Successive Royal Navy post-Dreadnought classes were basically improved versions of that pioneering warship. The next significant advance came with the Orions (Orion, Conqueror, Monarch, and Thunderer, constructed between 1909 and 1912). They were improvements over previous designs and were promptly called super dreadnoughts. Their new 13.5-inch guns gave considerably increased firepower for a small addition in weight and size; range was increased to a spectacular 24,000 yards. The Orions’ main batteries were arranged on a pattern pioneered by the U. S. Navy that would prevail until the last battleship was designed: All turrets were mounted on the centerline, and fore-and-aft turrets were superimposed one on the other, a vast improvement on the German and previous RN wing turrets. The Orions’ armor was extended up to the main deck, eliminating a major weakness of the early dreadnought classes. Still, they suffered from the same lack of beam, which gave inferior underwater protection compared to the German ships. The unsound British argument was that greater beam made the ship more unsteady and reduced speed. The Orions, as noted, were also the last RN dreadnoughts to position their firing platforms directly abaft the forward funnel.

The next major advances in battleship design were seen in the five impressive Queen Elizabeths (Queen Elizabeth, Valiant, Barham, Malaya, and Warspite, completed in 1915-1916). Well ahead of anything the German Navy would produce, they were confidently designed to outrace a retreating enemy fleet. The Queen Elizabeths were the world’s first large oil-burning warships. The Admiralty knew full well that the Germans would be unlikely to go over to oil-burning entirely, as the Germans, unlike the British, were presumed to lack an assured oil supply in wartime. (Of course, with their penchant for invading other countries, the Germans might have been expected to take over Romania’s oil fields, which is what they later did in World War I.) Also, oil gave considerably greater thermal efficiency, discharged much less smoke, and released all personnel from the filthy, time-consuming bondage of coaling. Oiling was simply a matter of running out hoses and opening valves. Thus Great Britain, with no domestic oil resources of its own, had given hostages to the world’s petroleum producers.

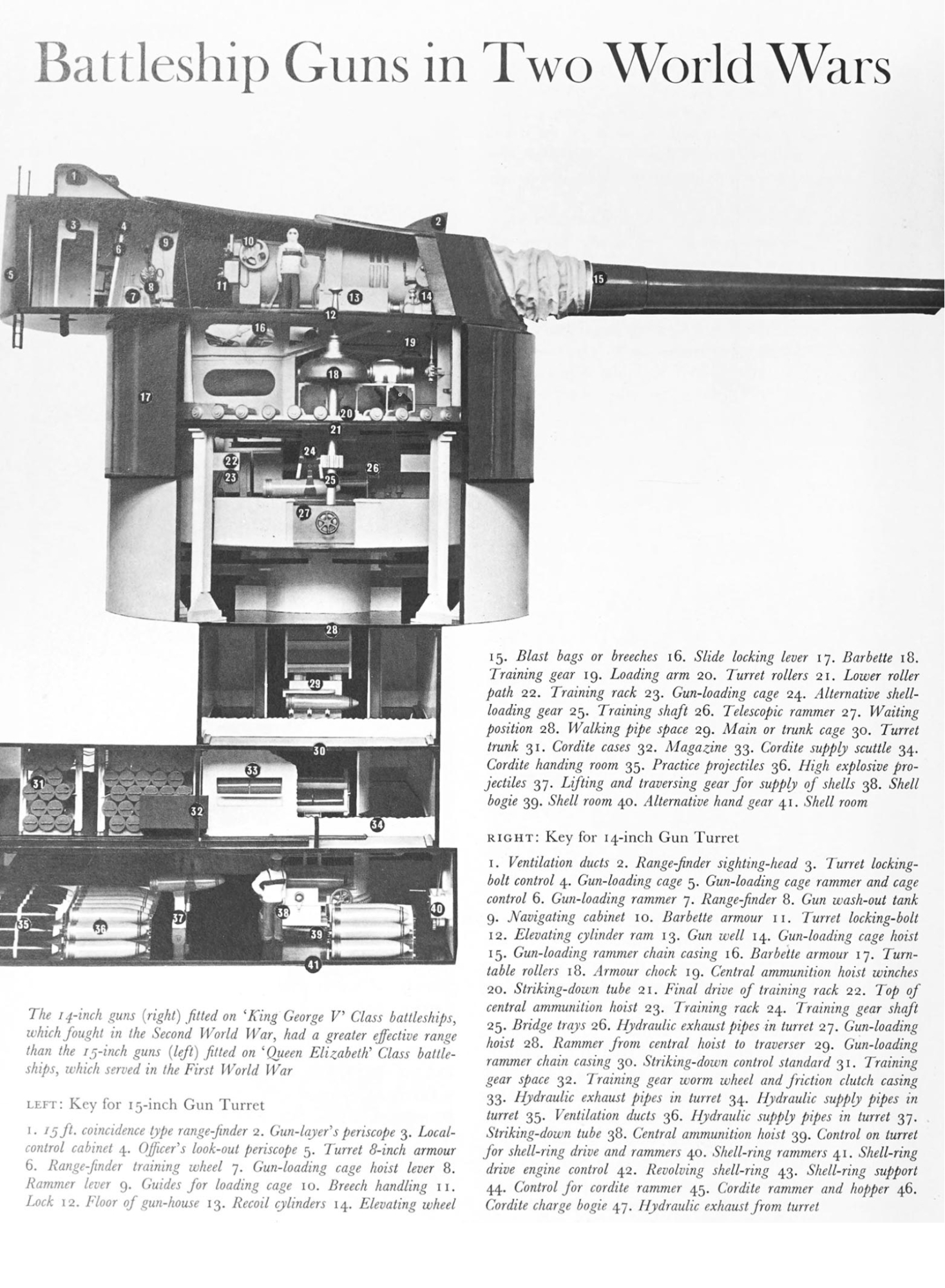

The Queen Elizabeths were also the first to mount 15-inch main battery guns, and all five units fired those guns at Jutland. They and two units of the following Revenge class (Revenge, Royal Oak, Ramillies, Resolution, and Royal Sovereign, completed 1916-1917) were the last RN battleship class to fight in World War I and, with the Elizabeths, were the only capital ships of any naval power to use their main guns against enemy battleships in both world wars. (Three more units, Renown, Repulse, and Resistance, were suspended, then canceled in 1914 at the outbreak of war.)

The dreadnought was easily the most expensive weapon of World War I. By contrast, the most costly war tool of World War II (1939-1945) was the U. S. Army Air Force’s B-29 Superfortress heavy bomber. Obviously, the battleship’s status had considerably depreciated since 1918; not one battleship was laid down and completed during World War II.

Yet paradoxically, there were considerably more battleship-to-battleship clashes in World War II than in World War I, although, as in World War I, there would be only one large fleet battleship action. Yet despite their diminished role in World War II, roughly the same number of battleships would be lost as in World War I (23 versus 25, including self-scuttlings).

Like the other naval powers, all battleship-oriented, the Royal Navy entered World War II with a collection of World War I-era battleships, modernized and unmodernized, and with new battleships on the way. It also had the only battleships in any navy designed and completed during the 1920s, Nelson and Rodney. Except for the Nelson class, the Royal Navy during World War II would lose one each from its other battleship classes, in all losing three battleships: Royal Oak, Prince of Wales, and Barham. The oldest of the Royal Navy’s battleships serving in World War II were the five Queen Elizabeths. Of them, Valiant, Warspite, and Queen Elizabeth had been given the most complete reconstructions of any RN battleship. The unmodernized Barham would be lost to submarine torpedo, taking 862 crewmembers, in 1941. Later came the five Royal Sovereigns, of which Royal Oak was lost in Scapa Flow, with 786 dead, in 1939, again to a German submarine torpedo. These later but cheaper warships were not as highly valued as the Queen Elizabeths, perhaps because they were slower and they did not undergo nearly as extensive a modernization. In fact, the Admiralty seriously considered expending two of this class as blockade ships off the German coast. One, Royal Sovereign, was loaned to the Red Fleet for the war’s duration.

The newest RN battleships of World War II were the King George V class (King George V, Prince of Wales, Duke of York, Anson, and Howe, not to be confused with the King George V class of 1911-1912). Again, one unit of this class, Prince of Wales, was lost during the war, this time to aerial attack by the Japanese in December 1941. The class was severely criticized for its 14-inch main guns. This retrograde decision (after all, the considerably older Nelson and Rodney boasted 16- inch guns) was made in order to get at least the first two units of the class completed in 1940, by which date conflict with Germany was expected. As it was, only King George V was ready for service in 1940. Like the Nelson class, the King George V class had significant maingun mounting problems. Nonetheless, the Royal Navy generally felt that the class gave good value for the money.

A follow-on class, the Lions, was designed to mount 16-inch guns, but the realities of World War II saw to it that these battleships did not get past the laying-down stage, if that. Even so, as late as 1943-1944, there was actually a brief flurry of interest in completing the Lions, which went nowhere. Two years into World War II, Great Britain laid down HMS Vanguard as a mount for the never-installed 15-inch guns of the freak giant battle cruisers Glorious and Courageous, long since converted to aircraft carriers. Vanguard was basically Winston Churchill’s idea (the prime minister always had a soft spot for battleships) and was supposed to reinforce the RN fleet at Singapore. But long before Vanguard was launched in 1944, the Singapore bastion had fallen ignominiously, and Prince of Wales (along with the battle cruiser Repulse) had been lost to Japanese airpower off Malaya. Work proceeded very slowly during the war on Vanguard, the largest and last British battleship ever built; it was not completed until 1946, never fired a shot in anger, and was scrapped in 1960.

The cancellation of the Lions and the slow pace of construction on Vanguard should not be taken as an indication that the Royal Navy had given up entirely on battleships. Incredibly, the First Sea Lord (i. e., the highest-ranking RN officer), Admiral Andrew Cunningham, in May 1944, well after Taranto, Pearl Harbor, and the loss of Prince of Wales and Repulse, argued that, for the postwar Royal Navy, “the basis of the strength of the fleet is in battleships and no scientific development is in sight which might render them obsolete” (quoted in Eliot A. Cohen, Supreme Command: Soldiers, Statesmen, and Leadership in Wartime, New York: The Free Press, 2002, pp. 121-122). Admiral Cunningham was no armchair theoretical navalist, but probably the best admiral the Royal Navy produced during World War II. Yet by the time Cunningham made his lamentable projection, the Royal Navy had ceased all battleship construction except for its leisurely work on Vanguard; after World War II it would lose no time in scrapping all its surviving battleships (except for Vanguard).

ADM 234/509

– Page 198 –

[Enclosure(III)]

REPORT ON EVENTS WHICH OCCURRED IN 14in TURRETS

23rd TO 25th MAY

Friday, 23rd May

A – Events prior to First Action

The order to load the cages was given late in the afternoon. In the course of loading the following defects developed:-

“A” Turret

No. 2 gun loading cage: Front flashdoors could not be opened fully from the transverser compartment and the cage could not be loaded. Examination showed that the front casing had been badly burred by being struck by the lugs carrying the guide rollers on the gun loading rammer head when the latter was making a “withdrawing” stroke.

This was cleared by filing and the other gun loading cages were examined for the same defect. Slight burring was found in some cases and was dressed away.

No. 1 gun: On ramming shell the second time after the order “Load”, the shell arrestor at the shell ring level jammed out and could not be freed before the first action.

While steaming at high speed, large quantities of sea water entered “A” turret round the gun ports and through the joints of the gunhouse roof. It became necessary to rig canvas screens in the transverser space and bale the compartment.

“B” Turret

No. 2 central ammunition hoist: Arrestor at shell ring level would not withdraw after ramming shell. It is impossible to strip this in place in the Mark II mounting, and the arrestor was removed complete. The axis pin of the pinion driving the inner tube of the arrestor had seized. There does not appear to be any effective means of lubricating this pin. The pin was drilled out and removed and the arrestor re-assembled. It was not, however, possible to replace the arrestor before action stations was ordered, because at this stage a defect developed in the hinge trays of the forward shell room as described below. This latter defect was taken in hand immediately in order to free the revolving shell ring and was completed a few minutes after action stations. It was not then considered advisable to proceed with replacing the arrestor.

Hinge trays at forward shell room fouled the locking bolt on the revolving shell ring: both trays being bent.

Saturday, 24th May

During the early hours hydraulic pressure failed on the revolving shell ring ship control in “B” turret. This was due to the pressure supply to the turret from the starboard side of the ring main being isolated. The revolving shell ring ship control is fed from the starboard side only, and the non-return valves on the pressure main adjacent to the centre pivot prevent pressure being fed to the starboard side and the revolving shell ring ship control from the port side in the event of the former being isolated from the ring main. Similar conditions exist on the port side of “A” and the starboard side of “Y”. It is considered essential that a cross connection be fitted in the shell handling room with two non-return valves so that the revolving shell ring ship control can be supplied from either side of the ring main.

B – Events during the First Action

The following defects developed in “A” turret:-

“A” Turret

On several occasions the shell ring rammers fouled the brackets on the hinge trays for No. 11 interlock. Shell could not be rammed until the bearing of the turret was changed. This also occurred in “Y” but did not prevent ramming.

No. 1 gun only fired one salvo, due to the events described in A (i).

After the second salvo, No. 24A interlock failed on No. 2 shell ring rammer. It was tripped after a short delay and thereafter assisted by hand.

About halfway through the firing, the tappets operating the shell ring arrestor release gear on No. 4 rammer failed to release the arrestor. Subsequent examination has shown that the shaft carrying the levers operating these tappets had twisted. The rammer was kept in action by giving the tappets a heavy blow at each stroke.

Shortly after this, a further defect occurred on No. 4 shell room rammer. When fully withdrawn the rammer failed to clear No. 7 interlock and the ring could not be locked. This was overcome by operating the gear with a pinch-bar at every stroke.

Throughout the engagement the conditions in “A” shell handling room were very bad; water was pouring down from the upper part of the mounting. Only one drain is fitted and became choked; with the result that water accumulated and washed from side to side as the ship rolled. The streams above and floods below drenched the machinery and caused discomfort to the personnel. More drains should be fitted in the shell handling room and consideration given to a system of water catchment combined with improved drainage in the upper parts of the revolving structure. Every effort is being made to improve the pressure systems and further attempts will be made as soon as opportunity occurs to improve the mantlet weathering, but a certain amount of leaking is inevitable.

“B” Turret

No mechanical defects.

“Y” Turret

The following defects occurred in “Y” turret:-

Salvo 11 – No. 3 central ammunition hoist was raised with shell but no cordite; No. 25 interlock having failed to prevent this. The interlock was functioning correctly before the engagement. There has been no opportunity to investigate this. It is also reported that the reason no cordite had been rammed was that the indicator in the cordite handling room did not show that the cage had been raised after the previous ramming stroke. This caused the gun to miss salvoes 15 to 20.

Salvo 12 – Front flashdoors of No. 2 gun loading cage failed to open and cage could not be loaded. Flashdoors on transfer tubes were working correctly and investigation showed that adjustment was required on the vertical rod operating the palm levers which open the gun loading cage doors. To make this adjustment, three-quarter inch thread had to be cut on the rod. This defect was put in hand after the engagement had been broken off and was completed by 1300. It would appear that the operating gear had been strained, possibly by the foreign matter in the flashdoor casing making the doors tight. The doors were free when tried in the course of making the repair. This caused the gun to miss salvo 14 onwards.

Salvo 20 – Owing to the motion of the ship, a shell slid out of the port shell room and fouled the revolving shell ring while the latter was locked to the trunk and the turret was training. The hinge tray was severely buckled, putting the revolving shell ring out of action. The tray was removed, but on testing the ring it was found that No. 3 and 4 hinge trays of the starboard shell room had also been buckled and were fouling the ring. The cause of this is not yet known. The trays were removed and as the action had stopped by this time, No. 4 tray was dressed up and replaced. The ring was out of action until 0825.

C – Events subsequent to First Action

During the day in “A” turret, No. 1 central ammunition hoist shell arrestor was driven back with the intention of carrying on without it by ramming cautiously. The gun and cages were then loaded, but owing to the motion of the ship the round in the central ammunition hoist cage slid forward until its nose entered the arrestor, putting the hoist out of action again. Subsequent examination has shown that the anti-surging gear in this cage was stiff and consequently did not re-assert itself after ramming to traverser.

D – Events during the Second Action

“A” Turret

No. 1 gun fired only two salvoes owing to central ammunition hoist being out of action as described above in C, para 1. At salvo 9, No. 3 central ammunition hoist shell arrestor jammed out.

“B” and “Y” Turret

Clean shoot.

E – Events subsequent to Second Action

“A” Turret

No. 3 central ammunition hoist shell arrestor was removed complete from the hoist. Time did not allow of it being stripped and made good, but it was intended to use the hoist without it. The gun and cages were loaded in this manner.

F – Third Action

“A” Turret

First Salvo – Shell rammed short into No. 3 central ammunition hoist cage. In trying to remedy this a double ram was made, putting the shell ring out of action. The second shell was hauled back by tackle, clearing the ring. The base of the shell in the central ammunition hoist cage was jamming against the upper edge of the opening in the hoist. This could not be cleared as the central ammunition hoist control lever cold not be put to lower. After much stripping the trouble was located in a link in the control gear which was found to be out of line.

“B” Turret

Clean shoot.

G – General

With pressure being kept on shell room machinery for a long period, much water has accumulated in the shell rooms and bins. Suctions are fitted from 350-tomnm pumps only and these are not satisfactory for dealing with relatively small quantities of water. Drains are urgently required. It is suggested that a drain be fitted at each end of each shell room and larger drain holes be made in the bins; present drain holes being quite inadequate and easily choked.

The drains should be led to the inner bottom under the cordite handling room. Non-return valves and flash-seals could be fitted if considered necessary.

On passage to Rosyth after the action, two further hinge trays in “Y” shell handling room were buckled by fouling the revolving shell ring.