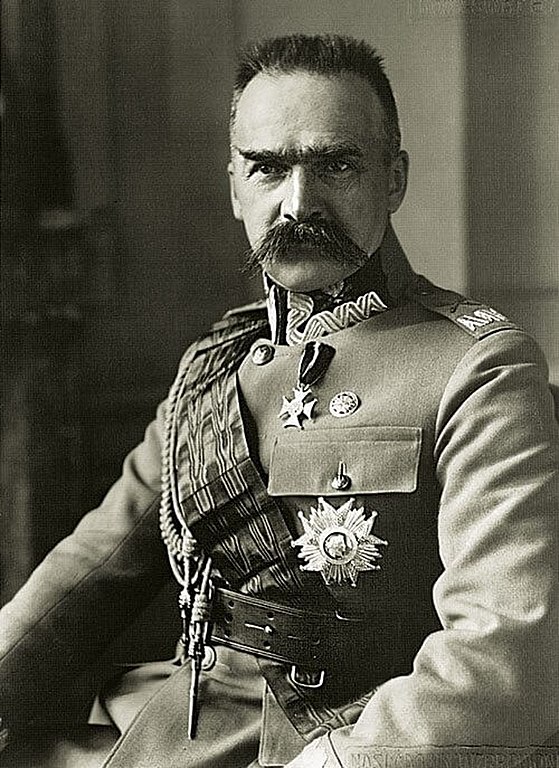

Józef Piłsudski, Chief of State (Naczelnik Państwa) between November 1918 and December 1922

1920 Map of Poland

‘An independent Polish state should be erected which should include the territories inhabited by indisputably Polish populations, which should be assured a free and secure access to the sea, and whose political and economic independence and territorial integrity should be guaranteed by international covenant.’

President Woodrow Wilson’s Fourteen Points, 8 January 1918

The resurrection of Poland simultaneously occurred on both a military and a political dimension, driven in large part by two charismatic revolutionaries. In the military realm, Józef Piłsudski, scion of a wealthy Polish–Lithuanian family, provided the main impetus for the re-creation of an independent Polish Army. In the political realm, Roman Dmowski, product of a Warsaw blue-collar family, worked to develop a sense of Polish nationalism at home and lay the groundwork for international recognition of a Polish state. However, neither Piłsudski nor Dmowski could have achieved much success unless fate had thrown them an unusually fortunate set of international circumstances. As long as Imperial Germany, Russia and Austria-Hungary were strong, Poles could not hope to regain their freedom. However, the assassination of Austria’s Archduke Franz Ferdinand in June 1914 set in motion a sequence of events that would eventually incapacitate all three of Poland’s occupiers.

Both Piłsudski and Dmowski spent their youth in the Russian-occupied region of Poland, but later relocated to the Austrian-occupied region in the decade prior to the outbreak of the First World War. From the beginning, Piłsudski followed the path of violence and hoped to lead another armed insurrection against Russian rule. He rejected any idea of co-operation with the Russians, regarding it as tantamount to collaboration. Consequently, young Piłsudski quickly ran afoul of the Russian police and spent five years in Siberian exile. After his exile, Piłsudski became involved in socialist politics and joined the Polish Socialist Party (Polska Partia Socjalistyczna or PPS), while simultaneously engaging in underground revolutionary activities. By 1904, Piłsudski was able to gather some like-minded individuals and formed a paramilitary unit within the PPS. In contrast, Dmowski believed that armed rebellion was doomed to failure and considered some degree of co-operation with the Russians as essential if Poles were ever to achieve any kind of local autonomy. Since the Russians did not look kindly on Poles forming political organizations, Dmowski was forced to found his National Democratic Party (known as endecja) as a covert organization. When revolution in Russia spread to Poland in 1905, Piłsudski and Dmowski found themselves on opposite sides. Dmowski formed a militia that worked with the Russians to suppress the rebellion, which helped to foster permanent enmity with Piłsudski. Furthermore, Piłsudski’s preference for armed rebellion led to a split in the PPS.

Following the failed 1905 Revolution, Piłsudski relocated to Austrian-controlled Kraków with his remaining confederates while Dmowski joined the Russian Duma as a Polish delegate. The Austrians regarded Piłsudski as useful and allowed him to form several small Polish paramilitary organizations, which could be used to conduct sabotage and terrorist-style raids into the Russian-controlled region of Poland. Hauptmann Włodzimierz Zagórski, an ethnic Pole serving in the Austro-Hungarian General Staff, served as primary liaison between the Austrian military and Piłsudski’s paramilitaries. Piłsudski had a tendency to resent professional military officers, since he lacked their training, and his methods seemed more like gangster tactics. In September 1908, Piłsudski led a successful raid near Vilnius which robbed a Russian mail train of about 200,000 rubles; Piłsudski used the funds to expand his covert organizations. Piłsudski’s long-term vision was to create a pool of armed and trained Poles who could be used to eventually fight for Polish independence. However, the Austro-Hungarian Army was not keen on subsidizing international train robberies and thereafter tried to keep Piłsudski on a short leash. Nevertheless, by the time that Gavrilo Princip assassinated the Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand in June 1914, Piłsudski had a solid cadre of Polish insurgents, which he wanted to march into Poland to instigate an anti-Russian rebellion. Without asking permission from the Austrian authorities, Piłsudski launched his own invasion with 400 troops on 6 August and occupied the city of Kielce a week later. As soon as the Austrians discovered this unauthorized military action, they demanded that Piłsudski’s troops be incorporated into the Austro-Hungarian Army; after three weeks of dithering, which he used to gather more recruits, Piłsudski agreed. He began forming the Polish Legions, three brigade-size units that would fight on the Eastern Front in 1914–16. In order to keep close control on Piłsudski, Hauptmann Zagórski was made chief of staff of the Legions.

Poles have tended to exaggerate the actual accomplishments of the Polish Legions, but there is no doubt that Piłsudski was able to amass a cadre of veteran soldiers who would become the backbone of Poland’s armed forces for the next three decades. It is also true that the Legion officers were a picked lot; they were well-educated men who were also intensely patriotic and loyal to Piłsudski. For example, Kazimierz Sosnkowski, chief of staff of the Legions’ 1st Brigade, had been with Piłsudski since his PPS days and was a scholar who could speak seven languages. Władysław Sikorski, a university-trained engineer with a reserve commission in the Austrian Army, played a major role in training the Legions’ nascent officer corps. Another rising star in the Legions was Edward Rydz-Śmigły. Meanwhile, Dmowski worked within the Russian political system, trying – and failing – to gain any concessions to Polish autonomy in return for support in the on-going war.

While agreeing to work with the Austrians, Piłsudski saw this as only a temporary measure and continued his own plans to build a military apparatus that could achieve Polish independence by force. Shortly after agreeing to form the Legions, he established the covert Polish Military Organization (Polska Organizacja Wojskowa or POW), which was intended to conduct subversion and propaganda behind Russian lines in Poland. When the Germans occupied Warsaw in August 1915, the POW came out into the open and formed its first battalion. At this point, Piłsudski hoped to disband the foreign-controlled Legions and expand the POW into a Polish Army under his command. However, neither Germany nor Austria-Hungary were interested in allowing an independent Polish Army and the POW battalion was integrated into the Legions. Although Russia was clearly losing the war by 1916, the Central Powers were also beginning to run out of infantry replacements and decided to seek greater Polish participation by issuing a decree that promised to create a new Kingdom of Poland after the war was won. However, Piłsudski could see that these were empty promises and that Germany would not allow true Polish independence. After the February Revolution in 1917 and the abdication of the tsar, the Germans were eager to transfer troops west to fight the Allies. Piłsudski’s Polish Legions had grown to nearly a corps-size formation and Austria-Hungary agreed to transfer these troops to German command. However, Piłsudski refused to serve under German command, as did many of his troops (the so-called ‘Oath Crisis’), so he was jailed and his troops scattered. Zagórski had urged the legionnaires to take the oath, which blackened his name in the eyes of many of Piłsudski’s acolytes. Other Poles, including Władysław Sikorski, either joined the German-organized Polnische Wehrmacht (Polish Armed Forces) or the Austrian-organized Auxiliary Corps. Before his arrest, Piłsudski appointed Edward Rydz-Śmigły as the new head of the POW, which went underground again.

Meanwhile, Dmowski had recognized that tsarist Russia was losing the war and he went to England and France in 1917 to espouse the idea of Polish autonomy. On 15 August 1917, in France, Dmowski created a new Polish National Committee aimed at rebuilding a Polish state, which included the famed pianist Ignacy Paderewski. Within a month, the French recognized the committee as the legitimate representatives of Poland and promised to help form a Polish volunteer army in France to support the Allies. The Allied governments released expatriate Poles in their own armed forces and encouraged recruitment overseas, particularly in Canada and the United States. Generał Józef Haller, one of the brigade commanders in the Polish Legions, managed to escape to France in July 1918 and he seemed the perfect leader for the Polish expatriate army being formed. Haller’s so-called ‘Blue Army’ was slowly trained and equipped by the French, but did not see any combat on the Western Front until July 1918. When the Armistice was announced in November, Haller had two well-equipped divisions under his command, with three more divisions and a tank regiment forming. The French were also training Polish pilots, in order to form seven aviation squadrons. Haller’s Blue Army was loyal to Dmowski’s Polish National Committee in Paris. Dmowski and Paderewski also helped to steer opinions in the Allied camp towards favouring the restoration of a Polish state after the war was concluded. President Woodrow Wilson’s Fourteen Points clearly enunciated this aspiration in January 1918, although there was little discussion about Poland’s potential borders.

While the Allies were defeating Imperial Germany, Piłsudski was cooling his heels in Magdeburg fortress for 16 months, with his deputy, Kazimierz Sosnkowski. When revolution in Germany forced Kaiser Wilhelm II to abdicate, the caretaker government released Piłsudski and allowed him to leave by train for Warsaw. Although the Germans attempted to coerce Piłsudski into making various pledges, he refused to make any concessions. The Regency Council, established by the Germans, held residual civilian authority in Warsaw. Recognizing the need for military advice, the council selected Colonel Tadeusz Rozwadowski, an Austrian-trained artilleryman, to organize an independent Polish military force. When Piłsudski arrived in Warsaw on 10 November 1918, he was met by only a few members of the POW. Nevertheless, the next day Piłsudski managed to browbeat the council into appointing him as commander-in-chief of the Polish armed forces and to dismiss Rozwadowski. He then began forming a national government – making him a de facto military dictator. Aside from his titles, Piłsudski was only able to cobble together a force of about three infantry regiments (9,000 troops) under his command. In contrast, the Ober Ost (German Army in the East) had over 80,000 troops in Poland (mostly from General Erich von Falkenhayn’s 10. Armee, 10th Army), but their military discipline was collapsing. Piłsudski met with the local German commander and negotiated an agreement, whereby the German Army would leave the area within ten days in return for no harassment by the Poles. Piłsudski’s troops eagerly began disarming the evacuating German troops, acquiring large stocks of weaponry and ammunition. A similar process occurred in southern Poland, where Austrian troops were also disarmed. Thus when the Armistice ended the First World War on 11 November 1918, the new Polish republic found itself with two groups claiming to be the legitimate government of Poland: Dmowski’s in Paris and Piłsudski’s in Warsaw. Five days later, Piłsudski announced the re-creation of an independent Polish state, to be known as the Second Republic. Surprisingly, Italy was the first country to recognize independent Poland.

It is important to note that Piłsudski and Dmowski had radically different visions for the new Poland; the former intended to create a socialist-tinged, secular and multi-ethnic state with expanded territorial buffers to help defend against future German and Russian aggressions. In contrast, Dmowski wanted to build a homogenous state based upon a Catholic, ethnic Polish majority. He regarded the inclusion of minorities (Czechs, Germans, Ukrainians, White Russians, Jews) as a dangerous liability who might provide grounds for Poland’s neighbours to seek future border adjustments. These two competing visions were never reconciled in the Second Republic.

As Austrian, German and Russian authority evaporated in eastern Europe, the political situation became extremely fluid. In particular, the German evacuation left a vacuum in the eastern borderlands, which the Poles referred to as Kresy Wschodnie. Ukrainian nationalists seized part of Lwów and proclaimed a republic – which immediately sparked conflict with local Polish militiamen. In Wilno, Lithuanian nationalists were agitating to claim that city for themselves, as well. Czechs and Romanian troops also were mobilizing to seize contested border areas. Meanwhile, the Western Allies – particularly Britain – sought to impose limits upon the new Polish state by proposing the so-called Curzon Line, which would deprive Poland of both Lwów and Wilno. Piłsudski simply ignored this unsolicited proposal and mobilized as many troops as possible to fight for the eastern border regions. However, the Polish Second Republic was in poor shape from the outset, having suffered significant damage to its infrastructure after four years of fighting during the First World War: cities and towns had been looted or burned, industrial production was negligible, the agricultural situation was grim and about 450,000 Poles had died in the war. Before evacuating, the Germans sabotaged much of the rail network in Poland and destroyed 940 train stations. Poland was even stripped of horses, which made it difficult to form cavalry units. Furthermore, there were no arms industries in Poland because the occupying Germans and Russians had not wanted the risk that they might be seized by Polish rebels. Nevertheless, Piłsudski was able to rally just enough troops to relieve the Ukrainian siege of Lwów, but his forces were still too badly outnumbered by the Ukrainian nationalists to achieve more. Yet, Piłsudski and many Polish nationalists – aside from Dmowski’s faction – were committed to recovering Kresy for the Second Republic, ensuring further bloodshed.

In addition to committing forces to secure Galicia from the Ukrainians, Piłsudski also encouraged an anti-German revolt in Poznań, which began in late December 1918. Thousands of ethnic Poles in the disintegrating German Imperial Army defected to the rebels, providing them a solid core of trained soldiers, but there were still enough residual German troops in Pomerania to contest control of the region for six months. The rebels formed a separate Polish military formation known as the Greater Poland Army (Wojska Wielkopolska), which was able to amass nearly 90,000 troops by early 1919. In response, the Germans formed Freikorps and border units (Grenzschutz Ost) to launch vicious counter-attacks against the Polish rebels.

In Warsaw, Piłsudski faced great difficulty in organizing a re-born Polish Army (Wojsko Polskie), which was a hodgepodge force from the beginning. The veteran troops had been trained and fought under Austrian, German and Russian command, so there was no common doctrine. Weapons and equipment came from a variety of sources and there was a persistent shortage of ammunition. Thousands of patriotic volunteers also flocked to the colours, including many Lithuanians. Nevertheless, Piłsudski only had 110,000 troops under his control at the start of 1919, which was inadequate to deal with multiple border conflicts. It was not until March 1919 that the Polish government was sufficiently organized to introduce conscription. However, only 100,000 rifles and 12,000 machine guns were available, so foreign military aid was essential to build a more effective military force.

The year 1919 began badly for the Second Republic. Officers loyal to Dmowski attempted a coup against Piłsudski in Warsaw, but this effort quickly failed. The Czechs took advantage of Piłsudski’s pre-occupation with Galicia and internal politics to seize the Silesian border town of Teschen (Cieszyn), which actually had a Polish majority. In the north-west, German forces recaptured some territory lost to the Greater Poland Army. In Galicia, the Ukrainians went on the offensive and nearly retook Lwów, with the outnumbered Poles hanging on by their finger-nails. General Tadeusz Rozwadowski, Piłsudski’s bête noire, played a major role in the defence of Lwów. Hard-pressed, the Polish garrison in Lwów was forced to employ female troops in the front line. The fighting around Lwów was also noteworthy because local Jews sided with the Ukrainians and even formed armed militia units – which would not be forgotten by the Poles. Further north, the Soviet Red Army occupied Minsk and then began tentative probes towards eastern Poland. However, the Red Army was still heavily committed countering a White Russian offensive in southern Ukraine led by Anton Denikin and could not immediately commit large forces against Poland. Even with this caveat, within three months of its re-creation, Poland found itself involved in three major wars against the Germans, Russians and Ukrainians and two hostile border disputes with the Czechs and Lithuanians. The only saving grace was that the popular Ignacy Paderewski returned to Danzig via a British cruiser and agreed to become Piłsudski’s prime minister and foreign minister, which helped to prevent a Polish civil war between opposing factions. Piłsudski blocked Dmowski’s efforts to join the government and instead insisted that he serve as Poland’s primary delegate at the Versailles peace conference. Dmowski worked assiduously with the French to get Haller’s Blue Army transported to Poland and to secure material assistance for Poland’s war effort. Indeed, Dmowski’s diplomacy quickly provided great benefits for Piłsudski when the first elements of Haller’s 65,000-man Blue Army reached Poland in April 1919. Furthermore, French diplomatic pressure on the Ukrainians helped limit their advance while Polish forces were still outnumbered. Haller’s army was sent directly to Galicia, where it spearheaded a counter-offensive. Ultimately, Piłsudski’s forces emerged victorious and the Ukrainian-Polish War ended in July 1919, with Lwów in Polish hands. Furthermore, the important oil refinery at Drohobycz, south-west of Lwów, would provide the Polish Second Republic with vital hard currency. Likewise, the Greater Poland Army managed to hold on to Pomerania and the region – including the so-called ‘Polish Corridor’ – until the Allies awarded the region to Poland in the Treaty of Versailles in June 1919.