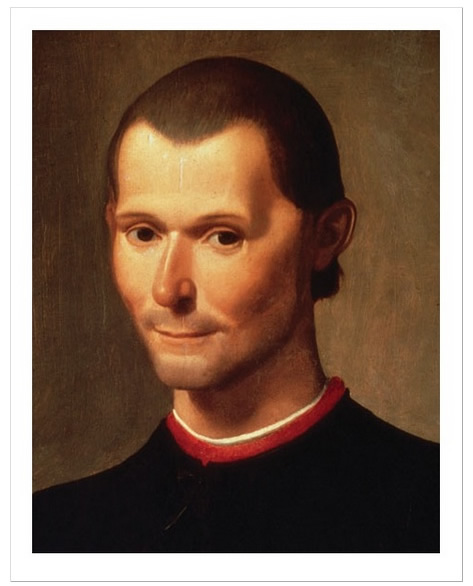

Machiavellian is a word often used in context with Walsingham and it is believed he came into contact with the Italian’s writings while in Italy. The Florentine Niccolò Machiavelli was responsible for a number of important works, including the notorious Il Principe (The Prince), which was partly based on the exploits of Cesare Borgia, the illegitimate son of Pope Alexander VI. Similar in nature to Kautilya’s manual on statecraft, Il Principe also drew on the experiences of historical figures, in particular those recorded by the Roman historian Livy. By way of an example, a typical piece of ‘Machiavellian’ advice is found in Chapter 18 of Il Principe: ‘… men are so simple, and yeeld so much to the present necessities, that he who hath a mind to deceive, shall alwaies find another that will be deceivd.’

Under the heading of the ‘Secrete conveing of letters’ Machiavelli discusses the diverse means of communication used by those under siege. He introduces the reader to the world of cipher writing, explaining messages were not sent ‘by mouth’. As a further precaution, the enciphered messages were hidden in a variety of ways: within the scabbard of a sword, or placed in an unbaked loaf, which was then cooked and given to the messenger. Some spies were known to hide messages ‘in the most secret place of their bodies’ while others hid them in the collar of a pet dog. Machiavelli also revealed how others disguised their secret messages by use of secret ink, writing in between the lines of an ordinary letter. This way the sender did not have to trust the carrier with their secrets.

In Renaissance Italy cryptography became an everyday tool of machinating diplomats. In turn, intercepted ciphers required experts to crack them. Foremost among these was Giovanni Soro, cipher breaker-in-chief to Venice from 1506. Even the Vatican would send him messages to test their impenetrability. While in Italy Walsingham picked up what was considered the manual on code breaking by Leon Battista Alberti, the inventor of the cipher disk. Alberti’s main contribution to the world of secret codes was to switch between two cipher alphabets in the same message in order to baffle attempts at frequency analysis.

Other advances in cryptography that Walsingham would have been aware of included the insertion of blanks into numeric ciphers. In this case each letter of the alphabet could be issued a value – for instance ‘A’ might become ‘23’, while ‘86’ might represent ‘B’ and so on. To confuse frequency analysts, other numbers would be inserted that had no value whatsoever. Some numbers would indicate that the letter preceding it should be repeated – an ingeniously simple way of avoiding writing the same letter twice in a row. As the ciphers became more sophisticated, some numbers or symbols were a shorthand code for key words or names. In this case ‘43’ might indicate a commonly used word such as ‘the’ while the number ‘76’ could mean ‘the Queen’ or a place name, like ‘Rome’ for instance. The variations were endless – but not impregnable.

Although his stay in Padua must have been a great influence on the future spymaster, he did not remain there long. At the time he was being made consularius, the ‘Dudley Plot’ to depose Bloody Mary failed. As a Protestant, Walsingham got out of Italy, spending much of his time in Switzerland. His self-imposed exile continued until Queen Mary died. Returning to England Walsingham came under the patronage of William Cecil, later Lord Burghley (1521–98), who had been responsible for all matters of secret intelligence. However, as he went on to lead Elizabeth’s government, Burghley began farming out much of the intelligence work to Walsingham.

After a period as ambassador to France, Walsingham became Elizabeth’s Secretary of State, a post he would retain until his death in 1590. As Secretary of State, Walsingham’s prime concern and his major achievement was quite simply keeping Elizabeth alive.

There had already been several attempts to replace Elizabeth with Mary Queen of Scots. The Ridolfi Plot of 1571, involving Philip II of Spain and Pope Pius V, led to the execution of the Duke of Norfolk in June 1572. Then in 1583, Walsingham’s agents had arrested Francis Throckmorton, who, under torture, revealed a Catholic conspiracy to place Mary Queen of Scots on the throne. On both occasions, Parliament had called for Mary to be executed, but Elizabeth had overruled them. Walsingham agreed with the parliamentarian view that the only way to stop Catholic plots against Elizabeth was to get rid of Mary. The trouble was in convincing Elizabeth to recognize this and getting her to act. Although Mary was under effective house arrest from 1568, Elizabeth did not want blood on her hands. What Walsingham needed was implicit proof that Mary was involved in a plot to kill Elizabeth.

Such an opportunity presented itself in December 1585, when a Catholic named Gilbert Gifford arrived at the port of Rye. It is unclear if he was acting from conscience, avarice or fear, but Gifford went to Walsingham and revealed he was acting as a messenger between Mary and her supporters on the Continent. He offered to work as a double agent and demonstrated all the right credentials, telling Walsingham: ‘I have heard of the work you do and I want to serve you. I have no scruples and no fear of danger. Whatever you order me to do I will accomplish.’ Walsingham sent Gifford to his code-breaking expert, Thomas Phelippes, who took hold of the secret correspondence and set to work deciphering it.

Walsingham’s plan was quite simple. Gifford was sent to the French ambassador, Baron de Châteauneuf, to reveal a means of delivering messages to Mary in secret. He had bribed a sympathetic brewer who would conceal letters in beer barrels being delivered to Chartley, where Mary was being held. Because of his time on the Continent and the contacts he had made there, Gifford was able to convince Châteauneuf he could be trusted. However, before Châteauneuf’s messages were delivered to Mary, Phelippes saw them first. After he copied them, another of Walsingham’s men, Arthur Gregory, expertly resealed the envelopes with counterfeit wax seals. They were then taken to the brewer who had them put in a watertight bag and inserted into the bung of the beer barrel. Mary’s replies followed in reverse. When Phelippes quickly broke Mary’s cipher, Walsingham was privy to her secrets. All he needed was a conspiracy to pounce on.

There were plenty of English Catholics who were unhappy, but to find one actually prepared to murder the queen was another thing entirely. Fortune must have been smiling on Walsingham then, for in March 1586 at the Plough Inn, London, a plot was formed, led by the outlaw priest John Ballard (or to use his alias – ‘Captain Fortesque’, gentleman soldier) and Anthony Babington, an impulsive 24-year-old law student at Lincoln’s Inn. With Ballard was his companion, Bernard Maude, who had obtained passports for them to travel to Paris. There in the French capital they planned to meet Mary’s supporters and the Spanish ambassador, Don Bernardino de Mendoza. The first item on their agenda was the Catholic invasion of England. Poor Ballard had no idea his dependable Maude was an English government spy.

Towards the end of May 1586, Ballard and Maude returned from France and excitedly told Babington the news. By September at the latest, a force of 60,000 French, Italian and Spanish troops would be landing in England. But before they could land, certain undertakings had to be fulfilled. Ballard said that he and Maude would travel to Scotland and raise a rebellion there, while Babington led an uprising of English Catholics. Thirdly, someone would have to assassinate Elizabeth – only then would the continental troops come ashore.

The person nominated for the regicide was John Savage, who while studying at Rheims had taken a vow to kill Elizabeth. From his time on the Continent Gilbert Gifford already knew of Savage’s vow. So, with the interception of Mary’s mail fully in swing, Gifford was sent to shadow Savage and incriminate him in the plot.

With Savage and Ballard under close surveillance by double agents, only Babington was still relatively unknown to Walsingham. The opportunity to place an agent with him arose in June when Babington tried to obtain a passport. There are several theories why Babington was planning a trip abroad at this juncture, even that the whole passport application was a red herring to throw Walsingham off his scent. The most plausible explanation is that his friend, Thomas Salusbury, realized that Ballard was nothing but trouble and was trying to get Babington as far away from the priest as possible. Their first attempt to secure a passport failed, but then Salusbury used a friend named Tindell to contact Robert Poley, a man reputed to have connections with Walsingham, who held ultimate sway over passport applications. In fact Poley was a fully fledged Walsingham stooge.

Poley heard Babington’s request for a passport and agreed to help, for a sum. Told by Walsingham to ingratiate himself with Babington, Poley offered to go abroad with Babington as a companion-servant. Babington appears to have been totally taken in by Poley, who by the end of June had arranged for Babington to meet Walsingham to discuss his passport request. During this, the first of three meetings, Walsingham appeared to be sounding Babington out to become an informer for him while abroad. This was all very normal – all loyal Englishmen travelling abroad were expected to pick up little snippets of intelligence in return for a passport. In truth Walsingham had no intention of letting Babington anywhere near the Continent. He either wanted Babington to turn Queen’s evidence, betray his fellow conspirators and implicate Mary, or be arrested as a conspirator himself.

A second meeting was held on 3 July at Walsingham’s house, when the spymaster pressed Babington over what sort of services he was prepared to perform in return for the passport, hoping he might inform on Jesuit missionaries. The meeting concluded with Walsingham convinced that Babington was of no use to him. Instead he would be set up as the fall guy. Gilbert Gifford had recently returned from a mission to Paris and Walsingham sent him to Babington to reveal the Catholic invasion was still very much on schedule. Gifford told Babington to communicate to Mary the details of what was being planned, using of course his ‘secure’ means of communication – the beer barrel express.

On 6 July Babington sent a letter that proved to be his death warrant. He named Ballard as the bringer of news from abroad, but no others. As for the details of the plot, Babington informed Mary that he with ten gentlemen and a hundred of their followers would come to rescue her. For the murder of Elizabeth – ‘the usurper’ he called her – he claimed to have six ‘noble gentlemen’ all of whom were his private friends. This of course was not strictly true, as Savage was the only one committed to the deed thus far. Most importantly, Babington asked for Mary’s approval and her recommendations concerning the arrangements he had made. If Mary said ‘yes’ to the plot, Walsingham’s elaborate snare would be sprung.

Mary’s reply came out of Chartley on the night of Sunday 17 July. She had already sent two letters in May that strongly incriminated her – one to the Spanish ambassador, Mendoza, giving her support to an invasion of England, and the other to a supporter, Charles Paget, asking him to remind Philip of Spain of the urgency for invasion. Both letters had reached Walsingham, but neither implicated her in the way the letter to Babington did. In it Mary wholeheartedly endorsed Babington’s plan and even gave advice on how best to proceed. When referring to the assassination of Elizabeth, Mary stressed the importance of her being quickly rescued lest her keeper learned of the plot and took measures to prevent her rescue.

After it was decoded by Phelippes, the letter was taken by Walsingham to Elizabeth. Not satisfied with it, Elizabeth asked that a postscript be added that might reveal the identity of the six would-be assassins. Walsingham had Phelippes copy out the whole message again, this time inserting the appropriate pieces.26 The postscript read:

I would be glad to know the names and quelityes of the sixe gentlemen which are to accomplish the dessignement, for that it may be I shall be able uppon knowledge of the parties to give you some further advise necessarye to be followed therein … as also from time to time particularlye how you proceede and as soon as you may for the same purpose who bee alredye and how farr every one privye hereunto.

On 29 July the letter finally arrived with Babington, who slowly began to decipher it. The following day, a message from Walsingham arrived requesting another meeting. The spy Robert Poley began hinting to Babington that he should tell Walsingham everything about the plot. Realizing that their plan to raise England and Scotland in rebellion was a fantasy, Babington, Savage and Ballard agreed that they should tell Walsingham everything, but try to shift all the blame onto Maude and Gifford. Poley was sent to arrange the meeting.

Walsingham, meanwhile, had been playing a waiting game. He wanted to see how Babington would reply to Mary’s letter, but he was beginning to fear the plotters might be about to flee. On 4 August he finally struck, arresting Ballard as he went to visit Babington.28 When Babington learned of Ballard’s capture he was at a complete loss and turned to Poley for advice. Babington asked if he should turn himself in and blame Ballard, or go on the run. Poley advised him to do neither, but to remain where he was. He would go and petition Walsingham for Ballard’s release.

When Poley did not return that evening, Babington wrote him a farewell note and prepared to flee. However, Walsingham had sent another agent, John Scudamore, to keep track of Babington. The two went to dinner together and towards the end of the meal a note arrived for Scudamore. A glimpse of the handwriting told Babington all he needed to know – the message was from Walsingham. Babington calmly stood up and, leaving his sword and cloak at the table, he went off to pay for the food. Once out of sight, he ran for his life.

Warned by Babington as he stopped to change clothes, the conspirators went their separate ways in order to avoid arrest. Babington held out in St John’s Wood with several companions. They reached a Catholic family by the name of Bellamy, where they received food and attempted to disguise themselves as labourers by cutting their hair and staining their skin. However, by 14 August they had been spotted and were arrested then returned to London. So pleased was Elizabeth, she ordered the church bells rung in celebration, with bonfires lit and psalms sung in thanksgiving.

Before being brought to trial on 13 September 1586 facing charges of high treason, the conspirators had the ordeal of interrogation to face. As a Catholic priest, Ballard could expect every device and means of torture to be placed at the hands of his tormentors. His interrogation began on 8 August and by the time of the trial he could no longer walk and had to be carried into the Westminster courtroom. One of the accused had died during the interrogation, or, to use the improbable official verdict, had strangled himself. All bore the marks of torture, but Babington and Savage were treated less harshly. In return Babington provided two long confessions, no doubt with Walsingham aiding his recollection of events. All must have been sickened to realize how they had been set up and played by Walsingham.

The trial was of course a mere formality. All were condemned to die and, as a deterrent against further plots, Elizabeth asked if some crueller than usual punishment might be devised for them. When Lord Burghley assured her that the existing methods were quite sufficient, he was making the understatement of the millennium. On 20 September Babington, Ballard, Savage and four others were tied face down onto hurdles at the Tower of London and dragged by horses through the streets of London to the place of execution. A disturbingly graphic, probably first-hand account of the execution was given by William Camden in his Annales:

The 20th of the same month, a gallous and a scaffold being set up for the purpose in St. Giles his fieldes where they were wont to meete, the first 7 were hanged thereon, cut downe, their privities cut off, bowelled alive and seeing, and quartered, not without some note of cruelty. Ballard the Arch-plotter of this treason craved pardon of God and of the Queene with a condition if he had sinned against her. Babington (who undauntedly beheld Ballard’s execution, while the rest turning away their faces, fell to prayers upon their knees) ingenuously acknowledged his offences; being taken downe from the gallous, and ready to bee cut up, hee cried aloud in Latin sundry times, Parce mihi Domine Iesu, that is, Spare me Lord Jesus. Savage brake the rope and fell downe from the gallous, and was presently seized on by the executioner, his privities cut off, and he bowelled alive. Barnwell extenuated his crime under colour of Religion and Conscience. Tichburne with all humility acknowledged his fault, and moved great pitty among the multitude towards him. As in like manner did Tilney, a man of a modest spirit and goodlie personage. Abbington, being a man of a turbulent spirit, cast forth threates and terrors of blood to be spilt ere long in England.

The carnage unleashed upon these seven men stretched the public’s desire for justice to the limit. Apparently, when the executioner plunged his hand into Babington’s body to pull out the heart, the plotter still appeared conscious and was seen to murmur, causing the crowd to gasp. So violent were their ends that the Queen ordered the other seven men be hanged until dead before the ritual disembowelling began. Their sentence was carried out the following day.

With incontrovertible proof and the confessions of the Babington plotters, Walsingham now turned to his real prize, the trial of Mary. Despite Walsingham’s proof, Elizabeth was still reluctant to take action against her. A trial was eventually held at Fotheringhay Castle on 14 October 1586. The prosecution began with a discourse on the Babington conspiracy, concluding that Mary ‘knew of it, approved it and had promised her assistance’. Mary began her defence courageously, denying she knew Babington, that she had never received any letters from him, nor written to him, nor plotted against the Queen. If there was written evidence in her own hand contrary to her statement, she demanded it be produced. She did admit some English Catholics were unhappy, but pointed out that shut up in her virtual prison, she could neither know nor hinder what was being attempted in her name.

The prosecution revealed Babington’s confession of a correspondence with Mary. When copies of Babington’s letters to Mary were read out, she admitted Babington may well have written them, but could the council prove she had received them? They could. Proof came when more of Babington’s confession was read out, in which he confessed that Mary had written back to him. Mary burst into tears, but claimed her cipher had been used by others to forge the letters – something which was partially true.

The confessions of Savage and Ballard were then read out. They had confessed that Babington had told them of certain letters he had received from the Queen of Scots. Mary continued with the line that it was easy to counterfeit ciphers. She then turned her guns on Walsingham, who found himself ‘taxed’ by her words. As a lawyer, he was prepared for this sort of argument and he protested his mind was free from all thoughts of malice:

I call God to record that as a private person I have done nothing unbeseeming an honest man, nor as I bear the place of a public person have I done anything unworthy my place. I confess that being very careful for the safety of the Queen and Realm, I have curiously searched out the practises against the same.

Mary continued on the attack and told Walsingham that she was only reporting what she had heard said of him. To discredit Walsingham’s evidence she declared spies were ‘men of doubtful credit, which dissemble one thing and speak another’. Flooding with tears she begged Walsingham not to believe those who declared she had consented to Elizabeth’s destruction. Through the tears she said: ‘I would never make a shipwreck of my soul by conspiring the destruction of my dearest sister.’ It was the performance of her life, but it was all in vain.

After much deliberation, it was decided that Queen Elizabeth’s safety could not be guaranteed so long as Mary Queen of Scots survived. Her execution took place on 8 February 1587 in the Great Hall at Fotheringhay. She dressed as if on a festival day and was led to the scaffold, upon which were a chair, a cushion and a block, all draped in black cloth. After prayers, Mary laid her head at the block and remained very still, repeating to herself, ‘In manus tuas, Domine.’

While one of the executioners held her steady, the other struck, but missed the neck. Struck in the back of the head, Mary was heard to whisper ‘Sweet Jesus’ before the second blow fell. Even this blow did not sever the head completely. A third blow was required before the head rolled completely free. The incident proceeded further into farce when one of the inept executioners went to lift up the head to acclaim the words ‘God save the Queen’ – he lifted it by the hair, only to find Mary had been wearing a wig. Her head fell to the floor with a thud and according to one witness, Robert Wynkfielde, Mary’s lips continued to move up and down for a quarter of an hour after the execution. Then Mary’s pet dog appeared from hiding under her petticoat and began lapping up the blood.