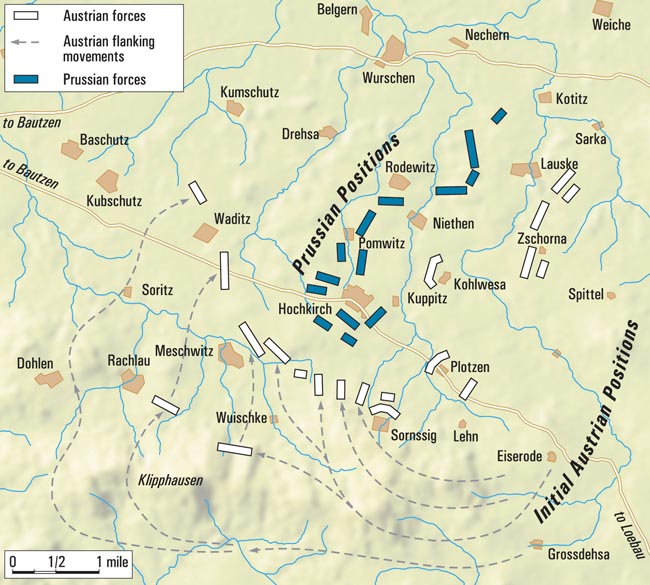

In the meantime, the main column reached its destination—the jumping off point before the Prussian camp—without interference. Laudon, over by Wuischke, was also moving into attack position. Here the marshal’s men stood in three varying columns of troops, waiting for sound of the bell announcing 0500 hours. On his end of the Austrian formation, Arenberg took his men past the Stromberg towards Laskau, where the bluecoats had their big battery on the left of Rodewitz. The muzzles were aiming into the woods, in case the Austrians should try something. Arenberg was waiting for his cue. This would be when he had evidence (either visual or otherwise) that Daun’s main body had already overwhelmed the Prussian right between Hochkirch and the battery. Plenty of such evidence would be forthcoming.

Between these bodies, with support from auxiliary forces—these to apply pressure all along the Prussian camp—there was a good chance of overwhelming the foe. The attack was calculated to hit when it was least expected, adding to its effectiveness. The auxiliary forces were meant to annoy, divert, and confuse the Prussians to keep them off balance. The design for the small columns was necessitated by the thick woods and the geographic position, which would have made utilizing the entire army as a single unit impracticable.

General O’Donnell was to lead such an auxiliary mission in the rear of the Prussian position north of Hochkirch itself; his command (like Laudon’s) consisted largely of cavalry, 20 squadrons of horse and only two regiments of infantry. O’Donnell’s command consisted of: 36th and 38th Infantry; 19th Dragoons, 4th and 33rd Cuirassiers and the old command of Luchessi, now led by Lt.-Gen. Buccow. Next in line was Laudon’s men and then Daun’s. To the right of the latter, again more to annoy than to attack, a force of 600 infantry, supported by the 1st and 38th Dragoons under Wiese, next to Field-Marshal Colloredo with the 7th, 26th, one battalion of the 57th Infantry, as well as the Mainz regiment supported by the 12th Cuirassiers, was to attack. Arenberg was next in line, and north of him stood Buccow with 37 squadrons of cavalry. He had the unique distinction of leading an all cavalry assault column in the impending action.

The main pressure had to be exerted by Daun/Laudon against the Prussian positions in and about Hochkirch. Here depended the whole success or failure of the proposal. Far to the rear, Baden-Durlach, responding to orders, was moving up to do battle with Retzow out beyond the water near Weissenberg. The army was waiting only for the jump off.

In contrast, the greater portion of the Prussian army was still in bivouac, the men little suspecting the unpleasant surprise which the enemy was preparing for them. In the thick woods amid the formidable undergrowth, the way was now sufficiently clear to provide no obstacle to the attackers. The Prussians had suspicions, but nothing more.

Before the hour of 0500 on that fateful morning, October 14, Daun’s men reached their assigned attack points. A number of Austrian “deserters” made their way to the Prussian forward posts and were admitted to the lines. When the time came, they accessed weapons and started firing at their new “friends.” These men had a tough job. The main body was to strike and roll over the Prussian posts between the big battery and Hochkirch, just where the enemy’s army was at its strongest in terms of terrain and the additional man-made obstacles. On the left, the troops of Laudon were preparing to pounce upon Ziethen’s unsuspecting cavalry (he had three battalions, 15 squadrons, holding the westernmost end of the Prussian line). As for Arenberg, he was poised before the Prussian left, anchored between Kotitz and Laskau.

In spite of the surprise which the Austrians pulled off, there was nothing that could be called a rout. This fact is directly attributable to the tough training that these soldiers of Prussia were subjected to to make them fierce in battle. The looked for thrashing might have been expected in a lesser army, but Frederick’s men, though brought out prematurely in a morning surprise, formed and fought a pitched battle, with more order than could have been expected under the circumstances. Perhaps the conditions were better than many histories of the battle have implied. Certainly there had been deserters from Daun bringing in reports that the Austrians were moving, and we have already observed the hussars had put out the alarm.

The artillery teams of the battery in front of Hochkirch had gone to post about 0300 hours that morning, waiting for the usual demonstration of enemy outparties. Generally for about a week, the enemy had been sending Croats/Pandours out to harass the bluecoats. Elsewhere in the predawn, there were still pickets, outparties, and mounted sentinels about, so that when the battle began the Prussians at first believed it was merely the usual demonstration. The horses of the Prussian cavalry stood saddled through the night, waiting for the horsemen. Seydlitz apparently “bypassed” the king’s directive by unsaddling his horses and then shortly after countermanded the order. This was a violation of Frederick’s stand down order. On the southward end of the big battery and right flank stood the duly vigilant guard forces. Under such circumstances, the Prussian army could hardly have been caught napping (if readers will pardon the pun).

Meanwhile, out in the thick woods, several men who were less than enthusiastic about the Austrian cause picked this very dark night on which to desert. As the rank-and-file soldiers were not privy to the attack scheme, these men could provide little help beyond telling the Prussians the army was on the move.

When the appointed time drew near, the king’s men thought there might not be the usual showing at all. Then some men from Angelelli’s Free Corps, catching the foe at a glimpse advancing through the woods, opened a rapid, deliberate musket fire upon them, which precipitated the opening of the battle. A confused struggle broke out then and there, and raged on in the thick brush for ½ hour or more, the Prussian outparties all the while being gradually forced to give ground under the weight of numbers from their forward positions. This fight was assumed back at camp to be nothing more than the usual, but instead of tapering off after a time, the clash became more intense and got closer.

The artillery teams stationed south of Hochkirch turned their guns towards the southern end of the outworks and fired, concluding obviously if the enemy were in strength then they would have artillery to reply with. Receiving no reply, the batteries were then swung round at the direction of the fighting. They were taken under fire and promptly overrun by Laudon’s advancing troops, who had come forward upon their rear from Meschwitz and Waditz. One of our great contemporary historians, Georg Tempelhof, present near the Great Battery, managed to get off about “fifteen rounds before I received a blow that knocked me senseless.” Daun was simultaneously sweeping in from the front. Shortly the entire section of the Prussian line there was in enemy hands, and some of the bluecoats had yet to realize that a battle was raging at all.

The Austrians now burst through the undergrowth on all sides of the camp, and a confused, mostly hand-to-hand struggle was quickly taken up. The Prussians, at last awake, made a fierce, determined resistance, but finding themselves on the southern end all but surrounded by the far more numerous Austrians, they had to pull back. This extrication was accomplished only with the use of the bayonet, and the troops paused a short distance to their rear. Ziethen, by now mounted and ready, charged the surging Austrian formations, broke some, and before they could retreat, killed a great many of the enemy. But Ziethen’s stamina could not stay, and he likewise drew back. The cavalry, to their credit, did do their best here. The earlier Prussian debâcle at Kolin, in sharp contrast, had seen the Prussian horse very ineffective.

At length, the Austrians, although they did indeed have to earn their success the hard way, aided by superior numbers, pressed the thinning Prussian line back upon the battery, which they finally took. The grenadiers of Wangen and Heyden were unable to stem the relentless Austrian advance. Heyden led grenadiers from the brave 19th and the 25th infantry, along with Wangen’s men. These two units, in direct support of the battery, fought very hard, some of it in hand-to-hand combat, before yielding to the inevitable. A counterattack drove them back out, though Daun, coming up with overwhelming reinforcements, again pressed the foe back and retook his prize. The battery changed hands many more times before the whitecoats, in irresistible mass, were finally able to push Frederick’s men beyond reach and that important post was irretrievably lost to them.

Meanwhile, Major Simon von Langen, with the 2nd battalion of the 19th Infantry (General Karl Friedrich Albrecht of Brandenburg-Schwedt), seeing the general tide of the fight edging back upon Hochkirch, flung himself and his men into the place and took post in the Church/Churchyard, strengthening it as quickly as he could combat the enemy. His arrival was fortuitous for Lieutenant von der Marwitz, originally commanding a squad at the churchyard. Marwitz, desperately wounded in the chest, continued to exercise command until Langen’s arrival. The stroke against Hochkirch had indeed been a surprise. Marwitz was captured and subsequently died in captivity.

Saldern’s 15th Infantry, on the Pommritz Heights, lost heavily in killed/wounded and prisoners. 618 men, plus 13 officers, “fell.” Other units were in deep trouble as well. A thick fog had formed and the dawn was breaking in dense darkness. Hochkirch itself was soon on fire, whether started deliberately by the Prussians or however ignited is not clear, which lit up the battle now raging about it. The attackers poured into the village, through the narrow streets, quickly overlapping the barricaded defenders. Langen’s men fired obstinately against the Austrians who charged the churchyard wall, while other Prussian forces outside recoiled and regrouped to come on again and retake Hochkirch. The enemy kept pouring in new troops, reaching a strength of seven full regiments.

The king tried to reassure his troops that the sound of the fight was a mere Croat exercise, but Captain Karl Ludwig von Troschke’s intelligence that the redoubt south of Hochkirch was already in enemy hands and their advance was pressing on relentlessly took him aback. About then, one of 23rd Infantry (Forcade’s) battalions launched an unsupported attack, but after an initial burst, it had to beat a hasty retreat when the Austrians threatened to overlap it. Langen kept his men steady and riddled those white-uniformed opponents with heavy musketry. Nevertheless, the Austrians soon had burning Hochkirch cleared of Prussians round the churchyard, then redoubled their effort to seize it as well. The converging Austrian blows naturally forced masses of Prussian troops into the narrow streets of Hochkirch. This included men outside of Langen’s command area, although, with graphic detail, the streets were said to be running in rivers of blood. The crowding was so bad that the bodies of the dead were still held in their upright postures.

Steady concentrated fire swathed the attacking line, but the intruders, nothing daunted, kept exerting pressure against Langen’s position. Langen might have done more had his ammunition been more plentiful (remember the Prussian army was not expecting the surprise attack). But with the men down to a few rounds apiece in many cases, he had no option but to order his troops to abandon their hotly contested post and cut their way through the thickly-packed ranks of Daun’s men, who had advanced, kicking and clawing for every yard, past the place. A few of the Prussians from the churchyard did indeed make it back to their own lines, clearing the way largely with the bayonet. But the greater majority were killed in a hopeless struggle with an enemy too numerous to beat, and there and then got cut down; Major Langen, a fine Prussian officer with a potential for a great future, being mortally wounded himself—going down with 11 distinct wounds.

Frederick had his suspicions, meanwhile, but so dark was the dawn and so thick the fog that even Keith, who was present on that side, was not aware of the intensity of the fight. For fully an hour, while the action escalated into a full-fledged battle, Keith and all concerned there hastened to find out what was really going on. Most of the army was by then aware that an unusually severe struggle was raging on the southern end of the camp, but just how involved was the struggle was not known. By 0600 hours, the Prussians had been forced to give up Hochkirch, but strong reinforcements from the as yet unengaged center and left were reaching the sight. These revitalized the surprised and fought out defenders, and made possible tough counterattacks which forced Daun to fall back at some points momentarily.

Retzow’s 6th Infantry lost 335 men in one of these counterattacks west of Hochkirch, with its participating neighbors, the 20th of Bornstedt and Wedell’s 26th, lost 500 men, respectively. Von Geist was mortally wounded in a counterattack trying to retake the big battery. Meyernick’s 26th Infantry was attacked by Austrian cavalry, and then launched an attack northwest of Hochkirch. The regiment had suffered severely; only 150 men survived to cut their way through the surging Austrian mass. The cavalry had its share as well. Baron Schönaich’s 6th Cuirassiers, in a devastating counterattack, hacked up the Austrian 44th Infantry, taking 500 prisoners and a standard.

Ziethen ordered Major-General Krockow to lead these horsemen into an attack against the milling Austrian mass to the south of Hochkirch. Krockow’s 2nd Dragoons stayed put north of Rodewitz. Krockow told the troopers around him that “we must show what kind of people we are.” The Schönaich unit did, as we have observed. The valiant Krockow was mortally wounded in the attack. The foe was just as hard-pressed. The Austrian 44th Infantry (Clerici) was badly used, although it did receive honor as the first Austrian regiment to overrun the battery at Hochkirch. Then Ziethen’s hussars, losing Major Seelen to a battle injury—he had to be taken from the field—were struck by a decisive cavalry charge led by Lacy. The latter, leading three companies of mounted grenadiers, pushed hard against the Prussian flank. Laudon joined in an attack against Ziethen’s faltering command, pressing his Croats from the left against a Prussian line that was beginning to fragment, opening gaps between individual formations that rendered the entire line vulnerable.

Major-General Bredow’s 9th Cuirassiers blunted the advance of O’Donnell’s surging cavalry, forcing it to fall back from the edge of Hochkirch. Pennavaire’s 11th Cuirassiers rolled over O’Donnell’s left, taking three standards. Colonel Wackenitz’s 13th Cuirassiers beat back an Austrian attempt to surround Hochkirch.

The constantly growing Austrian foe would not be denied momentum for long, and they compelled the bluecoats in their turn to retreat. In the far right, Laudon tried again and again to make his way into the Prussian rear, but Ziethen would have none of it. The action between these forces was ferocious. Elsewhere, Keith, getting the sense of what was going on at last, came hurrying forward, toward the battery under Hochkirch. By then, it was Daun’s, though not for long. Keith brought with him whatever bodies of troops could be hastily gathered. Upon awakening, Keith was already apprised of the desperate situation of the battery. He pushed the Kannacker regiment to the front and rode with it, bringing every man he could find.

He knew, whatever else, that battery would have to be retaken, and held if there was to be any hope of gaining the victory. His last words of encouragement for the king read like a story out of a novel. He had a report issued that he would hold out to the last man, and, on a more personal note, “I doubt whether we … [will meet] again.” Keith’s men shoved the enemy out of the battery, but was immediately attacked by a powerful mass of Daun’s surging troops and had to draw back a little, his men paused at that point and waited for aid from other quarters.

Keith had ordered Itzenplitz’ 6th Infantry (about 0600 hours) to retake Hochkirch, behind which he urged up General Kannacker’s 30th Infantry to its support. It would lose half of its men at Hochkirch. At length, the punishing fire from the Austrian guns forced Itzenplitz to fall back upon the supporters, while the Preussen regiment penetrated the village and even reached the churchyard, where Langen was still fighting it out at that moment. After a long wait, and not receiving any direct assistance, Keith had to draw off and leave the battery in the hands of the enemy—for good this time. The Prussian advance, though valiant, was futile. It constituted a patchwork attack rather than an orderly stroke. Keith’s hastily contrived force could hardly hope to sustain itself against an Austrian line that bathed it with concentrated, crashing volleys.

He shoved the Austrians who opposed his retreat out of the way with the bayonet, having been wounded himself twice in the right chest and surrounded by a great number of his dead and wounded men. His groom, John Tebaye, witnessed Keith receive a mortal wound. Keith fell dead right into Tebaye’s arms, who was quickly carried among the retreating mass of Prussians towards the rear. When he did manage to return later to collect Keith’s body for decent funeral, he found all of Hochkirch (even the churchyard, where Langen’s valiant resistance was done) humming with the enemy. He could not reach the site, but the Austrians themselves discovered and buried Keith with honor, General Lacy being prominent in these proceedings. “[Keith] was buried with all the honors of war.”

Meanwhile, Frederick, hearing news that Keith had been repulsed by an enemy who were advancing with unconquerable force, for the first time finally realized just how serious the situation was. He had already dispatched troops to the right to help Keith and his struggling men When word arrived that Keith had been killed, the king ordered Prince Franz of Brunswick and Moritz to take their men and move at once to support the right wing forces engaging the enemy near Hochkirch. Charles of Brandenburg-Schwedt then sped off as well, and the king himself leaped to horse and galloped off to see to the matter himself. The attention of both armies was turning that way. The Prussian infantry packed into Hochkirch’s streets were being frittered away in useless close range fighting and needed a change of direction. Frederick, being the general that he was, realized this as soon as he reached the scene.

The reinforcements from the Prussian center had just approached Hochkirch when the 26-year-old Franz, at the outskirts, had his head sheared off by a cannon shot. His men, jumped as they swept forward, were brought to a grinding halt by concentrated Austrian fire, then, hit by strong enemy formations, they were soon stalling out with heavy casualties. Now a heavy fire fight was opened between the three regiments of Prussians that the king brought forward and the Austrian defenders. In spite of his efforts to press home the attack, Frederick simply could not get the advance going again. The Austrians, forming a front line facing west against the king, more than held their own.

Prince Moritz rode almost directly into the Austrian lines, mistaking the enemy for friendly troops, due to the darkness and his myopic vision. His troops had just been repulsed badly in their attack and were falling back. Moritz, realizing his error, turned and rode off after them, but not before he received a painful wound for his trouble. He was riding a little while after on the road to Bautzen, and was picked up by enemy irregulars before he could receive medical attention.

On the field, Frederick’s hastily assembled units (mostly Wedell’s 26th Infantry), escorted by the king himself, came riding along into the thick of the fighting, with his men at double pace behind. As he steadied the faltering 26th, his horse was shot from under him, seriously enough so that he would have to mount a new charger, after which, he rode on, leaving Hochkirch to the left, but found on reaching the gap the fog clearing off, the enemy massed in huge force in front of the tributary. Laudon finally dislodged Ziethen with heavy pressure, and the Austrians now anchored solidly on Steindörfel, the Bautzen road and Waditz. An Austrian cannon shot exploded close to the king here; he and his entourage were showered with rock and dirt.

Keith’s counterattack came about 0630 hours, but the arrival of Austrian reinforcements (led by Lacy) stemmed the Prussian advance and the battery was left in Austrian hands. That battery was plastering away now at its former owners. There was no option left on this side. Frederick knew he must retire.

The Prussian right had been thoroughly driven in, Ziethen had fallen back and Laudon was now in his place. Everywhere, the king’s troops were facing superior enemy forces. Frederick turned and rode back towards the Prussian center, ordering his men to reform into a closer, more compact body to answer the Austrian blows. The 5th Infantry of Saldern, joining with fragments of additional nearby regiments, formed a patchwork rearguard. This body formed a semi-circle between the Rodewitz road and the Czernabog. Saldern was still being pelted by Austrian cannon. The capable Saldern inspired confidence with his bearing at a moment when others seemed about to lose their’s. Archenholtz says Saldern’s valiant efforts prevented the enemy from taking full advantage of the situation.

This battle position was formed between 0700–0800 hours, so in only a few hours of fighting the Prussian right had been defeated. Major Möllendorf was ordered to the Dresha Height, to occupy it before Arenberg had the opportunity to do so. The king was quick to realize that the dominating rise, above the village, stream and pass, was essential and had to be held against the foe if the position were to be maintained. Möllendorf moved as hastily as he could to the task he had been ordered, and did indeed grab the Dresha Pass before the enemy. Meanwhile, Ziethen, by now having reorganized his troopers, moved his squadrons to the mounds of ground above Kumschütz, Canitz and vicinity, with his front facing Bautzen and Jenkowitz (towards which was the only line of retreat), Kumschütz being at the other end of the rises.

Frederick sent orders to Retzow, still near Weissenberg and not yet committed to serious engagement, to march hastily to join the main body. Retzow had not been entirely ignored, for Baden-Durlach, advancing lethargically from Reichenbach, drew out against him in long lines and actually made a weak attack at about 0730 hours. This was the weakest effort of the whole battle, but even so it did seriously delay the needed reinforcements that Retzow could provide until it was finally dealt with. Even before the attack on the Prussian left, the assault against the right finally ended. None too soon!

Laudon remained dormant after mauling Ziethen—it could have been that he had orders from Daun not to proceed further. The main force of the Austrians, perceiving the crucial position at Dresha occupied by the foe, pushed out to take the key to the battle there on that side.

This assault was supposed to have been launched with cavalry, but seeing the post there well secure, the horsemen withdrew without a blow. Daylight was increasing and the whole field-of-battle becoming visible for the first time. For the rest of the battle, Daun assumed a characteristic static pose on the rises near and at the battery with Laudon opposite; both of these commanders spent the time reshuffling their forces, which had become confused in the sudden attacks. The battle there was winding down, just as the fight for the Prussian center was developing. Arenberg launched his troops in a general attack against the thoroughly awake troops of the Prussian center. His stroke was made in broad daylight, with the bluecoats waiting on him. The Austrian subordinate had been instructed to remain stationary and wait until the action near Hochkirch was over, and only then go forward.

He carried out his orders, but the result was that his attack line quickly bogged down and could go nowhere. With little success to show for heavy losses, Arenberg wisely halted his attack to await the progress of the battle elsewhere. Nearer to the main force, Lacy, Wiese and their men made attacks against the Prussian center from the road/stream in front of Laskau (here the terrain sloped downward as soon as one passed the creek).

Nowhere, though, could the Austrians make any further significant gains, and their losses were negating what progress they were making. It was 0800, and the Battle of Hochkirch was entering its third hour. Frederick’s army was holding post, in spite of heavy losses and spreading confusion. The Prussian king was preparing to retreat through the Dresha Pass, and Doberschütz, for he knew that the battle was lost. But first the enemy’s clutching advance would have to be blunted. The Prussians were now too weak numerically to sally out against the superior Austrian force and so were forced to receive the foe in the manner they chose. In short, Frederick could not, without endangering the safety of his entire army, take advantage of any mistakes the enemy might make. This factor, in combination with the larger numbers of the Austrians, were the major advantages for the Austrians on this day.

The Austrian attacks were concentrated mostly in front—against the final major battery in Prussian hands, at Rodewitz—now the key to the Prussian center. Arenberg, seeing the powerful enemy battery taken now, was preparing to renew his attack when Retzow’s advance (led by General Duke Eugene of Württemberg), four battalions and 15 full squadrons, at last made its presence felt. Retzow had finally escaped from Baden-Durlach’s pinning attack. Eugene headed at once across the brook near Weissenberg and on to the vicinity of Dresha, crossing the stream and shortly reaching Belgern (here he detached a small party to hold that end of the battery) then swung to face the enemy there. His maneuver was crucial.

The little battery formed a salient between the stream and the forces at Kotitz, near where Arenberg was positioned. The latter took the newcomers under fire, and prepared for a fight, but repented as soon as Retzow himself appeared with the main body of his troops. By the time the latter appeared, the sun was up and shining brightly, making long shadows across the battlefield. The time was about 1000 hours. Upon the arrival of his still relatively fresh left wing, Frederick, knowing that there was no sense in subjecting his beaten army to further torture, ordered an immediate withdrawal through the Dresha Pass on Doberschütz. The last Austrian strokes were weaker, indicating that Daun’s men were tiring as well. The armies had been at it for more than five hours by then, so this was certainly understandable. The Prussians disengaged, Arenberg drew back, and the rest was anticlimactic. The firing gradually ceased, and the Battle of Hochkirch was effectively over. It was just past 1015 hours.

Frederick ordered the retreat to Klein-Kammin (some 4 1⁄2 miles northwest of the field). The army made an orderly withdrawal to a position there, preferring that to a general retreat in the full sense of the word. Möllendorf and Retzow played the parts of watchdogs to guard the retreat of the rest of the army. It must have been a bitter pill to swallow for the old veterans, many of whom had never known defeat—apart from Kolin, where the army was by no means decisively beaten. Lt.-Col. Saldern had been instrumental in his efforts allowing time for the extrication. As for Retzow, his efforts at the close of the battle allowed him to be “again taken into the royal favor.” Saldern’s experience really paid off at a critical juncture. He had a mere five battalions and he skillfully maneuvered his troopers by anticipating the shelling of the Austrian guns. “By means of this expedient, Saldern accomplished his withdrawal by zig-zag movements.” Saldern knew it would take a few minutes to resight the guns.

The king himself was in a state of virtual shock. Mentally, he was haunted by the knowledge that he was largely responsible for the disaster. The regiment of Wedell, panicked by the view of Prinz Franz’s decapitation, had been personally rallied by his Majesty. Now the subaltern Bareswich approached Frederick, in company with 30 soldiers from the 26th Infantry. He presented three enemy colors to the great leader, whose sash was turned by the blood from his beloved mount. His coat tattered, the Order of the Black Eagle ripped away, and general exhausted statements to General Retzow’s son, an aide-de-camp, that he “regret the number of brave men who have died … [at Hochkirch]” leave a very human impression of a troubled man. Also, unlike the defeat at Kolin, which was more like a battle started that turned sour due to unanticipated problems, that of Hochkirch was out of control from the beginning.

Daun’s army, looking around from its positions on the hills more than 5 1⁄2 miles long, inexplicably chose not to interfere with this movement, but was a mere passive spectator to the march. Daun spent the time reforming and reorganizing his men, allowing a golden opportunity to do something really significant against the enemy. His passivity negated the victory. He allowed Frederick to sneak away, just when he had him. As the king freely admitted in his History of the war, “Daun … did not appear to have gained success.” None of this prevented the marshal from informing Vienna of his “great victory.” Daun, about 1100 hours, sent one of his adjutants, Major von Rothschütz, speeding towards the Austrian capital with the news. Indeed, a pursuit right there would either have thrown the Prussian army into a disorganized retreat or else forced it to fight under circumstances so unfavorable that the issue would be hardly in doubt. Lest we forget, another defeat must have uncovered both Silesia and Saxony to reconquest.

It was not to be. Between Kreckwitz on one side and toward Belgern and the stream on the other, Ziethen and some cavalry were shielding the line-of-retreat, the movement being brought off without a hitch. The bluecoats reached their destination easily, and particularly worthy of note was that Seydlitz, although not having had a distinguished day at the battle, at the head of his horse—108 squadrons—covered the movement on Doberschütz.

Daun stayed in camp with his army only a little longer. Shortly the force, which had fought so fiercely for the battlefield, gave it up and retired back on the lines at Kittlitz and Reichenbach. Readers will note this is the opposite of what Daun should have done. He left only a detachment to hold the tortured field.

Thus closed the narrative of the Battle of Hochkirch. It was to be the last victory of Daun over the Prussians led by their king in battle, although he would win a decisive action against General Finck at Maxen a year after. This encounter was a hard-fought battle, but Hochkirch had none of Zorndorf in it. The losses the two armies suffered were the following: Frederick lost approximately 5,381 men/119 officers (5,490 of all ranks) killed or captured; 4,060 wounded/missing; total, 9,450 men, or over ¼ of his manpower. This loss was certainly terrible, as any loss involving human life always is, but nowhere near what could have been expected under the circumstances. In material, Prussian losses were 101 guns (nearly all lost in the two batteries at Hochkirch and Rodewitz), as well as most of their tents and camp equipage.

One of the biggest, most immediate consequence to the king was the loss of Field Marshal Keith. Keith was another of the ilk of men who were like General Winterfeldt, the king’s confidant up until his death in 1757. The body of Marshal Keith was at first gathered up unrecognized among the dead of the Battle of Hochkirch, although Daun and Lacy both recognized the corpse later. Marshal Daun expressed great sorrow over the demise of Keith. The Austrian high command had him buried with full military honors. The Prussian king, on his side, grieved as much as he dared under the desperate circumstances. In 1759, at the order of Frederick, Keith’s remains were belatedly exhumed and brought back to Prussia. He was buried, again with great sorrow, in the Potsdam Garrison churchyard. The fortunes of war had been grim for both sides. The whitecoats suffered a grievous loss on their side as well. The eldest son of Marshal Browne, Colonel Joseph Browne, was killed in this Hochkirch battle. This episode helps cast light upon the large number of Irish officers who frequently served in the armies of Maria Theresa, often in high command situations. What a contrast with the Prussian service! Most of the higher-ranking bluecoat officers, with the exception of men like Keith, were German-born.

Daun’s losses were surprisingly greater. He had about 90,000 men present, and had 5,939 killed/wounded (325 officers and 5,614 rank-and-file), with about a thousand prisoners, and, most shockingly, over 2,500 deserters who left the ranks during the march through the thick woods, making for an aggregate total of 9,500 men, or ⅛ of his force. No doubt a great many of the latter made their way to the Prussian camps, where their stories of large troop movements in the woods had met a mixed reaction before the battle even broke forth.