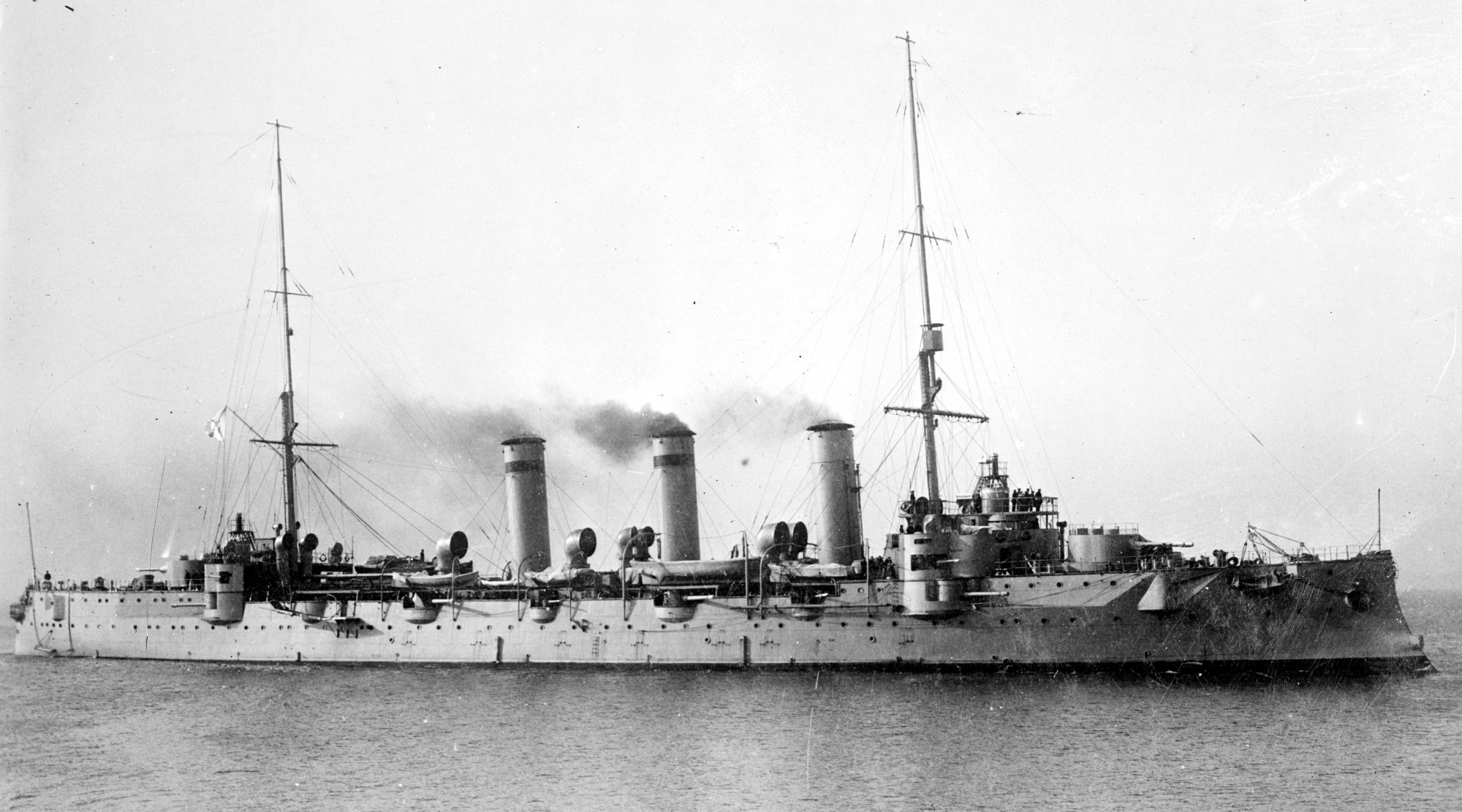

The Bolshevik cruiser ‘Oleg’

In February 1919, a slim, pale naval officer was escorted into a building in Horse Guards. When he came out again, he had joined the intelligence service.

Twenty-nine-year-old Lieutenant Augustus Willington Shelton Agar RN was descended from a long line of Kerrymen. Born in Kandy, Ceylon (Sri Lanka), the thirteenth child of a planter from County Kerry, John Shelton Agar, he was an orphan by the age of twelve, losing his mother one year after his birth and his father in 1902, killed in a cholera epidemic in China.

Educated at Eastman’s Naval Academy and HMS Britannia, he passed out as a midshipman in 1905. Agar gained a pilot’s certificate in 1913, unusual for a naval officer in those times, and served with the Grand Fleet in the North Sea during 1914–15, before taking part in the evacuation of Gallipoli. Further service in the White Sea followed from whence he was transferred, initially as a torpedo and mining officer, to a top secret Coastal Motor Boat (CMB) base on Osea Island, in the estuary of the River Blackwater in Essex. Here he saw action with the Harwich Force and in Operation ‘ZO’, the attack on Zeebrugge and Ostend (an action which was entirely ‘volunteers only’), where Agar commanded a smoke-laying CMB.

Agar had not been considered by his previous commanders as a particularly competent officer. In mid-1913, his captain evaluated him as being ‘capable when he tries but at times shows lack of interest’. By mid-1916, he was thought to be ‘clever but unreliable; apt to do foolish things; deaf one ear’. Six months later the same commander again noted that Agar was ‘clever but unreliable’. And in early 1918, a Lieutenant Commander Parker wrote that he was ‘hardworking, at times spasmodic, not tactful, violent temper, conceited but good knowledge at bottom’. Hardly ‘officer-like qualities’; but in the freewheeling world of CMBs, Agar had at last found his metier.

CMBs, popularly known as ‘Skimmers’, were first developed by the Thornycroft company in the summer of 1915. Shortly afterwards, three lieutenants§ of the Harwich Force approached the company and stated that their commodore (Reginald ‘Black Jack’ Tyrwhitt) had given them permission to speak to the management and ascertain if the boats had a role in warfare. The idea developed by these officers was that a very fast, shallow-draught vessel would be ideal for attacking German ships in their harbours. It would be able to pass over the defensive minefields without triggering one and its high speed would allow rapid strike and escape.

Introduced in 1917, the boats made use of the lightweight and powerful petrol engines becoming available and a variety of armament was carried, including torpedoes, depth charges or mines, together with light machine guns, such as the Lewis gun. They were of monocoque construction with a ‘skin’ of Honduran mahogany backed by oil-soaked calico which ‘fed’ oil to the wood over time to prevent it drying out.

They were initially propelled by 250 brake horsepower V-12 aircraft engines made by Sunbeam and Napier and later used engines of Green’s and Thorneycroft’s own manufacture. This made them very fast (they could hit 40 knots and average 35) and able to skim over the top of minefields by aquaplaning. CMBs were the navy’s equivalent of fighter aircraft and were manned by young and adventurous men (usually a crew of three or four), as were their aerial equivalents. They were dangerous and difficult to handle; but they were also beautiful to look at. One naval officer wrote ‘I do not know who invented the CMB but this little vessel was a masterpiece of ingenuity, so much so that I wept with envy when I saw the first one go over from Dover to Dunkirk’.

CMB commanders, like their alter egos in the air, were seen (and often saw themselves) in Arthurian terms. The dominant moral codes of the late Victorians and Edwardians were derived from their reverence for the chivalric, the lost Eden of Arthurian legend, Camelot, the Round Table and from their obsession with England as a new Rome. The educational system was founded on the classics for that very reason. Thus public schools and colleges produced a breed of men who were devoid of guile and conditioned to believe in romantic notions of honour, glory and sacrifice. These educational establishments raised boys to believe in chivalric values that were all the more potent because they had not been tested in the real world. And as one historian has written, ‘every public schoolboy was familiar with the Iliad and the Odyssey and the poetry – with its emphasis on honour, discipline, athleticism and courage in the face of death – spoke across the ages about what it meant to be a gentleman and a scholar at the height of empire’. They were the modern-day knights errant and CMBs were their chargers.

Nonetheless, service in CMBs was not without its problems. For example, their petrol-powered engines were prone to catching fire (during the year 1917–18, five CMBs were lost through fire, three of them whilst still in harbour); and the restriction on weight necessary to obtain the high speed and low draught, meant the torpedo could not be fired from a normal torpedo tube but was instead carried in a rear-facing trough. On launching, it was pushed backwards by a cordite firing pistol and a steel ram and entered the water tail-first. A tripwire between the torpedo and the ram head would start the torpedo motors once pulled tight after release. The CMB would then turn hard over and get out of the way. Clearly this was an operation fraught with danger – but there is no record of a CMB ever torpedoing itself.

Nor were they comfortable. They carried a commanding officer, a second-in-command, who also functioned as observer, and one or two engineers who sat crouched under the deck in front of the two officers. This position was particularly exposed and uncomfortable, perched beside their machinery whilst all the water breaking over the bows fell on them; they had to sit chin on knees, doubled up, managing the temperamental petrol engines.

With the war over, Agar had resigned himself to a long and boring period of relative inactivity; at the armistice ‘all thoughts of the Big Attack had of course to be abandoned’, he fretted. He and the other officers continued to work on Osea Island, ‘keeping our boats and base up to concert pitch’. They found it difficult work as ‘many of the Hostilities Only young seamen and mechanics were longing to be demobilised and sent back to their homes’.

But then, whilst on leave in London, he was contacted by his commander at Osea, Captain Wilfred Frankland ‘Froggie’ French, and told to report to the Admiralty for an important meeting. From there he was conducted to Horse Guards; and inside he met ‘C’, the legendary Mansfield George Smith Cumming, head of Britain’s Secret Intelligence Service. Cumming was running agents in Russia; but the flow of information had ceased and his normal couriers had been either killed or imprisoned. He needed to be able to get agents and messages in and out of Russia, especially Petrograd, and a CMB, able to pass over the defensive minefields and travel quickly and stealthily, seemed the ideal vehicle.

Agar was given £1,000, told to pick his own crews and furnished with two CMBs. His orders instructed him to make his own way to Finland in secret and set up base there. Once there and united with his boats and their crews, Agar planned to establish his operations at a derelict yacht club at Terrioki, 30 miles north of Biorko and just three miles from the Finnish/Russian border. He had selected five men he knew from Osea Island; two sub lieutenants, Edgar Robert ‘Sinbad’ Sindall and John White Hampsheir together with Midshipman Richard Nigel Onslow Marshall, all reservists RNR, and two Chief Motor Mechanics, Hugh Beeley (an RNVR member, Rolls-Royce trained and known as ‘Faithful Beeley’) and Albert Victor Piper. All the men had volunteered for this special service

Agar had been instructed to contact Cowan for assistance and did so, requesting a destroyer to tow his little vessels to his new base and the admiral so ordered Voyager on 4 June, telling Captain ‘D’ that it was for ‘running our spies to a place well up the coast’. Agar also asked Cowan for two torpedoes; as Agar himself put it, ‘I had been told to avoid all operations which could involve us in a hostile act, as our boats were supposed to be civilian in character, yet these torpedoes might come in very useful in self-defence if we found ourselves up against Russian ships’. Cowan firstly ordered Lieutenant Commander Willis to see Captain ‘S’ about putting ‘four [18in] Mark VIII torpedoes for the CMBs on board Voyager’. But at some point he must have had cold feet for Agar found him unwilling; ‘the thought of men in civilian clothes using weapons … did not appeal to him’. But Agar pointed out that ‘C’ had given them permission to take one set of naval uniforms with them and promised that, if he did have to engage an enemy, he would ensure they wore their uniforms and flew the White Ensign.

It suited Cowan’s warlike nature to allow Agar his torpedoes; but he wanted no responsibility for the act. Instead he said that he would order a small oiler to be available with petrol and oil for the CMBs, adding that ‘it might be carrying on its deck two torpedoes for our submarines’. Later, when they were alongside the oiler, Agar discovered that there were two long objects under canvas on its decks. He recalled afterwards that ‘the master of the oiler told me that he had picked them up floating at sea and I could have them as they were not on his charge’. Agar had got his torpedoes.

However, the first problem to overcome was an engine failure in one of the boats. Agar and his team had to rig sheer legs to hoist the engine out and repair it. But by 10 June, both vessels had been tested and were ready for work. The destroyer HMS Voyager towed them out of harbour and they set course for their new base.

Agar’s assigned task was to deliver into Russia a courier, codenamed ‘Peter’, who would make contact with one of Cumming’s key operatives inside the country, designated only as ‘ST 25’ but in reality the accomplished espionage agent Paul Dukes. Agar was then to bring either both agent and courier, or ‘Peter’ only, out again.

While Agar was preparing to depart his new home with ‘Peter’, he gained information which would have a key part to play in the events of the coming few days. The small Royal Navy team shared their yacht club with a detachment of Finnish border guards whose commandant had been encouraged to accept them and ‘look the other way’. He now told Agar that on 10 June the garrison at the fortress of Krasnaya Gorka, which guarded the southern entrance to Kronstadt, had revolted, arrested their commissars and hoisted a white flag as a signal to White Russian and Allied forces to come and rescue them. The commandant was sure that the Bolsheviks would send a force to recapture the strongpoint and use warships to bombard it from the rear.

But Agar’s first priority was to deliver ‘Peter’. A local smuggler had been hired to act as a pilot and, taking Beeley with him, they departed Terrioki after dusk on 13 June in CMB-7 and headed for Russian soil. On the open sea they increased speed to 20 knots until the fortress of Kronstadt came into sight and then throttled back. At 8 knots the boat was practically silent and Agar aimed for a gap between the sixth and seventh forts in the line of defences, expecting at any moment to be illuminated in a searchlight beam and fired upon. The minefields were laid at a depth of 6ft so were harmless to a CMB but the breakwaters were believed to be only three feet below the surface, giving his boats a mere 3in clearance. It would be a risky endeavour to cross between the forts and over these hazards.

Miraculously they made it through to the other side of the line. The sunken breakwaters proved no hazard and, free of the defensive line, Agar called for top speed; at 36 knots they sped towards land. ‘Peter’ was successfully landed in Russia, within walking distance of Petrograd.

Now Agar headed towards the Tolbuhin Lighthouse so that he could observe any vessels drawn up to bombard the rear of Krasnaya Gorka. Sure enough, he could distinguish two heavy ships, which he identified as Petropavlosk and Andrei Pervozvanni, and a number of shielding destroyers. They had left the sanctuary of their harbour and were standing out in the roads, admittedly covered by the protective minefields and the guns on Kronstadt itself, but still out in the open – but these defences rendered Cowan impotent to intervene with his warships. In his subsequent report, Agar stated that he thought of attacking the Red ships there and then, but his engine malfunctioned, rendering him unable to attain sufficient speed for a torpedo launch. Instead CMB-7 returned to base.

Agar had agreed to return to the drop-off point in forty-eight hours’ time to effect a pick-up rendezvous. While he waited, he was able to see the Red ships bombard the unfortunate fort at regular intervals. The would-be warrior was disturbed; ‘I was tempted at first … to attack those battleships with the torpedoes we carried in our boats. But I soon gave this up, as our duty to ST 25 must come first’, he wrote. A knight has a responsibility to help those weaker than himself; but Agar had conflicting priorities.

Then, on the 14th, Agar observed a strange little vignette which also saw the Estonian navy gain another vessel. During the gunfire from the fort, he spotted a small Russian gunboat, the Kitoboi, emerge from the environs of Krasnaya Gorka flying a large white flag. She approached HMS L-12, which was on patrol in the area, and Lieutenant Blacklock, exercising considerable caution, launched a boat and sent an officer across to ascertain what the Russian wanted. It transpired that the crew, unimpressed by the Bolshevik regime, had mutinied and forced their captain at gunpoint to sail out and surrender to the Royal Navy. Seeing no alternative, the Russian had complied but told L-12’s officer, with tears rolling down his cheeks, that the result would be that the Bolsheviks would slaughter his wife and family. Nonetheless, Blacklock escorted the gunboat out of the area and then turned her over to a destroyer. Cowan presented her to Pitka. The Russian captain immediately joined the White army but, Lieutenant Blacklock was later informed, was captured and crucified by the Reds.

The gunboat crewmen were perhaps encouraged in their actions by a radio broadcast made by Cowan on 6 June, in which he had invited the ships in Kronstadt to leave their base, raise a white flag and surrender. Perhaps unsurprisingly, they declined, with the single exception of the Kitoboi. The Bolshevik command replied ‘asking if we were not tired of war after five years of it and why we “could not mind out own business”’. Nonetheless, Kronstadt was allocated a call sign and told to use the 800-metre band if they changed their mind.

Coastal Motor Boat (CMB 4) The first twelve 40-foot Coastal Motor Boats (CMBs) were ordered by the Admiralty from J I Thornycroft’s in January 1916, and by August were delivered. They were armed with one 18-inch torpedo and Lewis guns, and could make well over 30 knots. CMB 4 was one of this batch. CMB 4 had a most distinguished career. Initially she was based at Dunkirk, operating as part of the Dover Patrol, and taking part in raids on Ostend and Zeebrugge, including the famous Zeebrugge Raid of 23rd April, 1918. In 1919 CMB 4, commanded by Lieutenant Augustus Agar, was used on Secret Service operations in the Baltic. In June Agar and CMB 4 sank the Bolshevik cruiser ‘Oleg’. Agar was awarded the VC. In August Agar and CMB 4, with other CMBs participated in Operation RK, the famous attack on Kronstadt Harbour. Two VCs were awarded and Agar received the DSO. CMB 4 was exhibited at the Motor Boat Exhibition at Olympia in 1920 and subsequently at the IWM/Crystal Palace.

‘Peter’ was duly collected, without Dukes who had decided to stay on and collect more intelligence, and thus Agar’s immediate mission was completed. He was now without tasking, until further instructions arrived from Cumming in London.

A lack of orders did not deter Agar; he knew that he was both in a position to take some offensive action and equipped to do so. He also surmised that the Krasnaya Gorka garrison could not hold out for much longer in the face of continued bombardment. Agar resolved that he would act. But first he would seek authority to do so. Via an agent of SIS based locally, Agar sent a coded message to Cumming asking for permission to attack. The reply came back ‘Boats to be used for intelligence purposes only, take no action unless specifically directed by SNO Baltic’. This response did give some ‘wriggle room’ in its second phrase. There was, in any case, no time to seek Cowan’s endorsement if he was to seize the moment; but Agar felt confident, given the Admiral’s reputation, that Cowan would support him. ‘I was quite certain in my mind,’ he wrote, ‘what his [Cowan’s] wishes would be and decided to attack the Red ships that very night.’

On Monday 16 June, Lieutenant Agar left his base at 2215 hours (Finnish time) and set course for Kronstadt with both CMBs; CMB-7, now commanded by Sindall and Agar himself in CMB-4. From courtesy, Agar had sent a message to Cowan giving his intentions. He and his men had their naval uniforms with them and both boats were flying small White Ensigns.

The plan was to again pass through the Russian defences and attack the ships now in the roads with torpedoes, at around midnight. But disaster struck. While rounding Tolbuhin Light, CMB-7 struck a submerged obstacle, probably a ‘dud’ mine, which broke her propeller shaft. Marshall, although a non-swimmer, went over the side to see if he could fix the problem, to no avail. Agar took her in tow and they returned to Terrioki. Sindall’s mechanic, Piper, immediately dived overboard to examine the shaft, but surfaced with a look on his face which required no further explanation. The shaft was beyond repair; and they had no spares.

From a lookout point in a nearby church steeple, Agar was able to observe that the two battleships seen earlier now had steam up and were under way, back to harbour. In their place had arrived a large cruiser, the Oleg; the destroyers were still in position. That afternoon, the cruiser restarted the bombardment of the fortress. It was now or never. The fortress needed help; there was a target of opportunity in the roads; and he still had one CMB. Lieutenant Agar determined to attack that night, the 17th.

Hampsheir, Beeley and Agar once more put on their uniforms and mounted their charger. At 2230 local time, CMB-4 slipped out of harbour. They were off to challenge the Russians to single combat. The weather was worsening with a heavy swell, not ideal conditions for a small 40ft-long motor boat, but they reached the position of the cruiser around midnight. She was protected by a destroyer screen and the first task was to slip through it unobserved.

To ready the torpedo for launch, Agar ordered Hampsheir to remove the safety pin from the cartridge in the firing chamber. There was a sudden noise, the boat shook and Hampsheir reappeared with an agonised look. While trying to remove the safety pin from the firing pistol lanyard, it broke, leaving the pin still in. As Hampsheir fought with the device, the pin suddenly came out and the pistol fired. Fortunately, the linkage to the explosive firing charge was also faulty and the torpedo launching mechanism itself did not fire.

They now had to stop the boat and reload the cartridge, difficult on land, even more so when the vessel was rolling in a sea. Beeley took over and removed the starting pistol and replaced the cartridge. At 2350 it was ready to use. The whole process had taken fifteen minutes, all the while with Russian destroyers 200–300 yards to either side of them and the big cruiser in silhouette ahead. As Agar wrote later ‘I, of course, dared not leave the wheel and controls. I could see the black hulls of the destroyers and waited for gun flashes. We were a “dead sitter” but, luckily for us, remained unseen.’

When Hampsheir finally popped up the hatch to say all was well, Agar slipped the clutch and went to full speed. The little craft tore down on the cruiser. Holding on until the range was 500 yards, he fired the torpedo and turned almost a complete circle, now heading back the way they had come, followed by the wind and, more worryingly, the first gunfire.

The torpedo hit abreast the foremost funnel and a huge column of black smoke rose up from the stricken ship. Both forts and destroyers opened fire on them, fortunately going high, and they gave three cheers for themselves, unheard above the engine’s roar, as they fled away. Shells exploded in the sea around them, soaking the men and their craft but none stuck home. At 0300 they reentered Terrioki; Agar and his crew had just sunk a large Russian armoured cruiser of twelve 6in guns, 576 men and 6,975 tons.

The wait to reload the torpedo cartridge had been nerve-wracking and only Beeley’s steadiness had got the job done; as Agar said, ‘no fuss, no worry, Faithful Beeley indeed’. But reality had intruded into the Arthurian world. Hampsheir’s nerves had not been up to it. ‘He was in a poor way, principally from shock’ and would not, in fact, recover; Agar had to send him to a sanatorium in Helsingfors, where a nervous breakdown was diagnosed and he was cared for by an English matron.

By borrowed car, and then on horseback, Agar set off to find Cowan, locating a boat from HMS Dragon instead and, after a problem convincing them who he was, he gained permission to await Cowan’s arrival with her. At midnight, the flagship arrived and Agar rowed himself across. Cowan received him, despite the hour, and sat up in bed in his sleeping cabin while Agar told his tale. Cowan was pleased. ‘This allows me to show them that I have a sting which I can always use if they show their noses out of Kronstadt,’ he declared and the admiral told Agar that he approved of his action and would defend him if the Foreign Office played rough. Sinking Oleg was not enough to save the Krasnaya Gorka fortress, however. The next day, red flags were once more flying over it.

Anxious to hide the exact nature of the secret weapon that he possessed, Cowan wrote to all his commanders that the Bolshevik cruiser Oleg had been sunk at Kronstadt on the night of 17 June by Lieutenant Agar in a CMB but that he was anxious that the methods of sinking should not become known on the shores of the Baltic. But when Agar brought his CMBs back to Biorko for repairs, one towing the other, Cowan formed up his fleet in two lines; as the little boats passed through them, each and every warship ‘manned ship’ and cheered them through.

There was even a little rejoicing in Parliament. On 13 August, in what was obviously a ‘planted’ question given both were members of the government, Lord Curzon asked Walter Long ‘if he is in a position to give any particulars as to the sinking of the Bolshevist’s [sic] cruiser?’ Long replied that ‘the Bolshevist cruiser Oleg was sunk by British naval forces which encountered her when patrolling. It is obviously undesirable to give the exact means by which this was accomplished.’ Cowan’s wish for anonymity of method was respected. And the ever-persistent Lieutenant Commander Kenworthy chipped in with a follow-up question. ‘When will dispatches be published showing the excellent work of the Royal Navy in the Baltic since the Armistice?’ Financial Secretary to the Navy, Dr Thomas James Macnamara swatted that one away. ‘I do not think I can answer that. There are a great many difficulties which I cannot at present measure. I quite agree it is desirable that the splendid work done should be known.’

For his bravery in action, and on Cowan’s recommendation, dated 26 August, Lieutenant Augustus Agar was awarded the Victoria Cross. Because of the secret role he had been engaged on, and his ‘unofficial’ presence in the Baltic, the citation for the award merely stated that it was ‘in recognition of his conspicuous gallantry, coolness and skill under extremely difficult conditions in action’, for which reason it became known as ‘the mystery VC’. Chief Motor Mechanic Hugh Beeley RNVR, twenty-four years old, was also recognised with the bestowal of the Conspicuous Gallantry Medal, with the same citation given as for his commander. He also received a £10 per annum gratuity in recognition of ‘his management of the engine of an obsolete type of motor boat which failed during a previous attempt’. And 21-year-old Sub Lieutenant John White Hampsheir RNR gained the DSC.