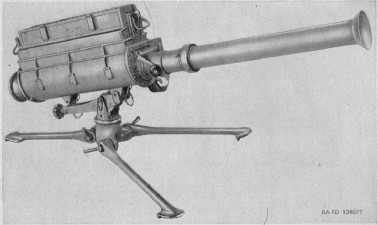

Drawings of the M-25, its rotating firing chamber and magazine. Army art

The innovative weapon quickly disappeared

In the face of increasingly powerful German tanks, the U.S. Army spent much of World War II searching for more powerful anti-tank arms. As the conflict ended, the ground combat branch had two different bazookas, as well as a recoilless rifle for infantrymen.

After the war, Army leaders tried replacing all of these weapons with a single new design. The service’s weaponeers delivered a rapid-firing, lever-action rocket launcher.

But despite being an innovative concept, the M-25 repeating rocket launcher quickly disappeared from the American arsenal. Today it’s an historical oddity.

The European Theater Board—which the Army established in 1945 in order to critique the ground combat branch’s performance against the Nazis—felt the “the bazooka had performed extremely well,” Army major Robert Doughty writes in The Evolution of U.S. Army Tactical Doctrine, 1946–76.

“A 3.5-inch bazooka had been introduced toward the end of the war to replace the 2.36-inch weapon,” Doughty adds in his official monograph.

The M-25 was a logical extension of these earlier launchers, offering a faster-firing alternative to single-shot bazookas. The new weapon even incorporated a number of features that its designers lifted straight from the 3.5-inch M-20 “Super Bazooka.”

The repeating rocket launcher had the same trigger, sights and front barrel as the single-shot M-20. Both the M-20 and M-25 could break in half for easy transport.

The quick-firing weapon M-25 also fired the exact same type of 3.5-inch ammunition as the M-20. The ground combat branch could rest easy knowing that existing stockpiles of tank-busting, smoke-generating and training rockets would not go to waste.

The biggest difference between the two designs was the M-25’s rotating firing chamber. With two flips of a handle, an infantryman could drop a fresh round into place, seal the mechanism back up and be ready to shoot.

The projectiles dropped into position from a top-mounted magazine. With all the rockets fired, a soldier could clamp on a fresh magazine or troops could open the top of the hopper to load up individual rockets.

Compared to the M-20, “loading time is greatly reduced, since a rocket may be inserted into the magazine while the weapon is being aimed and fired,” the official operator’s manual notes.

In addition, “the magazine loading feature … improves the safety of the weapon over the rear loading single shot rocket launcher, since reaching behind the launcher during the loading operation is avoided,” the handbook adds.

Unfortunately, the new launcher was also significantly beefier. The M-25 weighed almost 50 pounds—more than three times as much as the shoulder-fired M-20.

As a result, the repeating rocket launcher need a tripod to keep it stable, making it even bulkier. A single infantryman would not have been able to operate it alone.

But the weapon wasn’t any more powerful than the single-shot models. The Army quickly became confused about what to do with its new contraption.

In 1948, the Army had been blind-sided by North Korea suddenly standing up its first tank formations. The ground combat branch demanded better anti-tank weapons. But by the time the Army adopted the M-25 three years later, the threat had largely subsided.

“Due to the enemy’s lack of armor in winter operations [in] 1950–1951, this group of weapons had little decisive effect in the local fighting,” according to a Johns Hopkins University report.

We don’t know if any of the quick-shooting weapons ever actually made it to Korea.

“Since it was standardized and given an M-designation, and there were 1,500 made, I think that in all probability it saw at least limited combat testing in Korea,” says Gordon Rottman, author of The Bazooka.

But if they did occur, the experiments couldn’t save the new launcher. None of the Army’s official organizational documents ever called for the lever-action weapon to be issued to troops.

Instead, soldiers kept their lighter M-20s ready for at least another decade, with some units even taking them to Vietnam. The ground combat branch eventually replaced the shoulder-fired rockets with a combination of disposable rocket launchers and recoilless rifles.

No one seems to know exactly what happened to the remaining M-25s. But the Texas Military Forces Museum in Austin has at least one of these innovative arms in its collection, according to Rottman.