The American navy played no part in the campaigns. The war created the navy, but it could not call into being a force of great power. The financial resources for a strong navy simply did not exist; nor for that matter did the conviction that a navy equal to Britain’s was needed.

The war at sea commenced before there was an American navy, with the first actions occurring within a few weeks of the battles at Lexington and Concord. Perhaps the earliest—in June—involved the citizens of Machias, a small port in Maine some 300 miles northeast of Boston. These Maine patriots captured his majesty’s schooner Margaretta, commanded by a young midshipman who had threatened to fire on the town if its liberty pole was not cut down. The midshipman reconsidered this threat shortly after making it, but too late to persuade the people of Machias not to respond. In an armed attack a group captured the Margaretta and two sloops which had accompanied her. The midshipman died in the defense of his command.

Most of the actions of sea-going patriots in the first year of the war were not against vessels of the Royal Navy. Almost all of his majesty’s ships were too heavily armed and too well sailed for the Americans to attack. The skippers of privateers from small Massachusetts ports preferred to engage transports and merchantmen carrying munitions and supplies to the British army in Boston. They did so to good effect—in all they brought in fifty-five prizes in the first year of the war.

George Washington commissioned many of the privateers making these captures. Washington’s awareness of the importance of the sea to the land campaigns in America probably surpassed that of any of the British commanders he faced in the war. But for much of the war his strategic ideas about the use of the sea could not really affect operations, for he had no fleet. Until the French entered the war, there was no possibility that he would ever obtain one.

He could use what was available, however. There was an abundance of inlets and ports along the American coast and there was a large supply of small vessels—brigs, sloops, and schooners—as well as of shipwrights and sailors. On the eve of the Revolution, American shipyards built at least a third of the merchant ships sailing under the Union Jack. American forests yielded oak for hulls and decks and pine for masts. Sails and rope were also made in America.

The most immediate way to use the sea was to strike at British merchant ships, not only to disrupt the supply of the army under siege in Boston but also to add to the meager supply of American weapons and munitions. The first ship Washington sent into Continental service, the Hannah, a seventy-eight-ton schooner, failed in both missions. Nicholson Broughton, a Marblehead shipper, took command of the Hannah when she entered the service in August 1775. Broughton soon displayed a propensity for capturing ships owned by Americans and calling them the enemy’s. This inclination led him to make a voyage to Nova Scotia with Captain John Selman, a man of similar tendencies. These two seadogs plundered Charlottetown, a small village, and kidnapped several leading citizens whom they proudly brought to Washington’s headquarters in Cambridge. Washington, embarrassed by this behavior, released the prisoners and quietly let his sea captains’ commissions expire at the end of December

Broughton and Selman were not alone in seizing the main chance. Many American skippers used any pretext to take the ships of friendly merchants. They also captured British ships which were privately employed and not engaged in supplying the army in Boston.

More captains acted in the Continental interest. One, John Manley of the Lee, made a capture in late November which delighted Washington and the Americans besieging Boston. Manley ran down the Nancy, an ordnance brig of 250 tons, bound for Boston with 2000 muskets fitted with bayonets, scabbards, ramrods, thirty-one tons of musket shot, plus bags of flints, cartridge boxes, artillery stores, a thirteen-inch brass mortar and 300 shells. Not long afterward, Washington appointed Manley a commodore and gave him command of schooners charged with the responsibility of patrolling Massachusetts waters.

Disposing of prizes and cargoes before independence provided Washington and the privateersmen with a delicate problem. Since throughout 1775 and in early 1776 the possibility existed that the dispute with Britain might be settled short of independence, the question of how to sell the captures had to be faced. They could not be sold in the old vice admiralty courts. Could Americans in fact sell what they had seized without formal admiralty proceedings? Not that they expected the British to be understanding and sympathetic if the old rules were observed. They were going to take British property and hold prisoners for a time whether the two sides eventually reconciled or not. But who had jurisdiction over the captures? Was there a Continental responsibility or should they rely on provincial admiralty courts? Eventually the Massachusetts Provincial Congress came to their aid and established admiralty courts where systematic procedures for disposal of ships and cargoes were worked out.

Massachusetts acted in part because the Continental Congress, groping toward a naval policy just as it groped toward independence, had failed to respond swiftly. During the year that followed the opening of the war, Congress first seemed to suggest that the naval war should be the business of the states. And several states approved plans for fitting out armed vessels which were to attack British transports. By autumn 1775 a small-scale building program existed in several states; and Washington had six armed craft nosing about the waters off Boston. Congress itself in November ordered that four ships should be put into its service and began to frame a policy for the disposal of captures. At the end of the year it directed that thirteen frigates should be built for an American navy.

As far as Congress was concerned its vessels and those of the states should strike only those British vessels which had attacked American commerce or which were supplying the British army. Congress was not inclined to pass its own prohibitory act until it received news of Parliament’s. As it began the move toward declaring independence in 1776, it also moved toward a full-scale naval war.

Congress always appeared to believe that in a committee it possessed the most useful instrument for making war. Thus in November 1775 when it first ordered that merchant ships should be fitted out as armed cruisers, it assigned the task to a naval committee. As Congress’s ambitions and its building program expanded so also did its administrative committees. The naval committee sank in administrative waters early the next year, only to be replaced by a marine committee. Much of the actual work of establishing a fleet was done between 1777 and 1781 by a Navy Board of the Eastern Department. This board of three, from Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Rhode Island, did the rough work of getting ships and men together. Located in Boston, the board tried to stay out of Congress’s way while carrying out its orders. To a remarkable degree it succeeded in both operations. But Congress was not satisfied with regional efforts and certainly not with regional control; late in 1779 it created the Board of Admiralty to give overall direction to the navy.

Modeled on the British Admiralty Board, the American creation included non-congressional members as well as delegates from Congress. Throughout its short life two men, Francis Lewis, a merchant and former member of Congress from New York, and William Ellery, a delegate from Rhode Island, did most of its work. These two tried to add to the number of frigates which Congress had authorized and to persuade Congress to support the navy. Congress, however, had lost interest in the navy and found uses for public money elsewhere.

The navy shrank steadily. In the summer of 1780 Congress transferred control of what remained, a handful of frigates, to General Washington, intending that their actual control would be vested in Admiral Ternay, the French officer who had brought General Rochambeau and his army across the Atlantic to Newport earlier in the year. The next year the administration of these American vessels was removed completely from the admiralty board and vested with the superintendent of finance, Robert Morris. With this transfer any possibility that the navy might gain a powerful fleet vanished. Morris had more important problems to contend with, and he like most others saw little need for a navy in 1781.

This organizational history of the early navy explains the failure of American naval power in the Revolution. Aside from the achievements of the “cruising war,” Captain Alfred Thayer Mahan’s term for strikes of privateers, the American efforts on the ocean were paltry. The privateering, however, did make a difference by making the problem of supplying their army more difficult for the British and by capturing arms and stores which Washington’s army put to good use.

A part of the Continental navy—the regular navy—also raided commerce, and one commander did more—struck fear into the British in the home islands that their coastal towns and cities would be destroyed. The commander was John Paul Jones, a Scot with remarkable courage and daring.66

Jones was born John Paul at Arbigland in Kirkbean, a parish of the Lordship of Galloway—he added Jones after he came to America. Born in 1747, he left his birthplace when he was thirteen years old. In 1761 he was apprenticed to a merchant-shipowner of Whitehaven, an English port across the Solway. There he began his great career on the sea—as a ship’s boy on the Friendship, which over the next three years made her way back and forth between England and Virginia, usually with a stop in the West Indies, where rum and sugar were taken aboard, carried to Virginia, where tobacco and occasionally lumber and pig iron were picked up for the return to Whitehaven.

John Paul’s merchant-master went broke in 1764 and released his apprentice from service. Paul spent most of the next three years on slave ships. The slave trade was a brutal business, and Paul apparently left it with relief, obtaining his discharge in Kingston, Jamaica, and sailing for home in 1768 on a Scottish ship. On this voyage both master and mate died. No one on board, except John Paul, could navigate. He took over and brought her safely home.

Pleased by this demonstration of seamanship and command, the owner put Paul aboard another ship as master. He was only twenty-one years old, but he had none of the softness of youth. Outward bound in 1769, he had the ship’s carpenter, Mungo Maxwell, whipped with the cat-o’-ninetails. Maxwell left the ship after she arrived at Tobago and lodged a complaint against Paul. When the case was dismissed, the disappointed Maxwell, apparently in good health, sailed for home; but he took sick and died. When Paul returned home the sheriff arrested him on Maxwell’s father’s charge of murder. Paul did not completely clear himself until he returned to Tobago and was able to obtain a statement from the judge that the lash had not contributed to Mungo Maxwell’s death.

An incident in 1773 proved even more serious. Paul, in command of a merchant ship, arrived at Tobago only to be faced with a mutiny. He ran the ringleader through with his sword and then fled the ship and the island and headed for the North American mainland. By summer 1775 he was in Philadelphia, a city in rebellion but a place he found to be a good deal more hospitable than Tobago.

Joseph Hewes, a delegate to the Continental Congress from North Carolina, eased John Paul Jones’s way in Philadelphia. Jones, the name he added to conceal his identity, had met Hewes while on the run from Tobago. A sailor in search of a billet, preferably a command in the Continental navy, could choose no better friend than Joseph Hewes, chairman of the Marine Committee, which selected the officers for the Continental navy.

Jones wanted a command. He wanted to fight in the cause of the united colonies. He began to espouse the principles of liberty in these months—and he never really stopped. Early in December 1775 he received a commission as first lieutenant in the Continental navy assigned to the Alfred.

The Alfred saw considerable action in the next few months, and Jones performed well. In May 1776 he was given the sloop Providence to command, with a temporary rank of captain. He drove the Providence hard, took many prizes, fought the ship well when opportunity showed itself, and gradually began to impress Congress with his ability.

Congress proved its regard in June 1777, giving Jones command of the sloop of war Ranger and ordering him to France where he was expected to pick up another ship and to raid enemy commerce around the British Isles. Jones sailed later in the summer and anchored at Paimboeuf, the deep-water port of Nantes. It soon became clear that John Paul Jones did not fancy himself to be just another raider of British merchantmen. He aimed for bigger targets: He would raid British ports and tie up the Royal Navy. By April of the next year, with the Ranger refitted and now at Brest, he was ready. Sailing into the Irish Sea, he decided to strike Whitehaven, familiar ground to him and surrounded by familiar waters. Early on April 23 he entered the port and found it crowded with ships. He put ashore a small landing party and set afire a collier. The blaze failed to spread, and the town was soon aroused and excited. There was no way to deal effectively with the crowds that gathered and apparently little chance of doing more physical damage even though there was no armed opposition present.

Jones next took the Ranger across Solway Firth to St. Mary’s Isle—it was now mid-morning—with the intention of abducting the Earl of Selkirk. As things turned out, he was not at home, and the landing party carried off nothing more valuable than the family silver. But the next day the Ranger did capture something of importance—the sloop of war Drake, a well-armed vessel encountered off Belfast Lough. The Drake fought effectively for two hours—her captain died with a bullet in his brain, and her executive officer was seriously wounded—but the Ranger fought more effectively.

By May 8, Jones had the Ranger safely back at Brest. Her voyage, though it did no great damage either to British ports or commerce, had been a sensational success. The psychological damage—the blow she struck to British pride and spirit—was extensive, though there is no evidence that her raid produced a change in the deployment of royal warships. British newspapers gave the raid a great play with shouts of outrage—at Paul Jones—and grunts of scorn—at the navy’s inability to run him down.

The shouts soon after in Paris were in a lighter tone. The Ranger’s voyage had made Jones the lion of French society, the delight of the French government, and the ecstasy of French ladies. Jones got a larger ship, the Duras, to command, which he renamed the Bonhomme Richard in honor of Benjamin Franklin.

John Paul Jones could be patient, and he could be crafty, but he preferred to exercise other qualities. He was always an ambitious man. John Adams, who saw something of him at this time, said that he was “the most ambitious and intriguing officer in the American navy. Jones has Art, and Secrecy, and aspires very high.” Adams expected the unexpected from him. “Excentricities and Irregularities are to be expected from him—they are in his Character, they are visible in his Eyes. His Voice is soft and still and small, his Eye has keenness, and Wildness and Softness in it.” Adams saw, and heard, Jones in polite society—never aboard a ship in battle, which accounts for his impression that Jones spoke in a “soft and still and small” voice. But he was right about the eyes. They were sharp and could blaze with wildness, as the bust by Houdon and the portrait by Charles Willson Peale suggest. The eyes stared out from a strong face with a firm, prominent nose and a well-proportioned jaw. The eyes were important to a commander of rough and sometimes rebellious men, for Jones was not large, probably no taller than five feet, five inches, but he was lean and hard. The look of ferocity that he could throw out cowed weaker men.

This tough and resourceful commander sailed with seven vessels on August 14, 1779, from Groix Roadstead, intending to create as much havoc as possible in the British Isles. His ship, the Bonhomme Richard, was the largest ship—probably around 900 tons—he had commanded. She was getting old, and with all of her sails piled on, was still slow, but after he armed her she could throw out heavy fire in battle. She mounted 6 eighteen-pounders, 28 twelve-pounders (16 of them new models), and 6 nine-pounders. Of the remaining ships of his command, two were frigates, one was a corvette, one a cutter, and two were privateers. These last two took off on their own shortly after the squadron hit the open sea. Jones was not surprised; he had guessed that they would resist his orders in favor of free-lancing. Nor could he really depend on all the others for instant obedience to his orders. Their skippers were French and, perhaps, were a little jealous of their American commander. One, Pierre Landais, captain of the frigate Alliance, hated Jones. Landais has been described as being half-mad; on this voyage he was destined to behave as a full-fledged lunatic or as a traitor.

The squadron made its way at a leisurely pace to the southwest Irish coast and then turned north. On August 24, Landais came aboard the Richard and told Jones he intended to operate just as he pleased. Within the next few days the cutter Cerf disappeared. Jones had sent her off to find several small boats he had dispatched to reconnoiter the coast. The Cerf got lost and eventually made her way back to France.

Not everything went sour: the squadron captured prizes as it proceeded up the coast, and on September 3, just north of the Orkney Islands turned to the south. Off the Firth of Forth, on the east coast of Scotland, Jones decided to put a landing party ashore at Leith, Edinburgh’s seaport. His purpose was to threaten Leith with fire and collect a large ransom. The city fathers were terrified by the appearance of his ships, but a gale, which forced Jones’s ships out of the firth, saved them from having to buy him off. If nothing more had occurred, the cruise would have been reckoned a success. It had yielded prizes, it had produced fear in the home islands, and it had forced the British Admiralty to send ships of the Royal Navy in fruitless pursuit of John Paul Jones.

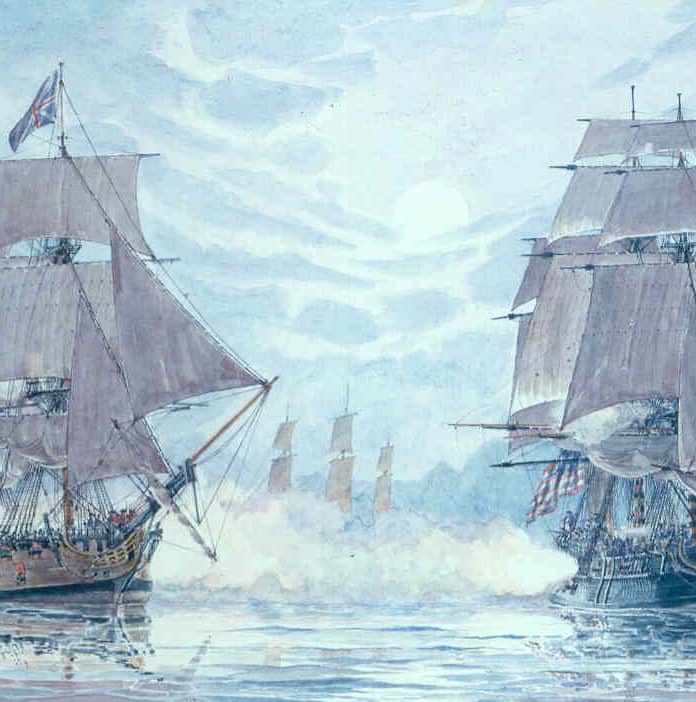

What happened next made everything else seem unimportant. On September 23, off Flamborough Head on the Yorkshire coast, the Bonhomme Richard fought one of the great battles in American naval history. At mid-afternoon of that day, the squadron sighted a large convoy escorted by the frigate Serapis (rated at 44 guns but carrying 50) and sloop of war Countess of Scarborough (20 guns). The Serapis, a new copper-bottomed frigate was commanded by Captain Richard Pearson, RN, a brave and competent officer.

Jones soon realized that he would have to defeat these escorts before he could attack the merchantmen. The wind was light, and it was sunset before he closed to firing range. The Alliance ignored Jones’s signal to “form line of battle,” as did the corvette Vengeance, a small lightly armed vessel. Frigate Pallas threatened to follow their example, sailing away rather than toward the enemy, but then put about and engaged the Countess of Scarborough. The Richard faced the Serapis, a more heavily armed ship, alone.

The battle opened with both ships on the same course, the Serapis off the Richard’s starboard bow. Early in the fight two of the Richard’s old eighteen-pounders burst with terrible effect on the crew serving them and on the entire heavy battery. This event convinced Jones that in order to win the battle, he would have to grapple with the Serapis and board her. The Bonhomme Richard was outgunned even before her eighteen-pounders exploded and, since it was unsafe to use the four that remained, could not win by trading salvos with her enemy. Had she been nimbler, Jones, a resourceful seaman, might have used her quickness to escape a heavy battering while punching the Serapis with the 28 twelve-pounders. But the Richard was anything but quick, and a heavy slugging match could only send her to the bottom. Captain Pearson, in contrast, attempted to maneuver in such a way as to bring his superior firepower to bear while keeping the Richard away.

Just after the eighteen-pounders burst, Jones tried to board Serapis on her starboard quarter. By skillful ship-handling he brought the Richard close, but the boarders were driven off by the English sailors. Pearson then tried to bring Serapis across the bow of the Richard, only to have Jones put his vessel’s bowsprit into the stern of the Serapis. It was apparently at this moment that Pearson called to Jones asking if he wanted to surrender, and received Jones’s magnificent reply, “I have not yet begun to fight.”

More intricate sailing followed by both ships with topsails backed and filled, vessels falling back, darting ahead (in the case of the Serapis), or lumbering in either direction (in the case of the Richard). At a crucial juncture, the Serapis ran her bowsprit into the Richard’s rigging and a fluke of her starboard anchor caught on the Richard’s starboard quarter. The two vessels were now locked together, starboard to starboard, with their guns pounding away. Below decks the advantage belonged to the Serapis; her batteries did terrible damage to the Richard. But on the open deck and in the topsails the Richard clearly had the upper hand. Jones’s French marines used their muskets to deadly effect, and the American sailors hanging above them poured fire and grenades down onto the Serapis. Before long only her dead remained above deck, and her crew serving the batteries below gradually gave way to the bullets and grenades that came from overhead, as the Americans worked their way onto the English topsails.

Several times, both ships caught fire and the shooting fell off as their crews attempted to put them out. Serapis took a frightful blow when William Hamilton, one of the bravest of the Richard’s sailors, dropped a grenade through one of her hatches into loose powder cartridges. The explosion that followed killed at least twenty men and wounded many others. This blast may have shattered Captain Pearson’s resolve; if it did not, the prospect of losing his mainmast shook him to the point of yielding. Jones had directed the fire of his nine-pounders against the mainmast—and had helped serve one of the guns himself.

It was now 10:30 P.M. The Richard was filling with water; her crew had suffered heavy losses; but her captain would not strike his flag, though several of his men begged him to give up. On the Serapis the condition of the crew was no better though the ship was in no danger of sinking. Pearson’s courage, however, trickled away with the blood of his men, and he himself tore down his ensign.

John Paul Jones had carried the fight to his enemy and had won through courage, spirit, and luck. Grappling with the Serapis had, in fact, been accidental though of course he had badly wanted to close with her. On the other hand, luck had also served the Serapis, for Captain Pierre Landais of the Alliance had decided to enter the fight early in the evening—against his own commander. The result was the delivery of three broadsides at close range into the Bonhomme Richard. Somehow Jones shook off these blows and everything that the Serapis could hit him with.

The casualties were dreadful on both sides—150 killed and wounded out of a crew of 322 on the Richard, and about 100 killed and 68 wounded out of 325 on the Serapis. Two days after the battle Jones abandoned the Richard. She was a gallant old vessel, but she could not be saved. Jones transferred his flag to the Serapis, and joined by the Pallas, which had taken the Countess of Scarborough, sailed for friendly waters.

Nothing in Jones’s career ever equaled his magnificent performance of September 23. He left Europe in December of the following year, leaving behind an admiring France and coming home to countrymen who acclaimed him. They needed heroes, and they found a great one in John Paul Jones.