Russia’s progress

In the decades prior to Russia’s deployments to Ukraine (2014-) and Syria (2015-), its armed forces used EW to varying degrees during conflict in Chechnya in the 1990s and 2000s, as well as during its short war with Georgia in 2008. In Chechnya, it is thought that the gathering of communications intelligence (COMINT) on opposing forces, particularly in geo-locating sources of communications transmissions, was vital in finding and fixing enemy positions for targeting by artillery or airstrikes. In contrast, in Georgia Russian efforts to gather electronic intelligence (ELINT) on and direct jamming against ground-based air-surveillance and fire-control radars was said to have been poor, though this may have also been due to Georgian countermeasures.

Russia has since made efforts to regenerate its EW capabilities, and the deployments to Ukraine and Syria have provided an operational laboratory for the armed forces to refine and develop their EW doctrines. At the same time, they have to some extent offered a window to observe Russian capabilities. The US armed forces’ Asymmetric Strategy Group, writing in the publicly available study of Russia’s `new generation warfare’ (published 2015), said that Russia had observed, and looked to exploit, Western strategies. For instance, `because of maneuver warfare’s reliance on communication, Russia has invested heavily in Electronic Warfare systems which are capable of shutting down communications and signals across a broad spectrum’.

Russian EW in Ukraine was overtly offensive. Jamming helped sever Ukrainian military radio communications in Crimea, as Russia occupied and annexed that territory in early 2014. This was supported by the RB 314V Leer-3 uninhabited aerial vehicle (UAV)-equipped system, which was used to jam cellular networks, and the RP-377LA Lorandit COMINT system, which targeted high-frequency and very-/ultra-high-frequency communications. Jamming also affected the RF links used to control S-100 Camcopter UAVs assisting the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe observation mission in Ukraine. Russia looked to integrate these capabilities to improve its `reconnaissance-strike complex’. The Asymmetric Strategy Group stated that, in Ukraine, Russia used `a sophisticated blend of Unmanned Aircraft Systems, electronic warfare jamming equipment, and long-range rocket artillery’.

In Syria, Russia’s EW posture generally focused on force protection. The loss of a Russian Air Force Su-24M Fencer D combat aircraft to two Turkish Air Force F-16C fighters in November 2015 prompted Moscow to deploy additional EW systems. One month earlier, Russia had deployed the 1RL257 Krasukha-C4 jammer, which targets the X-band and Ku-band airborne radars typically used by combat aircraft and missiles, to protect Khmeimim air base in northern Syria. The Krasukha-C4 was supplemented by L-175V/VE Container/Khibiny and Leer-3 systems. The L-175V/VE jammer can be carried by Russian Air Force Su-30SM Flanker-H, Su-34 Fullback and Su-35 Flanker M combat aircraft.

Leer-3 may have been deployed to support Syrian Army operations by jamming insurgent mobile phones. It may also have been used to deliver morale-sapping text messages to opposing forces. Reports have circulated of the Russian armed forces also deploying equipment such as the RB-301B Borisoglebsk-2 COMINT system, which has also been used in the Ukraine theatre, and the Repellent-1 counter-UAV system, which is designed to interrupt the RF links between a UAV and its ground station. In June 2019, reports emerged that Israeli airspace had experienced GNSS jamming, possibly caused by Russian Army R-330Zh Zhitel systems being used to protect the Russian deployments at Khmeimim air base. Whether this jamming was deliberate, or an unintended consequence of operations, remains unclear.

Russian EW effects have also been observed in Europe. Moscow has been accused of using jamming against Norway and its Baltic neighbours. In March 2019, Oslo claimed that the Russian military had jammed GNSS signals in the country’s north during NATO exercises in October-November 2018. Russia’s earlier Zapad 2017 exercises saw EW used to prepare Russian forces for fighting in an electromagnetically contested environment. These EW efforts have not been performed in a vacuum. Operations in Ukraine and Syria showed that these form part of a wider strategy involving cyber attacks. Moscow has been accused of performing cyber attacks against Ukrainian critical infrastructure, and of targeting non-governmental organisations and opposition groups with cyber activity during its involvement in the Syrian conflict.

Russia’s Armament Development

The year 2020 was meant to end a decade in which the Russian Army had started to field a significant number of T-14 Armata main battle tanks in front-line units. However, by the end of 2019 none had entered operational service. Development and production challenges are contributory factors, as is cost, and instead the army has resumed upgrades to armour already in service, in particular the T-72B3 mod. and the T-80BVM.

Russia’s president announced during the June 2019 Army Military Show that 76 Sukhoi Su-57 Felon multirole fighters were to be delivered by the end of 2027. When it was finalised at the end of 2017, the State Armament Programme to 2027 only covered the manufacture of up to a further 16 of the aircraft in the early 2020s. Around 60 Felons were originally to have been delivered by the conclusion of the 2020 State Armament Programme; realising this ambition was difficult even when the plan was drafted in 2010.

Moscow continued during 2019 to pursue a number of nuclear-delivery systems intended to defeat US missile defences, including some beyond New START definitions. These included the Burevestnik (SSC-X-9 Skyfall) nuclear-powered, nuclear-armed long-endurance cruise missile, despite a series of test failures. While the Burevestnik remained some way from service entry, the Avangard hypersonic boost-glide programme was on the brink of entering the inventory. The MiG-31K variant of the Foxhound modified to carry the Kinzhal air-launched ballistic missile was also near to service entry as 2019 concluded. The Status-6/Poseidon nuclear-armed, nuclear-powered autonomous underwater vehicle remains in development.

Most Eurasian states continue to rely on ageing Soviet-era combat aircraft that are only slowly being replaced with more capable types. Belarus will become the second regional export operator of the Su-30SM Flanker H alongside Kazakhstan with the delivery due by the end of 2019 of the first four of 12 on order. A number of countries continue to operate early-model MiG-29 Fulcrum and Su-27 Flanker B aircraft in the fighter role including Belarus, Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan.

New weapons and research and development

The new strategic systems announced by President Putin in 2018 were already at an advanced stage of development when the announcement was made. Further progress has been made, but there have also been evident problems.

Tests of the Burevestnik (SSC-X-9 Skyfall) missile resumed in 2019. However, US sources indicate that nearly all the test launches failed. In August 2019, an accident occurred when a team was recovering wreckage from a previous missile test. Seven people were killed and there was localised radiation contamination. It is not surprising that the defence ministry has not elaborated on the nature of the problem, but it has said that further design development will take place before testing resumes.

Development of the Avangard glide vehicle is, however, more advanced. At least officially, development is complete and series production has begun. The weapon was successfully tested in December 2018, being launched from an RS-18 (SS-19) ICBM. It was announced that the first of these missiles with the Avangard glide vehicle will be deployed by the end of 2019. Russian analysts understand, based on unofficial data, that GPV 2027 includes equipping two RS-18 (SS-19) regiments. It is possible that the Avangard could also be fitted to other launch platforms, such as the RS-28 Sarmat ICBM that is currently under development.

Meanwhile, an experimental squadron of MiG-31K aircraft equipped with Kinzhal hypersonic missiles reportedly made more than 400 flights over the Caspian and Black seas in 2018, while the first Peresvet laser systems have been on trial combat duty since the end of 2018 with two divisions of the Strategic Rocket Forces. It is unclear whether these are operated by troops from the Strategic Rocket Forces or by air-force personnel, but Russian analysts understand that a Peresvet training centre is being built at the Russian Federal Nuclear Centre at Sarov. In February 2019, range trials were reported completed on the Poseidon UUV, and two months later the much-modified Project 09852 Oscar II-class submarine Belgorod was launched. This may be the first delivery platform for Poseidon.

2019 also saw construction continue at the Era military-technology park at Anapa on the Black Sea coast. Six additional research disciplines were also announced, including the development of weapons with novel physical principles (such as lasers and plasma), small satellites, geo-information systems and work on the use of artificial intelligence for military purposes.

Russia and future conflict

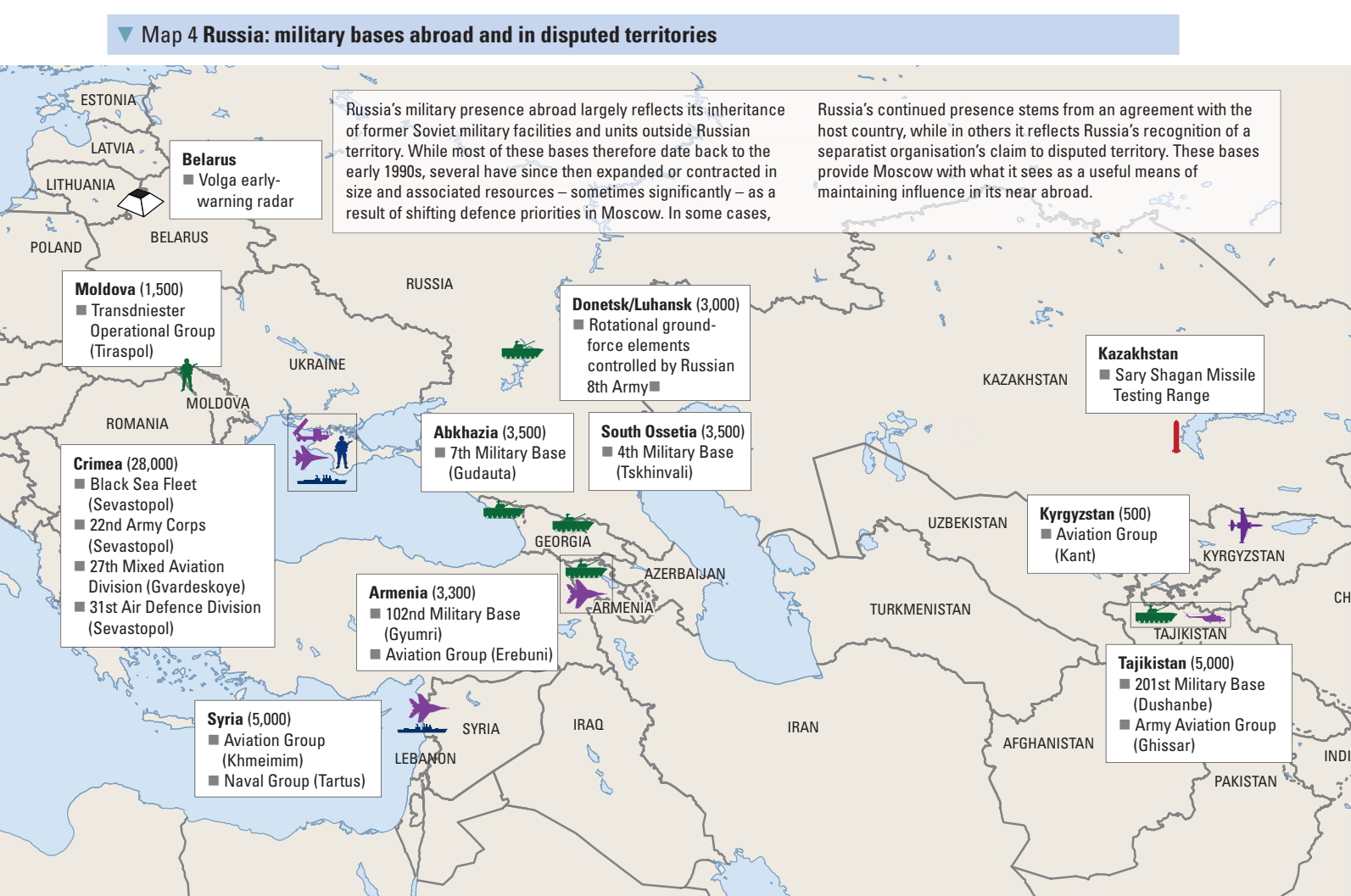

Since 2014, Russia has made increasingly visible use of its armed forces as a tool of national policy. Its military actions in Ukraine surprised transatlantic leaders, even though Russia had used military force before, in Georgia in 2008. John Kerry, the then US secretary of state, called Russia’s occupation of Crimea a `stunningly wilful choice’. Moscow’s actions led to speculation about how its leadership was `reinventing war’ and assessments about how Russian ways of war were evolving. Some of the more prominent of these, arguing that Russia was waging a form of `hybrid war’, emerged after Crimea was annexed, and after a retrospective reading of a 2013 article signed by General Valery Gerasimov, then newly appointed as Russia’s chief of the general staff. Entitled `The Value of Science is in the Foresight: New Challenges Demand Rethinking in the Forms and Methods of Carrying out Combat Operations’, this piece appeared in the 27 February 2013 edition of the Military Industrial Courier. Commentators introduced a range of catchy epithets – some coined by Western authors, others picked from the discussion among Russian sources – such as `war in the grey zone’, `non-linear war’ or `new generation war’, generally labelled as the so-called `Gerasimov doctrine’. These views have remained prominent, updated with `new’ or `2.0′ following another speech by Gerasimov in March 2019.

This emphasis may derive from Western strategists’ judgement that Russia is obliged to compete in indirect, asymmetric ways since it could not hope to win a direct conventional confrontation with NATO states. According to General Sir Nick Carter, the United Kingdom’s chief of defence staff, speaking in 2018, countries like China and Russia had been studying Western states’ strengths and weaknesses and had become `masters at exploiting the seams between peace and war’. Moscow would operate below the threshold of conventional war, weaponising a range of tools to pose a strategic challenge. These tools include, but are not limited to, energy supplies, corruption, assassination, disinformation and propaganda, and the use of proxies, including private military companies (PMCs). This is understood as a new Russian way of war that corresponds to `measures short of war’, and a preference for the manipulation of adversaries, avoiding military violence.

However, as specialists have pointed out, in the Russian debate there is no formulation resembling the `Gerasimov doctrine’. Moreover, giving too much weight to terms such as `new generation war’ may also hinder an accurate understanding of Russian views of contemporary conflict. These do reflect a changing security environment and non-conventional capacities, but also reflect significant focus on the use of combat power.

Russian debate on future conflict

There was some discussion in Russia in 2013 about `new generation war’, but since then Russian practitioners and observers have tended to use the term `new type’ warfare. This is an important distinction in Russian military theory, given the extensive and long-running debates about the changing character of war, including the idea of `sixth generation’ warfare referenced by MajorGeneral Vladimir Slipchenko following Operation Desert Storm in 1991. However, even though the term `hybrid warfare’ does exist in the Russian debate, it is used in reference to Western forms of war and how contemporary warfare more generally is evolving, not as some form of particularly Russian reinvention of war. Gerasimov himself noted, again in the Military Industrial Courier but in March 2017, that while `so-called hybrid methods’ are an important feature of international competition, it is `premature’ to classify `hybrid warfare’ as a type of military conflict, as US theorists do.

Indeed, rather than implementing `measures short of war’, there is evidence that Russia’s leaders have sought to enhance national readiness, as illustrated by the many exercises that bring together all elements of the state and move the country onto a war footing. These exercises – including the Vostok, Tsentr, Kavkaz and Zapad series of strategiclevel drills – seek to prepare Russia for fighting in a large-scale war. Furthermore, as is evident from the battlefields in Ukraine and Syria, while it may be considered preferable to achieve aims non-violently, this remains a theoretical ideal and the considerable weight of combat firepower is still a prominent feature of Russian conceptions of war fighting. Indeed, the scale of Russia’s combat deployment has regularly been announced by the Russian leadership, particularly with reference to operations in Syria. It is more appropriate to think, therefore, not in terms of Russian `measures short of war’, but perhaps instead in terms of Russian `measures of war’.

Russian views of warfare have evolved considerably even since the Russo-Georgian war of 2008, with important consequences for force development and posture. The Russian defence and security landscape is changing in response and the shifting balance between military and non-military resources to achieve political ends is often referenced by senior officials. But at the same time, the role of the armed forces in ensuring Russian security is being reinforced. As such, conventional combat remains a central element in Russia’s contemporary conception of conflict, with an emphasis on long-range precision strike and massed artillery fire, enhanced by new technology developments, including uninhabited systems and better command and control, and exploited by high-mobility forces.