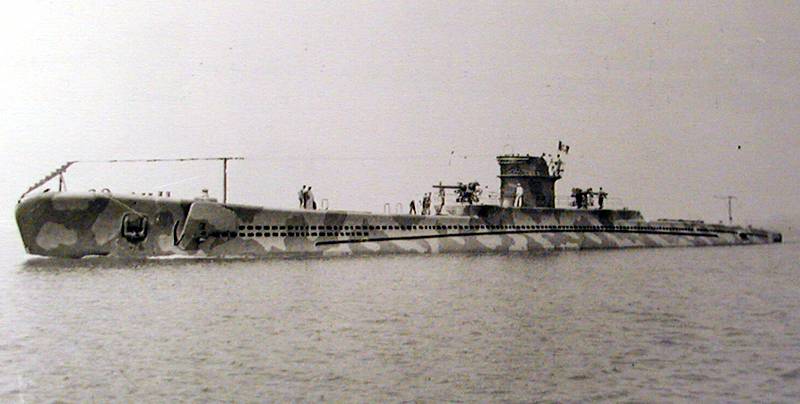

Italian Submarine “CAGNI”

When Benito Mussolini went to war against the Western Allies, he had at his disposal the world’s greatest submarine fleet in terms of tonnage. Only the Soviet Navy possessed a slight numerical edge. He was able to field 172 mostly modern, undersea warships, enough to simultaneously fulfill the numerous duties assigned to them: defending Italian coasts, intercepting enemy shipping, scouting for the surface fleet, transporting essential materials, and laying minefields. Nearly half of them could operate continuously for up to six months, ranging over 20,000 miles, far beyond the capabilities of any other contemporaneous submarines. Their torpedoes were among the best of World War Two; their all-volunteer crews, well-trained, skilled and spirited. If anything could truly make the Mediterranean Sea into Italy’s Mare Nostro, friend and foe alike believed the Duce’s submarines would effect the transformation.

Their expectations appeared to be confirmed just two days after his declaration of war, when the Bagnolini attacked two enemy light cruisers escorted by a destroyer squadron. A torpedo fired by Lieutenant Commander Franco Tosoni Pittoni struck HMS Calypso, sinking her about thirty kilometers southeast of the small island of Gavdo. In September, he escaped detection running submerged through the Straits of Gibraltar and into the North Atlantic. As a testimony to the skill of their operators, none of the Italian submarines that passed out and back into the Mediterranean from 1940 to 1943 were lost in the Straits deemed ‘suicidal’ by the Germans, who did indeed lose several U-boats around Gibraltar. Tight security in the form of vigilant corvettes and stationary hydrophones made movement through the narrow gauntlet hazardous.

Contributing to these military challenges was a powerful current that carried submerged vessels beyond their depth limits to sometimes collide with the rocky bottom. More than one boat was damaged by this navigational hazard, which was unknown until the first Italian submarine to leave the Mediterranean Sea for operations in the Atlantic Ocean successfully slipped through the Straits of Gibraltar on 13 June. Afterward, the British island-fortress was on high alert to prevent similar escapes. The Veniero had deftly infiltrated a formidable barrier of floating minefields and diligent patrols to team up with its U-boat comrades stationed at Bordeaux. British intelligence wrongly assumed she had sailed from Tobruk, where more submarines were supposedly lying in wait. Accordingly, the city was raided repeatedly by RAF Beaufort bombers, until a squadron of Italian destroyers sailed within range of the Egypto-Libyan border to shell British airfields at Salum, cratering the strip, blowing up repair stations, and inflicting irreparable damage on parked warplanes.

While sailing on the surface into the Bay of Biscay, the Bagnolini was attacked by a light bomber, but her accurate gunfire drove it away with the Blenheim’s starboard engine trailing smoke. On 11 December, Commander Franco Pittoni’s vessel joined German U-boats in action against Allied convoys, sinking the British cargo ship, Amicus, with a single torpedo. But the Italian submarine wallowed almost uncontrollably in North Atlantic weather, and returned suffering some damage to the Kriegsmarine base at Bordeaux. She sailed from there in early 1944, re-christened UIT-22 (U-boot-Italien, reflecting her Italo-German crew) commanded by Oblt.z.S. Friedrich Wunderlich. On 11 March, some 300 kilometers from Cape Town, UIT-22 was on her way to meet with U-178 for refueling, when she was attacked and sunk by pilots of South Africa’s 262nd Squadron. Their Catalina flying-boats were guided to the rendezvous by German radio messages of the kind British cryptographers had been intercepting the previous two years.

The fate of the former Bagnolini in some ways paralleled Italy’s entire undersea efforts during World War Two. Like that doomed ship, they got off with a successful start, but were soon hamstrung by a series of failings leading ultimately to disaster. These crucial faults were categorized and analyzed for the first time by Admiral Antonio Legnani, a veteran of the battles at Punta Stilo and Cape Matapan, where he successfully commanded his light cruiser, the Luigi di Savoia Duca Degli Abruzzi.

In “A Critical Examination of our Readiness and Results of our Submarine Warfare until early December 1941”, he pointed out that Italian boats were too slow: “This deficiency makes the reaching or passing (to then attack) of individual units or a convoy of them impossible.” Contributing to an inadequate speed was the drag produced by oversized Italian conning towers, which additionally slowed undersea maneuvers and, while surfaced, became large, visible profiles, unlike much smaller German versions. The U-boats also rode lower in the water, making them more difficult to see than the higher Italian free board. Italian engines were too loud, “with serious consequences in regards to detection by the enemy’s hydrophones.” Italian submarines were not designed to navigate through high seas, and therefore could not keep up with Kriegsmarine success against Allied convoys.

Germany’s Supreme U-Boat Commander, Admiral Karl Dönitz, originally had high hopes for augmenting his operational forces. At one time, “there were actually more Italian submarines than German U-boats operating in the Atlantic,” according to naval historian Robert Jackson. But the former handled so poorly in rough seas they achieved little. The final straw came on 25 May 1941, when Captain Giulio Ghiglieri was informed by radio that his submarine was the only Axis warship in the area where the German battleship Bismarck was immobilized and under attack by overwhelming surface forces. He tried to attack a pair of enemy cruisers, but the Barbarigo was unable to fire her torpedoes because the seas were too rough for her. Thereafter, Italian submarines were reassigned to the less turbulent Central and Southern Atlantic on solitary patrols.

Admiral Legnani wrote that Italian boats needed two to three minutes to submerge, more than twice as long as German submarines. Their turning radius was 300 meters, “thanks to the installation of a double rudder, where it is about 500 meters on our units.” U-boat torpedo-launchers generated no telltale air bubbles; Italian counterparts did. Italian torpedoes ran straight and true, but were sometimes diverted from the target by heavy swells. Worse, they only exploded on contact, when at least half of their blast potential was blown away from the target; German torpedoes were equipped with magnetic detonators that exploded with maximum effectiveness directly beneath an enemy vessel, breaking its keel.

The most distressful defect afflicting Italian submarines came to light at the very beginning of their operations. In early June 1940, serious problems with air-conditioning systems aboard the Archimede, Macalle and Perla were being attended to by repair personnel. But their efforts were interrupted by Mussolini’s declaration of war; a week later, the boats were ordered to the East African naval base at Massaua. During their first day at sea, crewmembers aboard all three vessels began experiencing debilitating nausea apparently caused by the air-conditioning units, which were partially shut down until cases of heat prostration continued to multiply. Conditions aboard Archimede were particularly severe, where some of the men, including two officers, suffered heat stroke. With the air-conditioning switched back on, many more exhibited extreme psychological disorders, including deep depression, loss of appetite, euphoria, hallucinations, and maniacal behavior.

On the night of the 23rd, a riot broke out among the crew, four men were killed, and Captain T.V. Signorini aborted his mission after restoring order, landing at the port of Assab. Mechanics rushed in from Massaua determined that methyl chloride–an odorless, colorless but highly toxic gas used as a coolant–had seeped into the ventilation systems and poisoned everyone aboard. It was replaced with relatively harmless freon, but most other Italian submarines continued to use methyl chloride for months thereafter!

A mid-1942 German newsreel documenting life inside the Barbarigo shows perspiring officers and crewmembers stripped down to their shorts, because they were reluctant to use the boat’s disreputable air-conditioning.

After the Archimede was restored to duty, she proceeded through the Red Sea, where she was on station for the next ten months. During that period, the few other Italian boats operating in this theater were virtually on their own, minus significant support from surface warships, with terrible consequences, as exemplified by the Torricelli. Enemy forces caught her on the surface outside Massawa during the dangerous daylight hours of 23 June, because malfunctioning ballast-tanks prevented her from diving. A pair of British gunboats and three destroyers converged on the partially disabled submarine, an apparently easy kill.

Hopelessly outnumbered and out-gunned, Lieutenant Commander Pelosi defiantly opened fire at 0530 with the Torricelli’s single deck-gun. A direct hit on the Shoreham’s deckhouse forced the gun-boat to disengage from the attack and make for urgent repairs at Aden. Taking advantage of the enemy’s astonishment, the suicidal Torricelli pressed forward at top speed, unloosing a spread of torpedoes at the destroyers. While they turned to avoid being hit, Pelosi directed his furiously firing deck-gun to concentrate its 100mm shells on the Khartoum, which erupted into flames.

So successful were the Torricelli’s maneuvers that the British were not able to score a hit until 0605, when its steering gear was knocked out and Pelosi wounded. He ordered the boat’s troublesome ballast-tanks manually forced opened, and she slipped beneath the surface of the Red Sea with the Italian tricolor still flying from her conning tower. In excess of 700 shells and 500 machine-gun rounds fired at the submarine in little more than half an hour had been unable to destroy her. Standing on the decks of Kandahar and Kingston, the destroyers that rescued them, survivors of the scuttled Torricelli witnessed the still-blazing Khartoum explode and sink. So impressed was Captain Robson with the Italians’ courage, he received Lieutenant Pelosi aboard the Kandahar with military honors.

Meanwhile, pressured between British forces descending from the north in Sudan and coming up from Kenya in the south, East Africa could not be expected to hold out indefinitely. Outside supplies and reinforcements could not reach the Italian defenders. Before the capture of Massaua, the Archimede and her fellow submarines made for the Italo-German base at Bordeaux, France. After passing south through the Gulf of Perim, evading enemy surface units and aircraft, they received enough supplies from a German tanker, the Northmark, to complete, in Jackson’s words, “an epic journey round the Cape of Good Hope”. The four submarines traversed 20,447 kilometers, eluding enemy interdiction and arriving in Bordeaux after sixty-five days at sea, most of them while surfaced, to great popular acclaim.

Their achievement was at least some compensation for the loss of East Africa. During the boat’s last cruise, she was under the command of Tenente di Vacello Guido Saccardo, prowling the Brazilian coast. On 15 April 1943, a U.S. Navy PBY Catalina piloted by Ensign Thurmond E. Robertson appeared 628 kilometers east-southeast of Natal. Each Italian submarine bristled with a quartet of 13.2mm machine guns, and Regia Marina crews often preferred to fight it out on the surface against attacking aircraft, rather than trust to the sluggish dive time of their boats. Saccardo’s men were no exception, and they put up such intense, accurate fire, Robertson had to abort a low-level, straight-in bomb-run, thereby affording the Archimede an opportunity to crash-dive. But she was too slow.

In desperation, Robertson put his lumbering ‘Gooney Bird’ into a sixty-degree dive, reaching a speed of 245 knots–far beyond the performance parameters for which the PBY had been designed. At 610 meters, five knots within terminal velocity, he pulled up to release four 160-kg Mk 44 Torpex-filled depth-charges. They exploded on either side of the submarine’s hull, smashing all light fixtures, disabling one of the 1,500-hp diesel engines, and blowing two forward hatches off their hinges. Unable to dive, the Italians were no less willing to surrender. For the next hour and twenty minutes, they fought off not only Robertson’s Catalina, but four other American flying-boats called to the scene. One of them piloted by Lieutenant Gerard Bradford, Jr. swooped in at a mere sixteen meters above the surface of the sea to drop four depth-charges on the Archimede. One tore through her aft hatchway, detonating torpedoes in the stern tubes, and she went down stern-first in a matter of seconds.

A pair of PBYs dropped three life-rafts for the survivors, Commander Saccardo among them. Of his fifty-four crewmembers, twenty-five were still alive, but not for long. Most were so badly wounded, they soon succumbed to their injuries. After twenty-nine days adrift in the company of his dying comrades, Engineer Giuseppe Lococo was washed ashore on Bailque, a small island at the mouth of the Amazon River, where he was found by local fishermen, who nursed him back to health. The twenty-six-year-old Sicilian coxswain was the only survivor.

The outcome of other encounters between attacking Allied aircraft and Italian submarine gunners mostly favored the latter. On 7 March 1941, look-outs aboard the Argo traversing the Bay of Biscay observed a Sunderland flying-boat in the distance. While any U-boat commander would have immediately crash-dived his vessel at the first sight of such a lethal threat, the Italians began communicating with the four-engine monster via signal lantern! Once they ascertained its identity, they allowed the Sunderland to approach to within 800 meters before opening fire, spoiling the pilot’s bomb run. By the time he resumed his attack, the Argo had vanished beneath the waves. A similar incident occurred exactly eight months later, when the Tricheco, attempting to make the Sicilian naval base at Augusta, was menaced by a Blenheim that veered away after having been hit by too many 13.2mm rounds. Off the coast of Brazil in early February 1943, gunners aboard the notorious Barbarigo caused an American Catalina pilot to prematurely drop his three bombs, which went wide of their target. The previous August 29th, she was attacked in the same waters by several PBYs. One was shot down and the others driven off, but after-gunner Carlo Marcheselli paid with his life for defending the boat.

He was not the only crewman to die in these sub-versus-plane duels, which usually saved the vessel, but not without casualties. Sergeant Michelangelo Canistraro was killed during a machine-gun attack carried out by a Sunderland against his submarine endeavoring to cross the Bay of Biscay on 15 February 1943. The Cagni escaped undamaged to complete 136 days at sea, the longest continuous mission undertaken by any Italian vessel during World War Two.