As the fog thinned at Tainan Air Base, Japanese crews were sent to their planes. By 9:30 a.m., the last of 108 Navy Bettys lifted off. Escorting the bombers were 84 A6M Zeros. Among the pilots flying was Petty Officer Saburo Sakai, leading a three-ship “V” formation that included wingmen Petty Officer Second Class Kazuo Yokokawa and Petty Officer Third Class Toshiaki Honda.

After leveling off at 22,000 feet, the crews settled in for the long flight south toward the American airbases on Luzon in the Philippines. The Zero, light in weight and with no defensive armor, cruised using a measly 18 gallons of fuel per hour. The Japanese fighters would provide cover for the bombers all the way in and out, but fierce resistance was expected, and whether the fighters could fully protect the bombers was not assured.

◆ ◆ ◆

Word of the attacks at Davao and Baguio/Tuguegarao reached Brereton at 9:47 a.m. and 9:58 a.m. respectively. Shortly after 10:00 a.m. a call from General Sutherland to Brereton approved the offensive action he had earlier asked permission to begin. Brereton’s staff had already begun preparations to launch an attack against the harbor at Takao near the southern end of Formosa rather than the airfields. A significant naval installation existed there, but the harbor assets posed no immediate threat to the Philippines. Though he now had approval in hand, Brereton decided to wait for reports from the reconnaissance plane before committing his bombers. In the event no report was received, Brereton planned to attack the Japanese by late afternoon.

The P-40 patrols from Clark returned at about 10:45 a.m. and were joined before noon by 14 of the orbiting B-17s that had taken off several hours before. Rather than stagger the turnarounds, the American planes were all on the ground except for two P-40s patrolling northeast of Clark, one bomber circling north of Luzon, and the B-17 reconnaissance plane that had launched earlier for Formosa. Although the squadrons had reacted to the news from Pearl Harbor promptly, the local command failed to anticipate how vulnerable the force would become if nearly all the aircraft tried to recover and refuel at the same time.

Seven radar sets had reached the Philippines by the first week in December, but only two—one outside Manila and an SCR-270B at Iba—were in operation. Added to that shortcoming was the fact that at Eba the aircraft had to park in a line alongside the landing strip. Native landowners adjacent to the field had refused to allow the use of their land for dispersal.

◆ ◆ ◆

High above Luzon, the Japanese aircrews were certain the Americans would greet them with guns blazing. The attack force split, one group lining up on Iba Airfield, the other headed for Clark Field.

Sakai and his squadron mates continued escorting the bombers headed toward Clark Field. Crews scanned the sky for the sign of any activity, but the only fighter patrol in the air failed to appear. Minutes later, Sakai glanced down as the big air base came into view. “The sight that met us was unbelievable,” recalled Sakai. “Instead of encountering a swarm of American fighters diving at us in attack, we looked down and saw some sixty enemy bombers and fighters neatly parked along the airfield runways. They squatted there like sitting ducks.”

◆ ◆ ◆

Gathered in the operations tent at Clark Field at 12:45 p.m. were about 40 pilots and navigators waiting to be briefed on the plan to strike Formosa. Lieutenant Frank Kurtz had his portable radio with him, and the men listened as newscaster Don Bell broadcast from the top of one of Manila’s tallest buildings. Bell reported in an excited voice that big plumes of smoke were rising from Clark Field. The crewmen smiled among themselves, since the only smoke they saw was drifting skyward from the mess hall kitchen. What they did not know was Bell was correct about smoke billowing from an American installation; he was only mistaken in that the smoke was from burning aircraft and facilities being struck at nearby Iba.

A private, standing just outside the operations tent, looked up. In an awestruck voice he commented, “Look at the pretty Navy formation!”

The sound of approaching planes had everyone on the ground craning their heads skyward. “Navy, hell!,” someone yelled, “Here they come!” The men tumbled out of the tent and ran for cover toward a nearby drainage ditch.

High above the field, the Japanese bombers drifted into view, the drone of their engines rising, the formation spread in three perfectly formed “V”s.

◆ ◆ ◆

Sakai watched from behind the bombers as anti-aircraft fire erupted beneath the formation, exploding well below their altitude. He also noted a few planes taking off from the runway, but it was too late.

The Betty bombers began opening their bomb bays. “The attack was perfect,” Sakai recalled. “Long strings of bombs tumbled from the bays and dropped toward the targets…. The entire base seemed to be rising in the air with the explosions. Pieces of airplanes, hangars, and the other ground installations scattered wildly. Great fires erupted and smoke boiled upward.”

Then a second wave of Bettys released their loads, and with no opposition threatening the bombers’ safe return to Formosa, the escort fighters peeled off to attack targets of opportunity.

Sakai spotted two B-17s, yet undamaged, on the single runway that was now pocked with bomb craters. With his left hand he flipped the lever on his throttle to arm the two 20 mm cannons mounted in the wings of the Zero. Seconds later, the first bomber filled his gunsight. Sakai squeezed the trigger and cannon rounds tore through the target, then continued toward the second Flying Fortress. Both planes erupted in flames.

As he pulled away, several P-40 fighters picked their way past holes in the runway and one by one clawed their way into the air. Sakai switched to his two 7.7 mm machine guns mounted on the fuselage. He pulled around in a sweeping turn, then rolled out and accelerated toward one of the P-40s. As the plane grew in size under the gunsight, Sakai unleashed a hail of gunfire. Bullets smashed into the P-40’s canopy, which shattered, pieces of it hurling backward in the slipstream.

“The fighter seemed to stagger,” Sakai related, “then fell off and dived into the ground. Sakai pulled away, caustic fumes of cordite from his guns filling his lungs. His fuel and ammunition nearly expended, Sakai took up a heading for Formosa, while the second wave of the strike force approached Clark.

◆ ◆ ◆

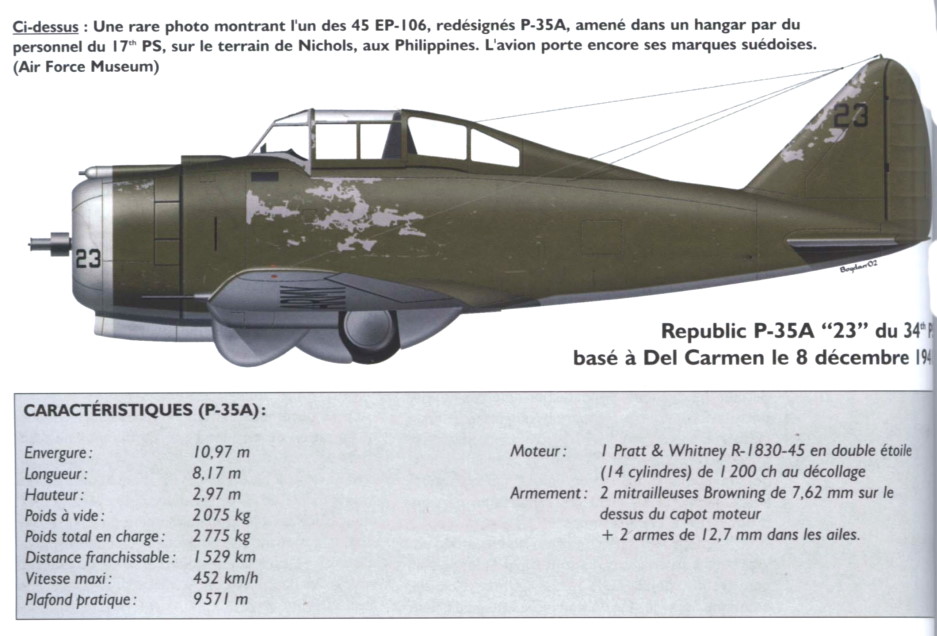

Just south of Clark at Del Carmen, pilots in the 34th Pursuit Squadron had landed their well-worn P-35As after their morning patrol. As the planes were being refueled, pilots and ground crew saw smoke billowing up over Clark. The men ran to their planes, cranked engines, and soon 16 P-35As lumbered down the dirt strip, stirring up clouds of dust as they staggered into the air.

No sooner had they retracted their landing gear than Japanese fighters pounced on them. Dogfights broke out above Del Carmen and all the way to Clark as the American planes tried to disrupt the Japanese bombing attack. Although the P-35As scored some hits, the planes were no match for the Zero, which could out-climb and out-turn its adversary, while its 20 mm cannons were superior to the two .50 cal and two .30 cal machine guns on the American planes.

No P-35As were shot down in this initial encounter, but no Japanese bombers were lost to the P-35As either. One P-35, flown by Lieutenant Stewart Robb, returned with his engine shot up, canopy shattered, and bullet holes every 18 inches along the fuselage from prop hub to rudder. Two 20 mm cannon rounds had punched gaping holes in the wings, and the right tire was blown out. Several other planes landed, damaged beyond repair.

◆ ◆ ◆

The second Japanese attacking force took up a heading for home, the airmen astounded at the ease with which they had accomplished their mission. They lost seven planes. Behind them the Americans’ airfields lay in ruins. Twelve of the B-17s at Clark had been destroyed, five others heavily damaged, along with 30 P-40s destroyed and 30 other aircraft in various states of destruction. The radar at Iba was knocked out along with most of the aircraft on the ground. Eighty servicemen were dead and 150 wounded. Inside 30 minutes, during what would later be called “Little Pearl Harbor,” MacArthur lost half his air force.

Should MacArthur have been held responsible for a decision by his flying commanders at Clark Airfield to land and refuel most of their aircraft at one time? Should General Brereton? The warnings had gone out to the flying units. The planes that had been on alert were ordered aloft along with the bombers. Was it up to the local leadership to use good judgment in how to employ and protect their assets? But regardless of where the blame lay, the deed was done, and MacArthur would have to deal with a new reality.

◆ ◆ ◆

Far to the north, the Japanese people went wild with joy over the news about Nagumo’s success at Pearl Harbor and similar words coming in from Taiwan regarding the Philippines. The radio played The Battleship March over and over. Every newspaper heralded the victories. The total material cost to the Japanese in the Philippine operation was seven A6M Zeros downed, plus one G4M Betty that crash-landed upon return to Formosa.

But aboard the Nagato, Yamamoto did not share the enthusiasm. He stayed in his cabin and wrote letters. “A military man can scarcely pride himself on having ‘smitten a sleeping enemy,’ it is more a matter of shame, simply, for the smitten.” In another letter he decried “the mindless rejoicing at home…. It makes me fear that the first blow on Tokyo will make them wilt on the spot.”

◆ ◆ ◆

Attacks from Formosa continued on a daily basis, and on 12 of December, Saburo Sakai found himself over Iba Airfield. Flak filled the air as he rolled in for a strafing run on parked P-40 aircraft. Low-angle strafe is a hazardous undertaking once the element of surprise is lost, and lost it was. Sakai ignored the peril and pressed the attack, raking two planes with gunfire from his machine guns. As he pulled off, something struck his aircraft, penetrated the cockpit and wounded him in the right leg. He made it safely back to his airfield, but there would be no more flying for the time being. It was the second time he had been wounded in action, the first having occurred during a bombing raid over his airbase at Hankow in China. He was proving himself a capable pilot, having claimed seven aircraft shot down and four more destroyed on the ground, but in some ways he was exhibiting bits of reckless behavior. Another misstep and the outcome might not be so fortunate.