Having provided us with Clausewitz, Germany supplied an antidote in the guise of Wilhelm Stieber (1818–92). Not from Prussia himself, Stieber was born in Merseburg, Saxony, and had an English mother named Daisy who claimed descent from Oliver Cromwell. In 1820 the family moved to Berlin where his father held a position in the church. Naturally enough, Stieber was also expected to enter the church and so his father paid for him to study theology at Berlin University. While there he became interested in the case of a young Swedish janitor who had been accused of burglary. In those days anyone could defend an accused person in court. So, believing him innocent, Stieber took up the case and won the Swede’s acquittal.

This first taste of legal process opened Stieber to the possibility of a future outside the church. While his father continued to subsidize his studies, Stieber secretly began taking courses in law, public finance and administration. When Stieber eventually revealed his preference for a career in law, his father all but disowned him. Stieber was thrown out of the family home and his funds were cut off. This was a pivotal moment in the young man’s career. To continue with his studies, Stieber needed an income.

This necessity led him to work as a secretary to the criminal court and Berlin Police Department. Through this vocation Stieber was introduced to the work of Berlin police inspectors, who occasionally took him on arrests. He was immediately hooked on criminal investigation, so, after graduating as a junior barrister in 1844, Stieber applied for and was granted a place as a Berlin police inspector. He was quickly given a chance to impress. The Minister of the Interior asked for Stieber to be sent undercover into Silesia to conduct an investigation into an alleged ‘workers’ conspiracy’. Posing as a landscape artist named Schmidt, he quickly identified the ringleaders of the so-called ‘Silesian Weavers’ Uprising’ (4–6 June 1844) and under orders from Berlin had them rounded up and arrested.

However, it was during the riots of 1848 – the year of revolutions – when Stieber really came to the fore. With Berlin on the verge of rebellion, King Friedrich Wilhelm IV (ruled 1840–61) rode out onto the streets of the capital in an attempt to calm his subjects. He was quickly surrounded by an unruly mob and appeared in danger of being pushed from his mount. There are many different versions of what happened next, but Stieber’s memoirs recall how he seized a banner from one of the protestors and stood in front of the king’s horse, making a path through the crowd for him to pass. Shouting ‘The King is on your side – Make way for your King!’ Stieber managed to get the king back to the palace gates where the guards carried him to safety. In some accounts Stieber is said to have arranged the whole thing as a stunt to gain popularity with the king. Stieber claims the man he saved was in fact an actor posing as the Prussian monarch. Whatever the truth, the event certainly brought Stieber into the spotlight. When in November 1850 the notorious revolutionary Gottfried Kinkel was sprung from jail, a section known as the ‘Criminal Police’ was formed with cross-district jurisdiction – Stieber was its commander.

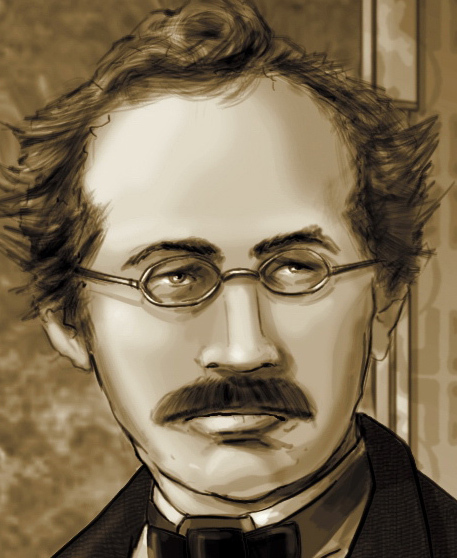

More significant was the king’s approval of Stieber’s assignment to monitor German communists attending the international industrial exhibition at London’s Crystal Palace in October 1851. Stieber travelled to London again using the alias of Schmidt, but this time posing as a newspaper editor covering the exhibition. Enjoying the right to freedom of speech and assembly in the liberal British capital, a German newspaper editor named Karl Marx had been organizing an ‘International Communist League’. Stieber went to visit Marx, claiming to be carrying family news to a fictitious colleague, Friedrich Herzog, who was believed to be a member of the Communist League. Unsurprisingly, Marx had never heard of Herzog and unwisely told Stieber to consult with a German named Dietz who held records of the communist movement.

Before Stieber went looking for Dietz he chatted to Marx for a while. Talking of his own background, he told Marx he had studied medicine and was editor of a Berlin medical publication. On learning he had a medical background, Marx asked Stieber if he knew a good cure for haemorrhoids. He went on to say that it would be impossible for him to sit and write except for a medication made up by Dietz, himself a former apothecary. Confirming this was the same Dietz holding the League’s records, a plan hatched in Stieber’s mind. Bidding farewell to Marx he went to Dietz’s address, but not before forging Marx’s signature on a note reading: ‘Please bring me some medication and the files at once.’ Posing as a physician named Dr Schmidt, Stieber duped Dietz into handing over four volumes of information on the Communist League’s activities across the globe.

From London Stieber travelled to Paris where the communists appeared strongest and best organized. A few days after arriving, a man turned up in his apartment calling himself Cherval. He was a communist and had been sent to retrieve the stolen records. When Stieber refused to hand them over, Cherval drew a dagger and attacked him. Knocking his assailant unconscious with a chair, Stieber handcuffed him and interrogated him. Cherval was in fact a German who had adopted a French name on arriving in the country. Stieber promised to drop the charges relating to his attack if Cherval would spill the beans on his co-conspirators. The communist obliged and a number of significant arrests were made.

Returning to Germany, Stieber’s information led to yet more members of the Communist League being arrested. In reward for his efforts, in January 1853 Stieber was made director of the Security Division at Berlin. Thereafter he embarked on a number of police-related cases which are outside the scope of this study except in one respect. Through his investigations he became fascinated with the world of high-class prostitutes and their rich clientele, who were often high-ranking officers and members of government. He quickly realized that these men would be extremely vulnerable if the prostitutes were agents of a foreign power:

To my amazement, I discovered that among the prostitutes who frequented these brothels, there were actually many who had acquired a certain amount of education through their constant association with their highly-placed visitors, so they could recite lines by Virgil and Horace and often commanded an entire catalogue of legal and military concepts; and to my horror, found among them women who appeared to have been predestined to become spies… Some of them had already made a regular business out of enticing intimate, compromising information out of married men in the highest reaches of society and then extorting large sums of money from them by threatening to reveal these secrets to their wives.

Thinking it best to have these women on his side, to win them over Stieber helped establish a ‘Prostitutes Recovery Fund’. The whole vice trade became much more regulated and in return for his favour, prostitutes began to supply Stieber’s officers with information relating to crimes. Before long they had became the best police spies in the city.

Everything was going well for Stieber until 1857, when the king was declared insane after suffering a brain tumour. The throne passed to a regent, the king’s liberal-minded brother Wilhelm. With his royal protector out of the picture, Stieber’s many enemies had him imprisoned and ransacked his apartments looking for documents that might compromise their own positions. Unfortunately for them Stieber escaped from his cell and rescued the documents, which he knew would save his neck. Arguing his case in public through the newspapers, Stieber claimed that to accuse him of wrongdoing was to accuse the king himself. His accusers quickly drew a line under the business and Stieber was largely exonerated, albeit left without an appointment and put on half pay.

Continuing his work against communists and anarchists, Stieber went to St Petersburg. With him he took his dossiers on Russian revolutionaries working abroad in London and Paris. Arriving at a time when the Russian secret services were at an embryonic stage, Stieber was asked for advice on dealing with radicals living abroad. Stieber’s solution was to track down ex-pat Russian criminals, forgers and blackmailers and, in return for immunity from prosecution, these would be paid to spy on the radicals.

But Prussia was never far from Stieber’s mind. His rehabilitation came when in 1863 he uncovered a plot to assassinate the newly appointed Prussian prime minister, Otto von Bismarck (1815–98). He was introduced to Bismarck by August Brass, founder of the Norddeutsche Allgemeine Zeitung, who recommended him despite his unpopularity. The plot may have been a ruse on Stieber’s part, but Bismarck took it seriously enough. An assassination attempt was indeed attempted by a Russian revolutionary named Bakunin, but with the benefit of hindsight it does appear a somewhat stage-managed affair. Bakunin ended up shooting a dummy of Bismarck, and Stieber’s men were miraculously right on hand to arrest him. Charges were not pressed against the Russian, who was quietly slipped out of Prussia never to return. Stunt or not, Bismarck was impressed and from that moment, Stieber became his chief problem-solver.

Bismarck set a special mission for Stieber, one far more important than any he had thus far attempted. Bismarck’s greatest legacy would be the unification of the independent German states into a single political entity – Germany. However, at the time these independent German states looked to Austria for leadership rather than Prussia. Before any unification could take place, there would have to be a showdown with Austria. Bismarck wanted Stieber to observe and report upon Austria’s military preparedness.

The most commonly told story about Stieber is that, following Bismarck’s request, he went into Austria disguised as a harmless pedlar. By day he rode from village to village selling religious statuettes; at night he frequented inns, discretely selling pornographic cartoons to drinkers. Months later, having toured the country and built up maps of the military defences and stores, he returned to Berlin to make his report. So accurate were his findings that Bismarck and General von Moltke were able to confidently plan a lightning campaign which saw Austria defeated in seven weeks.

The story is a good yarn and is perhaps based on some elements of truth. However, it grossly over simplifies the true scale of Stieber’s operations and downplays his true genius, which was the organization of intelligence gathering. After asking him to spy on Austria, Bismarck gave Stieber ten days to formulate a plan for establishing a network of spies there. Undaunted by the scale of the task, Stieber applied the same patient methodology common in police detective work to military espionage.

Through analyzing past methods, Stieber realized that traditional methods of espionage had produced only limited results. Amateur spies did not have the technical knowledge to collect intelligence of real relevance. Also, in previous wars only small numbers of spies had been employed, making it easier for enemy counter-espionage services to concentrate their resources and pick them up or to feed them false intelligence. Stieber wanted to flood Austria with an ‘army’ of observers, draining police resources to the point where surveillance became unfeasible. If a single agent was caught they would know almost nothing about the other spies and even if several were caught they would have so little idea of the grand scheme of things that the damage would be negligible.

Austria would be divided into districts, each with a ‘home base’ set up and controlled by a ‘resident spy’. To avoid suspicion, ‘resident spies’ would not be foreigners, but natives of the district. Their districts would also be quite small so they would not have to make any unusual travel which might be noticed. Their first duty would be to recruit a network of informers throughout their assigned district and collect their reports. These reports would be sent to a central headquarters in Prussia where they would be assessed. Always kept up to date, the processed data would be passed on to the appropriate political or military authorities, enabling them to respond accordingly. However, when very important information came in from the resident spies, special agents would be sent into Austria to investigate it further. With the groundwork already done by resident spies, the job of these special agents would be much easier.

Wherever possible Stieber wanted the ‘resident spies’ to be recruited from among local journalists. If this was not possible, then the resident spy was to attempt to at least use journalists among his informants. While generals in the Crimean and American Civil Wars had been frustrated by the interference of the press, Stieber had recognized how powerful journalists were becoming and how they had a right to ask questions without causing suspicion. Through their profession they would have already made contacts in government and military circles – contacts that were like a tap waiting to be turned on. But why would normally reputable journalists spy for Prussia? Stieber knew that the weak point of most journalists was that they were always short of cash.

Bismarck approved of the plan and went one step further, allowing Stieber to form a Press Bureau. The king had already expressed concern how the London-based Reuter’s Telegraph Company had a monopoly on the news and as such controlled public opinion. He wanted a Prussian news service and so Stieber entered the perhaps yet murkier world of news management.

The observation service began in Austria under cover of ‘press activities’. One immediate problem was in funding the rapidly growing network of spies. In solving this issue, Bismarck proved himself as wily as Stieber, telling him to recruit captured forgers and counterfeiters from Berlin prisons. They were careful not to print so much Austrian money the economy would be destabilized, but just enough for funding never to be a problem.

With Austrian counter-espionage duties handed over to inept, retired police officers, Stieber’s agents were able to uncover a great deal of important facts, namely:

• Austria also desired a united Germany, with a federation of states and them at the head. They believed this was achievable partly because most of the independent German states were, like them, Catholic, while Prussia was largely Protestant.

• Austria did not expect a war and was totally unprepared for one.

• The Austrian people were against war.

• Austria would take two weeks longer than Prussia to mobilize its armies.

• Austrian weapons were outdated and no match for the new Prussian ‘needle guns’.

Armed with these facts, Bismarck asked Stieber to stir up the Austrian population by spreading false stories in the Austrian press. The idea was to make the Austrian government so unpopular at home that it provoked them into declaring war on Prussia. At the same time, Bismarck asked Stieber to stir up trouble among the many different ethnic groups in the Austrian empire. Stieber hired 800 agitators from among Czech and Slovak dissidents who would start uprisings in Hungary, Dalmatia and Moravia should war be declared. He also made plans for a ‘Hungarian Freedom Legion’ made up of Austrian army deserters who would attempt to break Hungary away from Austria.