The story of German military aviation stretches back to the end of the nineteenth century, when a small balloon section was established during November 1883, initially incorporated into a railway troop but becoming autonomous after four years. Experimental large rigid airship designs developed by former Army Officer Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin eventually steered an almost reluctant military towards airships, while in 1908 the German General Staff concluded that the aeroplane must also become part of the future military arsenal. Within two years a flying school was formed in Döberitz and the first military aircraft acquired by the German Army entered service, forming the nucleus of the Fliegertruppen des deutschen Kaiserreiches (Imperial German Flying Corps), which in October 1916 would become the Deutsche Luftstreitkräfte (German Air Combat Forces).

Successful Army experiments with balloon reconnaissance also led the German Navy to reopen investigations into their viability after initial trials had been cancelled in 1890. Their primary role was to be scouting for enemy units and minefields, roles traditionally carried out by destroyers and high-speed small craft. However, communications failures between a torpedo boat and the crew of its towed balloon during trials near Kiel led to the cancellation of all attempts at developing aerial reconnaissance. The decision resonated with Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz, Secretary of State of the Imperial German Naval Office, who had previously dismissed the idea out of hand as contrary to his faith in surface ships fulfilling this purpose.

But for the enthusiasm for naval aviation of Prince Heinrich of Prussia, younger brother to the Kaiser, Wilhelm II, the matter may have rested there. Heinrich, promoted to the rank of Großadmiral on 4 September 1909 after thirty-eight years of naval service, was arguably more popular than his older brother, particularly abroad, where his diplomatic skills far surpassed those of Wilhelm. Heinrich, in his role as Inspector General of the Imperial Navy, attended the Döberitz flying school and graduated as Germany’s first naval pilot determined to develop a seaplane force. He remained instrumental in the development of naval aviation, unmoved by Tirpitz’s general disapproval of the diversion of resources that included a 200,000-Mark investment by the Reichsmarineamt which he considered better used by the surface fleet. Meanwhile, after British naval authorities enquired about the purchase of German-made Zeppelins, Germany was finally spurred into the building of their first naval airship, L1, which was ready for testing in October 1912. Following successful trials, the Navy Airship Detachment (Marine Luftschiffabteilung) was formed on 8 May 1913 under the command of Korvettenkapitän Friedrich Metzing.

However, the entire German airship project soon suffered two heavy blows. Metzing and fifteen of his crew were killed when L1 crashed in high winds during fleet manoeuvres in September 1913, and the second airship commissioned, L2, exploded at altitude, killing all on board. Nonetheless, the new commander of the Airship Detachment, Kaptlt. Peter Strasser, was able to steer his fledgling unit through the minefield of critics determined to see the airship programme aborted, and L3 took to the skies in May 1914.

Parallel to Strasser’s airship unit was the Naval Flying Detachment (Marine Fliegerabteilung) which had been established in 1911 following Heinrich’s graduation as a pilot. Early trials were made using civilian aircraft on loan, as initial expectations of interest from German aircraft manufacturers proved misplaced. Seaplanes were far more expensive and specialised to construct than land-based aircraft, and naval specifications demanded that all naval aircraft be amphibious. This, combined with the fact that the majority of manufacturers were located considerable distances from Germany’s coastline, conspired to keep the fledgling service arm impoverished. It was not until May 1912 that the first pair of German-built Albatros B1 two-seat reconnaissance aircraft were received by the Naval Air Service.

Nevertheless, the detachment gradually grew in size and the pace of seaplane development increased. An experimental centre for naval aviation was established in West Prussia near Putzig, forty-four kilometres north of Danzig. Boasting a concrete slipway, an 800m airstrip and all necessary buildings and workshops for a functioning airfield, the first aircraft, a Fritzsche Rumpler, arrived to be equipped with floats during the autumn of 1911. On 3 May the following year an Albatros D 2 took off from the solid runway and successfully alighted on water, as it had been decreed that all German naval aeroplanes were to be of amphibian configuration. This, however, was a difficult requirement to meet owing to the weight of a dual float-and-wheel assembly and the marginal engine power then available. By discarding the wheels fitted to the central Coulmann float of the Albatros WD 3 (70hp Mercedes), Oblt.z.S. Walter Langfeld was able to make the first water take-off on 5 July 1912. When the wheels were fitted again, a system was used that enabled them to be raised clear of the water. To reduce water resistance further and allow acceleration to flying speed, the wingtip floats could also be raised by means of a large handwheel on the port side of the engine nacelle. However, official dissatisfaction with the slow progress of the marine aeroplane led to the first German Seaplane Competition, held at Heiligendamm in August-September 1912. Various manufacturers submitted what were basically landplanes fitted with floats, and although only two (Aviatik and Albatros) met the stated requirements, the official view was that the problems of amphibious operations had been solved.

On 1 June 1913 the 1.Marine Flieger Abteilung was formed in Kiel- Holtenau with a complement of 100 officers and men. To evaluate current foreign marine aircraft techniques, several machines were bought from other countries, including an Avro 503 seaplane from Britain. Following acceptance tests, Langfeld flew the Avro to Heligoland in September 1913 for the autumn fleet manoeuvres, carrying a passenger; the first flight by a seaplane from the German mainland to Heligoland. Four seaplanes were deployed in the manoeuvres, three of which were considered unsuitable for operational use, but the Avro produced excellent results. Meanwhile, the production of a single-engine biplane with floats, the Friedrichshafen FF 29, began at Flugzeugbau Friedrichshafen, and the FF 29 entered service with the Imperial German Navy in November 1914, by which time the nation had been at war for four months. That same month Oblt.z.S. Friedrich von Arnauld de la Perrière, brother of the soon-to-be famous U-boat commander Lothar, was placed in command of the first German naval air unit deployed on foreign soil after he established Seeflugstation Zeebrugge on the harbour mole. A former passenger terminal was converted to form the core of the seaplane base, with hangars, ammunition storage and personnel quarters added or requisitioned. A railway spur linked the base with Lisseweg, where German forces had established a major aircraft repair facility.

The Marine Flieger Abteilung began the war with a strength of only twelve seaplanes; six in Heligoland, four in Kiel (to where the detachment had moved its headquarters) and two in Putzig; between them mustering thirty officer and three NCO pilots, with few trained observers. Naval air observers (land or sea) did not have to hold commissioned rank, as was required in the Army Air Service. Although underequipped and predominantly relegated to reconnaissance, with limited attacks on enemy shipping, the naval aircraft detachments gradually grew in strength, as did Strasser’s airship numbers as they proved their worth both in reconnaissance and as part of the aerial bombardment of Great Britain, authorised by the Kaiser in January 1915. Indeed, Strasser was a known advocate of area bombing, writing to his mother after the commencement of Zeppelin raids on British cities:

We who strike the enemy where his heart beats have been slandered as baby killers and murderers of women. What we do is repugnant to us too, but necessary. Very necessary. A soldier cannot function without the factory worker, the farmers, and all the other providers behind them. Nowadays there is no such animal as a non-combatant; modern warfare is total warfare.

Germany fielded seventy-eight naval airships during the First World War which flew a combined total of 1,148 reconnaissance missions and hundreds of bombing raids, delivering 360,000kg of bombs, the majority against British harbours, ports, towns and cities. Strasser had been named Führer der Luftschiffe (F.d.Luft) and continued to fly combat missions until he was killed on 5 August 1918 during a raid on Boston, Lincolnshire, when his airship, L70, was shot down near the Norfolk coast by a British D.H.4. aircraft, all twenty-three men aboard being killed.

Nordholz, near Cuxhaven on the North German coast, was the main naval airship base and F.d.Luft headquarters, with subsidiary bases on the North Sea coast and within the Baltic. Small numbers were also employed within the Adriatic and Black Seas, and L59 attempted a supply journey from Bulgaria to East Africa, turning back at Khartoum when the planned rendezvous area with German troops was overrun by British forces.

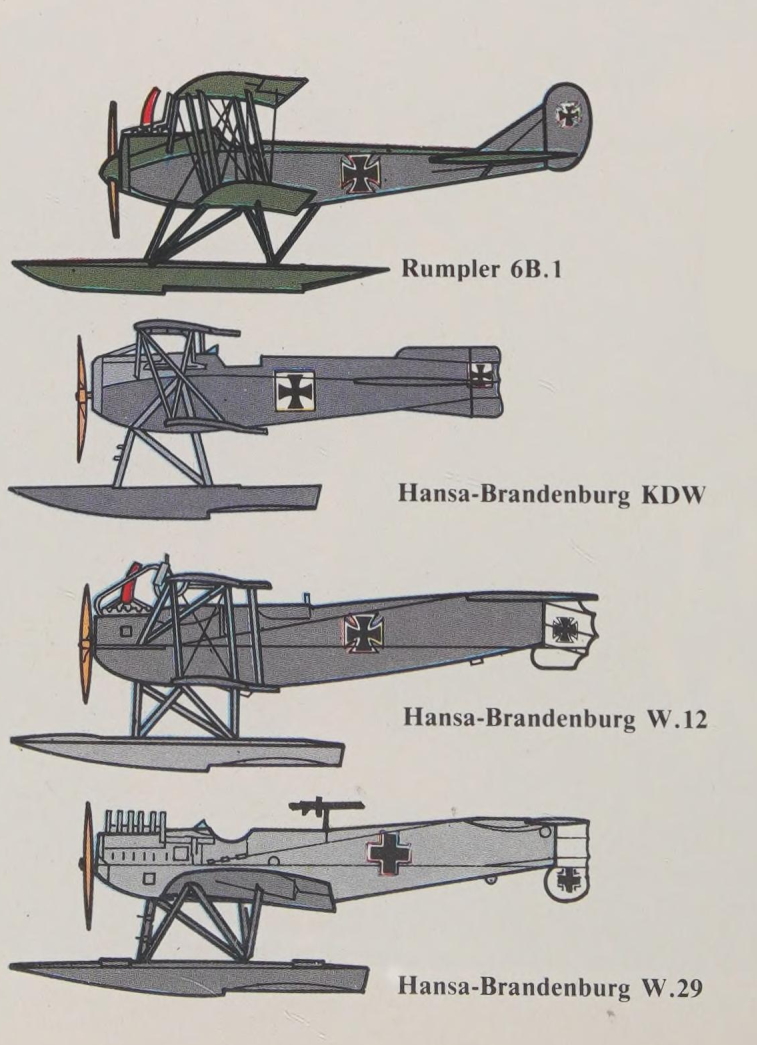

Naval aircraft were concentrated in 1.Marine Flieger Abteilung at Kiel- Holtenau, 2.Marine Flieger Abteilung at Wilhelmshaven and the Marine- Freiwilligen Fliegerkorps in Berlin-Johannisthal. During September 1915 the former two units were renamed Seeflieger Abteilungen, reporting directly to Befehlshaber der Marine Luftfahrt Abteilungen (BdL, Commander Naval Air Units), Konteradmiral Otto Philip. Large numbers of seaplanes were ordered, the Hansa Brandenburg KDW being introduced in 1916 as a single-seat seaplane fighting scout alongside forty Rumpler 6 B1s, and 114 Albatros W 4s were built beginning in 1917. Additionally, naval units had begun to field land-based aircraft, initially to protect U-boat bases and other naval installations on the Western Front, and on 21 December Oblt.z.S. Egon von Skrbensky arrived at Mariakerke (Ghent) with 113 officers and men to create the 1.Marine Landflieger Abteilung (Naval Land Aircraft Unit). Since the Navy had no facilities of its own for training single-seat pilots, when Fokker E monoplanes were introduced into naval landplane units naval pilots were sent to the single-seater school attached to Kampfeinsitzerstaffell (Kest I) on Sonthofen aerodrome near Mannheim, the first pilot to undertake this conversion course, Flugmaat Boedicker, being attached to 2.Marine- Feldflieger-Abteilung at Neumunster.

The basic unit of the Imperial German Naval Air Force was the Seeflugstation (Seaplane Station) or Landflugstation (Landplane Station). By mid-September 1916 there were some forty single-seat land fighters operating with the Marine Flieger Abteilungen, most of them Fokker E monoplanes. While a number of these were concentrated in Nieuwmunster for defending conquered Belgian territory, at least half of the fighter strength was deployed defending airship bases from Allied air attack. As the service grew during the war, a number of semiautonomous Staffeln (flights) were created; the Marinefeldjagdstaffel (Naval Fighter Squadron) commanded by Lt.z.S. Sachsenberg, operating with success in the area of the Fourth German Army occupied by the German Marine Corps. As air-to-air fighting activity increased, the Staffel was joined by other naval landplane fighter units until, towards the end of 1918, the five Marinefeldjagdstaffeln were formed into the Marinefeldjagdgeschwader under Sachsenberg’s command, with a strength of over fifty fighters. This was achieved despite aircraft production and allocation being held firmly under Army control, rendering naval fliers the junior partners in aviation matters. However, the success of the naval aviators was undeniable. During 1917-1918 they sank in the North Sea four merchant vessels, four patrol boats, three submarines, twelve other ships and a Russian destroyer. They had also managed to gain aerial superiority over the North Sea, shooting down 270 Allied aircraft for a loss of 170 of their own.

Two other major developments in German naval aviation took place in 1917. Firstly, the order to create three Küstenflieger Abteilungen in September for the patrol of coastal waters and assistance in coastal artillery spotting against enemy warships, and, secondly, the establishment that same month of the 1.Torpedostaffel, flying Hansa Brandenburg GWs, Friedrichshafen FF 41As and Gotha WD 11s in Germany’s first torpedo plane squadron.

Bombing had also been pursued by the German Navy. The landbased Riesenflugzeug (literally ‘Giant Aircraft’; a large bomber possessing at least three engines) was evaluated as a possible addition to the naval airship for bombing and long-range scouting purposes. However, experience with the Staaken VGO 1/RML 1 (Reichs Marine Landflugzeug 1) was plagued by difficulties. Engine troubles and structural failures of undercarriage assemblies had eventually been overcome, and the aircraft participated in some bombing operations on the Eastern Front, until, during a fully-loaded night take-off late in August 1916, a double engine failure resulted in a crash into a Russian forest. The machine was completely rebuilt and modified to take an additional two engines. At this time a transparent Cellon covering intended to render aircraft partially invisible and reduce searchlight illumination was under consideration, and the fuselage and tail unit were covered with this material. On the first test flight, at Staaken aerodrome near Berlin on 10 March 1917, engine failure resulted in the aircraft yawing wildly, and this was compounded by a control system malfunction. The pilots were unable to prevent the machine from crashing into the corner of one of the airship sheds.

Shipboard aviation had also begun in earnest almost immediately after the outbreak of war, largely due to Heinrich’s command of the Baltic Sea Fleet. The British freighter SS Craigronald had been seized as a prize while moored in Danzig at the outbreak of war and renamed Glyndwr, and the 2,425-ton ship was immediately impressed into service as an aircraft mother ship. Although no hangars were built on board, four seaplanes could be carried on the fore and aft decks. A heavy cargo crane was used to load and unload the aircraft, and the vessel was initially used as a training ship in the Bay of Danzig for the fledgling naval aircraft service. Two German cargo ships were also converted into bona fide seaplane tenders within the Baltic Sea; the SMH Answald and SMH Santa Elena, commissioned into the High Seas Fleet as Flugzeugschiff I and II respectively. Both received hangars fore and aft which could hold three and four aircraft each. Anti-aircraft guns were added, though the initial conversion proved unsatisfactory and they did not see action until 1915, following further modification. However, once in service they contributed greatly to the power of the German Baltic Fleet, keeping Russian naval forces on the defensive. The ex-British freighter SS Oswestry, which had been taken as prize in August 1914 and renamed Oswald, was also converted in 1918 to the role of aircraft tender and attached to IV Torpedo Boat Flotilla, carrying four FF 29s.

Additionally, the cruiser SMS Friedrich Carl had been provided with two aircraft in 1914, but was sunk by mines shortly thereafter and the aircraft were operationally unused. On 15 January 1915 an FF 29 became the first aeroplane to be launched from a submarine, the U12. The unarmed scout aircraft was lashed to the U-boat’s forward deck and piloted by the Zeebrugge naval airbase commander Oblt.z.S. von Arnauld de la Perrière. The U-boat’s bow was submerged after releasing the aircraft’s ties, and de la Perrière successfully took flight. However, Imperial Navy observers were unimpressed, and the decision was made not to use U-boats as aircraft carriers thereafter. Elsewhere, the battlecruiser Derfflinger, light cruiser Medusa and several Sperrbrecher made effective use of embarked aircraft, as did the armed merchant cruiser SMS Wolf.

When SMS Wolf left Kiel on 30 November 1916 on a 15-month voyage, during which she traversed three oceans as a commerce raider. She carried a Friedrichshafen FF 33E seaplane on board for scouting purposes. Named Wölfchen, the seaplane played an important part in Wolf’s marauding activities and carried out over fifty flights in this role. During the voyage Wölfchen was operated without the display of any national insignia other than the German War Ensign, which was flown from the innermost starboard rear interplane strut as occasion demanded. Crewed by Lt.z.S. Stein and Oberflugmeister Fabeck, the seaplane contributed to the Wolf sinking or capturing twenty-eight Allied vessels and returning home laden with booty from her victims.

Within the North Sea, German naval command finally came to understand the value of shipborne aircraft and ordered the construction of seaplane tenders capable of matching the speed of the Grand Fleet, something that mercantile conversion could not achieve. Two cruisers were ordered to be adapted, the SMS Roon and Stuttgart, and work began on Stuttgart on 21 January 1918 at the Imperial Dockyard in Wilhelmshaven. On 16 May she was commissioned as an ‘aircraft carrier’. Two large hangars had been installed aft of the funnels, with space for two seaplanes; a third was carried atop of the hangars. Stuttgart provided air cover for minesweeping operations within the North Sea but was never used in the offensive mode employed by Prince Heinrich within the Baltic.

Though Stuttgart had finally provided an aircraft tender that could keep pace with the High Seas Fleet, her small payload of only three aircraft was unsatisfactory, and plans were drawn up on Heinrich’s insistence for the construction of a flight-deck-equipped ‘true’ aircraft carrier. The answer was found in the incomplete hull of 12,585-ton Italian turbine-powered steamer Ausonia, which had been under construction in Hamburg’s Blohm & Voss shipyard at the outbreak of war. Conversion plans were drawn up by Lt.z.S.dR Jürgen Reimpell of 1.Seeflieger Abteilung, his final design proposals being completed by 1918. The ship was to carry two 82m hangar decks for wheeled aircraft and a third 128m hangar deck for seaplanes, all mounted above the existing structural deck. The flight deck itself was 128.5m long and 18.7m wide, and the ship was designed to carry either thirteen fixed-wing or nineteen folding-wing seaplanes, along with a maximum of ten wheeled aircraft. Ausonia could carry up to ten fighter aircraft and a combination of fifteen to twenty bombers and torpedo-floatplanes, but she was never completed. With the emphasis placed on U-boat construction, the final building drive of the Imperial Navy was never to reach fruition, as the war ended in November 1918, with Bolshevik revolution within the Kaiser’s Navy.

Of 2,138 naval aircraft fielded between 1914 and 1918, 1,166 were lost. The years of war yielded many ‘aces’ within the Marine Flieger Abteilungen, including three winners of the coveted Pour le Mérite: Theo Osterkamp with thirty-two victories, Gotthard Sachsenberg with thirty-one and Friedrich Christiansen with thirteen. However, the armistice did not see the end of their fighting as Sachsenberg was approached in January 1919 by General von der Goltz while demobilising the Marinegeschwader with a request to form a volunteer air unit that could serve in support of the ‘Iron Division’, composed of Freikorps troops and the remnants of the German 8th Army in the Baltics. Within weeks, Sachsenberg had recruited many former colleagues and formed Kampfgeschwader Sachsenberg, officially designated Fliegerabteilung Ost. Sachsenberg’s unit was despatched by German Defence Secretary Gustav Noske to join the fighting against Russian Bolshevik forces encroaching on German interests within the Baltic states. The Inter-Allied Commission of Control had insisted in the armistice agreement that German troops remain in the Baltic countries to prevent the region from being reoccupied by the Red Army, though the true motivation of the Iron Division was deeply rooted in the desire to install pro-German leadership within the region and possibly instigate the fall of the Bolshevik government of Russia, returning the monarchy to power. Sachsenberg’s approximately 700 personnel were based at Riga, Latvia, and gave aerial support to Freikorps units fighting ‘Reds’ on the Baltic borders of Germany, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia and Finland. Sachsenberg managed to amass a considerable number of aircraft before the Versailles Treaty of 28 June 1919 banned German military aircraft production. They established local air superiority and were mainly used thereafter for reconnaissance and ground-attack missions in support of Freikorps operations. However, after fierce fighting against Estonian troops and Latvian nationalists who had turned against the Germans following several reported massacres, the Iron Brigade was forced to retreat. Increasing international pressure from countries concerned about German expansion in the Baltic region finally prompted Reich President Friedrich Ebert to issue an order to end all official military operations. Volunteer units began to withdraw from the Baltic states during September 1919, and by December Kampfgeschwader Sachsenberg had returned to the East Prussian town of Seerappen and disbanded, its aircraft being recycled.

Under the terms of the Versailles Treaty, German air forces were banned, although the German Navy had been allowed to retain a small number of aircraft for mine clearance work:

ARTICLE 198.

The armed forces of Germany must not include any military or naval air forces.

Germany may, during a period not extending beyond October 1, 1919, maintain a maximum number of one hundred seaplanes or flying boats, which shall be exclusively employed in searching for submarine mines, shall be furnished with the necessary equipment for this purpose, and shall in no case carry arms, munitions or bombs of any nature whatever.

In addition to the engines installed in the seaplanes or flying boats above mentioned, one spare engine may be provided for each engine of each of these craft.

No dirigible shall be kept.

ARTICLE 199.

Within two months from the coming into force of the present Treaty the personnel of air forces on the rolls of the German land and sea forces shall be demobilised. Up to October 1, 1919, however, Germany may keep and maintain a total number of one thousand men, including officers, for the whole of the cadres and personnel, flying and non-flying, of all formations and establishments.

Based at Nordeney and Holtenau, the aircraft provided great assistance for the hard-pressed minesweeping ships. By October 1919, 11,487 fixed and 12,386 drifting mines had either been swept or destroyed. Within two months all of the minesweeping aircraft were then scheduled to have been handed over to Allied authorities for disposal, but Kaptlt. Walther Faber, a former combat pilot with the Marine Flieger Abteilung and later Adjutant and Training Advisor to the Naval Air Service Chief of Staff (Adjutant und Referent Chef des Stabes Marineluftfahrt) from August 1917, managed to retain six operational machines within the Baltic well into the 1930s, despite the naval air service having been officially dissolved during 1920.