Although the Mahdi died in June 1885 the fight was continued by his successor, the Khalifa. Between 1885 and 1896, when the reconquest of the Sudan was undertaken by the Anglo-Egyptians.

The Mahdists fought the Italians for the first time at Agordat on 27 June 1890. About 1,000 warriors raided the Beni Amer, a tribe under Italian protection, and then went on to the wells at Agordat, on the road between the Sudan and northern Eritrea. An Italian force of two ascari companies surprised and routed them; Italian losses were only three killed and eight wounded, while the Mahdists lost about 250 dead. In 1892 the Mahdists raided again, and on 26 June a force of 120 ascari and about 200 allied Baria warriors beat them at Serobeti. Again, Italian losses were minimal – three killed and ten wounded – while the raiders lost about 100 dead and wounded out of a total of some 1,000 men. Twice the ascari had shown solid discipline while facing a larger force, and had emerged victorious. The inferior weaponry and fire discipline of the Mahdists played a large part in these defeats.

Major-General Oreste Baratieri took over as military commander of Italian forces in Africa on 1 November 1891, and also became civil governor of the colony on 22 February 1892. Baratieri had fought under Garibaldi during the wars of Italian unification, and was one of the most respected Italian generals of his time. He instituted a series of civil and military reforms to make the colony more efficient and its garrison effective. The latter was established by royal decree on 11 December 1892. The Italian troops included a battalion of Cacciatori (light infantry), a section of artillery artificers, a medical section, and a section of engineers. The main force was to be four native infantry battalions, two squadrons of native cavalry, and two mountain batteries. There were also mixed Italian/native contingents that included one company each of gunners, engineers and commissariat. This made a grand total of 6,561 men, of whom 2,115 were Italians. Facing the Mahdists, and with tension increasing with the Ethiopians, this garrison was soon strengthened by the addition of seven battalions, three of which were Italian volunteers (forming new 1st, 2nd and 3rd Inf Bns) and four of local ascari, plus another native battery. A Native Mobile Militia of 1,500 was also recruited, the best of them being encouraged to join the regular units. Like all the other colonial powers, the Italians also made widespread use of native irregulars recruited and led by local chiefs.

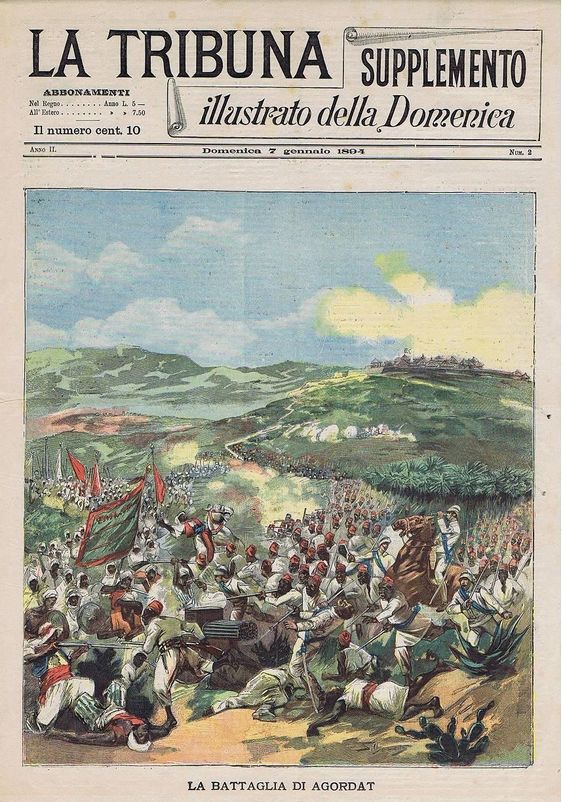

The first big test came at the second battle of Agordat on 21 December 1893. A force of about 12,000 Mahdists, including some 600 elite Baqqara cavalry, headed south out of the Sudan towards Agordat and the Italian colony. Facing them were 42 Italian officers and 23 Italian other ranks, 2,106 ascari, and eight mountain guns. The Italian force anchored itself on either side of the fort at Agordat, and from this strong position they repelled a mass attack, though not without significant losses – four Italians and 104 ascari killed, three Italians and 121 ascari wounded. The Mahdists lost about 2,000 killed and wounded, and 180 captured.

When the Mahdists launched raids across the border in the spring of 1894, the Italians decided to take the offensive and capture Kassala, an important Mahdist town. General Baratieri led 56 Italian officers and 41 Italian other ranks, along with 2,526 ascari and two mountain guns. At Kassala on 17 July they clashed with about 2,000 Mahdist infantry and 600 Baqqara cavalry. The Italians formed two squares, which inflicted heavy losses on the mass attacks by the Mahdists, before an Italian counterattack ended the battle. The Italians suffered an officer and 27 men killed, and two native NCOs and 39 men wounded; Mahdist casualties numbered 1,400 dead and wounded – a majority of their force. The Italians also captured 52 flags, some 600 rifles, 50 pistols, two cannons, 59 horses, and 175 cattle. This crushing defeat stopped Mahdist incursions for more than a year, and earned Baratieri acclaim at home. (In 1896 the Mahdi’s followers would make several more incursions into Eritrean territory, but without success. Fighting the Italians seriously weakened the Mahdiyya, and contributed to its defeat at the hands of Kitchener’s Anglo-Egyptian army at Omdurman in 1898.)

Colonial Italy

Italy entered the Horn of Africa through a window of commercial opportunity. Following the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869, an Italian steamship company, Rubattino, leased the Port of Assab on the Red Sea from the Sultan of Raheita as a refueling station. During the next year, Rubattino purchased the port for $9,440 (a bargain for such a hot property). Rubattino hoped to make money by controlling the traffic in slavery and arms smuggling.

Meanwhile, in Europe, the parliament of the newly united Kingdom of Italy met in Rome for the first time in November 1871. The new government was ambitious and sought ways to prove its bona fides in the eyes of the world. Colonization of lands unclaimed by other European powers was viewed as one path to national prestige. Although Italy coveted African lands across the Mediterranean, it failed in attempts to occupy Tunisia and Egypt in 1881-1882. Considerations of prestige were thought to demand expansion somewhere, and imperialists of the time proclaimed that the “key to the Mediterranean was in the Red Sea” (where incidentally, there would be less chance of Italy’s clashing with other European interests). Thus, in 1882, the Italian government bought Assab from Rubattino for $43,200, thereby providing the steamship company a handsome profit on its investment and unofficially establishing the first Italian colony in Africa since the days of the Caesars.

Emboldened by its real estate acquisition on the Red Sea, Italy participated in the Conference of Berlin in 1884- 1885 that “divided up” what was left of Africa after the initial wave of European colonialism. At the conference, Italy was “awarded” Ethiopia, and all that remained was for her troops to occupy the prize. This would take time, and cautious expansion from Assab.

To ensure the safety of its new port, Italy moved to the surrounding interior. From its Assab base the Italians, through the good office of Britain, occupied the nearby Red Sea port of Massawa (replacing the Khedive of Egypt, who had decided he could no longer keep a garrison there) and adjoining lands in 1885. At that time, the Ethiopian emperor, Yohannes, was distracted by wars in the highlands and against Sudanese Mahdists who were also battling the British in the Sudan. After the Mahdi defeated General Charles “Chinese” Gordon at Khartoum in 1885, the Italians were left as the only Europeans in what they perceived as a hostile land. The Italian government felt compelled to increase the military support of its commercial stations.

Emboldened by their easy occupation of the coastal areas, the Italian army and local conscripts invaded the highlands in the late 1880s. Italian government leaders probably overestimated the possible gains in commerce and prestige from this move. The reputation of Ethiopians as spirited fighters, evidenced in battle against the Egyptians in the 1870s and against the Mahdists in the 1880s, apparently was not taken seriously by the Italians. That attitude soon changed when Ethiopian mettle was tested in the rough terrain of Tigray. After the Italians provoked some “incidents” on the frontier, their soldiers encountered an Ethiopian force of 10,000 led by Ras Alula Engeda, Emperor Yohannes’s governor of the Mereb-Melash, the territory north of the Mereb River and stretching to the Red Sea – in other words, the land the Italians were occupying. At Dogali, some 500 Italians were trapped and massacred in battle by Alula’s men.

Their pride wounded, the Italian government moved aggressively in retaliation. Parliament voted 332 to 40 to increase military appropriations, raised a force of 5,000 men to reinforce existing troops, and attempted to blockade Ethiopia.

To ease his “Italian problem,” Emperor Yohannes sought the diplomatic help of Great Britain. As part of the peace diplomacy, Yohannes agreed to give compensation to the Italians for Dogali and to use Massawa as a trading post. By this time the French had started building a railroad from Addis Ababa to Djibouti. This would give Ethiopia a trading outlet on the Red Sea outside Italian influence. Italian leaders, nursing a sense of shame and a thirst for revenge, decided something had to be done.

The man to do it was Francesco Crispi, the prominent leader of the democratic or radical left wing of the Italian government and the most striking political personality produced by the new Italy. Eloquent, forcible, and dominating in Parliament, the Sicilian Crispi served as Prime Minister from 1887-1891 and again from 1893-1896. A super-patriot, Crispi longed to see his country, that he always called “my Italy,” strong and flourishing. He envisioned Italy as a great colonial empire, and Crispi’s impulsive hubris would play a vital role in shaping the events that would unfold in the region. Following the debacle at Dogali, Crispi told German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck that “duty” would compel him to revenge. “We cannot stay inactive when the name of Italy is besmirched,” Crispi asserted. Bismarck is purported to have replied that Italy had a large appetite but poor teeth.

With their military momentum stalled and the bluster of their milites gloriosi punctured, the Italians, led by Crispi, resorted to guile and diplomacy to promote their expansionist aims. Taking a page from the British book of colonial domination, the Italians pursued a policy of divide and conquer. They provided arms to Ras Mengesha of Tigray and all other chiefs who were hostile to the Emperor. During his internecine rivalry with Yohannes, even the Negus of Showa, Menelik, sought closer collaboration with the Italians. Menelik allegedly welcomed the Italians as allies in a common Christian front against the Mahdists.

When the Emperor Yohannes was killed in battle against the Mahdists at Metemma in March 1889, the Italians sensed an opportune moment to solidify their foothold in the country through negotiation. Count Pietro Antonelli headed a mission to pay homage to the new Emperor, Menelik II, and to negotiate a treaty with him. The Treaty of Wuchalé (Uccialli, in Italian), signed in Italian and Amharic versions in May 1889, ultimately was to provide the raison d’etre for the Battle of Adwa.

Under the treaty, the Italians were given title to considerable real estate in the north in exchange for a loan to Ethiopia of $800,000, half of which was to be in arms and ammunition. The piece de resistance for the Italians, however, was Article XVII, which according to the Italian version bound Menelik to make all foreign contacts through the agency of Italy. The Amharic version made such service by the Italians optional.

Proudly displaying the Roman rendition of the treaty in Europe, the Italians proclaimed Ethiopia to be her protectorate. Crispi ordered the occupation of Asmara, and in January 1890 he announced the existence of Italy’s first official colony, “Eritrea.” To bolster Italy’s colonial policy, on April 15, 1892, Great Britain recognized the whole of Ethiopia as a sphere of Italian interest. Italian Prime Minister Giovanni Giolitti (whose eighteen-month premiership interrupted Crispi’s tenure in the office) affirmed that “Ethiopia would remain within the orbit of Italian influence and that an external protectorate would be maintained over Menelik.” The Ethiopians were not too concerned with such Italian braggadocio until 1893, when Menelik denounced the Wuchalé treaty and all foreign claims to his dominions and attempted to make treaties with Russia, Germany, and Turkey. In a display of integrity rare among belligerent nations, Menelik paid back the loan incurred under the treaty with three times the stipulated interest. He kept the military equipment, however, and sought to rally the nation against a foreign invader.

The Italians railed at this insubordination by a “Black African barbarian chieftain,” and prepared to go to war to teach the Ethiopians a lesson in obedience. Having claimed a protectorate, Italy could not back down without losing face. Crispi, under fire at home from both conservatives and the extreme left bloc of Parliament for his “megalomania,” may have seen victory in Africa as his last chance for political success. From his perspective, a colonial war would be good for Italy’s (and his) prestige, and Crispi envisioned a protectorate over all of Ethiopia. General Antonio Baldissera, the military commander at Massawa, had a more modest goal – the permanent occupation of Tigray. The Italian Deputies would have been content with a peaceful commercial colony. With such occluded aims, the African campaign suffered generally from a lack of will among Italians in the homeland.

While the Italians massed arms and men in their Colonia Eritrea, their agents sought to subvert Ethiopian Rases and other regional leaders against the Emperor. What the Italians did not realize was that they were entering into the Ethiopian national pastime: the tradition of personal advancement through intrigue. Menelik, master of the sport, trumped the Italians’ efforts by persuading the provincial rulers that the outsiders’ threat was of such serious nature that they had to combine against it and not seek to exploit it to their own ends. The Emperor called his countrymen’s attention to the fate of other African nations that had fallen under the yoke of colonialism. The magic of Menelik worked. Whatever seeds of discord the Italians had planted sprouted as shoots of accord on the other side.

Meanwhile, Italy carried out further intrusions into Ethiopia. On December 20, 1893, Italian forces drove 10,000 Mahdists from Agordat in the first decisive victory ever won by Europeans over the Sudanese revolutionaries and “the first victory of any kind yet won by an army of the Kingdom of Italy against anybody.” Flushed with success on the battlefield, the Italian populace embraced new national heroes, the Bersagliere, soldiers of the crack corps of the Italian army. The Bersagliere, depicted in the press wearing “a pith helmet adorned with black plumes, facing a savage enemy on an exotic terrain,” appealed to the passionate patriotism of the masses and to the romantic adventurism of young men. Enthusiastic conscripts responded to the call to the colors.

The belligerent Italians soon mounted the strongest colonial expeditionary force that Africa had known up to that time. The Governor of Eritrea, General Oreste Baratieri, had about 30,000 Italian troops and 15,000 native Askaris under his command (Great Britain would surpass that number a few years later when 250,000 troops would be sent to South Africa during the Boer War). Secure in his new military strength, Baratieri again went after the Mahdists. On July 12, 1894, his forces drove the Dervishes from Kassala, killing 2,600 while losing only 28 Italian dead – the most one-sided victory won by Europeans over the Mahdists.

The Italians were not doing so well on the diplomatic front, however. In July 1894, Russia had denounced the Treaty of Wuchalé. An Ethiopian mission was received in St. Petersburg “with honors more lavish than those accorded any previous foreign visitors in Russian history.” To add injury to diplomatic insult, Tsar Nicholas sent Ethiopia more rifles and ammunition.

In 1895, Baratieri followed up his victory over the Dervishes with another successful offence at Debre Aila against an Ethiopian force larger than his own, under the command of Ras Mengesha. The Italians drove out the ruler of Tigray and prepared for a permanent occupation of his land. Other minor military actions of the Italians in 1895 fuelled the anger of the Ethiopian masses and leaders alike, who viewed the invasion as a threat to their nation’s sovereignty.

Emperor Menelik’s reforms had transformed the economy and improved the tax base of the country enabling him, as never before, to raise and equip armies. In the highlands, Menelik massed his troops and marched north to meet the Italian aggressors. In December, an Ethiopian army of 30,000 trapped 2,450 Italian troops at Amba Alaghe, the southernmost point of Italian penetration. In the ensuing battle, 1,320 Italians were killed or taken prisoner. At the same time, Ethiopians laid seize to a formidable Italian fort at Mekele. Menelik, perhaps still hoping to settle his conflict with the Italians peacefully, negotiated a settlement whereby the besieged were evacuated and allowed to join their compatriots.

These events infuriated Crispi, who taunted his commanders for their incapacity and cowardice. He called the Ethiopians “rebels” who somehow owed allegiance to Italy. Although the opposition in parliament led by Giolitti criticized the government for providing inadequate food, clothing, medical supplies, and arms to the troops, Crispi was able to garner additional military appropriations by claiming that the troop movements were purely defensive. He assured parliament that the war in Ethiopia would be a profitable investment.