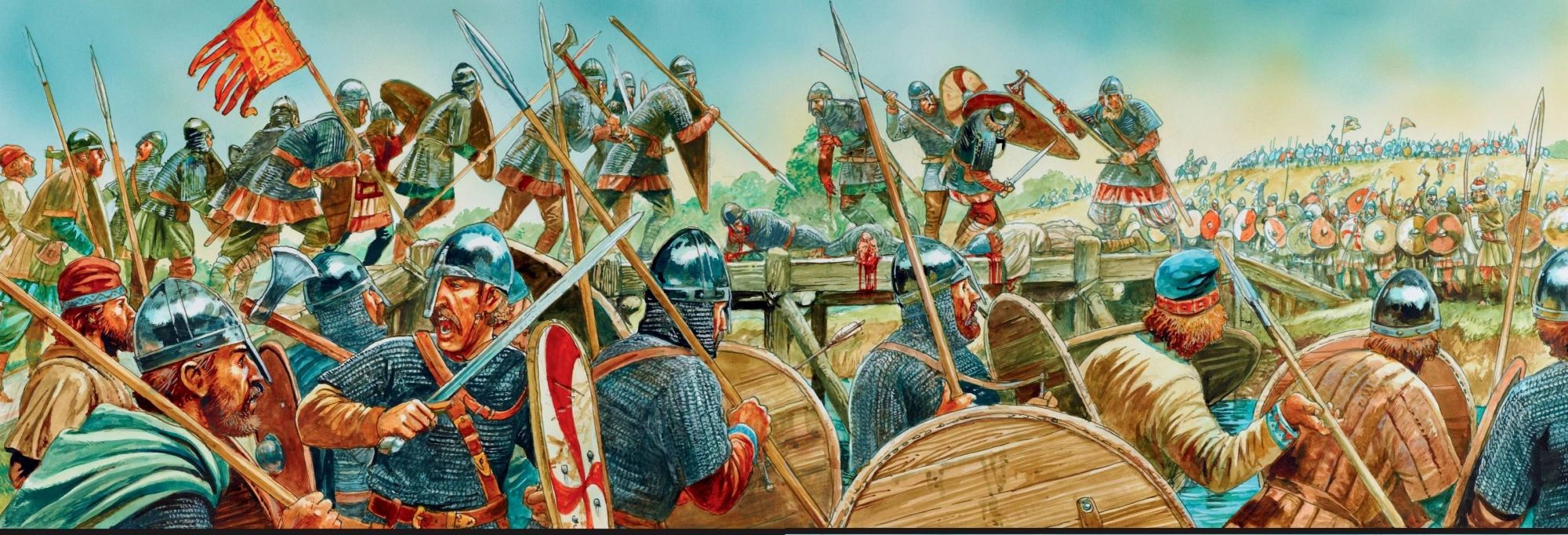

Battle of Stamford Bridge, 1066. The English army under King Harold Godwinson fights off an invading Norwegian force led by King Harald Hardrada.

On Edmund’s death in 946, he was succeeded by another brother Eadred (946–56), who in the first year of his reign conquered Northumbria and was granted oaths by the Scots ‘that they would do all that he wanted’. More oaths then, but no details. At Tanshelf, in 947 Archbishop Wulfstan of York and the councillors of the Northumbrians are said to have pledged themselves to the king, but ‘within a short while they belied both pledge and oaths also’. The reason for this recalcitrance lay in the arrival of a famous Viking leader, one Eric Bloodaxe whose control of the Viking kingdom of York quickly became legendary. Eric, who held Northumbria from an apparent promise made by Athelstan, was eventually defeated, murdered by one of his own men after the grim campaigning of Eadred in the area.

The brief reign of Edwy, king in Wessex (955–9) records no hostage exchanges, but plenty of domestic politicking. Edwy’s grip on power subsided as his brother the young Edgar (959–75) gained acceptance in both Mercia and Northumbria and eventually Wessex itself. Edgar’s reign over England was one of peace bought by the threat to any enemy of overwhelming military force. A huge and energetic navy and a vast land army were enough for Edgar to concentrate on matters such as monastic reform and other political issues. In an act of overwhelming symbolism the king took an army to Chester. Here, at the edge of the old Roman world, King Edgar symbolically took the helm of a rowing vessel and was rowed by up to eight subservient leaders on a boat along the River Dee to the monastery of St John the Baptist. Oaths were sworn, and the promise from all these rulers was that they would be faithful to the king of the English and support him both on land and at sea. These men were Malcolm, king of the Cumbrians; Kenneth, king of the Scots; Maccus, king of ‘Many Islands’; Dunfal (Dunmail), king of Strathclyde; Siferth; Jacob (Iago of Gwynedd); Huwal (Jacob’s nephew and enemy); and one Juchil. Edgar’s passing remark after this event would ring in the ears of regional kings for centuries. Any of his successors, he said, could pride himself on being king of the English having such subservience beneath him.

On Edgar’s death in 975, Anglo-Saxon England was at its peak of power and influence. He was succeeded by his son Edward (975–9) whose reign leaves no record of hostage giving or oath taking. However, after Edward’s infamous murder at Corfe Castle and the rise to power of his half brother Æthelred II (979–1016) we enter a period of history whereby the role of the hostage once again leaps out from the pages of the chronicles and histories.

Æthelred’s reign was a little over eighteen months old when the Scandinavian raiders returned to England. Southampton was targeted first and we are told that many of the inhabitants were killed or taken prisoner. We are not told of the fate of these hostages, however. Nor are we told what happened to the people of Thanet in Kent and the region of Cheshire who also suffered similar fates. Soon, in 991, the Battle of Maldon would be played out in Essex between the local ealdorman Byrhtnoth and an invading Viking force. Here again, there is a mention of a hostage, but he is this time a Northumbrian hostage in the East Saxon Army. Pointedly, he is mentioned as having a bow, not a sword as one might expect. It is possibly an interesting glimpse into the equipment allowed for hostages when asked to participate in their captors’ campaigns.

Hostages were once again exchanged in 994 when the legendary Olaf Tryggvason and Swein of Denmark unsuccessfully attacked London. The chronicler Æthelweard, who, as we have observed, was a nobleman himself, played his own part in this negotiation as he and the Bishop of Winchester arranged for hostages to be sent to the Danish ships and for Olaf to be brought to King Æthelred for a baptism perhaps in the style of that which had happened to Guthrum all those years ago. Olaf’s interests would soon turn to Norwegian matters, but it remains the case that after this agreement with Æthelred, he never returned to England.

The later part of Æthelred’s reign saw the usage of hostages become widespread. Nothing, however, would quite match the drama of the fate of one man in particular whose fame throughout the northern Medieval world was eclipsed only by that of Thomas à Becket 150 years later. The Danish assault on Canterbury in September 1011 marked a notorious episode in the king’s reign. The Danes, when they entered the city, are supposed to have gone wild. Their rampage resulted in the capture of Ælfhere, the Archbishop of Canterbury and one Ælfweard, a king’s reeve, among others. Christchurch was plundered and countless people murdered in a long-remembered orgy of destruction.

The Danes stayed the winter in Canterbury. They suffered from illnesses brought about by the apparent unsanitary water supplies, but this much divine intervention was not enough to rid the English of their tormentors. It was, however, their key hostage whose fate attracted the attention of chroniclers. Not content with the silver offered to them to leave, they asked also for a ransom for the return of the archbishop. Ælfhere would have none of it. For his intransigence the pious archbishop was murdered at the hands of his captors in Greenwich. In a drunken frenzy, here at the termination of the Rouen to London wine trade route, one Dane pulverised the head of the archbishop with the butt end of his axe while the others hurled cattle skulls and bones at him on the hustings. The hideous event was carried out against the wishes of an observing Dane called Thorkell the Tall and it was an event that marked the beginning of a significant switch in Thorkell’s allegiance from the side of the Dane to that of the English king himself.

From the story of one famous hostage, we go to the handing over of countless people to the Danish King Swein in 1013. Swein, who had long harboured a bitter resentment against Æthelred, had sailed down the Humber and Trent to Gainsborough and called to him the men of Lindsey, those of the Danish Five Boroughs of the Danelaw (Nottingham, Stamford, Leicester, Lincoln and Derby) and Earl Uhtred of Northumbria. Their allegiance was cemented by supplies of hostages from ‘every shire’–a figure that must have been considerable. Some time after the hostages were given, Swein entrusted them to his son Cnut. It was a move that would have profound ramifications. Swein poured his forces south across Watling Street and fell upon Oxford, the townsfolk of which provided further hostages to him. Next, it was Winchester’s turn and in an embarrassing exchange for the English king, the Oxford story repeated itself. The beleaguered Æthelred and his new ally Thorkell remained in London, contemplating. It would not be long before the king would sail to Normandy, to the home of his wife Emma and into exile.

In February 1014 Swein unexpectedly died. He was succeeded as nominal king in England by his son Cnut. However, many Englishmen appealed to the exiled Æthelred to return to England and rule once again as their natural lord, although there would be conditions in the bargain. Æthelred did indeed return and not long after this he conducted a punitive campaign of destruction in Lindsey against the land of Cnut’s supporters. Cnut then decided to sail down the east coast of England to Sandwich where he dropped off those English hostages his father had passed to him, each with their hands, ears and noses cut off before they were put to shore. Then, after this grisly act, the would-be Danish king of England set sail for Denmark.

Cnut did, of course, return to England. Through the political machinations of one famously seditious Eadric Streona, a turncoat English earl, he secured a hold on power. But in an unlikely turnaround Edmund Ironside, the son of Æthelred, found himself with the support of the Danelaw (through marriage) ranged against Cnut and Eadric based in the south of England, the traditional strong areas for the family of Edmund. With a reluctant King Æthelred lying ill in London, there began a giant circle of campaigning across the country which also involved Uhtred of Northumbria, whose grisly end we have already observed. Soon Æthelred would die in London and there began a siege and subsequent campaigns in Wessex between Cnut and Edmund which eventually ended in a pyrrhic victory for the Dane.

The situation in London, if the chronicler Thietmar of Merseburg is to be believed, was full of dramatic bargaining. Emma of Normandy, Æthelred’s widow, was to hand over her sons ‘Ethmund’ (Edward) and ‘Athelstan’ (Alfred). These were her sons and heirs to the English throne, but they are both said to have escaped in a boat. A tangled tale then ensued involving the mutilation of a great many English hostages. We shall never know the truth about the fate of the hostages or their exact numbers. Thietmar has his critics when it comes to his accounts of these important events in London.

Further sieges at London and pitched battles in the countryside around Wessex between Edmund and Cnut followed this episode. Eadric Streona subsequently changed sides and when supporting Edmund bitterly betrayed him on the battlefield at Ashingdon. The agreement finally reached between Edmund and Cnut, at an island in the River Severn after they had fought each other to a standstill up to this point, saw the English king hold Wessex and the Dane hold the rest of the country including London. Once again, the agreement was sealed with hostages. There is also a hint in the sources that Edmund offered single combat to Cnut, but nothing is really known of it.

On 30 November 1016 Edmund Ironside died. The finger of suspicion surrounding his death was historically pointed at Eadric Streona, but no absolute proof has ever been offered. Cnut in an instant took the throne of the whole of England. Throughout his reign he ruthlessly dispatched his political enemies and always seemed to be aware of the potential of the popular appeal of the line of Cerdic, Æthelred’s ancient royal family. Political assassinations meant that his grip on power became stronger and there is no evidence of any significant hostage exchanges for many years. But in 1036, after Cnut died, there was one hostage whose fate was every bit as significant as that of Archbishop Ælfhere a quarter of a century earlier. Earl Godwin, a favourite English magnate of Cnut’s, whose new allegiance was very much in the camp of the new King Harold Harefoot (1036–40), was the main player in the drama of the murder of Alfred, son of Æthelred.

For the Normans, the death of Alfred would pretty much justify the entire Norman Conquest. Alfred, half Norman himself, was on his way to meet his mother Emma. Having landed at Dover and tracked his way towards Winchester, Alfred and his followers arrived at Guildford where they were met by Godwin and his men. Alfred was carried away and taken hostage to Ely where he was brutally blinded. The others were either killed or sold into slavery. It was a horrible affair. Although the Norman chroniclers never forgave Godwin for his role in the taking of Alfred, Godwin would later atone for it when Harthacnut (1040–2)–Alfred’s kinsman–came to power. As king of England, Harthacnut made Godwin stand trial for the crime and received from the powerful earl a magnificent ship complete with its warrior complement for his compensation.

The early years of Edward the Confessor’s reign (1042–66) saw no significant usage of hostages as such until 1046, when Earl Swein, the eldest son of Earl Godwin and whose new earldom bordered southern Wales, went into that country in force. He allied himself with Gruffydd ap Llewelyn, king of Gwynedd and Powys, and was granted hostages by his southern Welsh enemies. Their fate is unrecorded. The Godwin family would, however, continue to dominate the politics of King Edward’s reign, but it was with the old man Godwin that things would come to a head between king and earl and once again hostages would play their part.

There followed royal appointments of Normans, the building of castles in Herefordshire and Dover and one infamous visit to England by Eustace of Boulogne, whose men ran amok in the streets of Dover. These were just some of the reasons for the tensions between Godwin and King Edward. By 1051 Godwin had had enough of it all. He had raised a huge army from his own Wessex combined with Earl Swein’s men from Oxfordshire, Herefordshire, Somerset and Berkshire and Earl Harold’s men (the future king) from East Anglia, Essex, Huntingdon and Cambridgeshire. At Tetbury, just 15 miles away from a concerned King Edward, this force came together. A demand was sent to the king by the earl. There will be war unless the king gave him Eustace of Boulogne and the men ‘who were in the castle’, a reference possibly alluding to either the castellans of Dover or the notorious Herefordshire Normans. But against Godwin would be ranged the forces of Earl Siward of Northumbria and Earl Leofric of Mercia, plus a contingent of knights from Earl Ralph the local Norman. Once these forces had been gathered after urgent messages were sent to the north there was something of a stand-off. It seemed to those present that a battle between the finest men of England in a time of foreign interest in the English throne would be of such grave consequence that it should not be allowed to go ahead. The situation was therefore resolved with the exchange of hostages and the arrangement that there would be another meeting on 24 September between the protagonists in London.

Godwin fell back to Wessex in the meantime and the worried king took the time he had bought to raise a huge army from Earls Leofric and Siward’s lands and bring them to London for the meeting. This took around two weeks. At London the net was closing in on Godwin and his family. Godwin asked for safe passage when he was at Southwark, but this time the hostages were refused him. The upshot of the meeting was that he was outlawed along with Swein and Harold. They had to leave England. Before they did this however, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records that the thegns of Harold were ‘bound over’ to the king, indicating that a shift in lordship bonds of Harold’s followers was part of the punishment. So, as a ship was prepared at Chichester Harbour the Godwin family sailed off to the court of Baldwin of Flanders, all except Harold who sailed via Bristol to Ireland. At this time it is thought that Wulfnoth, Harold’s brother, and Hakon, Earl Swein’s son, were given to the king as hostages. The way was clear for a young man from Normandy–Duke William–who had been promised the throne of England to pay a visit to Edward’s kingdom.

Godwin was no fool. On 22 June 1052 he left the Yser Estuary with a small fleet and evading Edward’s forty ships at Sandwich, he landed on the Kentish coast. His former men in Kent came to him as did the ship men of Hastings and the men of Sussex and Surrey who declared they would ‘live and die with him’. The earl’s son Harold joined forces with him and between them they gathered a force large enough to intimidate the king on his own doorstep in London. Godwin had made the most triumphant of returns. In the subsequent scramble for safety, the Norman Archbishop of Canterbury Robert of Jumièges may well have taken Wulfnoth and Hakon to Normandy as he and others fled the vengeful Godwin family, handing the hostages over to Duke William.

Godwin’s subsequent death in 1053 and the rise of his son Earl Harold set the scene for the years preceding the Conquest. Harold’s hostage-taking successes on his remarkable Welsh campaigns. Harold Godwinson’s contribution to the story of oath making, however, is legendary–if a little controversial. His journey to France in 1064 saw him unexpectedly fetch-up on the shores of Count Guy’s Ponthieu. The count could not believe his luck. It seems that Harold was on his way to William of Normandy presumably with King Edward’s promise of the English throne. However, Guy’s subsequent imprisonment of Harold before he reluctantly handed him over to William amounts to a very high-profile hostage taking. Guy almost certainly was holding out for a ransom as he presumably believed that as master of these dangerous lee shores he had such a right. But William would have none of it and took the English earl on a Breton campaign with him, holding him at court and making him his man. During this period the famous oath was extracted at Bonneville from Harold on ancient relics–a scene depicted in the Bayeux Tapestry–that Harold would support Duke William’s claim to the English throne. However, we should not forget that the kinsmen of Harold were hostages in the Norman court and the riches that Harold had taken with him on his ship may well have been to entice Wulfnoth and Hakon’s captor into releasing them, another possible motive behind the journey. Nor should we miss the contemporary historian William of Poitiers’ account that the oath swearing was not in fact as one sided as history has subsequently portrayed it. Harold had asked William that he recognise all of Harold’s land holdings in the event of the death of King Edward. We will never know what was really said or done in Bonneville that year, but the sources speak of a proposed marriage of Harold’s sister to a Norman noble and of Harold taking Agatha, William’s daughter for a bride. It is suggested by the Medieval historian Eadmer that William would allow Harold to return to England with Hakon and would release Wulfnoth once Harold had masterminded the succession of William to the throne. In the event, Harold did indeed return with Hakon, leaving Wulfnoth behind.

Harold’s subsequent elevation to the throne, his brother Tostig’s banishment and alliance with Harald Sigurdsson of Norway are the stuff of history. It all led to the invasion of Northumbria by Harald and Tostig and the opening battles of the tumultuous year of 1066. After Harald and Tostig’s victory over Earls Edwin and Morcar at Fulford Gate outside York on 20 September 1066, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records that York gave hostages to the two victors, with the chronicler John of Worcester noting that 150 were exchanged on either side. If this is the case, it would seem Harald Sigurdsson, despite his victory, was in a mood to do business with Northumbria in his quest for the English throne. The need for further hostages was to be satisfied by a rendezvous at the junction of roads to the east of York. History would show that here at Stamford Bridge on the crossing of the Derwent the English King Harold and his men would be ahead of the allies and achieve a famous victory, but once again the issue of the hostage exchange plays centrally in the story. After the crushing and total defeat of the Norwegians at the hands of the English, the remnants who were allowed to sail away by King Harold included Earl Paul of Orkney, who dutifully left hostages behind promising, along with the son of the Norwegian king, never to return.

William the Conqueror’s usage of the hostage was no less effective. After the victory at Hastings, he extracted hostages from the remaining English nobility at Berkhamstead during a punitive campaign conducted around southern England. The submission of Edgar the Ætheling (with whom William would have a curiously long and troubled relationship) and the notable Londoners with him did not stop the countryside from being pillaged and burnt. A new era was dawning as England began to feel the effects of the Norman style of strategic warfare.

It can be seen that the history of Anglo-Saxon warfare is very well evidenced by an account of one of its chief mechanics–that of the hostage negotiation. Deals were broken, oaths sometimes meant nothing, treaties ignored. On other occasions, the method worked very well indeed. But always somewhere in the thick of it stood a hostage. Blinded, mutilated, incarcerated or sometimes just kept at court and treated well enough, the story of the hostage is the story of Anglo-Saxon warfare. We have observed many examples of the grim fate of hostages throughout the period. One is drawn to sympathise finally with a certain Æthelwine, nephew of Earl Leofric, whose mention in Hemming’s Cartulary (a list of charters and documents compiled around the time of the Norman Conquest) includes the fact that he had lost both hands while a hostage of the Danes. If our Æthelwine could ever have dictated his story, it would not have made pleasant reading for anyone.