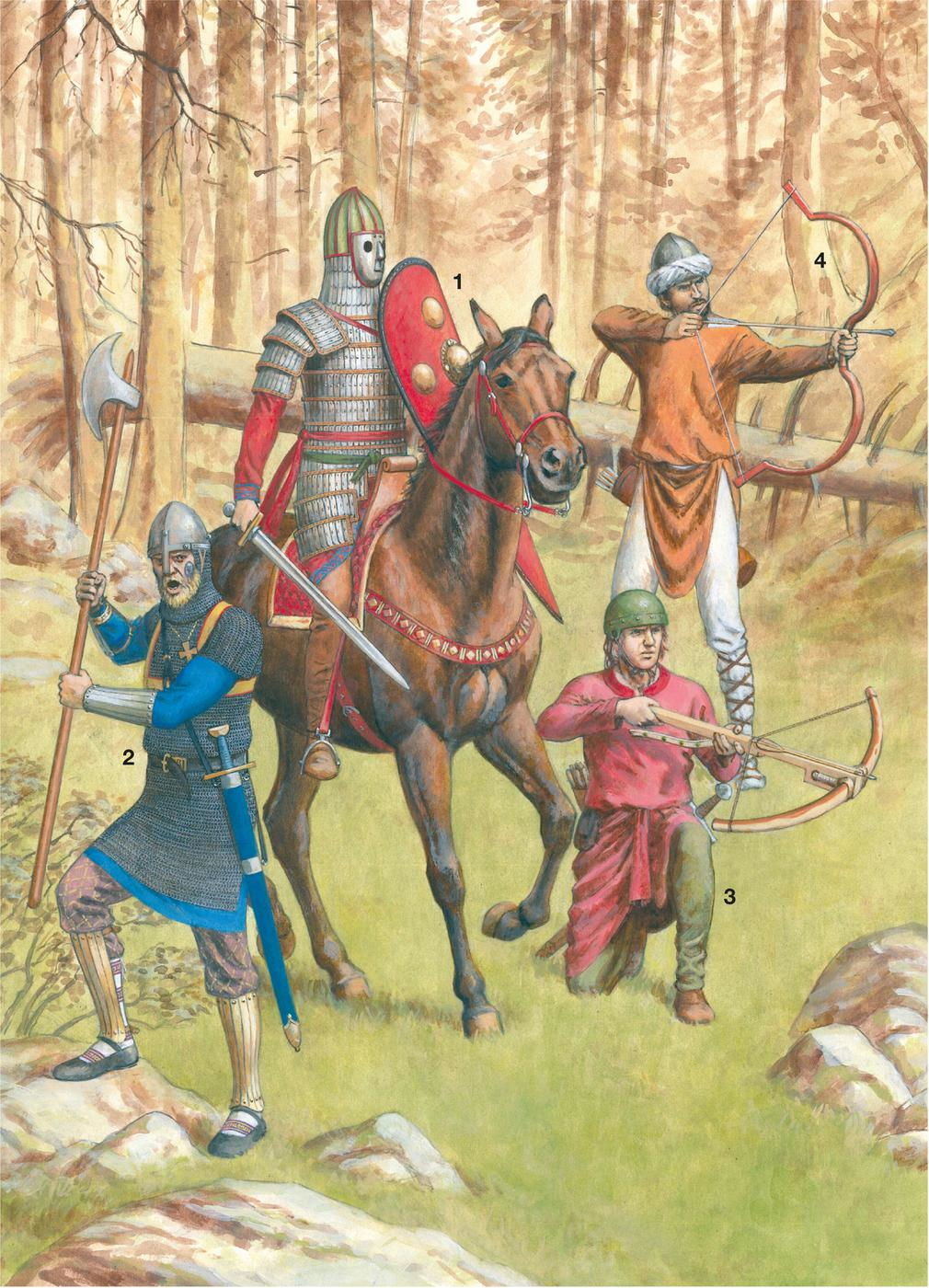

1: Norman heavy miles armatus 2: Varangian guardsman, Byzantine army 3: Norman arbelestier

4: Muslim iklīm local soldier

Opportunity came soon, and opportunity for these professional soldiers meant war. This time, however, the war was not to be another of the incessant squabbles between the Lombard states. Their employer was to be the Byzantine emperor, and the objective strategic: control of the eastern Mediterranean. The empire’s objective was no less than the reconquest of Sicily from the Muslims.

The balance of power in the central and eastern Mediterranean had been slowly shifting. The outposts and colonies in Italy that the Arabs had established during their earlier heyday had been gradually eliminated during the tenth century, while raids from Arab corsairs based in Sicily and Spain had been countered by stronger Italian defenses and even counteroffensives by Genoa, Pisa and Byzantium. Sporadic and even devastating corsair raids still occurred, but the Muslim states themselves were increasingly on the defensive, in North Africa, Sicily, as well as in Spain. In Sicily, a civil war had begun which absorbed the attention of the island’s leaders, while their overlords in Tunisia were equally preoccupied with a chaotic internal situation there. Sicily had ceased, in short, to be a major strategic threat to the Christian powers in south Italy, and was beginning to look like a strategic opportunity.

Constantinople had not yet lost the military strength and momentum that had been built up by the great line of Macedonian emperors, even though its increasingly feckless rulers were leading it into a period of corruption and decline. Aggravated into action by Arab corsair raids on coastal cities and shipping, which had sprung up again in Italy following Katapan Bojoannes’ departure, Constantinople had decided to move onto the offensive against the Muslim world around it. The power of the empire was committed to a campaign aimed at clearing the eastern Mediterranean of Muslim pirates. Victory followed victory, and in a series of highly successful campaigns by the army in Syria, and the navy along the Anatolian and North African coasts, the Byzantines succeeded in driving many of the pirates from the sea. But the pirate raids would only resume, Constantinople figured, if their home bases were not crippled as well.

The time was right, it was decided, to dust off Emperor Basil’s plan to attack the corsair ports in Sicily. Doing so could break the pirate threat, and also protect Byzantine power and sovereignty in southern Italy. Basil’s project, which had been abandoned on his untimely death, was thus revived some thirteen years later, in 1038. By late spring a great army had been raised to ravage Muslim Sicily and, if possible, bring it back under Christian rule.

Constantinople had reason to be optimistic. Sicily had been racked for several years by a major civil war, pitting one prince, or emir, Ahmad al Akhal, against his brother al Hafs. The conflict had divided the powerful local aristocracy, creating factions that struggled for power while the central administration gradually fell apart. The loss of central control in turn had allowed the Christian communities in the northeast of the island (the Val Demone), who had held to their faith during over two centuries of Muslim rule, to exercise greater freedom and seek support from potential Christian protectors in Italy and Constantinople. The Byzantines, indeed, were already taking advantage of the chaos afflicting their old enemies, and were preparing the ground for intervention through their superb intelligence systems, subtle diplomacy, and a lavish hand for buying off opponents and securing adherents. Now, secure for the moment on its eastern borders, the court at Constantinople saw that an intervention in Sicily might be successful.

Suddenly, Byzantium was presented with the ultimate tool – potential treason in the Muslim camp. No less than Emir Ahmad had invited them to invade his country. The emir had turned to Constantinople in desperation, after his army had been defeated by al Hafs. The latter’s forces had been reinforced by troops sent from the North African Zirid Emirate, who were the sovereign protectors of Sicily. Ahmad now hoped that, with the help of a Byzantine army, he could turn the tables on al Hafs and the Zirids-who were, themselves, under severe pressure from their superiors in Cairo and probably unable to send further reinforcements. But then, too late, Ahmad began to recognize the implications of his act, and realized that the Byzantines might have bigger designs than merely to help him regain his position. Dropping his planned treason, he quickly, probably desperately, tried to patch up a common Muslim front against the coming invasion. But he had miscalculated again. Al Hafs accepted the principle of a reconciliation, but not the reality, and before long had Emir Ahmad was assassinated.

Even though deprived of their traitor, the Byzantines were not deterred. Preparations for the invasion continued, and the army that was raised for the invasion of Sicily was a truly imperial enterprise. The Eastern Empire had long since abandoned the Roman concept of a citizen army, even in its Greek and Anatolian heartland, and relied instead on a professional army of trained, seasoned, and disciplined troops. But the cost of maintaining a standing army, large enough to defend the empire’s long borders against its many enemies, had become a major political issue in Constantinople -compounded by legitimate fear of the military aristocracy’s political aspirations. This meant, in practice, that an army for a distant campaign – as was the one for Sicily – was composed of a minimal core of professional soldiers, supported by more numerous local levies, mercenaries, and contingents from allies.

The core of the invasion force was composed of Greek and Bulgar soldiers from the heart of the empire, supported by the imperial navy. But the Byzantine provinces of Italy, which presumably would be the first beneficiaries of an end to Sicilian pirate activity, were heavily assessed to support the invasion force. The militias of the major southern Italian towns, which originally had been organized to defend their homes against Arab raids, were now mobilized into the invasion force. Additional troops were levied and conscripted, the local citizens were taxed to cover expenses, and the Byzantine force was further strengthened by a large and motley body of mercenaries. Most interesting of those mercenaries, perhaps, was a contingent of Scandinavians headed by Harald Sigurdson, or Harald Hardrada, a magnificent warrior who figures as one of the last great Vikings. For the previous eight years, while suffering political exile from Norway, Hardrada had employed his energy and skill in the service of the rulers of Kiev as well as of the Byzantines. His Varangian, or Russian, contingent was one of the key infantry units of the invasion force.’ Whether Hardrada and his Scandinavians found any particular affinities with their frenchified Norman cousins, also members of the invasion army, is open to conjecture.

Up to 500 Norman knights, including the Hauteville brothers William and Drogo, had joined the invasion force. When the Basileus had called upon his Lombard allies in Italy to support the invasion, Guaimar and the other princes had found it politic to agree. Guaimar, in fact, had very good reason to please Constantinople: his rival Pandulf was in the imperial capital scheming to get Byzantine support for regaining his old principality of Capua. Guaimar, by pleasing the Byzantines, could hope to neutralize Pandulf, and might even get the Basileus to recognize his own title to Capua. Moreover, with no wars with his neighbors looming, contracting out his Norman mercenaries would relieve Guaimar and his citizens of their dangerous presence – the Norman tendency to freelance raiding when not otherwise engaged having made them exasperating, expensive, even dangerous allies. On these considerations, Guaimar provided a contingent of about 300 knights to the Byzantine army.

Accompanying the Normans was a Lombard mercenary from Milan called Ardouin. Ardouin, who spoke fluent Greek, initially served in the role of intermediary or interpreter between the Greek army commanders and the Norman contingent. As the Normans apparently had no single leader of their own, however, Ardouin was able to use his position to emerge as effective spokesman for the Normans in the polyglot army.

The invasion army was led by Byzantium’s greatest living general, a character of epic proportions called George Maniakes. From Asia, possibly of Mongol origin, he was a great bear of a man: strong, ugly, thoroughly intimidating. His victories in Syria some years earlier had rescued the regime at a time of great danger, and his military prowess was much respected in the capital, but he was a blunt man who had to survive under a regime increasingly given to palace intrigue and treachery. His opposite number as commander of the Byzantine fleet was a nobody called Stephen, who unfortunately for Maniakes was-whatever the chain of command may have said -better connected to the real power behind the Byzantine throne. Stephen’s main qualification, in fact, was that he was brother-inlaw to the eunuch John Orphanotrophus, who dominated both the vacillating Empress Zoe and the man she had raised to the throne with her, Emperor Michael. Stephen the plotter and Maniakes the fighter were a bad match, but not necessarily a fatal one; the Byzantines had had much experience in handling mixed-force armies and divided commands such as the one about to invade Sicily. Indeed, the first operations went exceptionally well. After picking up the Lombard, Norman, and other Italian contingents in Salerno, the fleet carried the army across the strait from Italy to Sicily, without incident and with every hope of victory.

The invasion, even without Emir Ahmad’s assistance, was an initial success. Messina was stormed, major battles were won at Rametta and Troina, and within two years over a dozen major fortresses in the east of the island, plus the key city of Syracuse, had been subdued.’ Byzantium held the initiative and was stronger on the ground and sea. Reestablishment of Constantinople’s rule over this richest prize of the Mediterranean, with its huge grain surpluses, cotton, sugar, fruits, silks, and other luxury manufactures, was conceivable and could have changed the regional balance of power definitively.

Throughout the early victories, the Normans had distinguished themselves as useful allies and valorous warriors; according to their friendly chroniclers, they had often made a crucial difference. The Normans appeared to be part, albeit a small part, of a winning effort that might reestablish Byzantium’s preeminence in the region. Among those Normans, William of Hauteville in particular began to stand out. A competent, unassuming soldiers’ soldier, he apparently had a knack for attracting people’s trust while not making enemies. But it was as a fighter that he made his name amongst the hard men of the invading army. When he dispatched the Emir of Syracuse in single combat outside that city, he was awarded the nickname of “Ironarm” by which he would thereafter be called, in tribute to the strength of his sword hand. It was the first step in developing the leadership role from which his family would launch itself to royalty.

Great as William Hauteville’s personal successes were, the expedition itself began to lose momentum and eventually to fall apart. Pay for the auxiliaries began to slow down and even suffer major interruptions. Disputes arose over the sharing of booty, disputes serious enough, according to the chroniclers, to cause Norman disenchantment with the whole enterprise. Ardouin, according to those accounts, protested the niggardly share awarded to the valorous Normans, and the dispute reached kindling point over a horse which Ardouin had won in battle but which Maniakes had confiscated. Maniakes flew into one of his rages when his act was challenged by Ardouin, and publicly disgraced the proud Lombard by having him whipped throughout the camp. Given Maniakes’ character, the story may indeed be true, even if it is self-serving for the Normans. Whatever the reasons, the fact is that both the Norman and Scandinavian contingents, as well as Ardouin, left the army before the end of 1040. The Normans returned to Salerno and Aversa, angry, bitter, and dangerous.

The Normans emerged from the experience, not as a valued part of a victorious Byzantine army, but as resentful and mistreated employees, fully ready to even the score at some later date with the Greeks, whom they had learned to despise as treacherous and effeminate. But in addition to developing a disdain for the Greeks, the Normans had learned valuable lessons in Sicily: the land was rich, the resident Christians were potential allies, the Muslim inhabitants were divided, and both the Greeks and the Muslims could be beaten in battle. All points that could be useful, at some later date, to those ready to capitalize on them.

The expedition lost all hopes of final victory in 1041, partly because of an argument between Maniakes and Stephen. The admiral had allowed an Arab fleet to escape through the Byzantine blockade; Maniakes had publicly upbraided the admiral, even assaulted him physically. Stephen, not one to take such an insult lightly when he had important patrons in the capital, complained to his relative the eunuch John. In the plot-ridden and suspicious atmosphere of Constantinople, Maniakes’ successes counted for little, and in short order he was recalled in disgrace and imprisoned. Without his energy and skill, and without the Norman and Scandinavian mercenaries, the once glorious invasion force was left to a strategy of consolidating its gains and waiting for better days. But they never came. As it was, developments in southern Italy demanded more urgent attention.

The Sicilian expedition had backfired, as far as Byzantine rule of their Italian provinces was concerned. The heavy taxes and levies that had been necessary to raise the army, and the almost two years’ absence of the militias, had fanned the ever-present spirit of anti-Byzantine separatism among the largely Lombard-Italian populations, particularly in the coastal towns of Apulia. Several Byzantine officials had been assassinated as early as 1038, and the tension ratcheted up throughout the next year. In 1040, open revolt broke out. The katapan was assassinated, and local militias took over control of most major cities in Apulia. The leader of the Lombard insurrection, it turned out, was Marianus Argyrus, none other than the son of that Melo who had originally urged the Normans to come to Italy some twenty years earlier. His timing was good, it seemed. With much of their army off in Sicily, the Byzantines had been caught unprepared for so extensive a revolt. But an energetic and capable new katapan was quickly appointed, who was able to hold the line and even roll back some of the rebellion by the end of the year, while waiting for reinforcements from Sicily.

All this might have been a matter of indifference to the Normans in Salerno, including those just returned from Sicily, had it not been for the machinations of their old comrade in arms Ardouin. That crafty Lombard, in spite of his questionable departure from the Greek army, still had credibility with the local Byzantine authorities, and approached them upon his return to Italy for new employment. He succeeded in gaining the trust of the new katapan, and then obtaining a military command at Melfi, a small but strategically important town in Apulia, controlling a pass on the Byzantine-Beneventan frontier. Unfortunately for the Byzantines, the new job did not secure Ardouin’s gratitude, and he would prove to be a most disloyal lieutenant. Apparently still smarting from his humiliation in Sicily, and perhaps motivated as well by a touch of Lombard patriotism, he wanted to get even with the Byzantines. He began subtly, but successfully, preaching rebellion to the citizens of Melfi. Moreover, once he felt that he had the citizens ready to act, he approached the Normans to be the instruments of his vengeance.

In early 1041, Ardouin went secretly to Aversa, where he met with a group of his old Norman comrades and made them a seminal proposition. Come with me to Apulia, he urged; I can assure you control and possession of Melfi, and from there you and I can drive the Byzantines from the rich but poorly defended areas of northwestern Apulia, and even beyond. It is not hard to imagine the excitement which Ardouin’s proposal offered; by all accounts his urgings found a ready audience among the once-again underemployed young, restless, and greedy Norman knights. Nor was Prince Guaimar inclined to stop the headstrong Normans from another adventure; they had once again become a potential problem in Salerno’s lands, where their excess of energy could only result in trouble. He may have thought that the Byzantines, now having difficulties both in Sicily and Apulia, were unlikely to hold him responsible for the Normans’ escapades.

Once Gauimar agreed to release a number of knights from his service, Ardouin had little trouble in recruiting a force of 300 knights, headed by twelve chiefs. The raid was plotted and agreement reached to split any gains from the adventure evenly, with half to be shared by the Normans and half for Ardouin.

Among the twelve chiefs who would lead parties of knights on the adventure were the two elder sons of Tancred, William Ironarm and Drogo. Once again, they were ready when opportunity beckoned. Even though full ramifications of the step they were taking would not be evident for years, it was from this thinly disguised raiding party that a great kingdom grew.