The collapse of the North African Campaign in May 1943 came as a shock to the Italian people. They knew that their armed forces had suffered reverses in the desert, but total defeat seemed beyond the realm of possibility. They seemed to be clearly winning the war–with some important reverses–from June 1940 to July 1942. How could such a reversal of fortunes have occurred? How could the domination of Mare Nostro have slipped away from the Regia Marina without its magnificent fleet being defeated in a major battle?

Mussolini himself would have difficulty answering such questions. Incredibly perhaps, his popularity suffered little with the loss of his empire. Secret polls conducted separately by the Fascist Party and the hostile House of Savoy, whose pro-British aristocrats were looking for an end to both the Duce and hostilities, both agreed that the majority of Italians were more inclined to blame the ineptitude of his generals (a not entirely unfounded accusation) than his own leadership. Mussolini ha siempre raggione! – “Mussolini is always right!”–still held sway. Appalled as they were by the surrender in North Africa, an enemy invasion of the homeland was out of the question, because popular confidence in national defense rested chiefly on Pantelleria.

Lying between Tunisia and Sicily, the tiny island was universally regarded as the ‘Italian Gibraltar’, a fortified outpost bristling with huge artillery and hundreds of lesser guns manned by companies of elite troops; a sheltered harbor protecting flotillas of torpedo-boats; and a squadron of the Regia Aeronautica’s finest pilots and planes. Military propaganda had for years depicted Pantelleria, less than half the size of Malta, as an unassailable bastion shielding the entire Central Mediterranean from regional contingencies, such as the fall of North Africa. The image of an anchored, unsinkable super-battleship was applied to the island.

This characterization, while over-stated for mass-consumption, may have been at least partially accurate until the first year of the war, when Pantelleria’s supplies of arms and ammunition were steadily raided by Commando Supremo procurement officials to make up for accumulating losses in Libya and Tunisia. By late 1942, the island had been mostly stripped of its defenses, reduced to a fraction of their former capabilities. This ‘floating fortress’ upon which the Italian people based their faith in ultimate victory, or, at any rate, in a stalemate that would stave off invasion, was no longer able to protect itself, let alone southern Europe.

But the Allies were likewise deceived. They too, believed in Pantelleria’s formidable reputation, and were certain the whole Mediterranean Theater hinged on its seizure. A major air-sea operation was designed to limit casualties, which were expected to be high, regardless of any precautions. Several USAAF bomber squadrons were prepared for large-scale raids against the island, accompanied by a naval blockade. Landings would take place only after resistance had been impaired, but high losses were officially anticipated.

“The Italians did not fight with much enthusiasm in North Africa”, General Dwight Eisenhower, commanding U.S. troops in newly conquered Tunisia, told his military colleagues on the eve of the assault.” But they can be expected to resist fiercely, once their homelands are threatened.” British Field Marshal Montgomery observed in an aside to French General Marcel, “if they behave as the Yanks did at the Kasserine Pass, we should have no difficulty taking Pantelleria.” The barb was one of numerous taunts typifying ill will among U.S. and British commanders throughout the war, and referred to 30,000 American troops routed by the Afrika Korps just three months earlier in Tunisia.

In truth, conditions for the 7,000 poorly armed soldiers and 10,000 impoverished civilians of Pantelleria were dire. Neither food nor supplies of any kind had reached them since January, and drinking water had become so scarce, military and civilian personnel alike relied mostly on the central island’s three natural wells to relieve their thirst. Defenses were down to an insufficient number of anti-aircraft weapons and handful of large guns incapable of covering the entire coast. Against these less than formidable odds, beginning 18 May, the Americans launched 100 heavy and medium bombers in two to four raids every twenty-four hours over the next ten days.

Virtually all defenses were knocked out in short order, save the island’s few, remaining, largest artillery pieces which had been emplaced under natural rock shelters several meters thick. The only three surviving wells were destroyed, and growing numbers of panicked women and children began crowding into caves or underground ammunition storage bunkers, as their sole protection against the murderous onslaught from the sky. With their homes and all public services obliterated, they huddled, starving and ravaged by thirst, amid stacks of live shells they prayed would not explode.

Roads linking defensive positions were rendered impassable by numerous bomb craters, so emergency crews toiled all through the night to repair them, because workers would have been otherwise machine-gunned during daylight hours by enemy fighters flying low-level strafing missions and shooting at anything that moved. Even these after-dark repairs became impossible following the 29th, when American aircraft illuminated the entire island in the brilliance of descending parachute flares. They were thus enabled to commence the round-the-clock, indiscriminate saturation bombing of Pantelleria.

The carnage was bolstered by salvo after salvo fired from destroyers laying off shore. With the roads no longer passable and most telephone wires cut, communication between outposts had to be carried out on foot by couriers who risked their lives venturing beyond the shelter of caves. Unable to sleep or fight back, all the inhabitants could do was to keep their heads down. Their misery was compounded by the destruction of all hospital facilities for the burgeoning cases of wounded, who were cared for by under-equipped field clinics short on medical supplies of all kinds.

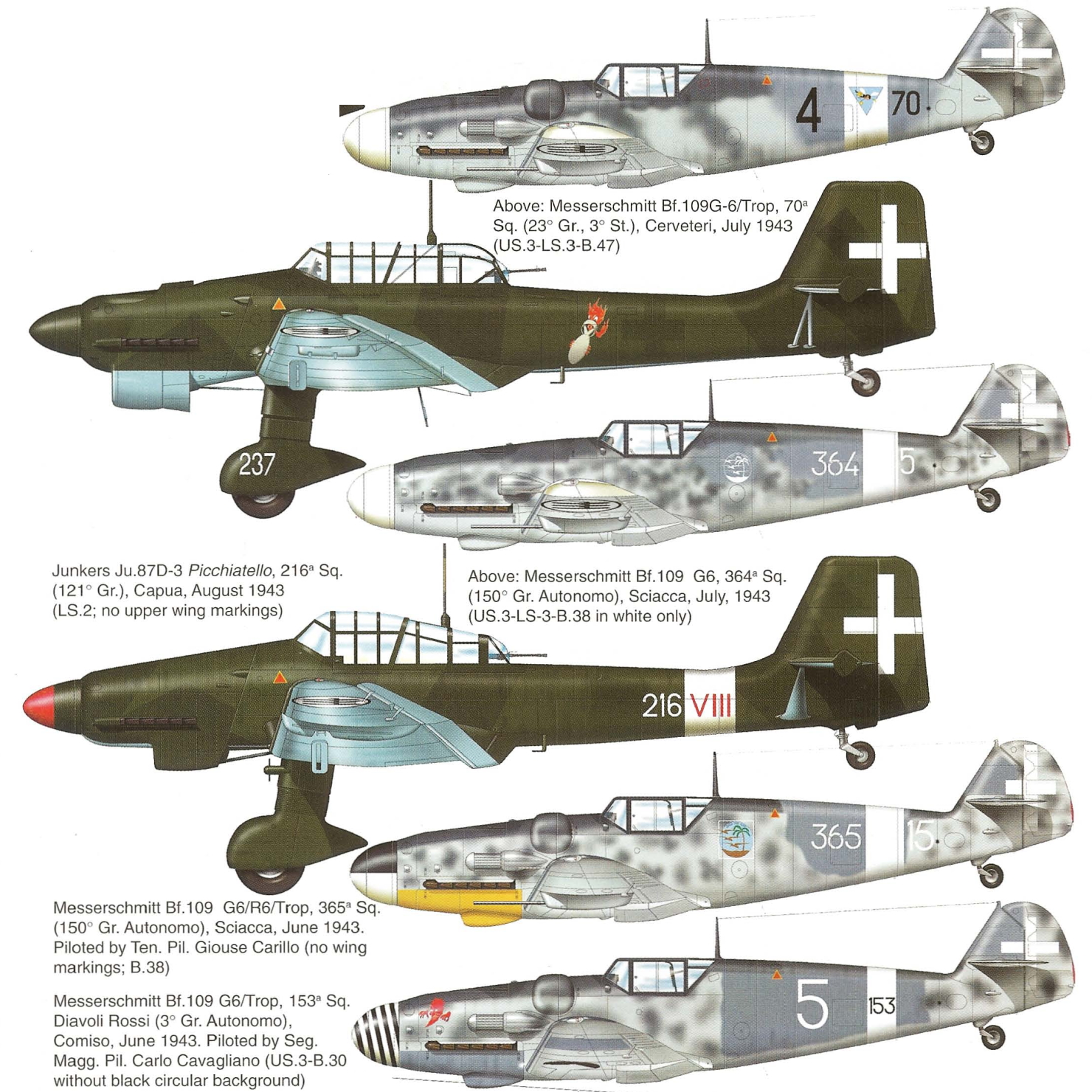

Both German and Italian aircraft made serious, persistent attempts to interdict the U.S. bombers. A communiqué sent from the fighting at Pantelleria to Rome reported that the garrison “has been facing the ceaseless enemy air attacks with unflinching courage, and yesterday destroyed six airplanes.” A later radio message cited “eleven more enemy planes” brought down. But five-to-one odds prevented all save a handful of Junkers or Macchi transports and fighters, usually carrying a few medical or food supplies, from making precarious landings on Pantelleria’s holed runways.

Some 250 Luftwaffe and Regia Aeronautica interceptors fought their way into the skies over Pantelleria during the last eleven days of its merciless siege, shooting down forty-three USAAF and RAF aircraft, while losing fifty-seven of their own. These casualties were prohibitively high, and forced the cancellation of all further assistance by air. Ordinarily effective motor torpedo-boats sortied together against the naval siege, but, minus air cover, they were strafed by hordes of Allied fighters which prevented them from coming within firing range of any targets.

A final, self-sacrificial effort on the part of both Regia Marina sailors and Regia Aeronautica pilots succeeded, however, in punching through the U.S. blockade long enough to allow the passage of a single water-tanker. The ship also carried a vitally needed water purification and distilling plant. Tragically for the thirsty islanders, their port had been so devastated by air-raids, the Arno was unable to deliver this invaluable equipment or a single drop of water, and forced to return to Trepani. On board were 1,000 German troops originally stationed on Pantelleria. Their departure added to the defenders’ demoralization, yet they still refused to surrender.

They had a reputation for incredible toughness going back many centuries. Thirteen centuries before, the entire Christian population had been butchered by Arab invaders, who were pushed into the sea by Roger II leading Italian forces from Sicily during 1123 A.D. 430 years later, Pantelleria was sacked again, this time by the Turks. These historic parallels made some islanders hope that Mussolini would similarly come to their aid from Sicily, and expel these 20th Century versions of 8th Century invaders. But conditions were so awful during the spring of 1943, residents may have felt more like dispossessed persons exiled by the Caesars, who used Pantelleria as a place of banishment during Imperial Roman times.

Sure no one could endure such intense punishment meted out for eighteen consecutive days, the Americans demanded an unconditional surrender from Pantelleria’s governor, Admiral Gino Pavesi. As he explained in a communiqué sent to Rome, “throughout yesterday, 10 June, and last night, heavy enemy bomber and fighter formations followed one another uninterruptedly over Pantelleria, whose garrison, though battered by the onslaught of some 1,000 enemy machines, has proudly left unanswered a fresh demand to surrender.” His refusal to respond prompted the most severe beating yet inflicted on the island. At its eastern end alone, B-24 Liberators dropped in excess of 5,000 tons of high explosives, more than twice the amount that fell on Malta in a single month at the height of Axis air activity in 1942.

On 9 June, as a consequence of this concerted air assault, all of Pantelleria’s fifty-two square kilometers suddenly vanished for the next two days under an immense pall of dust, through which gunners could not sight their field artillery, most of it destroyed, in any case. Just a single pair of anti-aircraft artillery were still operable, but rendered useless by their position high atop Magna Grande, the island’s 837-meter-high volcano.

In the clear, blue skies above this unnatural inferno, Regia Aeronautica pilots, oblivious to the numerical odds against them, fought with unmatched ferocity. In an uneven melee that pitted fourteen Folgores and four Italian-flown Messerschmitt-109s against fifty RAF Spitfires and American P-38s, eight Spitfires were shot down for the loss of three Macchi 202s.

Admiral Pavesi sent a personal telegram to Mussolini, informing him that all further resistance was futile, and, in the name of the civilian population, appealed for permission to surrender. As soon as the Duce granted his request, a white flag was hoisted from the antenna of the island’s only radio station building. Over its microphone Pavesi informed the Allies of his willingness to capitulate.

Allied propagandists juxtaposed his surrender broadcast with the story of Malta, whose stalwart defenders survived more than two years of air-raids, while Pantelleria held out for less than a month. The analogy was used to reaffirm Italian cowardice and general lack of enthusiasm for ‘Mussolini’s war’. Such comparisons were not entirely applicable, however, because Malta suffered only a fraction of the bomb tonnage dropped on much smaller Pantelleria. Even so, the Duce later learned to his chagrin that the actual condition of the beleaguered island contrasted with its dramatic appearance under fire. During the entire siege, the garrison lost just “fifty-six dead and 116 wounded, almost all of them Blackshirts in the anti-aircraft defenses,” he discovered. “The civil population and troops barricaded in the underground hangers had suffered only insignificant losses. The entire garrison of 12,000 men was taken prisoner almost intact … The hangars, dug out of the rock, had nullified the effects of the enemy bombs. The 2,000 tons of bombs certainly did fall on the island, but on rock, not men! … Admiral Pavesi had lied; today we may say that he betrayed us. Not even the underground hangars were demolished, and the airfield was left almost intact.”

While it is true that the garrison, having been cut off from all outside aid, was in no position to have held out indefinitely, the island could have delayed the inevitable, thereby affording valuable time for fortifying Sicily. Pavesi’s imperfect defense, however brief, was not in vain, and resulted in important repercussions for the entire Mediterranean Campaign. Pantelleria had never been a danger to the Allies, who could have sailed past it with impunity toward their invasion of Sicily. By wasting nearly a month in an entirely avoidable expenditure of effort, they provided the Italians with much-needed time to beef-up their Sicilian defenses, which had been no less neglected than those left on Pantelleria. Consequently, Anglo-American troops would pay dearly on the plains of Sicily for this previous diversion to the smaller island.

“It was this damnably stupid ‘island-hopping’ mentality that gave our enemies the luxury of time,” complained General Omar Bradley, “and that needlessly cost so many American soldiers their lives in the Mediterranean. The same misguided strategy was applied in the Pacific, where most islands we took with such heavy losses should have been bypassed, so we could have gone after real objectives to end the war sooner by two years and thousands of less dead G.I.s”

Despite General Bradley’s condemnation of ‘island-hopping’ against both Italy and Japan, Eisenhower granted Mussolini another grace period in yet one more useless operation against an even more insignificant island. For all its virtually non-existent fortifications, the Americans still needed an entire week of massive air raids and naval gunfire to take Lampedusa. With more than a month to prepare for the invasion of southern Europe, Italian troops, accompanied by the Hermann Goering Armored Division, took up their positions in Sicily.

To divert public attention from the apparent calamity at Pantelleria and restore morale, Mussolini ordered a suicidal mission far behind enemy lines, just as Italian defenders of the island capitulated. On 13 June, a lone, long-range transport flew undetected to North Africa. Since the conclusion of the Desert Campaign in May and subsequent concentration of activity in the Central Mediterranean at Pantelleria, Allied security had gone slack in liberated Libya. Counting on American complacency, the tri-motor SM82 “Marsupial” was mistaken by ground observers for a B-17, as it approached Benghazi.

They did not, however, notice two parachutes pop from the aircraft and float to earth. They belonged to a pair of volunteer commandos, who stealthily made their way to the Benina North Airport. Slipping past USAAF guards, Franco Cargnel and Vito Procida ran unopposed among the large collection of Flying Fortresses, Liberators, Marauders, and Mitchells. As the Italian demolition experts dashed unseen from the enemy air base, it suddenly erupted into thunderous chaos amid pyres of flames. Twenty American bombers were reduced to heaps of twisted, melted metal, and a dozen more warplanes damaged.

While the dramatic raid achieved its propaganda purposes, it could not conceal the looming presence of the Allies at Italy’s southern doorstep. But propaganda is a double-edged sword. While the Americans were duped into imagining that Pantelleria had been a required objective in their conquest of the Peninsula, Italians no less regarded this Central Mediterranean ‘Gibraltar’ as an impregnable bulwark against invasion. Its capture after less than a month of resistance came as a greater shock to them than the loss of North Africa, and national morale was badly shaken.

“The fall of the island burst on the Italians like a shock of cold water,” according to Mussolini himself. “One may say that the real war began with the loss of Pantelleria. The peripheral war on the African coast was intended to avert or frustrate such an eventuality.” Remaining hopes were pinned to successful resistance on the much larger, but nearer island, although now the possibility of enemy forces setting foot on the homeland itself was considered for the first time. “With the fall of Pantelleria,” he said, “the curtain went up on the drama of Sicily.”

Privately, however, he was realistically pessimistic, if hopeful–not for Sicily–but for the outcome of a broader strategy. He considered Sicilian resistance ultimately untenable. The island, thanks to enemy air supremacy, was almost as difficult to supply as Pantelleria had been, and the topography did not lend itself to defense. He nevertheless wanted Axis forces to put up a vigorous fight for Sicily, but only to waste the Allies’ time and resources. “There is an Italian proverb,” he told his commanders, “that he who defends himself is lost. A passive defense would certainly result in that conclusion. An active defense can, on the contrary, wear out the enemy forces and convince him of the futility of his efforts … We can still keep the situation under control, provided we have a plan and the will and capacity to apply it, as well as the necessary resources. Briefly, the plan can only be this: resist on land at all costs; hold up enemy supplies by the extensive use of our sea and air forces.”