinied, “took possession of this sloop and all the arms, and threatened to shoot Captain Tempest and all that would not go with them under Greenway’s command.” Yet in spite of the threats, Tempest and more than a dozen steadfast seamen refused to join the pirates. Relenting eventually, the pirates transferred some of them to another sloop and let them go. But they didn’t release all the seamen. The new pirates forced several to remain behind.

West now the sloop sailed, to Florida to fish for silver—a curious way to begin a pirate cruise that was instigated by failing at fishing for silver—but Spaniards on the shore welcomed them with volleys of lead. Sailing north, Greenway brought his sloop into an inlet south of Charlestown, South Carolina, and fitted her with a new mast. At sea again, they captured and released a small sloop, ran from a twenty-four-gun French merchantman, and sighted the Spanish treasure fleet but ran when they realized a Spanish man-of-war was lying in wait for them. So much for “plucking a crow” with Spanish galleons! Near Bermuda, they captured two sloops, kept one, and forced a few men to join the pirate crew.

Pirates of the early eighteenth century often forced freemen, seamen, and fishermen to join their crews, unlike the late seventeenth-century buccaneers and filibusters, who forced only slaves and the occasional Spanish pilot. Thirteen of these forced men wanted to be rid of their captors. All they needed was an opportunity; a chance to maroon themselves ashore would be ideal. But they got better than they could wish for.

On July 17, 1718, the pirates sighted and gave chase to a ship. Ranging up close, the pirates hoisted their black flag, fired a cannon and, for emphasis, a volley of muskets at the ship. Immediately, the merchantman lowered her topsails, lay by in the trough of the sea, and waited to be boarded. Captain Greenway, greedy as ever, clambered into the sloop’s boat, along with his gunner, doctor, and a few other officers, leaving the pirate crew and forced men behind.

Suddenly, the wind filled the ship’s sails, which were balanced against each other as she lay by, and pushed the ship down upon the sloop, smashing into her quarter. But rather than worry about the accident, the pirate crew leaped aboard the ship, rabidly looking for plunder. It was every man for himself. They ran about the ship, pillaging as they could and paying no attention to the sloop they had just left nor to their captain. After all, pirate captains had absolute authority only in battle. Just a few pirates were left aboard the sloop.

The forced men seized the moment. Richard Appleton, one of the few to be armed, took the helm and ordered John Robeson below to secure the stores. He shouted to the black men aboard—slaves probably, but possibly freemen, perhaps even divers—to hoist the sails. Immediately, a pirate realized what was happening. He seized a musket, aimed it at Appleton, and “snapped it,” as pulling the trigger was known due to the sound of the flint striking steel.36 But it misfired, and again so.

Swiftly, he reversed it in his hands and swung the butt at Appleton, cracking it over his head. Appleton went down. But the black men aboard had no more reason to want to be with the pirates than the forced white men did. One of them shot the pirate in the belly with a pistol, and another shot him in the leg. Quickly they trussed up the pirate and seven of his fellows, all of whom were mostly drunk, put them all in a canoe, and set them adrift. To Philadelphia the pirate prisoners—the “forced men” from Tempest’s crew—and their black comrades sailed and gave themselves up, where all—at least the white seamen—were “well used and civilly entreated for the service they had done.”

Thankfully, the council at Philadelphia kept a detailed inventory of the sloop, probably the most detailed we have of a pirate craft of the Golden Age. She had a full set of sails, including a jib, a flying jib, and a spritsail, plus three anchors, and tools, lumber, tar, and other sundries for making repairs. For navigation, she had three compasses; for maneuvering in calm or light airs, a set of oars or sweeps; for feeding her pirate crew, thirteen half barrels of beef and pork; for cooking, a kettle and two iron pots; for treating her sick and wounded, a doctor’s chest; for tricking the prey, a pair of false colors and pennants, and a jack; and for intimidating the prey, a black pirate flag and a red “no quarter” flag.

More important to her purpose, she mounted ten cannon of small caliber, along with two small “swivel guns” that loaded from the muzzle, and nine patereros (a form of small swivel cannon) that loaded from the breech. But six of the patereros were old and may have been unserviceable. She also had ten “organ” barrels belonging to a small bit of rail-mounted artillery known as an organ: a sheaf of musket barrels made to fire together, more accurate than a common swivel.

The sloop also carried two hundred round shot for her cannon, which is really not all that many, four kegs of scrap metal for loading in canvas bags and firing in a murderous hail at men, and thirty-two barrels of gunpowder. She carried fifty-three grenades, vital for boarding a ship under fire, and thirty muskets, just as vital for attacking a ship. Muskets were used to suppress enemy fire and often made the difference even when ships were fighting with their great guns broadside to broadside. In fact, the musket was the principal weapon of the pirate.

Sloops like this were the most common seagoing pirate vessels of the Golden Age, and the ones we should most associate with pirates. Certainly the most common was not the galleon, which by the eighteenth century no longer really existed except in name; only a handful of real galleons, known by the design of their hulls, still sailed. Even so, many pirates did sail ships and other three-mast vessels. Most were small frigates, usually of only one or two hundred tons and of ten to twenty guns of two- to six-pound caliber, often with as many swivel cannon mounted on the rails. But some pirates captured large merchantmen or slave ships, converted them to pirate ships, and sailed the seas with ships of forty or even fifty guns. These ships were often slow compared to their prey, or at least no swifter, and slow compared to pirate hunters. Further, they were expensive to maintain and required a lot of maintenance—and pirates were generally a lazy lot.41 Most of the time, pirates preferred lighter, swifter vessels—fast enough to overtake prey and run from a pirate hunter and armed well enough to make a stout fight if it came to that. Often large pirate ships were accompanied by light, swift craft, as we have already seen in the case of Blackbeard’s pirate flotilla.