In the days after the Sydney raid, the Australian Department of Information monitored Japanese broadcasts around the clock, but picked up no public broadcast relating to the Sydney attack until 5 June.

The Imperial Navy made an attack on Sydney Harbour with midget submarines on 31 May. We have succeeded in entering the harbour and sinking one warship. The three midget submarines which took part in this operation have not reported back.

Although MacArthur’s headquarters issued a brief statement on 1 June, the first detailed reports of the raid came from American and British broadcasts. The Sydney press was particularly outraged when the initial news came from Melbourne, not Sydney. When the Minister for the Navy came under fierce fire in the House of Representatives for not allowing Sydney to release the news, Mr Makin replied: “It was thought undesirable to make an earlier announcement because enemy ships might still have been in the vicinity.”

In response to the Japanese raid on Sydney, the Deputy Prime Minister, Francis Forde, made the following speech in Parliament:

The public should not complacently count on this as the last attack in these waters. The attempted raid brings the war much nearer to the industrial heart of Australia. It should clearly indicate the absolute necessity for eternal vigilance by all services. It should act as a new stimulus to the whole of the people to co-operate wholeheartedly on a complete war effort.

Forde’s words were both true and prophetic. On 3 June, Sasaki brought I-21 to the surface 40 miles off Sydney and attacked the Australian steamer Age with gunfire. Unarmed, the steamer ran for safety and arrived in Newcastle the following day without further incident.

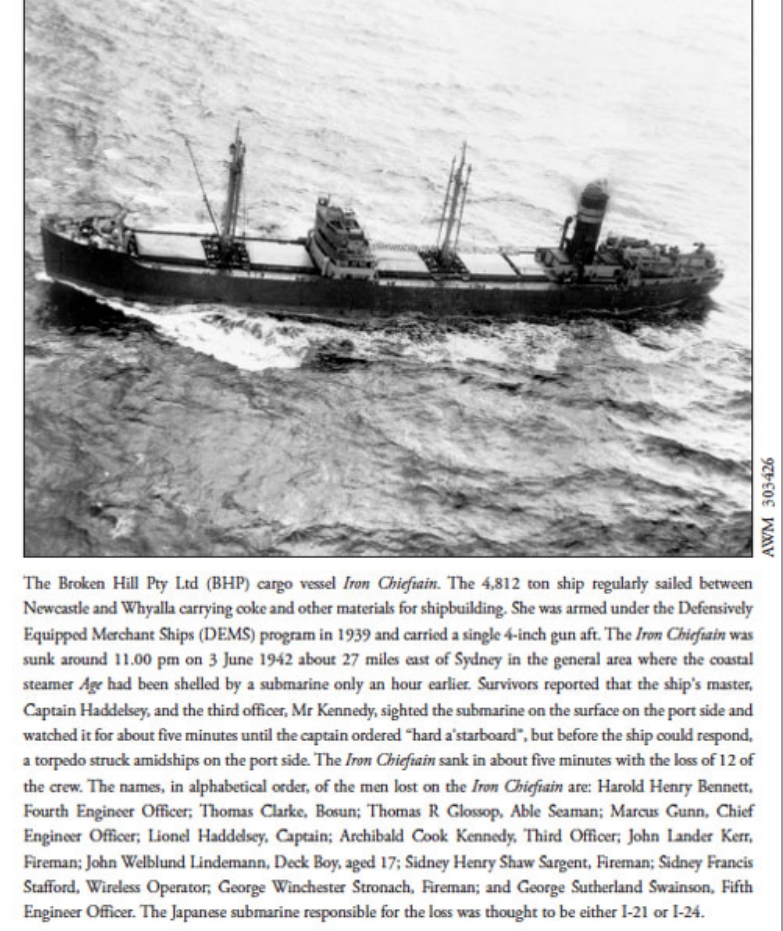

At 11:30 pm, soon after the Age was attacked, I-24 sank the Australian coaster, Iron Chieftain, which was on passage from Newcastle to Whyalla. Iron Chieftain had sailed from Newcastle at 10:00 pm but was only able to make good six knots against the heavy seas. Twenty seven miles from Newcastle Harbour, the submarine surfaced and fired a torpedo at the coaster. Laden with coke, Iron Chieftain sank in five minutes, taking with her 12 crew including the master and third mate who were last seen on the bridge.

One of the survivors, Naval gunner Cyril Sheraton, gave the following account of the Iron Chieftan attack in the Sydney Morning Herald:

I was in my pyjamas and watch coat beside my gun when the torpedo struck. I tried to get my gun into action but did not have a chance. The captain and third mate were on the bridge and were watching the submarine for five or six minutes before the skipper shouted “Hard a’starboard”. The torpedo struck before the ship could swing. I could see the submarine 200 yards away on the port side. As the ship sank under me, I was dragged onto a raft. After the ship sank, the submarine circled our raft and we thought that we might be machine-gunned so we laid still. The submarine finally left and we drifted in the darkness.

When news of the Iron Chieftain’s sinking reached Sydney, Rear-Admiral Muirhead-Gould closed the ports of Sydney and Newcastle to outward bound shipping, and ships at sea were warned to “zigzag”. The anti-submarine vessel Bingera sailed from Sydney to search for survivors and picked up some of the crew, including Sheraton. Another 25 crewmen were found 30 hours later after rowing their open boat ashore.

With Second Officer Brady in charge, the lifeboat picked up as many men as could be seen in the water. When no more survivors could be found, they began to row through the heavy swell, taking turns at the oars to keep warm. After some hours the sea abated and conditions became easier. The men began singing to boost their morale, but it was a dismal attempt and ceased after a while. They continued to row in silence. Thirty hours later they arrived about a mile off The Entrance, north of Sydney. Unfamiliar with the area, Brady fired distress flares into the sky, but local fishermen did not understand their meaning. When help failed to arrive, the men rowed slowly ashore, weary, drenched and cold. The exhausted Second Officer was reluctant to surrender his charge to the police and had to be threatened with violence before he would consent to go to bed and warm up.

At dawn on 4 June, six hours after Iron Chieftain was sunk, I-27, en route to Tasmanian waters, surfaced and attacked the Australian steamer Barwon 30 miles off Gabo Island. The submarine commenced the attack with gunfire, followed by a torpedo, which exploded prematurely alongside the steamer. Fragments of metal landed on the ship but there was no damage or casualties. Barwon was able to escape by outrunning her attacker.

At 4:45 pm on the same day, I-27 torpedoed the Australian ship Iron Crown, laden with manganese ore and bound for Newcastle. Iron Crown went down in one minute, taking with her 37 crew, including the captain. The submarine was forced to crash dive when an Australian Hudson aircraft suddenly appeared over the horizon.

Australian naval authorities became exceedingly jittery about the increasing Japanese submarine activity and frequent molesting of Allied shipping. On 4 June the Australian Naval Board decided to suspend all merchant sailings from eastern and southern Australian ports. However, merchant vessels already at sea before the Naval Board directive continued to fall victim to elements of the Third Submarine Company. In the absence of enemy warships, the Japanese naval authorities considered merchant vessels legitimate targets.

It was the Japanese Navy’s policy to limit the number of torpedoes that a submarine commander could fire at a particular target. Merchant ships and destroyers were allotted only one torpedo, cruisers warranted three, and battleships and aircraft carriers were allotted maximum torpedo firepower. Since this policy reduced the chances of sinking a merchant ship, Captain Sasaki ordered his submarine force to resort to surface gunfire attacks in an effort to economise on torpedoes.

While Sasaki’s submarine force waged its campaign of destruction, Allied aircraft continued to scour the sea in search of the submarine raiders. During this period there were many reported sightings of periscopes. However, to confuse the enemy, Sasaki’s force released decoy periscopes along Australia’s east coast. These decoys were made of long bamboo sticks, painted black, at the top of which were attached mirrors that would glint in the sunlight. Below the surface were two sake bottles lashed to the decoy periscope. The glass bottles were half-filled with sand and half-filled with diesel oil. The weight of the sand would cause the bamboo stick to float upright in the water, and the oil was to convince the enemy of a successful attack when it floated to the surface once the bottles shattered following a bomb or depth charge attack.

One of these decoy periscopes was responsible for a reported sighting by a Dutch aircraft eight miles south-east of Sydney on the morning of 6 June. The aircraft attacked and reported damaging a submarine at periscope depth after thick diesel oil was seen on the surface.

A decoy periscope was later recovered offshore by a commercial fisherman who turned it over to Muirhead-Gould’s staff for examination.

Also on 6 June, 22-year-old Flight Lieutenant G. J. Hitchcock taxied his Lockheed Hudson bomber across the tarmac at Williamtown, north of Newcastle, and, with only a scratch crew, took off to search for enemy submarines. The base medical officer had been invited to join the flight with the promise that Hitchcock would sink a submarine. Hitchcock’s promise almost became a reality.

Flying at 2,000 feet, the air gunner, Flight Sergeant A. T. Morton, sighted a periscope 80 miles east of Sydney. Hitchcock descended abruptly to 500 feet and commenced his attack. The Hudson accidentally dropped its entire bomb load, which fell astern of the periscope. Hitchcock recalled that the aircraft received an almighty thump from behind when the bombs exploded. The Hudson circled the area for half an hour. While bubbles were seen rising to the surface, there was no oil. Hitchcock considered his attack was unsuccessful, but newspaper accounts thought otherwise, crediting the Hudson with “the first Australian killing”. Hitchcock told the author that the newspaper accounts had the effect of lifting morale and he and his crew became temporarily famous.

In the days that followed the Sydney Harbour attack, residents had begun to settle back into their normal daily routines. However, they were not without foreboding as they read press reports of submarine attacks on merchant shipping along the coast.

Sydney’s apprehensive mood turned to panic when Sasaki’s submarine force interrupted their campaign against Allied shipping and turned their attention to frightening the civil population. On 8 June, shortly after midnight, I-24 surfaced 12 miles off the coast of Sydney and fired 10 high explosive shells.

The examination vessel HMAS Adele, which was responsible for challenging suspicious vessels attempting to enter harbour, sighted the gunfire flashes out to sea, as did the Outer South Head army battery, which probed the sea with searchlights. Five minutes later the air raid alarm was sounded and city and coastal navigation lights were temporarily extinguished. The submarine submerged before the coastal defences could return fire.

There were no major casualties reported from this unexpected shelling, although one resident – a refugee from Nazi Germany – was terrified when a shell crashed though his bedroom wall. According to newspaper accounts, the man leapt out of bed, fracturing his ankle, and the shell failed to explode.

The remaining shells exploded in the suburbs of Rose Bay and Bellevue Hill, shattering windows and causing only superficial damage. One shell exploded harmlessly in Manion Avenue, Rose Bay, where a large crater was formed in the roadway.

The main objective of the shellfire was to destroy the Sydney Harbour Bridge, however, the Japanese also wanted to frighten the population. Although they failed in their first objective, they succeeded in the second beyond their expectations.

During the shelling, panic broke out when confused residents ran screaming into the streets thinking the air raid siren meant that Sydney was under attack by enemy aircraft. Urban Australians did not react very favourably when, later that morning, harbour front and other wealthy Eastern Suburb residents put their houses up for sale and fled to the Blue Mountains and even further inland, fearing a Japanese invasion at any moment.

A steady trickle of harbourside residents had been leaving Sydney following the Japanese attack on Sydney Harbour more than a week earlier; but with the shelling of the Eastern Suburbs, the trickle increased to a frenzied stream of panicky citizens. When every house, boarding house and hotel in the Blue Mountains was crammed, these “escapees” retreated further inland to Orange in the central-west of New South Wales. Some people fled from Sydney to the Hunter Valley – to towns like Singleton and Muswellbroook – but they were turned away when every available accommodation space had been taken. This is a good indication of how serious the belief was that Australia would be invaded by the “Yellow Peril”.

Compared with Londoners during the Blitz, these Australians behaved with less than Churchillian courage. Only after the war was over did many of them sheepishly return, some buying back their houses at vastly inflated prices.

Scenting an opportunity, poverty-stricken European refugees, many of them Jewish émigrés who had weathered far greater ordeals in Europe, quickly moved into the area. They shrewdly bought up the vacated real-estate at absurdly deflated prices and, after the war, many became millionaires overnight. One Eastern Suburbs real estate agent, Mr Karl Malouf, told the author that the exodus of the rich had been extensive. He remembers the harbourside suburbs of Vaucluse and Bellevue Hill were a forest of “For Sale signs.” Malouf‘s company went on to become one of Sydney’s best known realtors.

Just over two hours after I-24 shelled Sydney, I-21 surfaced three miles off Newcastle. The submarine fired 20 star shells over the industrial heart of the city, followed by six high explosive shells, only three of which exploded. Close examination of the unexploded shells later that day revealed that they had been manufactured in England in 1914! The nose sections were very rough, with some fuses bent and damaged, which explained why the majority of shells failed to explode.

The main Japanese target at Newcastle was the BHP steelworks. As with Sydney, however, the shells landed over a wide area, one shell exploding on the road behind Fort Scratchley, a coastal Army battery, and another some distance away near Nobby’s Head. Two star shells also exploded above the corvette Whyalla, which had recently arrived in Newcastle after searching for enemy submarines off the coast.

Fort Scratchley, overlooking Newcastle Harbour, was originally built during the Russian scare of the nineteenth century and was modified and reactivated for World War II. In the early hours of the morning, the duty sergeant at the Fort reported to the searchlight commander, Captain W. J. Harvey, that he could see flares in the sky and that something unusual appeared to be happening. Gun flashes were then seen and the searchlights probed the sea. At the extreme range of the searchlights, Gunner Colin Curie reported sighting a submarine. The battery commander, Captain Walter Watson, put the battery on alert and the guns were loaded ready to fire. Suddenly, Watson saw a gun flash and cried “Duck!” The shell exploded in Parnell Place, narrowly missing the observation post. Watson telephoned fire command for permission to open fire and, when he received no reply, opened fire anyway. The telephonist then reported, “Fire command says engage when ready, Sir!” Watson retorted, “Tell them I bloody-well have!” He then gave ranging corrections to his gunners and fired a second salvo.

The pilot steamer Birubi was at sea off Nobby’s Head when the shelling began. In her haste to run for the harbour entrance and safety, the pilot vessel emitted huge clouds of thick black smoke, which obscured Watson’s field of vision and he was unable to correct the range of fire. Sasaki submerged before Fort Scratchley could fire a third salvo. The pilot vessel later reported that the first salvo had fallen short of the submarine and the second had overshot.

Some remarkable escapes were made from the Newcastle shelling. Residents had heard an air raid siren shortly after midnight, followed by the “All Clear”, which actually signified the end of the shelling attack on Sydney. When, an hour later, firing commenced on Newcastle, residents were confused and caught unaware.

In Parnell Place, Mrs Wilson had decided to evacuate her two young children from their home above a shop: “I thought it was only air raid drill or practice. Then I realised it wasn’t… The shells were screaming across. The worst part was not knowing where they were going to hit.”

Scooping her two children from their bed, Mrs Wilson was making her way downstairs when a shell exploded on the road outside. It was not until daylight that the young mother realised how close she and her children had come to death. She discovered shrapnel from the blast had torn through a wire mattress base where the children had been sleeping and, when she rolled back the mattress, a huge, gaping hole was revealed in the wall.

There were only two casualties reported from the Newcastle shelling, both victims of shrapnel from the blast in Parnell Place. Bombardier Stan Newton had been on his way to Fort Scratchley when he was knocked unconscious by a piece of shrapnel that struck him in the forehead. Regaining consciousness, he was greeted by a surprised air raid warden. Newton then ran on to the Fort to take up his position, unaware the shrapnel was still lodged in his head.

Meanwhile, naval authorities ordered a total blackout of the Newcastle and Sydney coastal areas. HMAS Whyalla and the American destroyer Perkins were ordered to escort eight merchant ships from Newcastle to Melbourne.

Submarine bombardment of enemy cities was employed by the Japanese only on limited occasions. From the time of surfacing, often over a minute passed before the submarines could commence firing. Ranges had to be estimated from charts, and to score a direct hit was extremely difficult. The rangefinders they used were portable and inaccurate, making the whole operation a rather clumsy exercise. Also, only 20 shells could be stored at one time in the ammunition locker on the upper deck. If more ammunition was required, it had to be brought up from below, thus creating a dangerous situation, especially if the submarine had to submerge in a hurry.

After the shelling of Sydney and Newcastle, I-24 and I-21 turned their attention back to terrorising merchant ships off the coast. At 1:00 am on 9 June, I-24 pursued and shelled the British merchant ship Orestes 90 miles south of Sydney. Steaming independently from Sydney to Melbourne, Orestes presented a prime target for I-24, which chased the merchantman for five hours. During the running battle, Orestes suffered several direct hits, resulting in a large fire. Believing the merchant vessel was doomed, I-24 broke off the attack; but Orestes succeeded in extinguishing the fire and made Melbourne safely the next day.

Not so fortunate was the Panamanian vessel Guatemala. At 1:15 am on 12 June, I-24 intercepted and successfully sank the merchant ship 40 miles from Sydney. Guatemala had left Newcastle in the convoy escorted by Perkins and Whyalla, but soon found herself straggling behind the convoy. The Norwegian master, Captain A. G. Bang, heard two gunshots to starboard but saw nothing. A few minutes later, the second officer saw the track of a torpedo, which struck the ship before he could take evasive action. The crews took to the lifeboats and Guatemala sank an hour later without any casualties. Soon afterwards the Australian minesweeper Doomba picked up the 51 crew and transported them to Sydney.

The Japanese account of the Guatemala’s sinking varies slightly from official Australian records. In his book, Sunk, Mochitsura Hasimoto records the submarine fired one torpedo at Guatemala, which detonated prematurely. The submarine then surfaced and engaged the Panamanian vessel with gunfire, but found it difficult to score a direct hit in the darkness. The submarine intercepted an SOS from the ship announcing she was under attack and asking for assistance. Eventually, one of I-24’s shells hit its target, after which Guatemala’s crew stopped the ship and took to the lifeboats. The submarine then fired a second torpedo, which sank the doomed ship.

This was the last enemy submarine attack in Australian waters for about six weeks.

From the time of the Sydney Harbour raid until the sinking of Guatemala, the Third Submarine Company had sunk four ships with the loss of 73 lives over a period of 12 days. From mid-July until the beginning of August, three more large Japanese submarines – I-11, I-174 and I-175 – joined with I-24 to continue Japan’s campaign of destruction along the coast. They succeeded in sinking another four vessels before leaving Australian waters.

Thereafter, a period of calm followed until January 1943 when I-21 returned to Australian waters and sank six ships off Sydney over the following month. Then, in April 1943, I-26 sank two vessels off Brisbane, and a further six ships were sunk between April and mid-June 1943.

When Japan lost her forward bases at Rabaul and Truk, distant operations into Australian waters were rendered progressively more difficult. By the end of July 1943, submarine operations became almost impossible.

Between June 1942 and December 1944, a total of 27 merchant ships were sunk in Australian waters with the loss of 577 lives, including the 21 sailors who lost their lives on Kuttabul. Of the total fatalities, 268 lives were lost in one attack when the Australian hospital ship, Centaur, was sunk 40 miles east of Brisbane on 14 May 1943. The Centaur sank in about three minutes with only 64 survivors, who spent 36 hours in the water before rescue. The Japanese submarine thought responsible for the sinking was 1-177 commanded by Lieutenant-Commander Nakagawa, who was later tried as a war criminal and spent four years in prison for firing on survivors from a British merchant vessel torpedoed in the Indian Ocean. The sinking of Centaur was not raised at his trial.