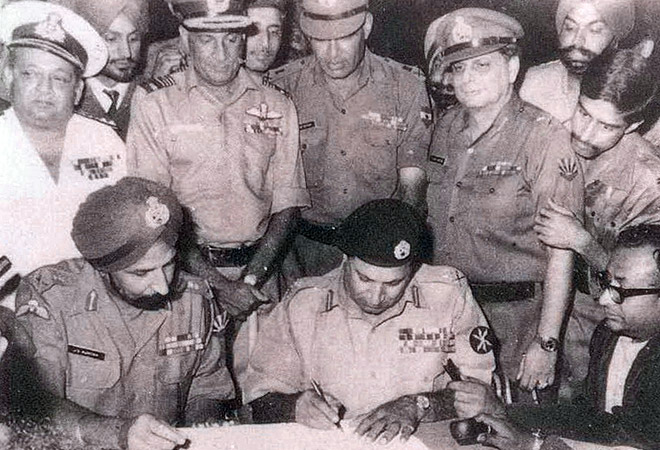

Signing of the instrument of surrender in Dhaka, 16 December 1971.

Uniformed East Pakistan rebel forces with armed civilians patrol a street in Jessore, East Pakistan on April 2, 1971 after West Pakistan forces withdrew.

Not everyone gave it the same credence. When Kissinger raised the matter at a WSAG meeting, General John Ryan of the Joint Chiefs of Staff said, “We still think the Indians plan a holding action [in the west]—we don’t think they will push very hard.” He added that “it would take a long time for a transfer of all their divisions.” Joseph Sisco of the State Department said, “Personally, I doubt that that is the Indian objective, but it may be.” Subsequent intelligence from the same source suggested that the Indian prime minister, unlike some of her colleagues, was not interested in attacking Azad Kashmir or West Pakistan. But the inconsistency did not give pause to the White House. Indeed, Nixon wanted to leak the report to the press. Doing so he felt would “make her [Gandhi] look bad.”40 In the end, the report was not leaked; however, it was used by Nixon and Kissinger as the rationale to initiate a series of moves to which they already had been inclined.

First, Nixon decided to cut off economic aid to India. He had been threatening to do this all along. After 3 December 1971, Nixon believed that India would be discredited in the eyes of its Democratic supporters for having started the war. “We don’t like this,” he told Kissinger, “but you realize this is causing our liberal friends untold anguish.” Now this report would ensure that the State Department and the Congress could not oppose the suspension of aid to India.

Second, the White House sought to ensure the flow of arms to Pakistan. Because the Congress had imposed an embargo, the arms shipments had to be arranged through third parties. This, too, had been on their minds earlier. On 4 December, Yahya had told Ambassador Farland that his forces were in “desperate need of U.S. military supplies,” and if the US administration was unable to provide them, “for God’s sake don’t hinder or impede the delivery of equipment from friendly third countries.” On receiving this message, Nixon asked, “Can we help?” Kissinger replied, “I think if we tell the Iranians we will make it up to them we can do it.” The shah of Iran was approached the next day and encouraged to transfer military equipment and munitions to Pakistan.

After receiving the intelligence report, Kissinger took up the matter with the WSAG. The State Department looked into it and concluded that the president could not under law approve such transfers unless he took a policy stance that the United States was willing to supply this equipment directly to Pakistan. Kissinger denounced such reasoning as “doctrinaire.” “The question is,” he told the WSAG, “when an American ally is being raped, whether or not the U.S. should participate in enforcing a blockade of our ally, when the other side is getting Soviet aid.” Thereafter, the United States approached key Muslim countries—Jordan, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey—to supply weapons to Pakistan through an arms back-channel. Pakistan had independently approached these countries, but their willingness to accede to such requests was contingent on receiving assurance from the United States that the matériel sent to Pakistan would be made good. Even after Washington gave these transactions the go-ahead, things did not work out as planned by Kissinger and Nixon. The shah told the American envoy that he could not send Iranian aircraft and pilots to Pakistan because he was not prepared to risk a confrontation with the Soviets. Instead, the shah suggested that he could send his planes to Jordan, which in turn could send Jordanian plans to Pakistan. Iran, in fact, had a secret agreement with Pakistan by which it would assume responsibility for the air defense of Karachi in the event of an India-Pakistan war. Yahya invoked the agreement, but the shah refused to observe the pact, claiming that it was no longer a purely bilateral conflict between Pakistan and India.

Third, Nixon and Kissinger sought to draw China into the fray. They believed that this would not only rattle New Delhi, but also would underscore to Beijing the reliability of the United States. The White House had been eager to establish direct contact with China’s representative at the United Nations to coordinate their moves, but the Chinese were not interested. By the time the CIA input arrived, Nixon had begun to toy with the idea of getting the Chinese to intervene in the crisis. On the evening of 6 December, Nixon told Kissinger, “I think we’ve got to tell them [the Chinese] that some movement on their part we think toward the Indian border could be very significant.” “Damnit,” he exclaimed, “I am convinced that if the Chinese start moving the Indians will be petrified.” Kissinger observed that the “weather is against them [the Chinese].” Nixon, however, believed that China still could make military moves against India. “The Chinese, you know, when they came across the Yalu [in the Korean War], we thought they were a bunch of goddamn fools in the heart of the winter, but they did it.”

Over the next two days, the CIA reviewed China’s military posture along the Indian border and concluded that “the Chinese are not militarily prepared for major and sustained involvement in [the] Indo-Pak war.” But China did retain “the option of a smaller scale effort, ranging from overt troop movements and publicized preparations to aggressive patrolling and harassment of Indian border outposts on a limited diversionary attack.” The CIA, however, emphasized another aspect of their recent input regarding Gandhi’s cabinet meeting. The prime minister had apparently told her colleagues that if China “rattled the sword,” the Soviets had promised to “counter-balance” any such action.

On the afternoon of 8 December, Nixon and Kissinger met in the Oval Office to take stock of the situation. Kissinger claimed that “the Indian plan is now clear. They’re going to move their forces from East Pakistan to the west. They will then smash the Pakistan land forces and air forces, annex the part of Kashmir that is in Pakistan and then call it off.” After this, he added, “the centrifugal forces in West Pakistan would be liberated. Baluchistan and the Northwest Frontier … will celebrate.” West Pakistan would become like Afghanistan and East Pakistan—another Bhutan. And all of this would have been achieved by “Soviet support, Soviet arms, and Indian military force.” Kissinger warned that “the impact of this on many countries threatened by the Soviet Union,” particularly in the Middle East, would be grim. He also was worried that if the crisis ended in “complete dismemberment of Pakistan,” the Chinese would conclude, “ ‘All right. We [the United States] played it decently but we’re just too weak.’ And that they [the Chinese] have to break their encirclement, not by dealing with us, but by moving either [transcription unclear] or drop the whole idea.” In short, the grand design underpinning their opening with China could crumble in this crisis.

“Now what do we do?” asked Nixon. “We have got to convince the Indians now, we’ve got to scare them off from an attack on West Pakistan,” replied Kissinger. He continued, “We could give a note to the Chinese and say, ‘If you are ever going to move this is the time.’ ” Nixon agreed: “All right, that’s what we’ll do.” Kissinger then added, “But the Russians I am afraid—but I must warn you, Mr. President, if our bluff is called, we’ll be in trouble … we’ll lose.” He then claimed, “But … if we don’t move, we’ll certainly lose.” Nixon said, “I’m for doing anything,” but “we can’t do this without the Chinese helping us. As I look at this thing, the Chinese have got to move to that damn border. The Indians have got to get a little scared.” He instructed Kissinger to convey this message to the Chinese.

Later that evening, Nixon reiterated his belief that China could exercise a restraining influence on India. “I tell you a movement of even some Chinese toward that border could scare those goddamn Indians to death.” The next morning, Kissinger grumbled to the president that the State Department was not sticking to the tough line coming out of the White House. For a moment, Nixon took off his blinkers: “Let’s look … at what the realities are … The partition of Pakistan is a fact.” Why, then, he asked, “are we going through all this agony?” Kissinger promptly stiffened the presidential spine: “We’re going through this agony to prevent the West Pakistan army from being destroyed. Secondly, to maintain our Chinese arm. Thirdly, to prevent a complete collapse of the world’s psychological balance of power, which will be produced if a combination of the Soviet Union and the Soviet armed client state can tackle a not so insignificant country without anybody doing anything.” It is evident that the notion of West Pakistan being destroyed was merely bolstering a position that stemmed from their wider, reputational concerns.

Kissinger sought and obtained a meeting with the Chinese representative to the United Nations, Huang Hua, on 10 December. He conveyed a message from Nixon that “if the People’s Republic were to consider the situation on the Indian subcontinent a threat to its security, and if it took measures to protect its security, the US would oppose the efforts of others to interfere with the People’s Republic.” The “immediate objective” must be to prevent India from attacking West Pakistan. If nothing was done to stop this, “East Pakistan will become a Bhutan and West Pakistan will become a Nepal. And India with Soviet help would be free to turn its energies elsewhere.”

Huang’s response was primly diplomatic. China’s position, he said, was “not a secret.” The stand taken by them in the United Nations was “the basic stand of our government.” By contrast, the US stance was “a weak one.” India and the Soviet Union were “on an extremely dangerous track.” That said, Huang retreated to the fortress of philosophy and first principles. “We have an old proverb: ‘If light does not come to the east it will come to the west. If the south darkens, the north must still have light.’ And therefore if we meet with some defeats in certain places, we will win elsewhere.” Kissinger grew impatient: “We agree with your theory, [but] we now have an immediate problem.” When Huang refused to rise to bait, Kissinger bluntly said, “When I asked for this meeting, I did so to suggest Chinese military help, to be quite honest.” But, he added, “This is for you to decide. You may have other problems on many other borders.” Huang undertook to convey Nixon’s message to Zhou Enlai.

By the time Kissinger met Huang, the White House had set in motion two other consequential decisions. The first was to increase pressure on the Soviet Union to lean on India. In response to Nixon’s back-channel message and letter, the Soviets had maintained that it was imperative to obtain both a ceasefire and a political settlement that reflected the Bengalis’ wishes. They had also criticized Nixon’s insistence that the crisis represented a “watershed” in their relationship. Such an attitude would “hardly help” in finding a solution to the problem at hand. This reply was received late on the night of 6 December, a few hours after the CIA had passed on its information on Indian plans. The day after, Kissinger’s deputy, Alexander Haig, called Vorontsov and demanded a written reply to Nixon’s letter. The president, he added, “wanted it understood that the ‘watershed’ term which he used was very, very pertinent, and he considers it a carefully thought-out and valid assessment on his part.”

In their meeting on 8 December—when Nixon asked Kissinger to approach the Chinese—Kissinger argued that militarily they “had only one hope now.” This was “to convince the Indians the thing is going to escalate. And to convince the Russians that they are going to pay an enormous price.” Aside from getting the Chinese to move, they could “take an aircraft carrier from Vietnam into the Bay of Bengal … We don’t say they’re there to—it would be a mistake. We just say we’re moving them in, in order to evacuate American civilians.” “I’d do it immediately,” said Nixon; “I wouldn’t wait 24 hours.” Kissinger said that they should also send a “stem-winder of a note to the Russians to tell them that it will shoot everything, it will clearly jeopardize everything we have.” He insisted that “we should do it all together.” Pakistan, Nixon observed, was “going to lose anyway. At least we make an effort, and there is a chance to save it.”

That evening, Nixon reverted to the idea of tightening the screws on the Soviet Union and raising the stakes for Moscow. He felt that they should perhaps tell the Russians that “we feel that under the circumstances we have to cancel the summit [scheduled for 1972] … It’s a tough goddamned decision.” Kissinger felt that if they “play it out toughly” Nixon could “go to Moscow with [his] head up.” But “if you just let it go down the drain, the Moscow summit may not be worth having.” He argued that “if they maintain their respect for us even if you lose, we still will come out all right.” “You mean, moving the carrier and letting the few planes [from Jordan] go in and that sort of thing[?]” Nixon asked. Kissinger maintained that it was a question of rescuing US credibility in a crisis “where a Soviet stooge, supported with Soviet arms, is overrunning a country that is an American ally.”

In the meantime, Brezhnev had sent a conciliatory reply to Nixon, saying that the Soviets were “profoundly concerned” about the situation in the subcontinent and reiterating that they wished to move toward a ceasefire and political negotiations between the Pakistan government and the Awami League leaders. On the morning of 9 December, Vorontsov met with Kissinger to hand over this letter. Kissinger said that if India turned against West Pakistan “in the wake of East Pakistan” and tried “to secure a complete victory,” then the US would prevent a crushing defeat of Pakistan and even be willing to take steps of a military nature. “The Indians must not forget,” Kissinger said pointedly, “that the U.S. has allied commitments with respect to defending Pakistan.”

Later that day, Nixon met with the visiting Soviet agriculture minister, Vladimir Matskevich. He observed that “a great cloud” hung over the subcontinent and that it threatened to “poison this whole new relationship [between the United States and the Soviet Union] which has so much promise.” He added, “If the Indians continue to wipe out resistance in East Pakistan and then move against West Pakistan, we then, inevitably, look to a confrontation. Because you see the Soviet Union has a treaty with India; we have one with Pakistan.” He needed the urgency of obtaining a ceasefire to be understood in Moscow.

Nixon and Kissinger’s references to US treaty commitments were significant. The previous evening, Kissinger had urged Pakistan’s ambassador to communicate with the State Department and formally invoke its “mutual security treaty.” But there was, in fact, no such treaty. The only extant agreement, which had been signed in March 1959 under the Eisenhower administration, pertained to commitments under Pakistan’s membership in the Baghdad Pact and dealt with the contingency of aggression by a communist country. This agreement was never submitted to the Congress, let alone ratified. Kissinger frequently referred to a commitment made under the Kennedy administration, which was an assurance given (in an aide-mémoire) to Ayub Khan in late 1962 that the United States would come to Pakistan’s aid if it was attacked by India. This had been extended to Ayub to assuage his concerns about the flow of US arms to India after the latter’s war with China, but it certainly did not amount to a “treaty” of any kind.

The White House could, however, count on Moscow being unable to parse such distinctions. When meeting with Vorontsov on the morning of 10 December, Kissinger claimed that there was “a secret protocol” in the US-Pakistan agreement, and he shared the aforementioned aide-mémoire with him. Kissinger said that the US military had already been ordered to begin preparations for possible military aid to Pakistan. These would be conducted in secret until 12 December under the pretext of “tactical redeployments” related to Vietnam. By Sunday, 12 December, the administration would have to make the final decision on whether to intervene in favor of Pakistan.

Kissinger’s ploy had the desired effect of setting a cat among the Soviet pigeons. In a telegram to Moscow marked “Extremely Urgent,” Vorontsov noted that from Kissinger’s language he could infer that this military aid “involves moving U.S. aircraft carriers, and naval forces in general, closer to the subcontinent.” The Americans, he wrote, “are only interested in the situation on the western border between Pakistan and India … Right now the White House clearly feels that the military aspect of the conflict in East Pakistan had already been decided in favor of India, and they are turning a blind eye to it.”

This was, of course, partially mistaken. Nixon and Kissinger believed that there was an outside chance for a ceasefire before the Pakistan army caved in on the eastern front. But Vorontsov’s reference to the movement of the aircraft carrier was correct. That same day, Nixon instructed the chief of naval operations, Admiral Elmo Zumwalt, to assemble an impressive naval task force and move it off the coast of South Vietnam, into the Malacca Straits, and onward to the Bay of Bengal. Task Group 74 included the largest aircraft carrier in the US navy, the USS Enterprise.

No sooner had Moscow learned of Nixon and Kissinger’s statements to Matskevich and Vorontsov than it began to lean on New Delhi.66 Such was the urgency with which the Soviets conveyed their concerns that Indira Gandhi decided to send her trusted adviser D. P. Dhar to meet with the top Soviet leaders. Dhar left on the morning of 11 December carrying with him a missive from Mrs. Gandhi to Kosygin. “We have no design on the territory of others,” she wrote, “nor do we have any desire to destroy Pakistan.” As far as India was concerned, “we could cease fire tomorrow and even withdraw our forces to our own territory if the rulers of Pakistan would withdraw their forces from Bangla Desh and reach a peaceful settlement.” For India now owed allegiance to the government of Bangladesh. “Without such a settlement,” she insisted, “10 million refugees will not return to their homeland.” A call to ceasefire “coupled with expressions of hope” about the return of refugees had “no purpose other than to cover up the annihilation of an entire nation.” Indian forces fighting with the Mukti Bahini, she observed, had achieved “significant results.”

The Indian army had indeed made significant progress by this time. In particular, troops from the IV Corps stood on the eastern banks of the Meghna River on 9 December. Their commander had Dhaka in his sights, but had no firm orders to move ahead. Nor did he have the requisite river craft to attempt a crossing, the bridge having been blown up by the retreating Pakistani forces. General Sagat Singh liaised with the commander of the helicopter unit attached to his corps, and he arranged for an airlift of a sizable force. By the morning of 11 December, about 650 Indian troops were on the west bank of the Meghna.

At this point, Dhaka came into the sights of the Indian leadership. The threat of an American intervention as well as Moscow’s nervy reaction to it convinced New Delhi that its political aims could be only attained by a decisive military victory involving the capture of Dhaka and the surrender of Pakistani forces. This shift in objectives was also influenced by another development.

On the morning of 10 November, Governor A. M. Malik of East Pakistan sent a ceasefire proposal to the senior UN official in Dhaka, Paul Marc Henri. Over the previous few days, it had become increasingly clear that the defenses of the Pakistan army in East Pakistan were collapsing. The Pakistani military strategy in the eastern sector was to fight for territory at the border, fall back to fortified positions in the rear, and use these to interdict Indian maneuvers inside East Pakistan. It has been frequently argued since then that the Pakistan army should have concentrated on the defense of Dhaka instead of spreading itself thin along the borders, but this perspective overlooks the point that the Pakistani strategy was premised on the expectation that India would aim to carve out territory in which to install the Bangladesh government—an assumption that was not far from reality. The problem lay in accomplishing staged, successful withdrawals—not an easy maneuver under the best of conditions.

On 7 December, Governor Malik had sent a telex message to Yahya suggesting that Pakistan should propose a political solution at the United Nations to obtain a ceasefire. The president’s office had replied the next day asking the governor to continue the fight, informing him that a high-powered delegation was being “rushed” to the United Nations. However, the military position was worsening over time. On 9 December, General Niazi—the theater commander—sent a message to Rawalpindi painting a dismal military picture: “situation extremely critical … we will go on fighting and do our best.” Niazi requested strikes on Indian air bases in the theater as well as airborne troops for the defense of Dhaka. In another message the following day, Niazi wrote, “orders to own troops issued to hold on [until the] last man last round which may not be too long … submitted for information and advice.” In response, Yahya authorized the governor to take the necessary steps to prevent the destruction of civilians and to “ensure the safety of our armed forces by all political means that you will adopt with our opponent.”

After that, the military adviser to the governor, Major General Rao Farman Ali Khan, drafted the proposal that would be handed to Henri at 1:00 PM on 10 December. The proposal stated that the governor invited the elected representatives of East Pakistan to “arrange for the peaceful formation of the government in Dacca.” Five requests were addressed to the United Nations: an immediate ceasefire, the repatriation of the armed forces to West Pakistan, the repatriation of all West Pakistan personnel, the safety of all persons settled in East Pakistan since 1947, and a guarantee of no reprisals. Although this was “a definite proposal” for a peaceful transfer of power, the “surrender of Armed Forces will not be considered and does not arise.”

When Yahya received a copy of the proposal, he was incensed. Reproving Malik for having “gone much beyond” his brief, Yahya observed that the proposal “virtually means the acceptance of an independent East Pakistan.” The prevailing situation required only a “limited action by you [Malik] to end hostilities in East Pakistan.” Yahya quickly distanced himself from this proposal, but not before it had circulated in key chanceries, including among the Indians. New Delhi now knew that the Pakistan army was on the brink of collapse in the eastern theater. This gave further impetus to the emerging decision to strike for Dhaka as well. At 4:00 PM on 11 December, an Indian parachute brigade was dropped at Tangail. The race for Dhaka had begun—but the road would turn out to be tortuous.

On reaching Moscow, D. P. Dhar called on the Soviet premier to hand over the letter from Indira Gandhi. Alexei Kosygin was exceedingly nervous, “shaking like a leaf.” He asked Dhar about the progress of operations and about India’s further intentions. “You must finish fast,” he insisted. Kosygin also informed Dhar that their first deputy foreign minister, Vasily Kuznetsov, was leaving for Delhi to consult with the Indian leadership. The Soviets had been tracking the movement of the US naval task force sailing to the Bay of Bengal. They were deeply perturbed at the prospect of an escalatin of the conflict and of their being drawn into it.

In his meeting with Haksar on 12 December, Kuznetsov probed India’s objectives on the western front. He emphasized that the US commitment to defending the territorial integrity of West Pakistan was “of a nature and character that any provocation on our [India’s] part that might lead U.S.A. to conclude that we have territorial ambitions in west Pakistan would enlarge the conflict.” New Delhi was already aware of this possibility, as the foreign ministry had prepared an assessment of US obligations to Pakistan. The note focused on the 1959 agreement and concluded that the contents were “elastic enough” for Pakistan to invoke it. Whether the United States acceded to this request would depend on “how far the U.S.A. will find it politically expedient” to interpret the agreement in wide terms. By the evening of 10 December, the Indian navy was picking up signal intelligence about the impending move of the US task force. Two days later, the New York Times published the news. The Indian embassy in Washington believed that three marine battalions had been “placed on the standby for emergency airlift” and that a “bomber force aboard the ‘Enterprise’ had the US President’s authority to undertake bombing of Indian Army’s communications, if necessary.” New Delhi was anxious that the United States had a plan or an intention to establish “a beachhead” in some part of East Pakistan to help with the withdrawal and evacuation of Pakistan forces.

The dispatch of USS Enterprise influenced Indian strategy in two different ways. As far as the eastern front was concerned, India decided to accelerate the tempo of operations and conclude them before the task force entered the waters of the Bay of Bengal. “Far from fraying our nerves,” Haksar conveyed to Kuznetsov, “it is promoting greater determination.” The army chief sent a succession of messages to General Farman Ali in Dhaka urging him to surrender. “My forces are now closing in around Dacca and your garrisons there are within the range of my artillery.” Further resistance was “senseless,” he stated. Manekshaw assured him of “complete protection and just treatment under Geneva Convention” to all military and other personnel who surrendered to Indian forces. At the same time, Manekshaw instructed the eastern army command to immediately capture all the towns in East Pakistan that Indian forces had bypassed: Dinajpur and Rangpur, Sylhet and Mynamati, Khulna and Chittagong. He was evidently concerned that if a ceasefire was declared soon, Indian troops would be in control of only two towns, Jessore and Comilla. The move to wind back and take control of the other locations would have entailed a significant—arguably fatal—diversion of resources from the drive toward Dhaka. However, fortunately for India, the commanders on the ground, instructed by General Jacob, disregarded the army chief’s orders and maintained the momentum of the push to Dhaka.

As far as the western front went, India exercised considerable circumspection to avoid giving any pretext to the United States for intervention. Haksar asked Mrs. Gandhi to convey to the army chief “that the complex political factors dominating our Western front with Pakistan require extreme care on our part.” He also wrote to the defense secretary that “anything that we may do or say which gives the impression that we have serious intentions, expressed through military actions or dispositions or propaganda, that we wish to detach parts of West Pakistan as well as that of Azad Kashmir would create a new situation.”

Furthermore, India reassured the Soviet leadership that “we have no repeat no territorial ambitions anywhere either in East or West Pakistan. Our recognition of Bangladesh is a guarantee against any territorial ambitions in the East and our position in the West is purely defensive.” New Delhi also requested that Moscow “make a public announcement carrying the seal of the highest authorities in the Soviet Union that involvement or interference by third countries in the affairs of the sub-continent cannot but aggravate the situation in every way.” The Soviets welcomed the Indian assurance, but declined to make the announcement requested by India. They strongly felt that the longer the war dragged on, the higher was the possibility of US intervention.

Meanwhile, Nixon and Kissinger were anxiously awaiting Beijing’s response to their request. “I am pretty sure,” said Kissinger, “the Chinese are going to do something and I think that we’ll soon see.” On the morning of 12 December, Nixon decided to send a message to Moscow that reiterated his stance. “We’re not letting the Russians diddle us along,” he said. Kissinger replied, “It’s a typical Nixon plan. I mean it’s bold. You’re putting your chips into the pot again. But my view is that if we do nothing, there’s a certainty of a disaster … at least we’re coming off like men. And that’s [sic] helps us with the Chinese.” Kissinger informed Nixon that the task force would be in the Indian Ocean the next day.

Haig interrupted the conversation and said that the Chinese wanted urgently to meet. Because Nixon and Kissinger were leaving for the Azores, they had suggested this meeting in New York with Haig. China’s request for a meeting was “totally unprecedented,” said Kissinger. It meant “they’re going to move. No question they’re going to move.” A fantastic exchange ensued. “If the Soviets move against them [the Chinese],” said Kissinger, “and then we don’t do anything, we’ll be finished.” Nixon asked, “So what do we do if the Soviets move against them? Start lobbing nuclear weapons in, is that what you mean?” Kissinger replied, “Well, if the Soviets move against them in these conditions and succeed, that will be the final showdown.” He added, “If the Russians get away with facing down the Chinese, and if the Indians get away with licking the Pakistanis … we may be looking right down the gun barrel.”