Twenty-seven hundred miles west of Wake, pilots of Japan’s 11th Imperial Air Fleet based at Tainan Air Base, Formosa, passed the hours before dawn on December 8, 1941, dozing beside their aircraft. While they caught moments of fitful sleep, 4,200 miles away across the date line, both Battleship Row at Pearl Harbor and, across from it, the airstrip and hangars at Hickam Field were still engulfed in fire and explosions.

At Tainan near the southern tip of Formosa, dense fog covered the airdrome, so the planned strike could not launch until weather improved. The mission: to destroy the Allied airfields 500 statute miles away in the Philippines. Theirs was a critical segment in Japan’s plan of coordinated attacks stretching across the western span of the Pacific.

◆ ◆ ◆

One hundred miles east of Davao on Mindanao Island in the Philippines, the Japanese aircraft carrier Ryujo steamed in calm waters. As dawn broke to the east, the crews of nine A5M Claude fighters and thirteen B5N Kate dive bombers prepared for a deck launch. A smaller, airstrike later in the day by two B5Ns and three A5Ms. They accomplished little, destroying two Consolidated PBY seaplanes on the ground for the loss of one B5N and A5M.

At Davao Harbor, the U.S. destroyer-seaplane tender William B. Preston had picked up the following radio message shortly after 3:00 a.m.: “Japan started hostilities. Govern yourselves accordingly.” The order came from Admiral Thomas C. Hart, Commander in Chief Asiatic Fleet, headquartered in the Marsman Building on the Manila waterfront. All but two of the PBY Catalina amphibious planes tended by the Preston were fueled and launched on their first war patrol over the Celebes Sea.

The Preston shifted anchorage away from the two remaining Catalinas to lessen the chance of one bomb damaging both ship and planes.6 Gunners aboard the ship belted ammunition for the ship’s four .50-caliber Browning machine guns and took down the awnings which otherwise shielded the crew from the tropical sun.

◆ ◆ ◆

Among the fighter and bomber crews anxiously awaiting the order to launch from Tainan was Petty Officer Saburo Sakai, a fighter pilot who had distinguished himself in China where he had claimed four aerial victories. At age 16, Sakai had dropped out of school, then enlisted in the Navy in 1933. Basic training was brutal. Petty officers in charge beat recruits for minor infractions. Weak recruits were weeded out quickly. Sakai struggled through basic, then took the entrance exam for flight training, but failed and was assigned to the battleship Kirishima. He retook the flight exam, failed again, made another stab at it and finally passed. He and his fellow trainees continued to endure the rigorous regimen required of all candidate pilots.

Officers treated enlisted pilots with outright discrimination. This included differences in food, the availability of alcohol and cigarettes, and even the comforts in the briefing rooms where they waited before flights. Slight of build, Sakai had been toughened by the Navy training program where losers in one-on-one jousts busted out of the program and where beatings of enlisted personnel by petty officers were common.

In flight training, extensive aerial acrobatics improved strength, balance and reaction time. Exceptional vision was mandatory. The students competed to locate stars in daylight and practiced snapping their heads in other directions, then back to reacquire the star. These skills, Sakai would later cite, were the reason he rarely found himself surprised in the air and never found himself outflown. Indeed, Sakai graduated first in his class at Tsuchiura and was presented a silver watch by the Emperor himself.

To make his aircraft perform better, Sakai took things into his own hands. “The radio was useless,” he claimed. “We knew a week before the opening of the war that it was useless. It just made bunch of noise. The worst piece of equipment in the Japanese Navy was the radio for the fighter planes. You couldn’t hear anything at all.” The Japanese had not been able to isolate the heavy static in radio receivers caused by ignition of engine spark plugs.

A few days before the opening of the war, Sakai removed the radio from his plane and cut off the antenna pole to save weight. His commander, a strict disciplinarian, saw what Sakai had done and bellowed, “What did you do to this airplane?” Sakai replied, “I need to make my airplane lighter to fly to Manila.” The commander looked at the modification and barked, “Take mine out too!” As dawn approached, tension among the Japanese pilots and ground crew thickened right along with the fog. At 6:00 a.m., a loudspeaker crackled, “Attention!” What followed was the news of the successful attack on Pearl Harbor, which sent the pilots into a frenzy of celebration.

The banter was short lived, though, as one by one the pilots realized that the element of surprise would now be lost, not to mention that the Americans might be on their way to Formosa to avenge the attack on their Hawaiian fleet. Those fears were well grounded. Eighty-one P-40E Warhawks had been shipped to the Philippines in recent months bringing the total P-40 force to 107, along with elements of the 19th Bombardment Group totaling 35 B-17 Flying Fortresses.

The commander of U.S. Army Forces in the Far East, General Douglas MacArthur, considered the Philippines a prime target in the event of war with Japan, and so had placed all units on alert on November 15, over three weeks earlier. But, stopping a Japanese invasion would depend primarily on two flag officers under his command. Army Air Force planes were under Major General Lewis H. Brereton, the U.S. Army’s Far East Air Force commander with headquarters at Nielson Field, Luzon. Admiral Thomas C. Hart would command the ships and submarines of the Navy.

The nearest threat was from Japanese aircraft stationed on Formosa, but no effort was made to properly reconnoiter the island to determine where the Japanese main air assets were located. As a result, no advance planning was done to target the air bases for bombing attacks.

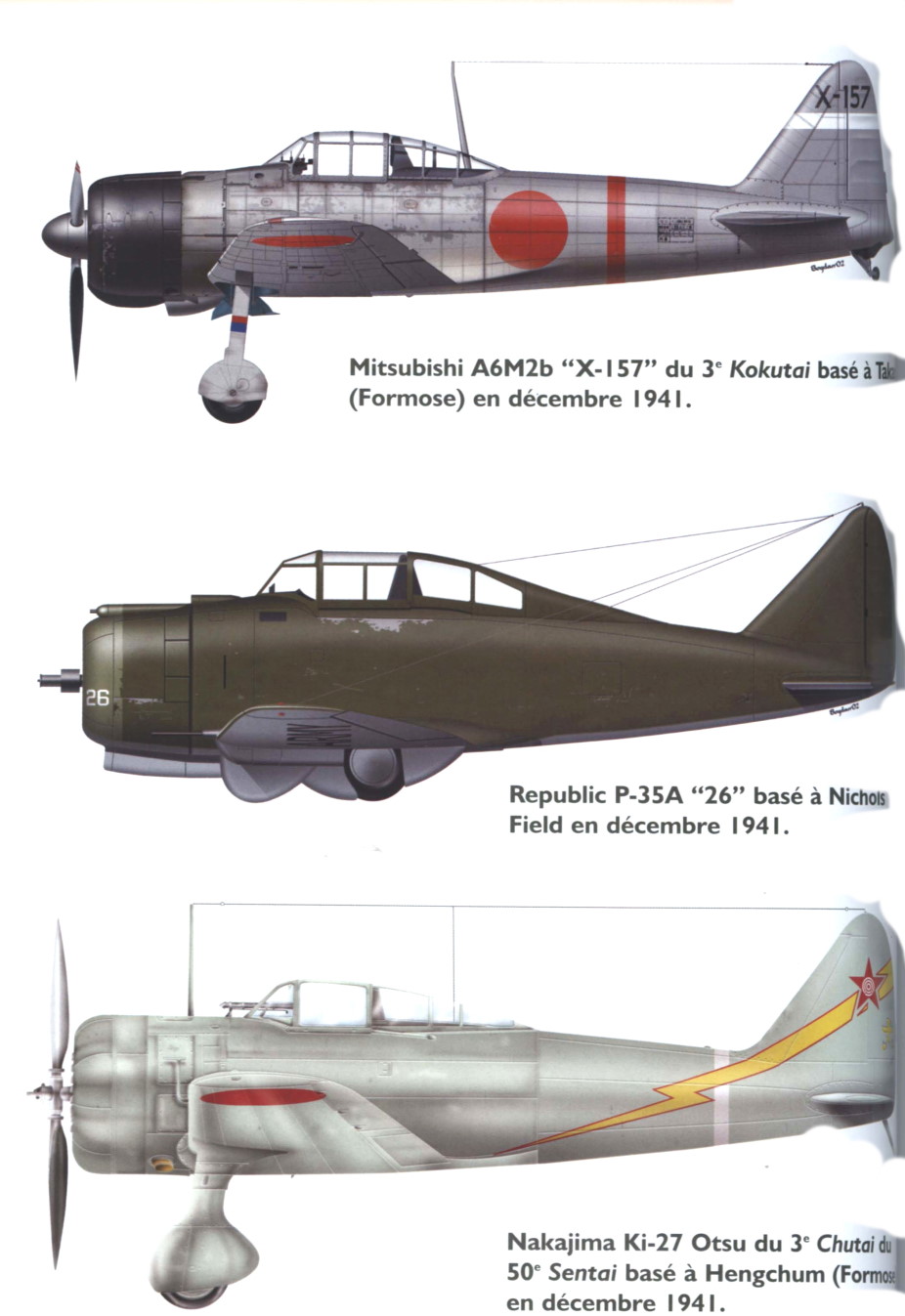

On Luzon, the 3rd Pursuit Squadron at Iba and the 17th at Nichols each had 18 P-40Es; the 20th at Clark was equipped with the same number of obsolescent P-40Bs. The 21st and 34th squadrons, respectively based at Nichols and Del Carmen fields, had arrived in the Philippines in late November but did not receive their planes until December 7, when the former was assigned approximately 18 hastily assembled P-40Es and the latter took up duties with antiquated P-35As.

Hart’s Asiatic Fleet had already begun withdrawing south on November 20, with his three cruisers and 13 destroyers already redeployed. Only his submarine force of 29 boats remained, six of them of post–World War I vintage, along with Seaplane Wing 10 and her PBY Catalina flying boats. With them were two submarine tenders, a supply ship, and several auxiliaries. The subs were armed with the Mark XIV steam torpedo, a trouble-prone weapon hurried into production by the Navy without adequate testing.

The Japanese code had not yet been fully broken, but alarming signal traffic prompted additional warning from U.S. Army Chief of Staff, General George C. Marshall, to the Philippines on November 27, 1941: “Japanese future action unpredictable but hostile action possible at any moment. If hostilities cannot, repeat cannot be avoided, the United States desires that Japan commit the first overt act. This policy should not, repeat not, be construed as restricting you to a course of action that might jeopardize your defense. Report measures taken. Should hostilities occur, you will carry out the tasks assigned in Rainbow Five the operational plan for the defense of the Philippines so far as they pertain to Japan.” This message, sent to all commands, is one of the bits of convincing evidence that President Roosevelt and his staff in Washington were well aware of the impending attack on Pearl Harbor, yet chose to allow the surprise attack in order to get the country into World War II.

There is also evidence to support the theory that President Roosevelt had for some time looked at the Philippines as bait to get America into the war as opposed to using Pearl Harbor in that role. State Department Travel Advisories had been in place since October of 1940 for Japan, China, Hong Kong, and Indochina, yet no advisory was ever promulgated for the Philippines. Though all military dependents had been withdrawn from the Philippines (and also from Guam, Midway, and Wake) in the spring of 1941, American civilians residing in the Philippines were specifically encouraged to remain in place.16 Some 10,000 expatriates resided in and around Manila and at facilities employing U.S. military personnel. Their presence offered two potential outcomes. A Japanese invasion of the Philippines would likely lead to the deaths of many Americans since they would be obliged to defend against the Japanese attack. Japan was well aware of this fact, but if the Japanese attacked anyway, it would be a cause célèbre. Roosevelt would have his pretext to declare war.

In any event, both the State Department and General MacArthur, through statements and actions, seemed focused on maintaining the belief that Japan would not open hostilities by attacking American interests in the Philippines. Regardless, the warning to the Philippines was not taken lightly.

Pursuit aircraft at Iba Field were fueled and armed, and pilots were available on 30 minutes’ notice 24 hours a day. Reconnaissance patrols were increased. All leaves were canceled. At Clark, readiness status was maintained daily. At night, eight P-40B pilots slept next to their aircraft, ready for takeoff on short notice. At Nichols Field, flying training was suspended and pilots were on one hour alert.

Major General Brereton had earlier warned his headquarters in Manila that the B-17 bombers at Clark Field were within range of Japanese bombers on Formosa. Brereton had proposed that the heavy bombers be moved to Del Monte Airbase on the southern Philippine island of Mindanao. MacArthur had agreed, but 19 of the total force of 35 were still sitting on the tarmac at Clark Field on December 8.

At 3:00 a.m. Admiral Hart had received the radio message from Admiral Kimmel in Honolulu about the raid on Pearl Harbor. Hart notified his remaining Asiatic Fleet, but he neglected to insure MacArthur had already received the same warning. Not until more than a half hour later did MacArthur get word. An enlisted signalman, who overheard the news on a California radio station to which he was tuned, passed the word to the command post duty officer. MacArthur rose from bed after a call came from Brigadier General Richard Sutherland, his chief of staff. MacArthur asked his wife Jean to bring him his bible, which he then read for a while. Then looking gray, ill, and haggard, he began to gather his staff together.

◆ ◆ ◆

With the sun fully above the horizon, 22 aircraft comprised of Japanese A-5M Claude fighters and D3A Val dive bombers roared off the deck of the Ryujo. The formation took up a heading for Davao.

An hour later, the Preston’s commanding officer, Lieutenant Commander Etheridge Grant, went forward to check progress on preparations to slip the anchor chain should it become necessary. Suddenly a lookout yelled, “Aircraft!” Grant sprinted to the bridge while Japanese planes swept around the narrow neck of land shielding Malalag Bay from the broad Gulf of Davao. The Claudes made short work of the PBYs, tied at their mooring buoys like sitting ducks. Aflame and riddled with bullet holes, the two patrol planes slipped beneath the waters of the bay as the survivors swam for shore, towing with them one dead and one wounded sailor.

During the attack, the Preston got underway and zigzagged across the bay as Japanese Vals pounced. The fleeing tender managed to evade the bombs while bringing down one of the dive bombers. The ship emerged from the attack unscathed and returned to the bay to pick up the survivors from the two lost planes.

◆ ◆ ◆

Fog was not a problem at Imperial Japanese Army fields at Heito and Kato, so at dawn, 14 G4M3 Betty bombers from Heito took off along with 18 light bombers from Kato. To the men who flew the Betty bombers, the airplane was unofficially called the Hamaki, Japanese for cigar, given the airplane’s rotund, cigar-shaped fuselage.

◆ ◆ ◆

A little before 4:00 a.m., a call from MacArthur’s chief of staff, Brigadier General Richard Sutherland, relayed word of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor to Brereton at Nielson Field. Brereton sought permission to launch an immediate air strike against the Japanese air bases on Formosa, though no aerial photos of the airfields existed, and the available maps were outdated. Sutherland took the call and told Brereton to go ahead with preparations but to wait for approval from MacArthur, who was in conference. While Brereton waited for MacArthur’s response, one B-17 from Clark Field was ordered to conduct a reconnaissance flight over Formosa. The plane’s bombs had to be downloaded before cameras could be installed in the bomb bay. P-40 fighters from Clark and the nearby Iba Air Base on the West Coast were sent aloft at about 8:00 a.m. when the radar station at Eba picked up inbound targets coming from Formosa. A half hour later, 15 bomb-laden B-17s at Clark lumbered into the air and began orbiting over Luzon.

At around 8:30 a.m. the first Japanese attacks on Luzon occurred at Baguio, where the bombers from Heito struck military barracks, and at Tuguegarao Airfield in north-central Luzon, where the Kato force struck.