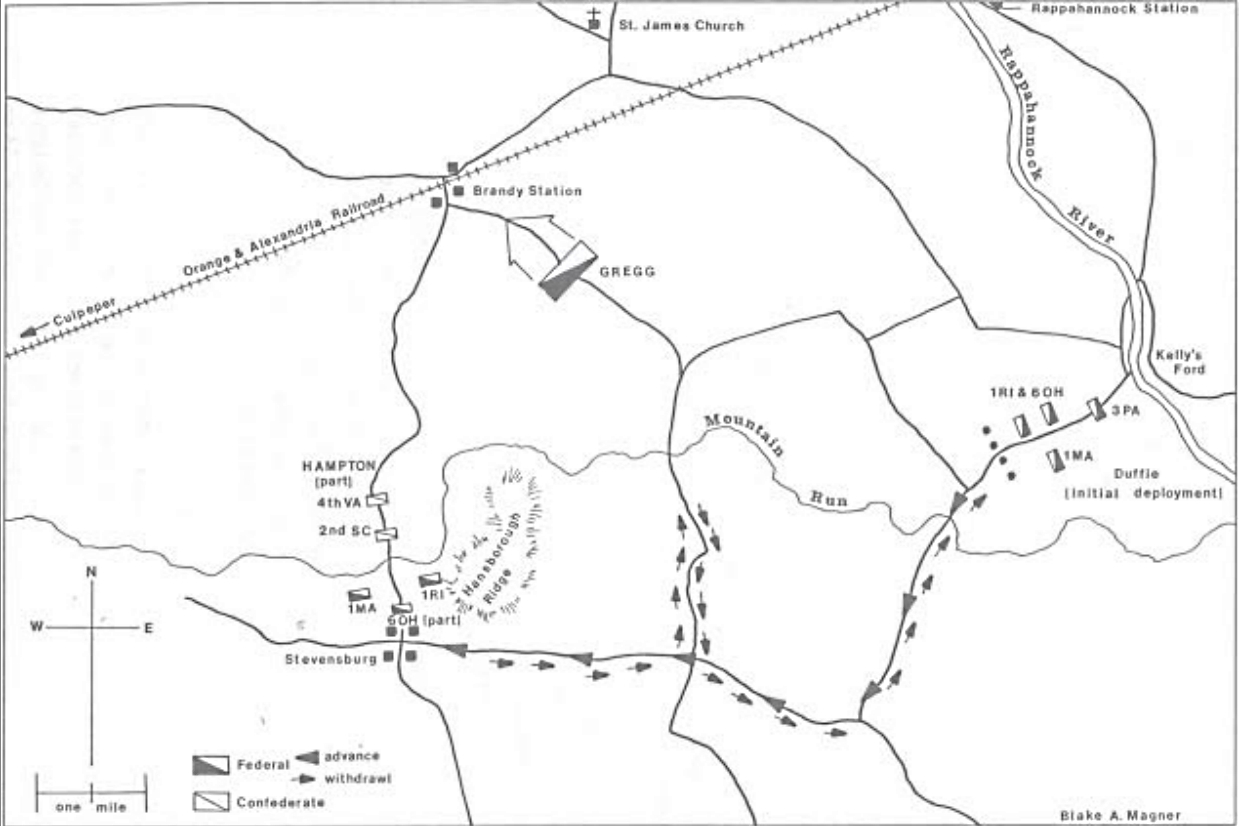

The Action at Stevensburg, June 9, 1863.

DUFFIÉ AT STEVENSBURG

Duffié received the order to move his command to Kelly’s Ford at 12:15 a.m. on June 9. Gregg instructed the Frenchman to march his division “directly upon Stevensburg, following the road leading to Raccoon Ford. Arrived at Stevensburg, you will halt and communicate with our forces at Brandy Station, and from this point communication will be had with you.” Gregg’s division would follow along behind on the same road. While the Pennsylvanian moved on Culpeper from Brandy Station, Duffié would advance on Culpeper from the south after leaving a regiment and a section of artillery at Stevensburg to guard the river crossings. “It is intended that when the right of our line at Brandy Station advances toward Culpeper, your division at Stevensburg will also move upon Culpeper,” instructed Gregg.

Reveille sounded in Duffié’s camps at 1:00 a.m. “It was well past twelve before we got down to sleep and I for one was just dozing off—had not lost consciousness—when reveille was somewhere sounded,” recalled Captain Charles Francis Adams of the 1st Massachusetts. “‘That’s too horrid,’ I thought, ‘it must be some other division.’ But at once other bugles caught it up in the woods around.” Soon the blueclad horsemen were stirring and getting ready to march. They had only five miles to cover to reach the rendezvous point with Gregg’s division. They had no idea what lay ahead of them as they set off on the five-hour march to Kelly’s Ford.

Upon arriving, the Frenchman was to report to Gregg for further orders, cross the river, and advance to Stevensburg, where he was to protect Gregg’s flank on the march toward Culpeper. If Duffié controlled the road from Stevensburg to Culpeper, the Frenchman and his troopers would be in a perfect position to cut off Stuart and either force the Virginian to fight his way out of the trap or be captured. Gregg ordered the French sergeant not to use guide fires, which might give away his position. Because his division had to traverse an unfamiliar road network through a dark night, the march took longer than expected. A local guide insisted that a fork in the road led toward Kelly’s Ford, so the column proceeded. After continuing on, Duffié realized that the guide was wrong and ordered his men to turn around and backtrack. This misstep delayed their arrival even longer as they pressed on through the dense fog. After meeting Gregg, Duffié crossed the river and deployed in line of battle on the Stevensburg Road. “We crossed the Rappahannock without molestation, the Rebs having been driven back early in the morning, about 4 AM,” noted an officer of the 3rd Pennsylvania Cavalry.

Luigi Palma di Cesnola’s brigade led Duffié’s advance. The Italian count deployed the 1st Rhode Island and the 6th Ohio on the right and the 1st Massachusetts on the left and kept the 3rd Pennsylvania in reserve. The sound of the guns booming at St. James Church “buoyed us up—tho some got pale—yet every man looked ready for the fray,” as a member of the 16th Pennsylvania Cavalry described it. They waded across fast-moving Mountain Run, a tributary of the Rappahannock that was prone to flooding, near Paoli’s Mill and pressed on.

In this array, Duffié advanced slowly toward Stevensburg, sending a battalion of the 6th Ohio forward to scout. At about 8:30 a.m., Major Benjamin C. Stanhope of the 6th Ohio sent back word that he had reached Stevensburg, that the enemy was in sight, and that he had sent skirmishers forward to meet them. Lieutenant William Brooke-Rawle of the 3rd Pennsylvania Cavalry reported, “From a hill I caught a beautiful glimpse of the advance. The skirmishers deployed in front, supported by their reserves, one column, with the artillery, advancing on our left along the road, & our regiment advancing in echelons of squadrons supporting both the battery & skirmishers. All the guidons flying, & the effect was beautiful.” Stanhope’s men captured seven pickets, including the lieutenant commanding the vedettes.

Wade Hampton’s foresight ensured that Confederate forces guarded Stuart’s flank. When he learned that Gregg’s command had crossed at Kelly’s Ford, Hampton rode to the camp of Colonel Matthew C. Butler’s 2nd South Carolina Cavalry and ordered Butler to mount his regiment and move it to Brandy Station to await further orders. Butler sent a squadron under command of Captain Leonard Williams to picket Stevensburg and moved the rest of his regiment to Brandy Station as ordered. No sooner had these pickets arrived than they spotted Duffié’s advance guard approaching. “When a regiment and then a brigade of Yankees came in sight and drew up in battle line, I attracted their attention,” recounted Williams. “They threw out their skirmishers the length of a mile in front of me. They advanced briskly. I kept out my videttes and placed my squadron back across the stream, dismounted the men to hold them in check as long as possible.” Williams sent a galloper to Butler bearing this unwelcome news.106 Knowing there were no other Confederate forces in the area, and without waiting for orders, Butler ordered his entire regiment to move to Stevensburg.

Matthew Butler was a fine soldier. Born on March 8, 1836, in Greenville, South Carolina, Butler practiced law before the Civil War. When the war broke out, he received a commission as a captain in the Hampton Legion and was promoted to major after First Bull Run. In August 1862, he became colonel of the 2nd South Carolina Cavalry. Young and aggressive, Butler was one of the better regimental commanders. By the end of the war, he wore a major general’s stars and commanded a division under Hampton. This day, he proved to be the right man in the right place.

Protecting the road between Stevensburg and Culpeper was critical—Longstreet’s infantry corps was camped around Pony Mountain about midway between Stevensburg and Culpeper, and Ewell’s corps was farther north of Culpeper; Brigadier General Junius Daniel’s infantry brigade could see some of the action on Fleetwood Hill from its camps. The cavalry sought to screen the presence of the Confederate infantry at all costs. Knowing the urgency of the situation, Butler ordered his second-in-command, Lieutenant Colonel Frank Hampton, younger brother of Wade Hampton, to gallop on to Stevensburg with twenty men to do what they could to delay the Yankee advance. Butler wanted Hampton to buy sufficient time for him to deploy his little force on the commanding high ground known as Hansbrough’s Ridge, just outside Stevensburg. “The position in which Butler awaited attack was well chosen. The woods concealed the smallness of his numbers, and even on the road the sloping ground prevented the enemy from discovering any but the leading files of Hampton’s detachment.” Butler’s lone regiment of two hundred men had to defend a line along Hansbrough’s Ridge that was nearly a mile long, a difficult task at best.

When Hampton and his small contingent arrived at Stevensburg, they learned that although the Yankees had already passed through the town, they had withdrawn after Confederate vedettes fired on them. Hampton dismounted part of his little force in front of a stately plantation house called Salubria, keeping part of his command mounted and at the ready. With a scratch force of thirty-six men, Lieutenant Colonel Hampton ordered his men to charge the Yankee column, which withdrew instead of engaging. “The fight opened by the rebels, who charged the First Massachusetts Cavalry down a hollow road,” recounted Captain Walter S. Newhall of the 3rd Pennsylvania Cavalry. “They came to the conclusion that they ‘had the wrong chicken by the tail feathers,’ and very shortly changed base, with a loss of twenty-five killed and wounded and a loss of sixty-four prisoners.” Thus, Hampton’s delaying action bought time for the rest of Butler’s regiment to march to Stevensburg and deploy into line of battle.

Captain Williams of the 2nd South Carolina found his little command completely surrounded by bluecoats when the sheer weight of Yankee numbers finally forced his squadron back: “I discovered that a Yankee regiment was in front of me, the rear vidette, I suppose, captured. I was thus completely cut off, a brigade in my rear, a regiment on the road in my front and neither more than 500 yards from me.” Williams and his thirty men turned into the woods and tried to make their way across country to rejoin Stuart’s main body at Brandy Station. “On nearing the place, I halted the column and went towards the road to reconnoiter and found they had passed upon and heard 2 or 3 consecutive charges. On hearing it again, halted to examine.”

Williams found no Northerners on the road between Stevensburg and Brandy Station, so he ordered the column forward again. “I discovered that I was encompassed on all sides and then carried my squadron back into the densest wood I could find with the intention of remaining til night and then running the gauntlet through their lines.” However, at about three o’clock, Williams’s vedettes reported that the Yankees had been repulsed and the road between Brandy Station and Stevensburg was clear. “It was universally supposed that we had been captured. I attribute our safety to a divine providence,” reported the relieved South Carolinian.

While Butler deployed his troops, the famous Confederate scout Captain Will Farley galloped up with a message from Stuart, informing Butler that a single piece of artillery, along with the 4th Virginia Cavalry under command of Colonel Williams C. Wickham, was on its way to reinforce Butler. As the Virginians arrived, Wickham sent Lieutenant Colonel William H. Payne forward to alert Butler that the reinforcements had arrived. Butler responded, “[I] requested Colonel Payne to inform Colonel Wickham of the disposition I had made of the few men at my disposal and to say to him, as he reached me, I would cheerfully take orders from him.” Wickham, who was senior to Butler, declined to assume command, so Butler requested that Wickham bring two mounted squadrons of his command forward to support Hampton’s squadron. The rest of the 4th Virginia would come into line dismounted alongside the balance of Butler’s regiment. By this time, it was approximately 11:00 a.m., and the desperate battle raged at Brandy Station as the first elements of Gregg’s command reached Fleetwood Hill.

Duffié approached tentatively. He sent mounted skirmishers forward, but they withdrew after a few volleys from Butler’s dismounted troopers. “As the first brigade of Duffié advanced, the dismounted men, well protected, fired upon our men, who were mounted, and made the advance uncomfortable,” recounted an officer of the 1st Massachusetts. “One carbine in the hands of a dismounted man under cover is certainly worth half a dozen in the hands of men on horseback; and these men of Hampton, on our left of the road, were in the ruins of a large, burned building, a seminary, and delivered a hot fire upon the advance of the 1st Massachusetts, which was opposed to them.”

“I sat on my horse skirmishing within 2 rods of the same place for 15 minutes[,] firing as fast as I could get a sight at one[,] they being concealed behind some farm houses and stone walls[.] [W]hen they would step out to fire we would pull,” recounted a horse soldier from Massachusetts. “We were in an open field. They had got a good range of us and our men and horses began to fall when our supporters came up in line of battle out of some woods.” Taking heavy enemy fire that rattled the rails, the Bay Staters pulled down a split rail fence so that their horses could pass through. Even though Duffié had not ordered an attack, the Massachusetts horsemen drew sabers and advanced. “We charged. They mounted their horses in a hurry and skedaddled toward Culpeper. We followed them about 5 miles and met their batteries coming up and had to retreat.”

The grayclad horsemen repulsed a second probing attack, and the Federals shifted the focus of their attack to Hampton’s small mounted contingent waiting in the road. “I immediately threw forward the skirmishers of the First Massachusetts, First Rhode Island and Sixth Ohio Cavalry, who immediately became engaged with the enemy, who were strongly posted and partly concealed in the woods,” Duffié reported. “Pushing steadily forward, the enemy were quickly dislodged from those dense woods into open fields, where the First Rhode Island Cavalry was ordered to charge on the right, the First Massachusetts on the left, and one squadron of the Sixth Ohio Cavalry on the road, in order to cut off the retreat of the enemy on his flank and check him in his front.”

“We drew sabers and started on the charge,” recalled Sergeant Albert A. Sherman of the 1st Massachusetts. “The rebels stood until we got within a few yards of them. I thought we had got into a bad fix; but before we got to them, they broke and ran like a flock of sheep toward the village, and we in among them using the sabre. I followed one man and called to him to surrender, but he took no notice of it. I soon reached him and struck him between the shoulders with the staff of the guidon. It knocked the breath out of him and he surrendered.” The South Carolinians attempted to make a stand, but the overwhelming force of Union horse soldiers scattered them.

“Imagine my surprise when I learned from the right that a regiment of the enemy’s cavalry had charged Colonel Hampton’s handful of men and swept him out of the road,” recounted Butler. “In the melee, Colonel Hampton received a pistol ball in the pit of his stomach and died that afternoon from the effects of it.” Duffié’s attack crashed into Butler’s line. In the process, the force of the Federal charge cut the 4th Virginia in two and sent it flying from the field in disorder. The Virginians “broke in utter confusion without firing a gun, in spite of every effort of the colonel to rally the men to the charge.” “It was a regular steeple chase,” recalled a Federal, “through ditches, over fences, through underbrush.” A.D. Payne, a member of the 4th Virginia, lamented, “Oh memorable day.…A disgraceful rout of the Regiment.” Duffié captured more than forty of the Virginians in this charge.

Many years after the battle, Butler wrote, “Colonel Wickham not only did not move up his mounted and dismounted squadrons to Colonel Hampton’s support, but when the enemy charged they took to their heels toward Culpeper Court House.” To his credit, Wickham made no excuses for the conduct of his regiment. “I regard the conduct of my regiment, in which I have heretofore had perfect confidence, as so disgraceful in this instance that…the major general commanding, to whom I request that this be forwarded, may have the facts before him on which to base any inquiry that he may see fit to institute.”

Duffié re-formed his command on a hill just to the west of Hansbrough’s Ridge and pressed forward once again as Butler struggled to rally his small force. Seeing this, Duffié brought up Lieutenant Alexander C.M. Pennington’s Battery M, 2nd U.S. Artillery, and unlimbered two guns on a small rise. There, the guns opened on Butler’s line, wreaking havoc. Butler and Will Farley were the only Confederates still mounted at that time, and they provided a convenient target for the Federal guns. Supported by the artillery, Duffié ordered another charge.

Seeing the approaching Federals, Farley drew his revolver, spurred his horse forward, and opened fire. Butler ordered the officer in command of Company G, positioned next to Farley, not to fire too soon in order to protect men of Butler’s regiment who might have gone forward to escape the artillery. “When, however, we discovered the enemy making their way through the bushes and opened fire, I gave the command, ‘Commence firing’ all along the line. I noticed a mounted cavalryman in blue slide off his horse…very easily, and the horse trot back to his rear, and assumed he had dismounted not more than fifty yards down the hill for the purpose of getting the protection of a tree in his future efforts,” recalled Butler. “About that time a man wearing a striped hat turned to me and said, ‘Colonel, I got that fellow.’ I replied by saying, ‘Got him, the devil; he has dismounted to get you; load your gun.’ It turned out…he was right. He had killed this man, who proved to be an officer.”

Butler realized that the rout of the 4th Virginia had turned his flank, so he redeployed his command in a valley near Norman’s Mill on Mountain Run, just north of Stevensburg. His men cobbled together a second line of battle on the other side of the creek. Butler also deployed his single gun there. It opened counterbattery fire with Pennington’s guns atop the hill.

As the artillery duel continued, and as Duffié redeployed his forces, a short lull occurred in the fighting. Farley and Butler sat on their horses, facing opposite directions, laughing as Butler recounted to Farley the anecdote about the Federal officer killed by his men. Butler had his back to the Federal position, not paying much attention to the artillery fire. “Suddenly, [a] twelve pound shell from the enemy’s gun on the hill (we had evidently been located by a field glass), struck the ground about thirty steps from our position in an open field ricocheted and passed through my right leg above the ankle, through Farley’s horse, and took off [Farley’s] right leg at the knee,” wrote Butler. “My horse bounded in the air, threw me, saddle and all, flat on my back in the road, when the poor fellow moved off with his entrails hanging out towards the clover field where he had been grazing in the early morning and died there, as I was afterwards informed.”

Farley’s wounded horse dropped in the road, and Farley fell with his head on the horse’s side. “As soon as we discovered what the trouble was my first apprehension was we would bleed to death before assistance could reach us. I therefore directed Farley to get out his handkerchief and make a tourniquet by binding around his leg above the wound. I got out my handkerchief, and we were doing our best in the tourniquet business when Capt. John Chestnut and Lieutenant John Rhett of my regiment came to our relief, soon followed by…[the] surgeon and assistant surgeon of the regiment.” The surgeon amputated Butler’s shattered leg. Farley was carried from the field on a trough. He asked that his leg be brought to him, and he clutched it close as the South Carolinians carried him to safety. He died later that day. That single artillery shot took quite a toll.

With Frank Hampton dead and Butler badly wounded, Major Thomas J. Lipscomb assumed command of the 2nd South Carolina. In spite of his serious condition, Butler remained calm and collected. “Major Lipscomb, you will continue to fight and fall back slowly toward Culpeper,” he instructed, “and if you can save us from capture do it.” As Lipscomb attempted to rally his forces, deployed in a thin line in the valley below, Duffié saw that he could carry the position and ordered the 1st Massachusetts to charge. As the Bay Staters formed, orders reached Duffié from Gregg that he should “return and join the Third Division, on the road to Brandy Station.” The Frenchman, standing on the hilltop overlooking the thin line of the South Carolinians along Jonas Run in the valley below, could look straight ahead and see the fight raging on Fleetwood Hill, six miles away.

Instead of ordering his men to overrun Lipscomb’s little force and take the direct route to Fleetwood Hill, Duffié obeyed the order explicitly, breaking off and taking a longer, more roundabout route to reach Fleetwood Hill that almost guaranteed that he would arrive too late to be of any assistance to Gregg. Duffié drew off most of his division, leaving the 3rd Pennsylvania Cavalry and one section of artillery to watch Lipscomb’s men and keep them from returning to the main Confederate line of battle at Fleetwood Hill.

This small force remained at Stevensburg for about an hour, but seeing no enemy and hearing the heavy firing booming at Fleetwood Hill, the 3rd Pennsylvania Cavalry marched to the sound of the guns. “We were ordered to fall back to the support of General Gregg, who was being badly beaten,” claimed an officer of the 3rd Pennsylvania. “We came up just in time to save the Third Division.” The Pennsylvanians arrived at about 4:00 p.m., just as the fighting ended on Fleetwood Hill, and the Federals began withdrawing. “After remaining for about an hour…we withdrew to Rappahannock Station,” noted a Pennsylvanian, “and crossed the Ford, having moved along the road which our troops had gained.” The 3rd Pennsylvania then covered the retreat of Duffié’s division, squeezing off a few long-range carbine shots at the pursuing Confederate horse soldiers; the Southerners slowly followed the long Northern column toward Rappahannock Station as it withdrew.

As he advanced toward the sound of the guns, Duffié encountered a squadron of the 10th New York Cavalry, fleeing back toward Stevensburg. Learning that a Rebel charge had routed these men, Duffié spent half an hour deploying into line of battle to protect against any Confederate threats. Finally persuaded that the grayclad horsemen were not about to attack, Duffié resumed his march, connected with Gregg, and deployed his guns to cover the retreat of the Cavalry Corps. A member of the 1st Massachusetts offered an alibi for the Frenchman’s lack of aggression. “Their horses were fresh and ours had been marching hard so we did not catch many of them,” he claimed. These claims rang hollow.

Thus, the Frenchman and his veteran division played no role at all in the great cavalry fight at Fleetwood Hill. “Duffié went home satisfied to be left alone,” claimed Mosby years after the war. The Frenchman had obeyed Pleasonton’s orders about guarding the Federal flank, but the flawed premise of the plan meant that an entire division was held out of the great struggle for Fleetwood Hill. “This country is under obligation to Hampton and his brigade,” proudly announced one of Butler’s officers. Had he not lost an entire day to the stubborn resistance put up by Butler’s small but intrepid band, Duffié’s 1,900 troopers may very well have tipped the scales in favor of Gregg’s men in the fight for Fleetwood Hill. “It so happened that Colonel Duffié’s second division went to the left after crossing Kelly’s Ford, and only a very insignificant part of one of the brigades was engaged,” observed a member of the 1st Massachusetts Cavalry. “The rest of the division, two brigades, was not engaged at all; and the loss was comparatively insignificant.”

“We were not very actively engaged or under heavy fire and our loss did not exceed ten or a dozen,” reported Captain Adams of the 1st Massachusetts. “The day was clear, hot and intensely dusty; the cannonading lively and the movements, I thought, slow.” One thing struck Adams. “I saw but one striking object—the body of a dead rebel by the road-side the attitude of which was wonderful. Tall, slim and athletic, with regular sharply chiseled features, he had fallen flat on his back, with one hand upraised as if striking, and with his long light hair flung back in heavy waves from his forehead.” The vision of that dead Southern horse soldier remained with Adams for years.

That they did not play more of a role at Brandy Station bothered Duffié’s men. Sergeant Samuel Cormany of the 16th Pennsylvania, who spent the day watching the battle from a nearby hillside, complained, “Am just too sorry that I and our squad could not perform our part in this day’s fighting.” Thus, the combination of hard fighting by Butler’s single regiment and Duffié’s undue caution stopped an entire division of Union cavalry. The division’s absence made the difference in the ferocious fighting raging around Fleetwood Hill.

THE GREAT BATTLE ENDS

As the fight for Yew Ridge raged, a trooper of the 6th Virginia Cavalry spotted Robert E. Lee “riding across the fields on his gray horse ‘Traveller,’ accompanied by his staff. He seemed as calm and unconcerned as if he were inspecting the land with the view of a purchase.” After receiving a dispatch from Stuart describing Pleasonton’s furious assault, Lee had decided to ride to the battlefield to see what all of the noise was. Lee informed Stuart that two divisions of Confederate infantry were nearby and that Stuart was “not to expose his men too much, but to do the enemy damage when possible. As the whole thing seems to be a reconnaissance to determine our force and position, he wishes these concealed as much as possible, and the infantry not to be seen, if it is possible to avoid it.” Lee wanted to avoid tipping his hand regarding the proximity of his infantry. However, as the day dragged on and the fighting grew more desperate, the Confederate commander finally dispatched Confederate infantry to come to Stuart’s support.

Earlier in the afternoon, Hooker gave Pleasonton discretionary orders allowing him to withdraw if he felt it was necessary to do so. By 5:00 p.m., Pleasonton’s command had been fought out, and upon learning that Confederate infantry was filtering onto the battlefield, Pleasonton exercised that discretion. Concluding that his men had done enough for one day, Pleasonton sent one of his staff officers, Captain Frederic C. Newhall of the 6th Pennsylvania, to Buford with orders to withdraw from the field. Newhall found Buford “entirely isolated from the rest of the command under Pleasonton…but paying no attention and fighting straight on.” Buford later wrote that once the firing ceased on Gregg’s front along Fleetwood Hill, “I was ordered to withdraw. Abundance of means was sent to aid me, and we came off the field in fine shape and at our convenience. Capt. [Richard S.C.] Lord with the 1st U.S. came up fresh comparatively with plenty of ammunition and entirely relieved my much exhausted but undaunted command in a most commendable style. The engagement lasted near 14 hours.”

Covered by the fresh men of the 1st U.S., which supported the artillery most of the day, and by the men of Ames’s infantry brigade, Buford withdrew across Beverly’s Ford at a leisurely pace. Newhall, who communicated the order to retreat to Buford while the Kentuckian watched the charge of the 2nd U.S., recalled that Buford himself “came along serenely at a moderate walk.” Buford then climbed the knoll above the river and joined Pleasonton and a large group of officers to observe the final act of the day’s drama as the sun dropped. Pleasonton later noted, “General Buford withdrew his command in beautiful style to this side, the enemy not daring to follow, but showing his chagrin and mortification by an angry and sharp cannonading.” At about 9:30 p.m., Pleasonton scrawled a note to Hooker. “I did what you wanted, crippled Stuart so that he can not go on a raid,” claimed Pleasonton, even though the declaration was untrue. “My own losses were very heavy, particularly in officers. I never saw greater gallantry…exhibited then on the occasion of the fierce 14 hours of fighting from 5 in the morning until 7 at night.”

Their withdrawal perplexed Buford’s tired but unbowed troopers. “Our cavalry fell back across the river that night. It was a mystery to the boys why they fell back,” wrote a New Yorker. Pleasonton reported to Hooker, “Buford’s cavalry had a long and desperate encounter, hand to hand, with the enemy, in which he drove handsomely before him very superior forces. Over two hundred prisoners were captured, and one battle flag. The troops are in splendid spirits, and are entitled to the highest praise for their distinguished conduct.” The corps commander later reported Buford’s loss at 36 officers and 435 enlisted men killed, wounded, and missing; total casualties in Buford’s division were 471, more than 50 percent of the total Union casualties of 866. The 6th Pennsylvania suffered the largest loss, 108, including 8 officers. The 2nd U.S. Cavalry suffered 66 killed or wounded out of 225 present for duty during the day’s fight. In addition, a great number of horses were killed or wounded in the fierce fighting, leaving many troopers dismounted. “The proportion of horses killed on both sides in this almost unexampled hand to hand cavalry battle was very large,” reported a newspaperman.

John Buford had every reason to be extremely proud of the performance of his Regulars that day. “The men and officers of the entire command without exception behaved with great gallantry,” wrote Buford. His men acquitted themselves well, matching their foe charge for charge. “No regiment engaged that day on the Union side had more of it than ours,” proudly proclaimed a member of “Grimes” Davis’s 8th New York Cavalry. “It was first in and last out in our division. It was not later than 4:30 a.m. in going in, and was rear-guard at the Ford.” Buford singled out a few officers for commendation, including his protégé, Captain Wesley Merritt. Finally, he praised two captains of Pleasonton’s staff, Ulric Dahlgren and Elon Farnsworth of the 8th Illinois, for their work during the great fight.

When Duffié’s division finally arrived, Gregg withdrew about a mile and realigned his position to connect with Buford’s northern attack, which was raging on Yew Ridge. Most of the Confederate artillery was concentrated on Fleetwood Hill, and Hampton’s and Jones’s brigades shifted to meet the Union threat.158 As Gregg prepared to pitch into the fight once again, Pleasonton ordered the Pennsylvanian to disengage and withdraw. Russell’s infantry covered Gregg’s retreat. The infantrymen had spent the day pinning down Robertson’s brigade, preventing the North Carolinians from reaching the battlefield before the fighting ended. “While Pleasonton was defeated at Brandy Station, he made a masterly withdrawal of his forces,” remembered an admiring Virginian. Stuart noted that Buford’s attack on the northern end of Fleetwood Hill “made it absolutely necessary to desist from our pursuit of the force retreating toward Kelly’s particularly as the infantry known to be on that road would very soon have terminated the pursuit.” Thus ended the largest cavalry fight ever seen in the Western Hemisphere.

The day’s fighting represented a will-o-the-wisp of lost opportunities for David Gregg, a veritable litany of “what if’s.” His command suffered severe casualties. A brigade commander and 2 regimental commanders were wounded or missing, a third field-grade officer wounded, 2 line officers killed and 15 wounded, 18 enlisted men killed, 65 wounded, and 272 missing. His men captured 8 commissioned officers and two sets of colors. Gregg noted, “The field on which we fought bore evidence of the severe loss of the enemy.” He singled out Wyndham and Kilpatrick for particular praise and commended Captain Martin’s artillerists for their valiant stand.

At the same time, he squarely and unambiguously placed the blame for his failure to carry Fleetwood Hill on Duffié, both for delaying his crossing and for the Frenchman’s tardiness in arriving on the battlefield. When he realized that the whole Confederate cavalry force lay in front of him, Gregg should have called for Duffié’s division immediately. He should have used the Frenchman’s division as the hammer to drive Stuart’s surrounded troopers against the anvil of Gregg’s division, holding the high ground on Fleetwood Hill. He failed to do so, and the opportunity to destroy Stuart’s command slipped away. The same opportunity would not present itself again.

For his part, Stuart described the fight for Fleetwood Hill as “long and spirited.” He generally praised all of his brigade commanders, singling out Jones and Hampton especially. At the same time, he damned Robertson for failing to delay Gregg’s advance. Finally, he heaped particular praise on Henry McClellan, for without the enterprising major’s help, Fleetwood certainly would have fallen and the outcome of the battle would have been very different indeed.

In return, Robert E. Lee praised Stuart. On June 16, after reading Stuart’s report, Lee wrote, “The dispositions made by you to meet the strong attack of the enemy appear to have been judicious and well planned. The troops were well and skillfully managed, and, with few exceptions, conducted themselves with marked gallantry. The result of the action calls for our grateful thanks to Almighty God, and is honorable alike to the officers and men engaged.” Lee evidently did not realize just how close his cavalry corps had come to being completely destroyed that day; if he did, he did a good job of salving Stuart’s bruised pride.