If the three pillars of the medieval state comprised God, Pope and King, the Renaissance prince was a subtly different character from his forebears. Cunning and ruthlessness were expected, inspiration coming more from Machiavelli than Malory. James IV (1488–1513) was, in some ways, the mirror of the Renaissance ruler. He was cultured and learned, his interests eclectic: building and the arts, medicine and science (he was known to practise dentistry upon his courtiers). At the same time, he was romantically attached to the cult of chivalry. The founding of a Scots Royal Navy became one of his grandest passions. He was married to Henry VII of England’s daughter Margaret, thus Henry VIII became his brother-in-law. Both men had a yearning to strut upon the European stage, and tension escalated in 1513 when Henry was contemplating an expedition against France in support of the Holy See and the Emperor Maximilian.

James was placed in the invidious position of having to choose an ally, to continue sitting on the fence was politically unsustainable. The King of Scots chose to support the traditional friendship with France, and a series of ultimata delivered to Henry earned nothing but derision. This created the strategic backdrop to the Scots campaign in North Northumberland, one which was succeeding admirably in its key objective of diverting English forces from the Continent, till James took the fatal decision to fight at Flodden. This battle, fought on 9 September, was an unparalleled disaster. The Scottish army was outfought and suffered grievous loss, the cull falling heaviest on magnates and gentry. Slashed and hacked by bills, an arrow shot through his jaw, one hand virtually severed, James IV lay unnoticed among the piles of corpses.

A REVOLUTION IN SHIPBUILDING

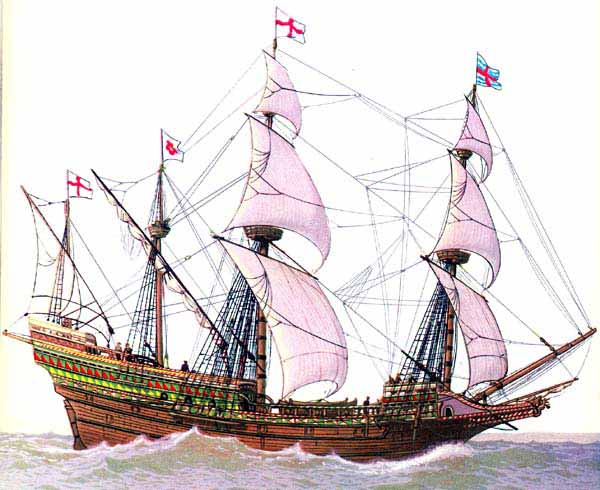

In the course of the sixteenth century, warship design and construction underwent a significant revolution. Northern round ships or carracks, with a length twice the beam, were being built up to a weight of 1,000 tons. The fact that these ships were constructed as floating gun platforms brought out the final transition from converted merchantman to purpose-built man-of-war. They were multi-masted, multi-sailed and had sufficient weight to carry soaring timber castles, bearing an increased weight of ordnance. Both James IV and Henry VIII competed in a naval arms race in the early years of the sixteenth century. The ship which was to become most closely identified with Tudor navies was the race-built galleon. Sleeker and swifter than the carrack, two or two and a half times as long as it was broad, the height of the superstructures was reduced to produce a faster and more seaworthy vessel.

A passionate debate as to the best suited of these types for naval use raged throughout most of the century. More conservative-minded captains favoured the solid bulk of the grand-carrack. In close combat these enjoyed significant advantages. The castles provided excellent and lofty gun platforms, light pivot guns, hand guns and bows could shoot directly down onto the enemy deck and shooters enjoyed good protection. Even if she were boarded, the carrack’s defenders could maintain their position in the castles, making life distinctly uncomfortable for attackers. The crucial advantage enjoyed by the galleon was her superior sailing qualities. She could stand off and use her guns to batter the heavy carrack at a distance. The Spanish, whose ships were effectively floating forts, favoured the carrack, a castle on the waves.

By the end of the century, Revenge was regarded as a fine example of the race-built galleon. Her gun deck was around 100 feet, with a total length of about 120 feet. She was 32 foot across the beam, and her main ordnance was a score of truck-mounted culverins. Fixed firing platforms had now given way to a two-wheeled timber frame carrying guns with a barrel length of some 12 feet. As yet there was still no standardisation of calibres but the gun threw an 18-pound ball. The ships were all twin-deckers, and these heavier pieces were carried on the lower level while, on the upper, was mounted a further battery of smaller guns firing 10-pound shot. Ships of this period were crammed with ordnance, and the vessel could also house a dozen or more small muzzle-loaders (‘murderers’) throwing a 2-pound ball, earlier breech-loaders having now been phased out.

This general lack of standardisation was the curse of naval gunnery. Several times, during intense bouts of fighting in the course of the Armada battles in 1588, the English were rendered impotent for want of shot. Bruising and effective as the galleons’ fire proved against cumbersome carracks, the capital ships survived, though not without loss and considerable damage. Galleons, in order to keep the weight as low as possible, were built with the lower gun deck stepped down at rear to create a mezzanine type effect. This housed the two hindmost guns, which could be swung around as stern-chasers should circumstances dictate. Officers enjoyed elevated quarters, while the mariners were accommodated on the gun deck. Ships were also fitted with an ‘orlop’ deck: a further mezzanine, a couple of yards or so above the planking, which formed the quarters for the specialists on board, carpenter, surgeon and purser. In all, the vessel would require a crew of around 150, of whom 70 might be marines with 30-odd gunners.

Though Sir Richard Grenville’s epic stand on the shot-torn decks of Revenge is not a Scottish fight, Sir Walter Raleigh, in his subsequent report, gives a vivid impression of the conditions which obtained in sea-battles of this era:

All the powder of the ‘Revenge’ to the last barrel was now spent, all her pikes broken, forty of her best men slain, and the most part of the rest hurt. In the beginning of the fight she had but one hundred free from sickness, and fourscore and ten sick, laid in hold upon the ballast. A small troop to man such a ship, and a weak garrison to resist so mighty an Army. By those hundred all was sustained, the volleys, boardings, and enterings of fifteen ships of war, besides those which beat her at large. On the contrary the Spanish were always supplied with soldiers brought from every squadron: all manner of arms and powder at will. To ours there remained no comfort at all, no hope, no supply either of ships, men or weapons; the masts all beaten overboard, all her tackle cut asunder, her upper work altogether razed, and in effect she was evened with the water, only the very foundation or bottom of a ship, nothing being left over head either for flight of defence.

RESTLESS NATIVES

When James IV finally embarked upon the abolition of the Lordship in 1493, he doubtless contemplated the move as enabling him to cement royal power in the west. In this he was mistaken. The fall of Clan Donald ushered in an age, not of centralised authority but of murderous, internecine strife, the Lin na Creach (‘Age of Forays’). In the same year he kicked away the last supports of the tottering Macdonald hegemony in the west, James’s Parliament enacted that all coastal burghs should provide a well-founded vessel of not less than 20 tons with able-bodied mariners for her crew. To reinforce awareness that the ending of Clan Donald’s sway was but the beginning of a new extension of the business of the state, James led a fleet to the Isles in August, accompanied by Chancellor Angus and a fine train of magnates. At Dunstaffnage, where he stayed a mere 11 days, he may have accepted the surrender of some chiefs, reaffirming their holdings by royal charter. The Macdonalds were not completely over-reached; both Alexander of Lochalsh and John of Islay received knighthoods.

In 1495, accompanied by Andrew Wood and commanding Yellow Carvel and Flower, James cruised down the Firth of Lorn, through the Sound of Mull to MacIan of Ardnamurchan’s seat, Mingary Castle, where a quartet of powerful magnates bent their collective knee. These included such noted seafarers and pirates as MacNeil of Barra and Maclean of Duart. While James was diverted by his flirtation with the posturing Perkin Warbeck, this policy of treating with the chiefs was undone, largely by the avarice of Argyll, who preferred force to reason. Inevitably, this merely served to alienate the Islesmen, whose galleys conferred both force and mobility. In 1496, Bute had been taken up and disorders reached a level where the king felt obliged, once again, to assert his authority by launching a naval expedition. Indeed this was the only means whereby the chiefs could effectively be brought into line. A land-based expedition would accomplish nothing; Islesmen counted wealth and power in the number of their keels.

The king’s expedition of 1498 proceeded by way of Arran to his royal castles of Kilkerran, where he spent two months, and Tarbert. James, though he wished to impress his authority on the west, did not necessarily have much enthusiasm for the chore. For the royal writ to run in the west and to fill the gap in authority left by the collapse of the Lordship, power needed to be exercised by loyal and respected subordinates. Argyll had succeeded in alienating a number of the chiefs, including his own brother-in-law, Torquil MacLeod of Lewis, who was to become a fierce opponent. MacLeod had secured, by uncertain means, the keeping of the boy, Donald Dubh, would-be claimant to the defunct Lordship. Argyll was no more loved by Huntly, his successor as Lieutenant in the north-west and one who proved equally hungry for personal gain.

James was briefly diverted in 1501 by the near-fiasco of his Danish adventure and did not turn his gaze westwards again until the following year. That Torquil MacLeod should control the person of Donald Dubh was fraught with risk. MacLeod was summoned to appear, failed to do so and was outlawed as a consequence. Huntly was commissioned to take up Torquil’s confiscated estates, doubtless to Argyll’s fury, he being sidelined for failing to keep a grip on his own kinsman. Both Mackintosh and Mackenzie managed to escape from confinement, though the first was soon recaptured and the second killed. By 1503, disturbances had become widespread, and Huntly was engaged in wholesale dispossession of those who refused to submit. With Donald Dubh lending legitimacy to their cause (old John of the Isles died in January 1504), the rebels under Torquil struck back. Bute was again extensively despoiled.

Parliament, sitting in March 1504, commissioned Huntly to retrieve Eilean Donan and Strome castles, while a naval command, assembled under the ever vigilant eye of Sir Andrew Wood, was entrusted to Arran. The fleet was to reduce the rebels’ stronghold of Cairn na Burgh, west of Mull in the Isles of Treshnish. The capital ships, with a full complement of ordnance, soon proved their worth; naval gunnery swiftly reduced Cairn na Burgh. Few details of the siege have survived, but the operation would clearly have been a difficult one. The ships would come in as close as the waters permitted and deliver regular broadsides, essentially floating batteries. What weight of shot the rebels possessed is unclear; most likely it was not very great. Several rebel chiefs – Maclean of Lochbuie, MacQuarrie of Ulva and MacNeil of Barra – presently found themselves in irons. Gradually the power and authority of the crown was restored. These captured chiefs saw little prospect in continued defiance. Argyll was fully abetted by MacIan of Ardnamurchan, a ruthlessly effective pairing.

Argyll, now restored to his Lieutenancy, was prepared to be more diplomatic and, from 1506, there was a return to a more conciliatory policy, rewarding those chiefs prepared to submit, even some of those who’d been implicated or involved in the recent disturbances. MacIan too did well enough, though he had few friends in the Isles and his own advancement had to be checked to avoid the greater alienation of others, especially the Macleans. Torquil Macleod kept the rebel flame firmly alight, and his example helped to inspire dissidents. The Parliament summoned for early 1506 convicted him of treason. An expedition sent against him was to be led by Huntly and involved the hire of captains such as John Smollett and William Brownhill, with ordnance supplied from the royal train. The king and his advisors had planned on a campaign of two months’ duration to wrest Lewis from Macleod. In September, the king paid a sum of £30 to Thomas Hathowy as a fee for the hire of Raven, which had been engaged for service in the campaign. By September, it also seems likely that Huntly had succeeded in reducing Stornoway Castle and capturing Donald Dubh, though the wily MacLeod slipped the net and remained a fugitive until his death in 1511.

By now James IV was losing interest in the Isles. Control was best exercised through local magnates like Argyll, even if the Campbells, for all their avarice, were not possessed of an effective fleet of galleys. This deficiency was partly corrected by the cordial relations the earl enjoyed with the Macleans, anxious to see the ruin of Clan Donald fully accomplished in order that they might assume the mantle of a naval power among the clans. James had by now set his heart upon, and his mind towards, the creation of a Scottish national navy. In August 1506, he’d written to the King of France intimating that this naval project was a key objective. Scotland was a small kingdom, disturbed by the fissiparous tendencies of the Islesmen and magnatial factions. It was also a poor nation, lacking the resources of England. Nonetheless, during his reign, James bought, built or acquired as prizes taken by his buccaneering captains, nearly two score of capital ships, a very considerable total for the day.

TOWARDS A SCOTTISH NAVY

This proposed Scottish Navy was not a complete innovation. The king’s predecessors had been possessed of ships; as early as 1457 Bishop Kennedy of St Andrews owned the impressive Salvator – at 500 tons a very large vessel. Developments in naval architecture, influenced by advances in the science of gunnery, had necessitated the final differentiation between ships of war and merchantmen. The crown could no longer count upon assembling an effective fleet by hiring in merchant vessels and converting them to temporary service as men-of-war. Nations that sought to strut upon the wider stage required a navy as a tool of aggressive policy and a statement of intent. The fifteenth century had not witnessed any serious English interference before 1481–1482, and the prime consideration, in terms of sea power, was to protect Scottish ships against the unwelcome attention of privateers, for the most part English, who infested the North Sea like hungry sharks.

Richard of Gloucester’s campaigns showed how exposed the Firth of Forth and indeed the whole of the east coast were to a planned attack from the sea. Here, in the east, the problem was wholly different from that of the west. No Hebridean galleys disturbed the peace, but the Forth and Edinburgh were horribly exposed to English hostility. While Henry VII proved less inclined to attack Scotland than his despised predecessor and actually ran down the navy he’d acquired, the Perkin Warbeck crisis of 1497 highlighted the continuing exposure. Even when a more cordial atmosphere prevailed, the activities of privateers continued regardless; Andrew Wood and the Bartons persisted in their piratical activities as did their English opposites.

In 1491, the Scots Parliament empowered John Dundas to erect a fort on the strategically sited rock of Inchgarvie. Wood had already thrown up a defensive work at Largo. Conversely, the legislature had previously ordered the slighting of Dunbar Castle, the English occupation being the requisite spur (later, after 1497, the ubiquitous Wood was to oversee its rebuilding). Such defensive measures and the encouragement of privateers like Sir Andrew and the Bartons were entirely sound but, of themselves, insufficient to undertake coastal defence and the wider protection of the sea lanes. For this greater task, only a fleet would suffice. With James the creation of a navy rapidly rose to become a near-obsession; policy was overlaid with prestige. For the first ten years of his quarter-century reign, James spent under £1,500 Scots in total on his ships, a very modest outlay. This climbed to something in the order of £5,000 per annum after 1505, and by the end of the reign he was spending over £8,000 per annum on his new navy. To give a comparison, during the years he was on the throne, the king’s income roughly trebled but his expenditure on the navy increased sixty fold!

A switch of emphasis from west to east characterised James’s policy towards ships and shipbuilding. Dumbarton remained both as a base and a shipyard, but he considerably improved the facilities of Leith’s existing dockyards, constructed a new yard at the New Haven (Newhaven) and, latterly, another at the Pool of Airth. Not only did Scotland lack adequate facilities for the construction of larger men-o’-war, but she lacked the requisite craftsmen and these had to be imported, primarily from France. In November 1502, the Treasurer’s accounts reveal the hire of a French shipwright, John Lorans, working at Leith under the direction of Robert Barton. This first importation was soon complemented by others. Jennen Diew and then Jacques Terrell were engaged and, due to a shortage of hardwood, obliged to source timber for their new keels abroad. In June 1506, the great ship Margaret (named after the king’s Tudor consort) slid into the placid waters of the Forth. This vessel was a source of great pride to the king – as indeed she might be, the cost of her construction had gobbled up a quarter of a whole year’s royal revenue. She was four-masted, weighed some 600 or 700 tons and bristled with ordnance. James’s chivalric obsession with the panoply of war found a natural outlet in the building of his great ships. He appointed himself Grand Admiral of the Fleet and dined aboard the Margaret, wearing the gold chain and whistle of his new office.

The fiasco of the Danish expedition in 1502 acted as a further spur towards creating a purpose-built navy. This botched intermeddling represented an attempt by James, at least in part, to establish himself and his realm as a player on the wider European stage. The result was scarcely encouraging and, despite the ‘spin’ placed upon the outcome, the affair proved something of a debacle. In 1501–1502, King Hans of Denmark found he was confronted by rebellious subjects in his client territories of Norway and Sweden and had lost control of a swathe of key bastions, including the strategically significant hold of Askerhus near Oslo. James was bound to the Danes by earlier treaty, and the situation raised possibilities for a decisive intervention by the Scots. The king hurried to make preparations for an expedition: Eagle and Towaich were made ready, together with Douglas and Christopher. The total cost of the fleet and accompanying troops was a whopping £12,000, and the burden fell on the Scottish taxpayers. From the start there were difficulties. Lord George Seton had been paid to make ready his vessel Eagle, but his part ended in acrimonious litigation and impounding of the ship, which does not ever appear to have weighed anchor. Raising the requisite number of infantry, ready to serve in the proposed campaign, proved arduous; far from the number of 10,000 postulated, it seems unlikely that the force amounted to more than a fifth of that total.

When the truncated fleet finally sailed towards the latter part of May, 1502 it comprised Douglas, Towaich, Christopher, together (possibly) with Jacat and Trinity, under the flag of Alexander, Lord Hume, wily borderer and chamberlain. In the two months of campaigning, little was in reality, achieved. The Scots likely suffered loss in an abortive escalade of Askerhus. Others sat down before Bahus and Elvsborg. A significant number simply deserted. For James, who’d had equal difficulties in securing payment of the taxes due to fund the business, there was nothing but frustration, tinged with humiliation. This was not at all what he’d envisaged.

Construction of Margaret was followed by the commissioning of Treasurer, built by Martin le Nault of Le Conquet at a further cost of £1,085 Scots. More vessels were purchased including Robert Barton’s Colomb, which was quickly engaged in the west, cruising from Dumbarton under the capable John Merchamestone to recover Brodick Castle, seat of the Earl of Arran, seized by Walter Stewart. When King James wrote to Hans of Denmark in August 1505, he had to concede that he had no capital ships available, such were the demands of home service, making good storm damage, wear and tear, with other vessels detached on convoy duty. In part, this deficiency could and had to be made up by hire or joint venture agreements with merchants/privateers such as the Bartons, but it was clear more capital ships were needed. By 1507, work on the construction of the New Haven was already far advanced and the king was considering the possibilities of Pool of Airth, well to the west of the fort at Invergarvie and thus far more sheltered from attack. By the autumn of 1511, three new docks had been built under the direction of Robert Callendar, Constable of Stirling Castle, who had received £240 Scots to meet the costs involved.

Impressive as the construction of the great ship Margaret had been and as much as she represented the best in contemporary warship design, she was insufficient to satisfy James’s obsession with capital ships. As early as 1506, the king had engaged James Wilson of Dieppe, a Scottish shipwright working in France, to begin sourcing suitable timbers for a yet larger project. This new vessel, Michael, was to define the Scots Navy of James IV. A later chronicler estimates its cost as not less than £30,000 Scots, a truly vast outlay. Finding adequate supplies of timber to build her hull and furnish the planking gobbled up much of Scotland’s natural resource with much else imported besides. She would have weighed at least 1,000 tons with a length of 150–180 feet. Her main armament probably totalled 27 great guns with a host of smaller pieces, swivels and handguns. Henry VIII, not to be outdone in what was developing into a naval arms race, commissioned Great Harry, which went into the water a year later. For James this was imitation as flattery; the fact that Michael was afloat, moved Scotland into the first rank of maritime powers. A Scots Navy had now fully ‘arrived’. The new ship took to the water for the first time on 12 October 1511. She had been nearly five years in the making and carried a full complement of around 300 of whom 120 were required to serve the great guns.

James took an enormous pride in his flagship. At that moment, she was likely the most powerful and advanced warship that had ever sailed. Her very existence heralded Scotland as a European power. His nascent navy now comprised in addition to Michael and Margaret, the capital ships Treasurer and James with smaller but still potent men-of-war in Christopher and Colomb, plus a couple of substantial row-barges and lesser craft. This royal squadron could be further up-gunned by the private vessels of the Bartons and seafarers such as Brownhill, Chalmers, Falconer and, of course, Sir Andrew Wood. Not only had the king created a navy, but the sea was his passion to a far greater extent than appears to have been the case with any of his forebears. It was thus the crowning irony of his reign that this fine instrument of war was never really tested in battle. For James, the great trial came on land, in the rain, at the end of a wet summer in September 1513, not on some great field of European destiny but the habitual graveyard of North Northumberland. The catastrophe of Flodden cast a perpetual dark shadow over the king’s memory, his creation of a Scottish navy a mere footnote by comparison. In the final, dolorous act, the regency council sold Michael to their French allies for something less than half of what she’d cost to construct. It was an ignominious and inglorious ending to so great an enterprise.

What then did James achieve, if anything? For a brief and untried moment he projected the image of Scotland as a power of the first rank, or very close, a status she had not enjoyed before and would not resume. The cost in treasure to the nation had been very considerable, though the yards provided much employment and created a more sophisticated shipbuilding industry. It is true that, during his reign, no successful attacks were launched against the Forth. Lack of a naval presence would bear bitter fruit during the harrying of the Rough Wooing in the 1540s. To that extent, James’s policy of aggressive defence was a success, and his victories over the dissident clans and Islesmen in the west should not be overlooked. In spite of these very real achievements, it is impossible to escape the fact that this fledgling navy did not survive his violent death. The construction of the fleet had been due in no small part to the French alliance and the king’s ability to source skilled men and sound materials from French ports and forests. Had the disaster at Flodden not occurred, the naval history of Scotland might have followed a different course. In those few hours of frenzied, doomed carnage James and his realm lost all he had created.