THE FIGHT FOR THE STONE WALL

Rooney Lee’s command fell into line to the left of Jones, extending to the north. A stone wall that offered a strong defensive position ran parallel to Lee’s position. The wall, following the lay of the land, was L-shaped. Lee posted dismounted troopers along the wall and others along a ridge directly behind and above the wall. These defensive positions offered excellent fields of fire, affording Lee’s men an opportunity to enfilade the flank and rear of the Union position. The determined Confederates awaited the next attack with some of their best troops on line.

Utilizing this strong defensive position, Lee fended off a number of uncoordinated, piecemeal attacks by Buford’s cavalry. The 5th U.S. made the first assault, trying to drive Lee’s men from the stone wall. The 5th, under Captain James E. Harrison, had only three small squadrons that day and was understrength. Keeping one squadron to support a section of Graham’s battery, Harrison dismounted his remaining two squadrons and pushed them forward as skirmishers. Their Sharp’s carbines blazing, the Regulars seized and held a portion of the wall, fending off a number of ferocious Confederate counterattacks. They remained in place until the Regulars completely exhausted their ammunition. Finally, these two hard-pressed squadrons were relieved, and Harrison’s men retired to support Graham’s battery. The 5th U.S. sustained thirty-eight casualties—a high percentage of its small force involved in the fighting—demonstrating the intensity of the fighting for the stone wall.

Emboldened by Harrison’s limited success, Buford decided to commit the rest of the Reserve Brigade. He ordered the Regulars forward, supported by Elder’s battery and Ames’s infantry brigade. Buford deployed the dismounted Regulars in line of battle alongside McClure’s and Devin’s brigades, the infantry regiments protecting the flanks. While the fresh troops were being organized, Buford called up his artillery.

A vigorous artillery duel erupted between Beckham’s and Elder’s guns. Beckham’s guns soon found the range of Elder’s battery and disabled several pieces manned by Batteries B and L, 2nd U.S. Artillery. The counterbattery blasts kept the Confederate artillery occupied, making an assault easier. Now protected by artillery, Buford’s lines surged forward, supported by the deadly fire of the longer ranged rifled muskets of Ames’s infantry. They attacked the wall, but the steady fire of Lee’s dismounted troopers drove them back. A lull settled across the battlefield as the two sides regrouped.

At 11:30 a.m., Pleasonton, who had finally arrived on the battlefield, wired Hooker: “All the enemy’s force are engaged with me. I am holding them until Gregg can come up. Gregg’s guns are being heard in the enemy’s rear.” Buford’s tired horse soldiers had been fighting constantly since dawn. Although Gregg’s attack was supposed to have been coordinated with Buford’s, Buford had fought alone for nearly six hours.

Nobody had expected a battle of such magnitude, but neither side was willing to quit. Both Stuart and Buford used the lull to redeploy and to recover dead and wounded comrades. At that moment, as Stuart prepared for a full-scale counterattack, the sound of fighting to his rear shifted his attention away from Buford. Finally, at about 11:30 a.m., as one member of the 8th New York recorded in his diary, Buford’s men “heard the booming of distant cannon which told us that Gen. Graig [sic] had arrived from Kelly’s Ford and was engaging the enemy.”

Hearing Gregg’s guns, Buford “resolved to go to him if possible.” With that goal in mind, Buford took all of his force, except for the 5th U.S., which anchored the right and supported Graham’s battery.

The men of the 124th New York marched to the sound of the guns. “As we moved forward, wounded men began to straggle back past us,” recalled a New York infantryman. “Some of these were on horseback, others with pale faces and blood-stained garments came staggering along on foot, and occasionally one was borne hurriedly by on a stretcher, or in the arms of, apparently tender-hearted, but really cowardly, comrades. A little farther on we began to pass over, and saw lying on either side of us, lifeless bodies of men, dressed, some in grey and some in blue, which told unmistakably that the tide of battle was with the Union line.” Steeled, the New York infantrymen formed line of battle and prepared to meet the enemy. They finally drove off the dismounted Southerners after a fierce twenty-minute engagement.

“Both parties fought earnestly and up to 12 o’clock the enemy held his position,” observed one of Buford’s Hoosiers, “but after that hour saw fit to fall back.” Late in the morning, Alfred Pleasonton finally came across the Rappahannock River and established his headquarters in Mary Emily Gee’s large brick house near St. James Church. A second front was about to break out. The brute force of Gregg’s attack on Fleetwood Hill was about to crash onto Stuart’s headquarters with the savage power of a tidal wave.

Climax on Fleetwood Hill

Brigadier General David M. Gregg had not had an easy time of it. Because of the long march from the Warrenton vicinity, Alfred Duffié’s division had stopped to rest for a while and then pushed on. The Frenchman then turned onto the wrong road to Kelly’s Ford, a poor decision for an officer who had spent time in the area. His division was nearly three hours late arriving at Kelly’s Ford, where Gregg sat and waited impatiently. Finally, some time between 5:00 a.m. and 6:00 a.m., Duffié appeared, after taking nearly five hours to cover five miles. The crossing at Kelly’s Ford had not gone well. Gregg’s crossing was to have coincided with Buford’s. However, because Duffié’s division was late to the rendezvous, the entire crossing had been delayed for several hours. When Gregg’s skirmishers finally got across the river, they unexpectedly found men from the green North Carolina brigade of Brigadier General Beverly H. Robertson picketing the ford. Like Buford, Gregg was surprised to find Confederate resistance; Pleasonton’s faulty intelligence also failed to disclose the presence of Rebel pickets at Kelly’s Ford. Gregg’s men captured the Southern vedettes before they could spread word of the Yankee approach, and the Pennsylvanian’s column finally splashed across the Rappahannock. He left the 4th New York behind to guard the ford.

General Robertson’s brigade was made up of two large but completely inexperienced regiments, which were patrolling the area immediately surrounding Kelly’s Ford. When Robertson learned that Yankee troopers were moving on his main body, he sent word to Stuart of the Yankee advance. Robertson was an 1849 West Pointer. He had spent his entire Regular Army career in the 2nd Dragoons on the western frontier. Robertson served under Brigadier General Turner Ashby in the Shenandoah Valley and took command of Ashby’s brigade after the legendary cavalier was killed during Jackson’s 1862 Valley Campaign. He did well in that position, besting John Buford in the final engagement at Second Bull Run, but Stuart relieved him of command shortly thereafter. Stuart despised him and once described Robertson as the “most troublesome man in the Army.” Stuart thought that he had rid himself of Robertson by banishing him to North Carolina, but his untested brigade was summoned to Culpeper for the forthcoming invasion of the North.

Robertson later claimed that Stuart had ordered him to retreat from Kelly’s Ford to Fleetwood Hill, leaving the road to Brandy Station open for the Yankee advance. Stuart then countermanded the order to retreat and directed Robertson to march his command back to the Kelly’s Mill Road position to block the Union route of advance. His North Carolinians immediately encountered Union skirmishers. “Just then the enemy’s line of skirmishers emerged from the woods,” claimed Robertson, “and I at once dismounted a large portion of my command, and made such disposition of my entire force as seemed best calculated to retard their progress.”

Robertson shortly discovered that Gregg had flanked his position and that the blueclad horsemen were rapidly moving toward Stuart’s main position. “I therefore determined to hold the ground in my front should the infantry attempt to advance upon the railroad, and placed my skirmishers behind an embankment, to protect them from the artillery, which had been opened from the woods,” proclaimed Robertson in defense of his actions. Robertson did little else to check the Yankee advance, which proceeded largely unhindered. “Brigadier-General Robertson kept the enemy in check on the Kelly’s ford road but did not conform to the movement of the enemy to the right, of which he was cognizant,” wrote Stuart, “so as to hold him in check or thwart him by a corresponding move of a portion of his command in the same direction. He was too far off for me to give him orders to do so in time.”

Robertson claimed that he failed to hinder Gregg’s advance because he was trying to check Russell’s infantry. He further alleged that his small brigade was an insufficient force to hinder the Yankee advance, so he did not even try to block Gregg’s march. His North Carolinians spent the balance of the day jousting with Russell’s infantry near Kelly’s Ford. They played no role at all in the great cavalry battle raging just a few miles behind them. Their casualties that day totaled four horses killed.

Robertson’s failure exposed the Confederate flank to attack and left Fleetwood Hill completely uncovered. Undisturbed by the North Carolinians, Gregg’s Federals enjoyed a pleasant, though slightly longer, march to Fleetwood Hill. While Gregg could plainly hear Buford’s guns roaring at St. James Church, he took a longer, more roundabout route instead of brushing Robertson out of his way and marching immediately to the guns over the shortest overland route. This decision permitted Stuart to concentrate the fury of his entire command on Buford. As Gregg marched, Pleasonton sent a galloper to him, informing the Pennsylvanian “of the severity of the fight on the right and of the largely superior force of the enemy.” After scribbling a note to Duffié to hurry to Brandy Station, Gregg raced off toward the sound of the guns.

Wyndham’s brigade led Gregg’s advance on the left, followed by Kilpatrick’s brigade just behind and to the right. Sometime around 11:00 a.m., nearly seven hours after Buford’s initial attack, Wyndham’s command finally reached the tracks of the Orange & Alexandria Railroad a half mile from the depot. They spotted a single enemy gun atop Fleetwood Hill and headed straight for it. The Carolina Road, an important route of north–south commerce, ran across the crest of Fleetwood Hill. If Gregg could capture and hold the hill, his position would dominate the line at St. James Church, and Stuart’s force would have to abandon its strong position there. He would also interdict Stuart’s primary route of retreat to Culpeper.

“Grumble” Jones somehow learned of the Yankee advance, perhaps via one of Robertson’s couriers, and sent a messenger to Stuart with this information. Stuart snorted when he heard the courier’s report and responded, “Tell Gen. Jones to attend to the Yankees in his front, and I’ll watch the flanks.” The courier returned to Jones and repeated what Stuart had said. It was Jones’s turn to retort: “So he thinks they ain’t coming, does he? Well, let him alone; he’ll damned well soon see for himself.” This prediction proved correct soon enough.

THE FIGHT FOR FLEETWOOD HILL

Stuart’s personal tent fly still fluttered above Fleetwood Hill as the Yankee wave bore down on it. Two regiments, the 2nd South Carolina and 4th Virginia, had picketed the hill, but Hampton had sent these two regiments to Stevensburg to block Duffié’s advance. Other than a few miscellaneous staff officers and orderlies, the dominant topographical feature of the area lay unprotected. However, one artillery piece—a twelve-pound Napoleon of Captain Roger P. Chew’s battery of horse artillery, which was commanded by Lieutenant John W. “Tuck” Carter—happened to be present. Carter used almost all of his ammunition in the whirling mêleé at St. James Church and pulled back to Fleetwood Hill to refill his limber. Major Henry B. McClellan, Stuart’s capable adjutant, was the highest-ranking officer in the area.

Major McClellan was a transplanted Philadelphian and a first cousin of General George B. McClellan. He was a gifted staff officer who found himself in the right place at the right time this day. Just a few minutes after one of Robertson’s couriers informed him that the Yankees were advancing in force on his exposed position, the head of Wyndham’s column came into view. Seeing the urgency of the situation, McClellan sent a series of orderlies off to warn Stuart. Realizing that if he did not take charge, nobody would, the major sprang into action.

“They were pressing steadily toward the railroad station, which must in a few moments be in their possession. How could they be prevented from also occupying the Fleetwood Hill, the key to the whole position? Matters looked serious!” recalled McClellan. “But good results can sometimes be accomplished with the smallest means. Lieutenant Carter’s howitzer was brought up, and boldly pushed beyond the crest of the hill; a few imperfect shells and some round shot were found in the limber chest; a slow fire was at once opened upon the marching column, and courier after courier was dispatched to General Stuart to inform him of the peril.” The few shots lobbed by Carter’s gun caused confusion in the Federal ranks, and they hesitated a moment to evaluate the threat.

This pause made all of the difference for Gregg’s assault. “There was not one man upon the hill besides those belonging to Carter’s howitzer and myself, for I had sent away even my last courier, with an urgent appeal for speedy help,” observed McClellan. “Could General Gregg have known the true state of affairs he would, of course, have sent forward a squadron to take possession; but appearances demanded a more serious attack, and while this was being organized three rifled guns were unlimbered, and a fierce cannonade was opened on the hill.”

McClellan’s couriers found Stuart directing the fighting at St. James Church. “Ride back there and see what all that foolishness is about,” responded Stuart to the messenger. The repeated urgency of McClellan’s messages combined with the sound of cannonading finally prompted Stuart to pull two of Jones’s regiments, the 12th Virginia Cavalry and the 35th Battalion of Virginia Cavalry, from the St. James Church line and send them to Fleetwood. “The regiment, in the great haste with which it repaired, to the point designated, became much scattered and lengthened out,” recalled a captain of the 12th Virginia. Another member of the same regiment observed, “The enemy gained our rear beautifully but our brigade cleaned them out nicely.”

Stuart also dispatched one of his staff officers, Lieutenant Frank S. Robertson, to find Hampton, with instructions to send a regiment to reinforce Fleetwood Hill. It took a few precious minutes for the Confederate reinforcements to reach the hill. As the head of the small Confederate column reached Fleetwood, it met Carter’s withdrawing gun, now entirely out of ammunition. The vanguard of Wyndham’s attacking column was just fifty yards from the crest of the hill. The two forces crashed together with tremendous force. “With a ringing cheer,” the 1st New Jersey, led by Lieutenant Colonel Virgil Brodrick, “rode up the gentle ascent that led to Stuart’s headquarters, the men gripping hard their sabers, and the horses taking ravines and ditches in their stride.” As Captain William W. Blackford of Stuart’s staff recorded, “There now followed a passage of arms filled with romantic interest and splendor to a degree unequaled by anything our war produced.”

As Gregg approached, he could see the fight raging in the distance. The roar of the artillery grew louder as he rode. The Pennsylvanian ordered his troopers to draw sabers, and “their willing blades leaped from their scabbards, and with one wild, exultant shout they dashed across the field, on, over the railroad, and, with Wyndham at their head, rode over and through the headquarters of Stuart, the rebel chief.” The swarming Federals presented quite a spectacle. “The heights of Brandy and the spot where our headquarters had been were perfectly swarming with Yankees,” recalled Stuart’s aide, Von Borcke, “while the men of one of our brigades were scattered wide over the plateau, chased in all directions by their enemies.”

Stuart sent the rest of Jones’s brigade and the balance of Hampton’s brigade to McClellan’s aid at Fleetwood. The Confederate chieftain rode to the sound of the fighting himself, arriving just behind the 12th Virginia, with Lieutenant Colonel Elijah V. White’s 35th Battalion in tow, close behind. Wyndham’s lead regiment, the 1st New Jersey, briefly took possession of the hill, but the Confederate onslaught crashed into them, driving the Jerseymen back. White led one charging column, while Major George M. Ferneyhough led another. “I ordered 20 men to continue the pursuit from which I was thus reluctantly forced to desist,” reported White, “and returned with the remainder of my command to renew the contest for the possession of the hill.” Ferneyhough’s column likewise slugged it out with the Jerseymen atop Fleetwood Hill, saber blades glinting in the bright sun. The Jerseymen began shoving the Comanches back down the hill. “Stuart’s headquarters were in our hands,” proclaimed a victorious member of the 1st New Jersey, “and his favorite regiments in flight before us.”

Seeing Ferneyhough’s men falling back, Colonel Asher W. Harman of the 12th Virginia tried to provide a rallying point for them at the eastern base of Fleetwood Hill. Meanwhile, elements of the 1st Pennsylvania Cavalry arrived and joined the New Jersey horsemen in the mêleé. “For God’s sake, form! For my sake form!” Harman bellowed as the fighting whirled around him. His men rallied, and Ferneyhough’s retreating troopers joined them. They then charged back up the hill, where Flournoy’s 6th Virginia, just arriving, joined them in the counterattack. “First came the dead heavy crash of the meeting columns, and next the clash of sabers,” recounted a member of the 1st Pennsylvania, “the rattle of pistol and carbine, mingling with the frenzied imprecation, the wild shriek that follows the death blow, the demand to surrender, and the appeal for mercy, forming the horrid din of battle.”

An officer of the 1st Pennsylvania Cavalry remembered, “At one time the dust was so thick we could not tell friend from foe.” “The scene now became terrific, grand, and ludicrous,” recalled a member of the 1st Maryland (Union) Cavalry. “The choking dust was so thick that we could not tell ‘t’other from which.’ Horses, wild beyond the control of their riders, were charging away through the lines of the enemy and back again. Many of our men were captured and escaped because their clothes were so covered with dust that they looked like graybacks.”

Indeed, the heavy dust worked to the advantage of the Federal troopers. Sergeant Charles U. Embrey, Company I of the 1st Maryland, was captured but made good use of his brown shirt. Embrey pretended to be an orderly to a Confederate colonel for a few minutes until he escaped. Sergeant Philip L. Hiteshaw of the same company was captured and escaped because he wore gray trousers.

Perhaps, though, the best story pertains to Major Charles H. Russell of the 1st Maryland. Major Russell found himself cut off from the main body of Gregg’s division, but he rallied fifteen men and went to work. He hid his little command in the woods, and every time a group of the enemy came by, the major dashed at them with three or four men and, when close to them, turned and called out to an imaginary officer to bring up his supporting squadrons from the woods. Then he fell back, always bringing a few prisoners with him. At one time, he had garnered as many as forty or fifty prisoners using this ruse. Finally, the grayclad cavalry charged his position and retook all but fourteen of the prisoners. “The major turned, fired his pistol into their faces, and again called upon that imaginary officer to bring up those imaginary squadrons.” The rebels halted to re-form for the charge, and while they were forming, Russell and his little column slipped away to rejoin their regiment. Russell lost his hat in the mêleé and now wore a captured Rebel cap. “He looked like a Reb. When he returned through the two divisions of Rebel cavalry, he had so many prisoners and so few men that they doubtless mistook him and his party for their own men moving out to reconnoiter.”

Soon the whole plain in front of Brandy Station became a whirling blur of saber-swinging duels, with the two sides mixed promiscuously. Complete victory nearly within his grasp, the taciturn David Gregg caught the spirit of the moment. A staff officer noted that the Pennsylvanian “showed an enthusiasm that I had never noticed before. He started his horse on a gallop…swinging his gauntlets over his head and hurrahing.”

Lieutenant Thomas B. Lucas of the 1st Pennsylvania Cavalry received a vicious saber slash to his head during the chaos. Lucas’s high-spirited mount bolted, and when it hit a muddy spot, Lucas pitched off the horse. The dismounted lieutenant found himself surrounded by enemy cavalrymen. “Kill the Yankee!” demanded one, who crashed his saber down on Lucas’s skull. Fortunately, the blade turned broadside just enough for it to glance off the lieutenant’s skull instead of cleaving it. A few of his men spotted his peril and rescued him with a savage charge, leaving a grateful Lucas with a painful but not serious wound.

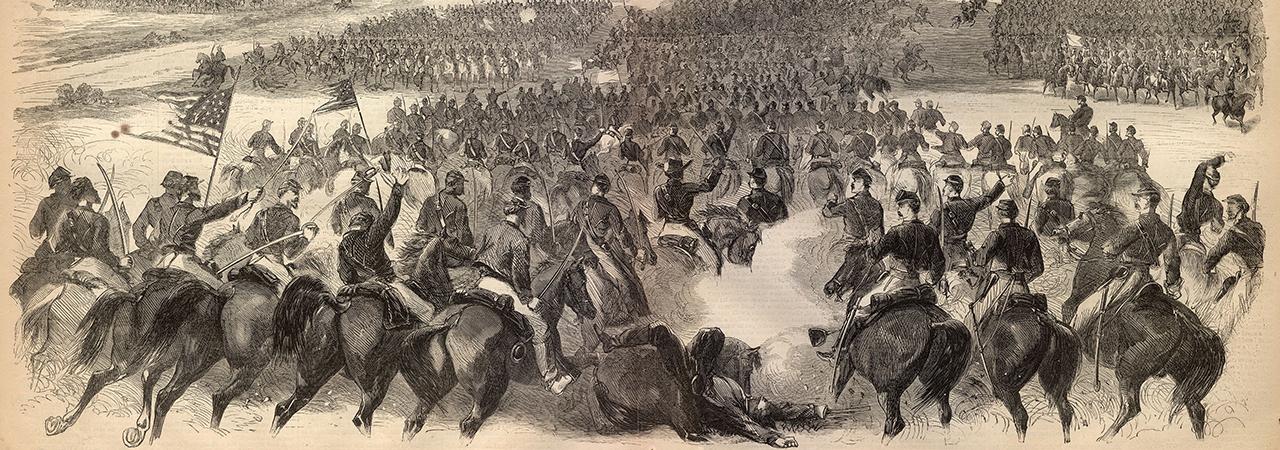

As the Confederates were about to give way, Wade Hampton’s brigade arrived, along with the balance of Jones’s force. With Hampton himself leading the charge, the Southern cavalry pitched headlong into the Yankee cavalry at the top of Fleetwood Hill, and the mêleé resumed. Stuart, following along behind Hampton’s column, could be heard to yell, “Give them the sabre, boys!” Saber charge after saber charge occurred, and the whirling struggle deteriorated into small, isolated fights among pockets of men; all organization disappeared as the horsemen clashed. “What the eye saw as Stuart rapidly fell back from the river and concentrated his cavalry for the defense of Fleetwood Hill, between him and Brandy,” recalled a Confederate staff officer, “was a great and imposing spectacle of squadrons charging in every portion of the field—men falling, cut out of the saddle with the sabre, artillery roaring, carbines cracking—a perfect hurly-burly of combat.”

Gregg brought up a battery, Captain Joseph W. Martin’s 6th New York Independent Battery, which deployed in the fields just in front of Fleetwood Hill. From there, Martin’s guns greatly harassed the Confederates, taking a toll on the unsupported Confederate troopers using the crest of Fleetwood Hill as their base of operations. “The gallant fellows at the battery hurled a perfect storm of grape upon the Comanches” of the 35th Battalion of Virginia Cavalry.

Finally growing weary of the Yankee artillery, Lieutenant Colonel White ordered his 35th Battalion to charge the battery, making its way through a perfect storm of shot and shell. The unit’s historian recorded, “[W]ith never a halt or a falter the battalion dashed on, scattering the supports and capturing the battery after a desperate fight, in which the artillerymen fought like heroes, with small arms, long after their guns were silenced. There was no demand for a surrender, nor any offer to do so, until nearly all the men at the battery, with many of their horses, were killed and wounded.” Martin later reported, “Of the 36 men that I took into the engagement, but 6 came out safely, and of these 30, 21 are either killed, wounded, or missing, and scarcely one of the them will but carry the honorable mark of the saber or bullet to his grave.”

White and a few of the Comanches attempted to turn Martin’s guns on the Yankees, but they received no support, and a Federal counterattack loomed. Captain Hampton S. Thomas of the 1st Pennsylvania Cavalry, one of Gregg’s staff officers, found two companies of the 1st Maryland Cavalry and led them forward to rescue the guns. Joined by other nearby Federals, the Marylanders charged down the hill. Seeing a wall of blue descending on him, White pulled back, leaving the guns for the Yankees.

Meanwhile, parts of McGregor’s and Chew’s batteries arrived on Fleetwood Hill, near the Carolina Road. Sections of the 1st New Jersey Cavalry still occupied a spur of Fleetwood Hill and, pressed by Jones’s cavalry, had no route of retreat available to them. The Jerseymen had to hack their way through the Confederate guns in a scene reminiscent of the fight at St. James Church. “The unexpected suddenness of this movement seemed to paralyze us all,” recalled one of McGregor’s section commanders, “friend and foe alike, for the enemy passed at a walk, accelerated to a trot, and did not design to fire upon or charge us, or attempt to make us surrender.” As soon as their shock wore off, one of the gunners cried out, “Boys, let’s die over the guns!”

“Hart’s men beat them with their gun sticks,” recalled an officer of the Cobb Legion Cavalry. “Scarcely had our artillery opened on the retreating enemy from this new position than a part of the 1st New Jersey Cavalry, which formed the extreme Federal left, came thundering down the narrow ridge, striking McGregor’s and Hart’s unsupported batteries in the flank,” recalled Captain Hart, “and riding through between guns and caissons from right to left, but met by a determined hand to hand contest from the cannoneers with pistols, sponge staffs, and whatever else came handy to fight with. Lieutenant-Colonel Brodrick, commanding the regiment, was killed in this charge, as also the second in command, Major J.H. Shelmire, who fell from a pistol ball, while gallantly attempting to cut his way through these batteries. The charge was repulsed by the artillerists alone, not a solitary friendly trooper being within reach of us.” Captain Henry W. Sawyer of the 1st New Jersey was severely wounded and left on the field for dead. Sawyer survived and ended up a prisoner of war at Richmond’s notorious Libby Prison.

The Jerseymen charged three times against an enemy force four times larger. “The fighting was hand to hand and of the most desperate kind,” recounted Lieutenant Thomas L. Cox of the 1st New Jersey. “Col. Brodrick fought like a lion. Wherever the fight was the fiercest his voice could be heard cheering on his men, and his revolver and sabre dealing death to the enemy around him. His bravery and daring conduct is the admiration and praise of everyone in the division. His horse was killed in the first charge, but he immediately mounted another and was soon leading his regiment.” The stout Confederate counterattack drove off the Jerseymen, who had to leave their mortally wounded colonel behind. He died a few days later while in Confederate hands.

Three different times during this mêleé the enemy captured the guidon of Company E of the 1st New Jersey, and twice the Jerseymen retook it. “The third time, when all seemed desperate, a little troop of the First Pennsylvania cut through the enemy and brought off the flag in safety.” As the Jerseymen retreated, the Confederates charged their rearguard, but the next unit in line checked their assault, saving the rear of the Federal column. Wyndham fell, badly wounded in the leg. The Jerseymen withdrew with 150 prisoners in tow. With that, the determined Confederates regained possession of Fleetwood Hill.

The regimental historian of the 1st New Jersey Cavalry pointed out that “men and horses had been fighting for over three hours and were now utterly exhausted.…There were not a dozen horses that could charge—not a man who could shout above a whisper.” The Jerseymen went into battle with 280 officers and enlisted men and, in a span of three hours, lost 56, including their regimental commander and his second-in-command. They hung on gamely, nursing the fading hope that Duffié’s men would come up from Stevensburg to tip the balance in the fight for Fleetwood Hill.

In response, Gregg ordered Kilpatrick to attack with his brigade to the right of Wyndham, and its charge caused the Confederate force to “break…all to pieces…[and it] lost all organization and sought safety in flight.” As Kilpatrick’s troopers struggled up the crest of Fleetwood Hill, things looked bleak for the Rebel cavalry. Kilpatrick rode over and ordered the 10th New York Cavalry, which was coming up to support his attack, to draw sabers and charge into the Confederates atop Fleetwood Hill. “The rebel line that swept down on us came in splendid order, and when the two lines were about to close in, they opened a rapid fire upon us,” recalled a member of the 10th New York Cavalry. “Then followed an indescribable clashing and slashing, banging and yelling.…We were now so mixed up with the rebels that every man was fighting desperately to maintain the position until assistance could be brought forward.” Lieutenant Colonel William Irvine of the 10th New York had his horse shot out from under him and was pitched to the ground. Irvine fought alone until the Southerners overpowered and captured him. Major Matthew H. Avery, who succeeded Irvine in command of the regiment, fondly recalled, “I never saw so striking an example of devotion to duty. He rode into them slashing with his saber in a measured and determined manner just as he went at everything else, with deliberation and firmness of purpose. I never saw a man so cool under such circumstances.”

Captain Burton B. Porter of the 10th New York tried to rally enough men to free Irvine, but there were not enough available. “Every man had all he could attend to himself,” recalled Porter, who found himself with only two or three troopers available. Just then a big Rebel bore down on him with saber raised. “I parried the blow with my saber,” he recounted, “which, however, was delivered with such force as to partially break the parry, and left its mark across my back and nearly unhorsed me.” One of Porter’s men came to his rescue and dismounted his assailant. “It was plain that I must get out then, if ever,” observed the captain while a squadron of enemy cavalry bore down on him. Porter dashed up onto the railroad tracks at the foot of Fleetwood Hill, safely out of their reach. The New York captain saw another officer of his regiment shot down in front of him before making good his escape.

A bold charge by the Cobb Legion, supported by Colonel John Logan Black’s 1st South Carolina Cavalry, cleared the area for the deployment of the Confederate guns. Jeb Stuart dashed up, doffed his hat, its long, black ostrich plume waving, and cried out, “Cobb’s Legion, you’ve covered yourselves with glory, follow me!” and led the charge himself. Colonel Pierce M.B. Young, commander of the Georgians, noted in his report, “I immediately ordered the charge in close column of squadrons, and I swept the hill clear of the enemy, he being scattered and entirely routed. I do claim that this was the turning point of the day in this portion of the field, for in less than a minute’s time, [a Federal] battery would have been on the hill.” Stuart’s staff officer, Heros von Borcke, turned to Stuart and said, “Young’s regiment made the grandest charge I see on either continent.” McClellan called this movement “one of the finest which was executed on this day so full of brave deeds.”