Although Germany’s rearmament plans were alarming enough, the Air Staff were confident that the Germans would not be in a position to offer a serious challenge to Britain in terms of first-line air power until at least the end of 1936. This belief, however, was based on the assumption that there would be no dramatic increase in the rate of German aircraft production; if such an increase took place, the Air Staff were well aware that the Germans had the capability to build up a combat force of two thousand aircraft, with reserves, in a relatively short time. Air Chief Marshal Sir Edward Ellington, who had taken over the post of CAS in May 1933, stated this danger in very clear fashion at a Chiefs of Staff Committee meeting on June 1934.

Parliament, however, seemed unable to grasp the sense of urgency. It was absent even in November 1934, when – since it was by then apparent that the Germans had no intention of limiting their arms production – Baldwin told the House that although further increases would be necessary in the strength of the RAF’s metropolitan air force, it would not be difficult for Britain to maintain the necessary degree of air superiority.

One of the major reasons for the British Government’s dangerously optimistic attitude was that even at this late stage, its diplomatic representatives were still seeking to achieve the limitation of air power in Europe by means of a proposed air pact between the signatories of the Locarno Treaties. Italy, Germany and Belgium were invited to take part in the negotiations, and the immediate German reaction was to ask for representatives of the British Government to visit Berlin. It was when the British emissaries – Sir John Simon and Anthony Eden – arrived in the German capital in March 1935 that the first big shock came; during an early meeting with Hitler they were informed that Germany already had an air force equal in first-line strength to Britain’s home-based force, and that before long equality would have been achieved with France’s combined metropolitan and North African air forces. In numerical terms, that meant up to 2000 aircraft – the number predicted by Sir Edward Ellington nine months earlier.

The light of history has shown that the German claim to parity in air power with Britain was false at the time it was made, even though the prediction of future equality with France was accurate enough. In March 1935 the Luftwaffe possessed twenty-two squadrons and about 500 aircraft, 200 of which were operational first-line types. The British Cabinet, however, was not aware of this and the report submitted by Sir John Simon and Anthony Eden on their return from Berlin was taken very much at face value. The alarm it caused within the Cabinet was considerable, particularly since it came in conjunction with other reports – this time fully substantiated – that the Germans were building up an efficient civil defence system and that Berlin had already experienced an air-raid warning exercise involving a trial blackout.

To carry out a full investigation into the growth of German air power, the Cabinet appointed a special committee under the initial chairmanship of Sir Philip Cunliffe-Lister. The findings of this committee showed that the position was more serious than had previously been supposed. The Secretary of State for Air, Lord Londonderry, had already been urging a reorganization of the British aircraft industry so that its production lines would be geared up to meet the demand of a rapid increase in RAF aircraft strength. The Air Staff, for their part, now realized that Expansion Scheme A was inadequate in the light of what was known of Germany’s plans; they were, however, not in favour of a crash expansion programme, as the equipment available to implement such a scheme at that time was for the most part obsolescent. The feeling was that it was better to aim for a gradual expansion based on the new range of combat aircraft then on the drawing board or flying in prototype form, with a strength of about 1500 first-line machines by 1937 as the target.

The new plan – known as Scheme C – was laid before both Houses of Parliament on 22 May 1935. It called for a home-based force of sixty-eight bomber squadrons and thirty-five fighter squadrons, to be ready by March 1937. One-third of the bomber force, about 200 machines, was to consist of aircraft with sufficient range to reach targets in the Ruhr from British bases; the remainder would be able to achieve this only by operating from advanced bases on the Continent.

Seventeen of the new squadrons had been formed by April 1936 and, to accommodate the further increases envisaged, thirty-two new RAF stations were being constructed in the British Isles. Meanwhile, in February 1936, Scheme C had been supplanted by Scheme F, under which a front-line force of 1736 aircraft was planned for 1939. This was to be made up of twenty heavy-bomber squadrons, forty-eight medium bomber, two torpedo-bomber, thirty fighter and twenty-four reconnaissance, with an additional thirty-seven squadrons based overseas. Scheme F was of particular importance because it laid considerable emphasis on the provision of reserves; front-line squadrons were to have a minimum of seventy-five per cent reserves available for immediate use, and there was to be a further reserve of 150 per cent available to maintain the RAF at full combat strength in the event of war.

Until the new light and medium monoplane bombers became available in quantity, the mainstay of the RAF’s bomber force was the Hawker Hind biplane. Designed as a replacement for the ageing Hawker Hart, the Hind first flew in September 1934 and entered service with Nos. 18, 21 and 34 Squadrons at Bircham Newton towards the end of 1935. Hinds subsequently equipped twenty-five home-based bomber squadrons up to 1938, and was used by eleven Royal Auxiliary Air Force units for some time after that.

The Hind was in reality an interim aircraft, filling the gap between the Hart and the first of the monoplane bombers: the Fairey Battle. The prototype Battle flew on 10 March 1936, powered by a Rolls-Royce Merlin engine, and production of an initial batch of 155 machines began in May of that year. In May 1937, the first Battles were delivered to No. 63 Squadron at Upwood, and aircrew were enthusiastic about the aircraft’s clean lines and its ability to carry a 1000-pound bomb load. Nevertheless, the Battle was underpowered and sadly lacking in defensive armament, two serious drawbacks that were to remain with it throughout its operational career, resulting in a fearful rate of attrition when the type was sent into action during the early stages of the Second World War.

A far more promising aircraft was the twin-engined Bristol Blenheim medium bomber, which had its origin in the Bristol 142 ‘Britain First’, ordered as a transport by Lord Rothermere and later presented to the Air Ministry. An order for 150 Blenheim Is was placed in August 1935 and the prototype flew ten months later, on 25 June 1936. The first production machines were completed at Bristol’s Filton factory towards the end of that year and went into service with No. 114 Squadron at Wyton early in 1937.

When it first made its appearance, the Blenheim was a good 40 mph faster than the biplane fighters that equipped Europe’s air forces. Its maximum speed of 285 mph, coupled with its ability to carry a 1000-pound war load as far as German targets, represented a sensational advance in the design of bomber aircraft and in 1936 the Air Ministry placed follow-on orders for 1130 more. Production of the Blenheim Mk. 1 went ahead very rapidly and by 1938 the type was available in sufficient numbers to permit the re-equipment of RAF bomber squadrons in India, Iraq and Egypt.

Two more ‘interim’ bomber aircraft which formed part of the mid-1930s expansion scheme were the Vickers Wellesley and Handley Page Harrow. The Wellesley was a revolutionary aircraft in more ways than one. The brainchild of Rex Pierson and Barnes Wallis, it featured geodetic construction; a method consisting of comparatively light strips of metal forming a web of the aeroplane’s wings and fuselage, first pioneered by the Vickers team in the R.100 airship. This type of structure resulted in a weight saving of about forty per cent, giving the aircraft a satisfactory performance on the power of a single Bristol Pegasus engine – an unusual layout for a machine designed as a long-range medium bomber. Two thousand pounds of bombs were carried in two containers under the aircraft’s long wings, and defensive armament consisted of one Vickers machine-gun in the port wing and a second mounted in the rear cockpit. Range was 2590 miles, but in November 1938 two Wellesleys of the RAF Long Range Development Unit, stripped of their military equipment and with extra fuel tanks, made a record-breaking non-stop flight of over 7157 miles from Ismailia to Darwin. A third aircraft also set off, but was forced to land on the island of Timor. Before production ended in 1938, 158 Wellesleys were built, equipping six medium-bomber squadrons in the United Kingdom and three abroad.

The Handley Page Harrow was a very different aircraft. Originally developed as a night bomber, it was eventually selected by the Air Ministry to meet a requirement for a bomber-transport and one hundred machines were ordered in August 1935. Delivery of production Harrows began in April 1937 and the type equipped Nos. 37, 75, 115, 214 and 215 Squadrons until it was finally replaced by more modern equipment in 1939. Powered by two Pegasus engines, the Harrow had a top speed of 200 mph, a range of 1250 miles and could carry a bomb load of 3000 pounds.

The mainstay of the RAF’s heavy-bomber force during the expansion period was the four-seat Handley Page Heyford biplane, designed in 1927 to replace the Hinaidi and the Vickers Virginia. Powered by two Rolls-Royce Kestrel engines, the first Heyford flew in June 1930 and production machines entered service with No. 99 Squadron at Upper Heyford in December 1933. The aircraft could carry up to 3500 pounds of bombs and was armed with three Lewis machine-guns. Heyfords served with eleven RAF bomber squadrons until 1937, when they began to be progressively phased out in favour of new monoplane bomber types.

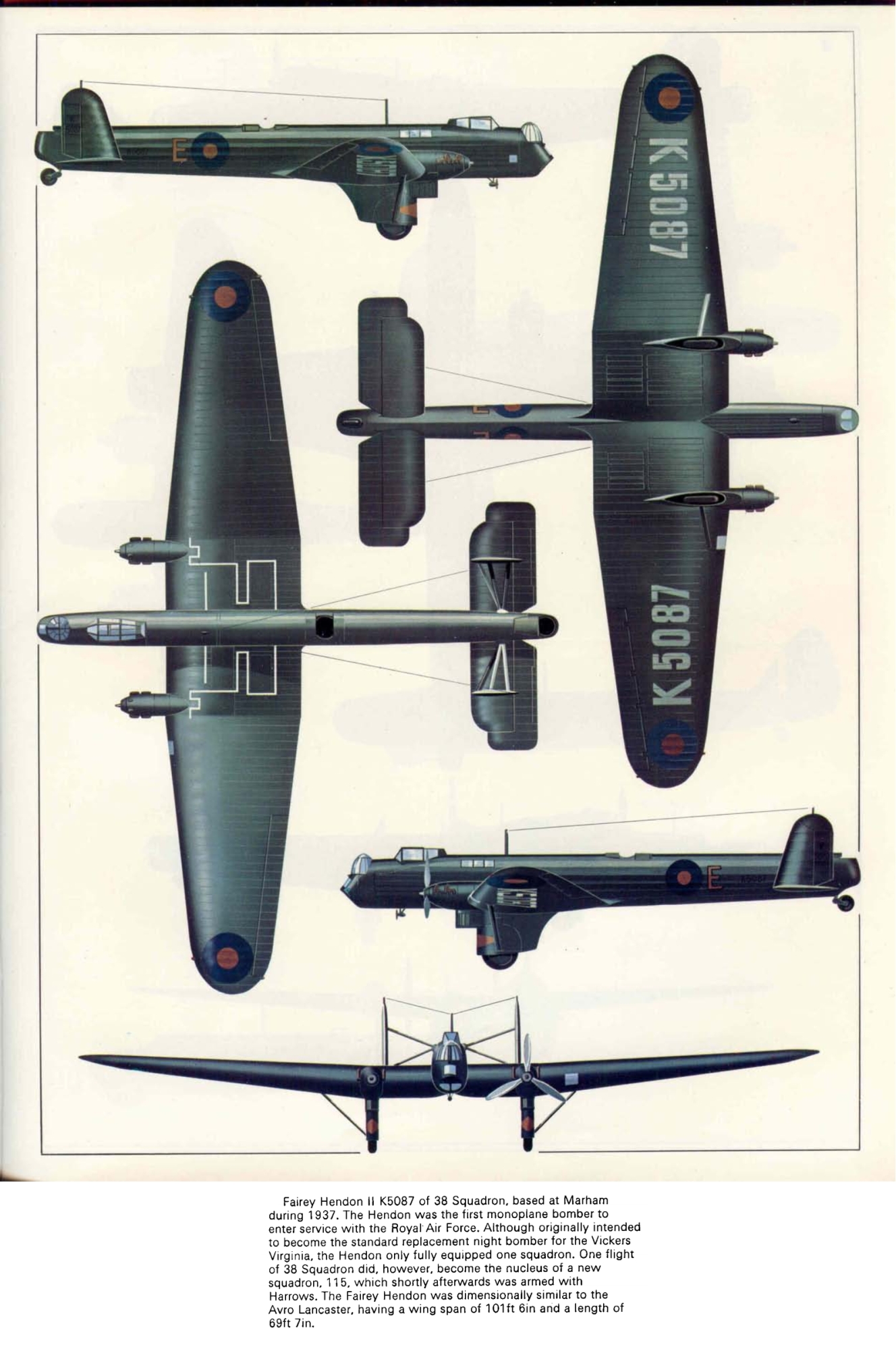

The other aircraft designed to the same specification as the Heyford was the Fairey Hendon, which was selected in 1934 to be the main RAF heavy-bomber type. An ugly-looking low-wing monoplane with twin fins, the Hendon prototype made its first flight in November 1931 powered by two Bristol Jupiter VIIIs but a lot of trouble was experienced with these, and later aircraft were fitted with Kestrels. The Hendon entered service with No. 38 Squadron at Mildenhall in November 1936, but by this time the prototypes of more advanced bombers were already flying and only fourteen production Hendons were built, an order for a further sixty being cancelled. In June 1937, No. 38 Squadron detached one of its Hendon flights to Marham; this formed the nucleus of No. 115 Squadron, which re-equipped with Harrows shortly afterwards.

On 14 July 1936 Royal Air Force Bomber Command was formed, with its headquarters at Uxbridge. Initially, the Command consisted of four Bomber Groups, Nos. 1, 2, 3 and 6, the last being an Auxiliary Group. By this time the Air Ministry was giving priority to the design and production of heavy bombers at the expense of light bombers and even medium types. The requirement now was for maximum range and maximum bomb load.

The first of the new heavy bombers was the Armstrong Whitworth Whitley. Designed to specification B.3/34, the Whitley prototype flew on 17 March 1936 and a contract for eighty production aircraft was placed in August 1935. The first squadron to receive Whitley Mk. Is was No. 10 at Dishforth in Yorkshire, deliveries beginning in March 1937, and the aircraft also went into service with No. 78 Squadron at the same station the following July. Thirty-four Mk. Is were built, and these were followed by forty-six Mk. IIs which entered service with Nos. 51, 58 and 97 Squadrons from January 1938.

A second contract, placed in 1936, led to the production of eighty Whitley Mk. Ills, and delivery of these machines to operational squadrons began in August 1938. All Whitley variants so far had been powered by two Armstrong Siddeley Tiger engines, but after the Mk. III a changeover was made to Rolls-Royce Merlins. The last Whitley version to go into service before the outbreak of war was the Mk. V, which became operational with No. 77 Squadron at Driffield, Yorkshire, in August 1939. The Whitley V had a maximum speed of 230 mph at 16,400 feet, an operational ceiling of 26,000 feet and a range of 2400 miles. It could carry a maximum bomb load of 7000 pounds, and defensive armament consisted of one Vickers gun in the nose turret and four Brownings in the tail turret.

The other two heavy-bomber types which, together with the Whitley, were to form the backbone of the RAF’s strategic bombing force on the outbreak of the Second World War – the Handley Page Hampden and the Vickers Wellington – were both designed to Air Ministry Specification B.9/32. Only a matter of days separated the first flights of the respective prototypes of these two machines, the prototype Wellington flying on 15 June 1936 and the Hampden on 21 June.

An order was placed for 180 Wellington Is, powered by two Bristol Pegasus XVIII engines, and the first of these were delivered to No. 99 Squadron at Mildenhall on 10 October 1938. By August the following year eight squadrons of Wellingtons were operational with No. 3 Group in East Anglia. Like the earlier Wellesley, the Wellington was of geodetic construction, which enabled it to withstand fearful punishment when it was put to the test in combat. The aircraft’s maximum speed was 255 mph at 12,500 feet, and range was 2200 miles with a 1500-pound bomb load.

The Wellington’s contemporary, the Hampden, showed outstanding promise during its early flight trials. Air Ministry experts liked the machine’s radical design; the deep, narrow fueselage with its high single-seat pilot’s cockpit; the slender tail boom supporting twin fins and rudders; the long, tapering wings with their twin Pegasus radial engines. The view from the pilot’s seat was exceptionally good, and the Hampden possessed almost fighter-like manoeuvrability; an important factor and one which, coupled with its maximum speed of 265 mph at 15,500 feet, the experts believed would give it more than a fighting chance of survival during daylight operations in a hostile environment. The Hampden’s main disadvantage, in fact, appeared to be that the crew’s positions in the three-foot-wide fuselage were far too cramped to permit any degree of comfort, and this resulted in excessive crew fatigue. The defensive armament of four hand-operated machine guns was also inadequate, as Hampden crews were to learn to their cost during early war flights over enemy territory.

Such, then, was the equipment available to Bomber Command during the latter part of the troubled 1930s; the sharp edge of the sword which, it was still fervently hoped, would act as a deterrent to the growing air might of Nazi Germany. Early in 1937, the Air Ministry realized that if the Luftwaffe continued to expand at its present rate the provisions of Scheme F would not be sufficient to maintain first-line parity in 1939, as had been planned; accordingly, a revised plan – Scheme H – was submitted to the Cabinet. This called for an increase in the RAF’s metropolitan first-line force to nearly 2500 aircraft at the earliest possible date after April 1939, and the total figure was to include 1659 bombers. The increase was to be made possible by drastically cutting down the number of machines in reserve and channelling them into first-line units.

Although this would have given the RAF numerical equality with the anticipated first-line strength of the Luftwaffe, it would also have meant that obsolescent aircraft would have been committed to battle in far greater numbers when war came than was actually the case. This, however, was not the principal reason why the Cabinet rejected the new scheme; they did so mainly because of German assurances that the limit of the Luftwaffe’s expansion would be much lower than the British feared. And this at a time when, in Spain, German and Italian air force units were already in training for the war!

It was nevertheless clear to the Cabinet during the spring of 1937 that, with the threat to European peace posed by the activities of Germany and Italy, and the potential threat to peace in the Far East created by the expansionist aims of Japan, the whole question of Britain’s defence policy was in need of review. Defence thoughts so far had been dictated by the prospect that Britain would have to cope with one enemy – first France, and then Germany – and now it looked as though she might find herself faced with three at the same time.

To reconsider the whole area of defence, a Defence Plans (Policy) sub-committee was set up and Sir Thomas Inskip appointed to the new post of Minister for the Co-ordination of Defence. The sub-committee’s first task, in July 1937, was to instruct all three armed services to make an exact assessment of their present and future requirements so that accurate estimates of the cost of their respective re-equipment programmes might be made. The immediate reaction of both Army and Navy was to submit greatly inflated estimates of the cost of their future programmes in the hope that more funds might be allocated to them; to counter this move, in October, the Air Ministry submitted the most detailed expansion plan so far.

Under the proposals outlined in the new plan – Scheme J – Bomber Command’s strength was to be increased to ninety squadrons, with 1442 aircraft. These squadrons were to be progressively re-equipped with a second generation of monoplane heavy bombers: large four-engined machines, still in the design stage in 1937, which would be capable of carrying more than twice the bomb load of the Whitley, Hampden and Wellington and over a considerably greater range. The scheme, which was to reach completion by the beginning of 1943, was to cost £650 million – an increase of £183 million over the original estimated cost of Scheme F.

After considering the new scheme, however, Sir Thomas Inskip informed the Secretary of State for Air that he proposed to reject it mainly on the grounds that he believed the Air Staff’s emphasis on strategic bombing as a means of winning a war to be misplaced. He believed that if war came with Germany, the decisive factor in the first few weeks would be the fighter aircraft. Priority should be given to strengthening Fighter Command to the point where it would be capable of winning a decisive victory over the Luftwaffe bomber forces that the Germans might be expected to commit to a large-scale air offensive against Britain. This would gain vital time and allow a war of attrition to develop, in which the Royal Navy could exploit its command of the sea to the full by imposing a blockade on the enemy.

Inskip’s view was that Germany’s air strength could be destroyed more effectively in combat with Fighter Command over Britain than by the Air Staff’s policy of sustained attacks against the German aircraft industry and operational airfields. What he proposed was a drastic reduction in the proposed strength of Bomber Command, with large cuts in the bomber reserves and a concentration on the development of light and medium bombers rather than on long-range heavy bombers. He considered that the Air Staff should give up any idea of attempting to reach parity with the Luftwaffe in terms of numbers. Apart from the fact that the possibility of achieving parity was fast receding, the operational requirements of the Luftwaffe and the RAF were so different as to make it unnecessary. The Luftwaffe’s aim was the creation of a large tactical bombing force to support the Wehrmacht, whereas the RAF’s main need was for a strong fighter force to defend Britain herself, and if necessary to establish air superiority over the battle-field.

Although this view provoked a predictably hostile reaction from the Air Staff, it was nevertheless accepted by the Cabinet in December 1937 and the estimated cost of implementing Scheme J was drastically slashed to £100 million. Together, the Air Ministry and Sir Thomas Inskip hastily thrashed out a new plan – Scheme K – in which it was decided that the money would be allocated to the retention of the fighter strength envisaged in Scheme J, while cutting down the number of first-line bomber squadrons and reserves. Progressive re-equipment of Bomber Command with new types of heavy bomber would go ahead, but much more slowly than planned.

The resulting picture was a gloomy one. At an Air Staff meeting held on 18 January 1938 the CAS pointed out that the changes recommended in Scheme K meant that the RAF would have only nine weeks’ reserves, and if war came the full potential of the aircraft industry would not have time to develop. He saw the provision of more heavy-bomber reserves as a vital necessity, but to achieve this object with the funds allocated under Scheme K presented an apparently insurmountable problem. The only possible solution appeared to lie in effecting a saving by making cuts in other areas, notably training schools.

That the Air Ministry was prepared to consider such a step was proof enough of the extent to which the situation had deteriorated. Despite the advice of the Air Staff, despite an increasing wave of public criticism, the Government still had its head firmly in the sand as far as the air defence needs of this country were concerned. It was only in March 1938, when German troops marched across the border into Austria, that the Cabinet was galvanized into action. Scheme K was quietly forgotten and replaced by Scheme L, which was drawn up under conditions of near panic that same month. This envisaged the rapid expansion of the RAF’s strength to 12,000 aircraft over a period of two years, should war make it necessary, but the emphasis was still on fighter production and there was still no provision to increase the strength and efficiency of Bomber Command to the point where it could launch an effective counter-attack on Germany.

It was in September 1938, at the height of the Munich crisis, that the tragically weak position of Britain’s armed forces – and particularly of RAF Bomber Command – was made brutally clear. Six years earlier, Britain’s failure to maintain strong offensive forces had helped to weaken her power to negotiate at the Geneva Conference, and now history repeated itself – with infinitely more serious consequences for Europe and the world – as Britain, France and Germany haggled over the Sudetenland. France and Britain threatened war if the Sudetenland was annexed, but in Britain’s case at least it was an impotent threat. As far as the RAF was concerned, only one hundred Hurricanes and a mere six Spitfires had as yet reached Fighter Command’s first-line squadrons, and although forty-two Bomber Command squadrons were mobilized thirty of them were equipped with light and medium bombers of insufficient range to reach German targets from British bases. Worse still, a critical shortage of spares meant that less than half this force was ready for combat; reserves amounted to only ten per cent, and there was a reserve of only 200 pilots.

It is a matter of history that in 1938, the Luftwaffe was not in a position to launch a large-scale air offensive against the British Isles. Because of the limited range of its bomber aircraft, such a plan could only be put into action with the capture of air bases in France and the Low Countries, and the tanks with which the German Panzer divisions smashed their way westwards in the spring of 1940 were not then available in sufficient numbers to make a ‘blitzkrieg’ practical in 1938. It is also a matter of history that if France – whose army was still numerically superior and in some respects better equipped than the Wehrmacht – had taken the initiative and invaded Germany in 1938, her chances of success would have been more than favourable.

This fact, however, and the fact that – if war had come in 1938 – the Luftwaffe would have been incapable of taking reprisals for any strategic RAF raids on Germany, were totally eclipsed by the Allies’ frantic desire to buy time almost at any cost. As they bartered Czechoslovakia in return for a few months’ respite, Chamberlain and his colleagues in the British delegation could think of the relative strengths of the RAF and the Luftwaffe only in terms of numbers, and in the light of these statistics Britain’s air striking power seemed distinctly inferior to that of her potential opponent. Greatly exaggerated German claims about the Luftwaffe’s strength were accepted at face value and there was little that either the British or French politicians could do to dispute Hitler’s bluff, for accurate intelligence on the organization of the Luftwaffe and the performance of its latest combat aircraft was practically non-existent. Although it was known that modern German fighters and bombers were operating on the Nationalist side in Spain, the full extent of their commitment to this conflict was not realized; nor was the fact that regular Luftwaffe air and ground crews were being rotated for Spanish duty under conditions of great secrecy. A golden opportunity to assess the quality of the Luftwaffe’s men and machines at first hand, and to observe the air tactics which were to take the Allies completely by surprise in 1940, was consequently wasted.

On the other hand British Intelligence had, at the time of Munich, a reasonably accurate picture of potential targets vital to a German war effort. The means by which this information was acquired had been extensively reviewed in 1936, when an Industrial Intelligence Centre had been set up under the direction of Major D. F. Morton. The Centre’s primary task was to assemble every scrap of information which, in the event of war, would enable plans for a crippling economic blockade of Germany to be put into action quickly. The information collated by the Industrial Intelligence Centre, and that from other intelligence sources, was turned over to the Air Ministry; there it was co-ordinated by the Deputy Director of Plans, Group Captain John Slessor, whose staff was responsible for arranging selected targets in order of priority for Bomber Command.

In the autumn of 1937, the broad priorities that would govern Bomber Command’s air offensive had been set down in thirteen directives known as Western Air Plans, approved at an Air Ministry conference on 1 October. At the head of the list was plan W.A.1, which envisaged a major air strike on the Luftwaffe’s bomber force and its maintenance organization; W.A.2 and W.A.3 involved co-operation between Coastal Command and the Royal Navy, while W.A.4 called for a bombing offensive against German rail, road and canal communications with the object of hindering an advance into France and the Low Countries by German forces. W.A.5 was the blueprint for an attack on Germany’s war industry in the Ruhr, Rhineland and Saar, with particular reference to oil installations; W.A.6 was a plan for attacking manufacturing resources in Italy; W.A.7 envisaged bombing attacks on the enemy fleet and its bases in co-operation with the Navy, with the big Kriegsmarine base at Wilhelmshaven as the primary target; W.A.8 was a scheme for attacking various kinds of enemy supply depot; W.A.9 was a tentative plan for putting the Kiel Canal out of action, subject to the availability of bombs large enough to do the job; W.A.10 was another co-operative plan between Bomber Command and the Royal Navy, with shipping and German merchant ports in the Baltic area as its main objective; W.A.11 was a scheme for the destruction of large tracts of German forest by incendiary bombing; W.A.12 was a plan for attacking units of the enemy fleet at sea; and W.A.13 envisaged precision raids against administrative centres and other headquarters in Berlin and other major German cities.

A searching review of Bomber Command’s capability following the Munich crisis revealed that the three Western Air Plans to which priority had been allocated – W.A.1, 4 and 5 – could not be undertaken with any real hope of success at this stage. It was unlikely that Bomber Command could inflict any substantial damage on the Luftwaffe by an offensive against those German aerodromes already targeted by the Air Ministry Plans Division for the simple reason that the Germans were building large numbers of emergency airstrips on which their bombers would be deployed before the outbreak of hostilities, and the locations of most of these were not known. Also the C-in-C Bomber Command, Sir Edgar Ludlow-Hewitt, informed the Air Ministry that a sustained attack on the German aerodromes as envisaged in W.A.1 would in all probability result in the complete annihilation of his medium- and heavy-bomber forces in a matter of weeks. Assuming that Holland and Belgium remained neutral, such an offensive would have to be undertaken mainly by the Blenheim and Battle squadrons operating from French airfields, and of the two aircraft types only the Blenheims would stand anything like a fighting chance of getting through to their German targets. Crippling losses might only be avoided if the bombers were escorted by long-range fighters, and as yet no aircraft of this kind had been developed for RAF use.

It was also realized that Bomber Command would encounter overwhelming obstacles in the execution of W.A.4, the plan to attack German communications to slow up an invasion of France and the Low Countries. The main obstacle here was a difference of opinion between the Air Staff and the General Staff on the type of target to be attacked; the General Staff favoured a concentration on railway bridges and viaducts, while the Air Staff believed that better results could be achieved by attacks on railway stations and junctions. Whichever stratagem was adopted, however, both Air Staff and General Staff were agreed on one point: it would involve the commitment of almost the whole of the medium-bomber force based on the Continent and would result in severe losses – and, because of the mass of rail and road systems available to the enemy, its success was bound to be strictly limited.

There remained, therefore, only one Air Plan which Bomber Command might put into action with any hope of success: W.A.5, an attack on Germany’s war industry. In a report made to the Air Ministry, the Air Targets Sub-Committee of the Industrial Intelligence Centre had indicated that the German war effort could be crippled by a sustained bombing offensive in the first weeks of the war against forty-five selected power stations and coking plants in the Ruhr. The Air Ministry, however, realized that this report was based on the assumption that Bomber Command could find and hit these targets every time; an assumption which, taking into account existing navigational and bombing techniques, was very far removed from reality. The Air Ministry view was that it would be more profitable to concentrate on the destruction of two major targets on which much of the Ruhr’s industry depended: the Möhne and Sorpe dams. Again, this plan could not be activated until Bomber Command had sufficiently large bombs at its disposal. Meanwhile, considerable disruption of the enemy’s war effort could be achieved by attacks on the canal system which connected the Ruhr with northern Germany.

There was, however, a major obstacle in the path of the plan to attack German industrial targets. On 21 June 1938, the Prime Minister had announced in the House of Commons that only military targets would be attacked by the RAF, and that every possible care would be taken to avoid civilian casualties. This immediately gave rise to a problem of definition; could, for example, a factory producing military equipment as well as other materials be classed as a military objective? Despite the difficulty in determining what was a military objective and what was not, the principle of a restriction on strategic bombing was generally viewed favourably in Parliament, mainly because it was thought that such a restriction would be to Britain’s advantage as it would give the potential enemy no excuse to attack targets in British cities. Accordingly, Sir Edgar Ludlow-Hewitt was ordered to take no action to execute W.A.5 in the event of war; instead, Bomber Command was to confine its initial activities to carrying out W.A.1 and W.A.4 – both of which had already been assessed as unsatisfactory, as we have seen.

The initiative, therefore, was handed to the Germans. Only if the Luftwaffe embarked on a policy of unrestricted strategic bombing could Bomber Command retaliate by attacks on German industrial targets. If strategic attacks by the Luftwaffe did not materialize, the best course for Bomber Command to follow – as Sir Edgar Ludlow-Hewitt was informed in an Air Council letter dated 15 September 1938 – was to conserve its strength in view of the slender reserves available, rather than fritter away its resources in carrying out either W.A.1 or W.A.4 in return for a result that would probably be negligible.

Meanwhile, although all too conscious of the fact that Bomber Command’s ability to penetrate into industrial Germany was poor, and would remain so until the new four-engined bombers entered service, the Air Staff continued to work on W.A.5, extending it to include a wider variety of targets. Among the new objectives now being considered were German oil plants and refineries, many of which were situated in western Germany and therefore within range of existing RAF bombers operating out of bases in Britain.

Useful though these considerations were to be in the long run, they did nothing to solve the immediate problem of the manner in which Bomber Command was to be employed if war broke out. Attacks on the German Fleet were, of course, outside the bombing restriction, and it was decided that these would be among Bomber Command’s priorities in the first days of war. Another scheme involved the dropping of propaganda leaflets over Germany and this crystallized into Air Plan W.A.14, a co-operative venture on the part of the Air Ministry, the Foreign Office and the Stationary Office.

By March 1939 it was clear to both the British and French Governments that the policy of appeasement towards Hitler’s Germany no longer held good. Somewhat belatedly, the British and French General Staffs now met to work out a common defensive policy in view of the increasing aggressiveness of the Axis powers; the German absorption of Czechoslovakia in March had been followed rapidly by the Italian invasion of Albania during the first week of April, and the probability that Britain and France would be drawn into war if Hitler turned his armed might on Poland now loomed large. It was decided that a British Expeditionary Force, together with an Air Component, should be sent to France; the Air Component would be given full facilities on French airfields on the understanding that its aircraft would not be used for unrestricted bombing of German targets from these bases. France, unlike Britain, was vulnerable to heavy attacks by Luftwaffe medium bombers based on German territory, and the French Government’s fear of large-scale reprisal raids by the German Air Force was considerable. The French General Staff insisted that the British air component in France must be employed in full to hold up a probable advance by German ground forces, and the British Air Staff – although the shortcomings of Air Plan W.A.4 were well known – had little alternative but to agree.

Even then, the Air Staff and the French General Staff could not reach a firm agreement on how best to use the British bombers in the effort to stem a German drive westwards. The French wanted the RAF to attack German columns, railway communications and airfields; the Air Staff, considering the inadequacy of the equipment at its disposal in the light of the heavy fighter and anti-aircraft opposition that was likely to be encountered, were still sceptical that any favourable result could be obtained. In the end the Air Staff, while promising that the RAF bombers would be used to the fullest advantage in support of the Allied ground forces, warned the French General Staff not to expect too much help from this quarter.

The question had still not been resolved when, on 1 September 1939, the Wehrmacht stormed over the frontier into Poland, a path blasted ahead of it by the Luftwaffe’s bombers. A week earlier, on 24 August, No. 1 Group – comprising most of Bomber Command’s Fairey Battle squadrons – had been ordered to mobilize in readiness to go to France as an advanced air striking force. The Group had been held at a high state of alert ever since the Munich crisis, and the new order to mobilize came immediately following the news that Germany and the Soviet Union had signed a non-aggression pact; a step that made Germany’s intentions all too clear with regard to Poland. In the early afternoon of 2 September ten Battle squadrons – 160 aircraft in all, led by No. 226 Squadron – flew in impeccable formation over the English coast near Shoreham, on course for their new bases in France. They made an impressive sight and the crews were in high spirits.

Less than twenty-four hours later, Great Britain was at war with Germany.