Mackay learnt that Buchan was ‘taking the field’ and ordered Livingstone to monitor his progress. His command, based in Inverness, consisted of three regiments of infantry, his own regiment of horse and an unquantifiable number of dragoons. He was also instructed to ‘labour, by a detachment of the best of his men, to get a catch of them, or at least to hinder the grouth of their number: However, although Livingstone was able to learn of their whereabouts (apparently by threatening to torture a captured Jacobite agent, which then in Scotland was a lawful tactic) and to march to that vicinity, his problem being that of supplies. It was only with ‘great difficulty’ that the cavalry could find forage and the infantry their victuals. As soon as Buchan retired to the hills, he was obliged to return to Inverness. Livingstone gave Mackay ‘nothing but III News: Upon hearing this news, Mackay gathered 3,000 troops from Stirling, Dundee and Glasgow, to march to Perth. This was so that they could then march to counter any further Jacobite support that might accrue to Cannon and Buchan.

Livingstone discovered that despite the difficulties of coming to blows, he must act as soon as possible. Many of those who appeared to be supportive of the government were now intimating that they intended to join the Jacobites. Livingstone wrote that the Jacobite march ‘increased as a snow ball daily … affrighted and discouraged the country: He wrote to Mackay to tell him what his plan was and that many in the north were planning to join the Jacobites.

Jacobite forces

Jacobite officers claimed their force numbered between 1,400-1,500 men; Mackay that they had ‘much the same’ as Livingstone. Mackay also wrote that they had ‘800 of their worst men’ and had been reinforced by ‘some Badenoch men: The force included several companies of MacLeans, judging by later lists of prisoners. It also numbered many Camerons, too. The two forces were roughly the same number. Neither possessed any artillery to slow them down.

Livingstone marched his men eight miles from Inverness on 27 April in search of the Jacobites. They reached Brodie and remained there for two days, waiting for the slow-moving baggage trains carrying crucial supplies. They also waited for an additional three troops of dragoons and Captain Burnet’s Troop of Horse. Patience was also necessary to gain additional intelligence. Mackay ordered further troops and supplies to march towards Livingstone; Ramsay’s regiment of infantry, Angus’ battalion and five troops of cavalry.

The Jacobite forces were in Strathspey, ‘threatening to slay and Burn all that would not joyn’, according to Livingstone. On 30 April he learnt where they were: eight miles from Strathspey. This was in the land of the laird of Grant, a supporter of William III and a Scottish privy councillor. A captain of a company of Grant’s regiment which held a castle in Strathspey had reported that the Jacobite force had left Badenoch to march for Strathspey and had marched to within two miles of the castle.

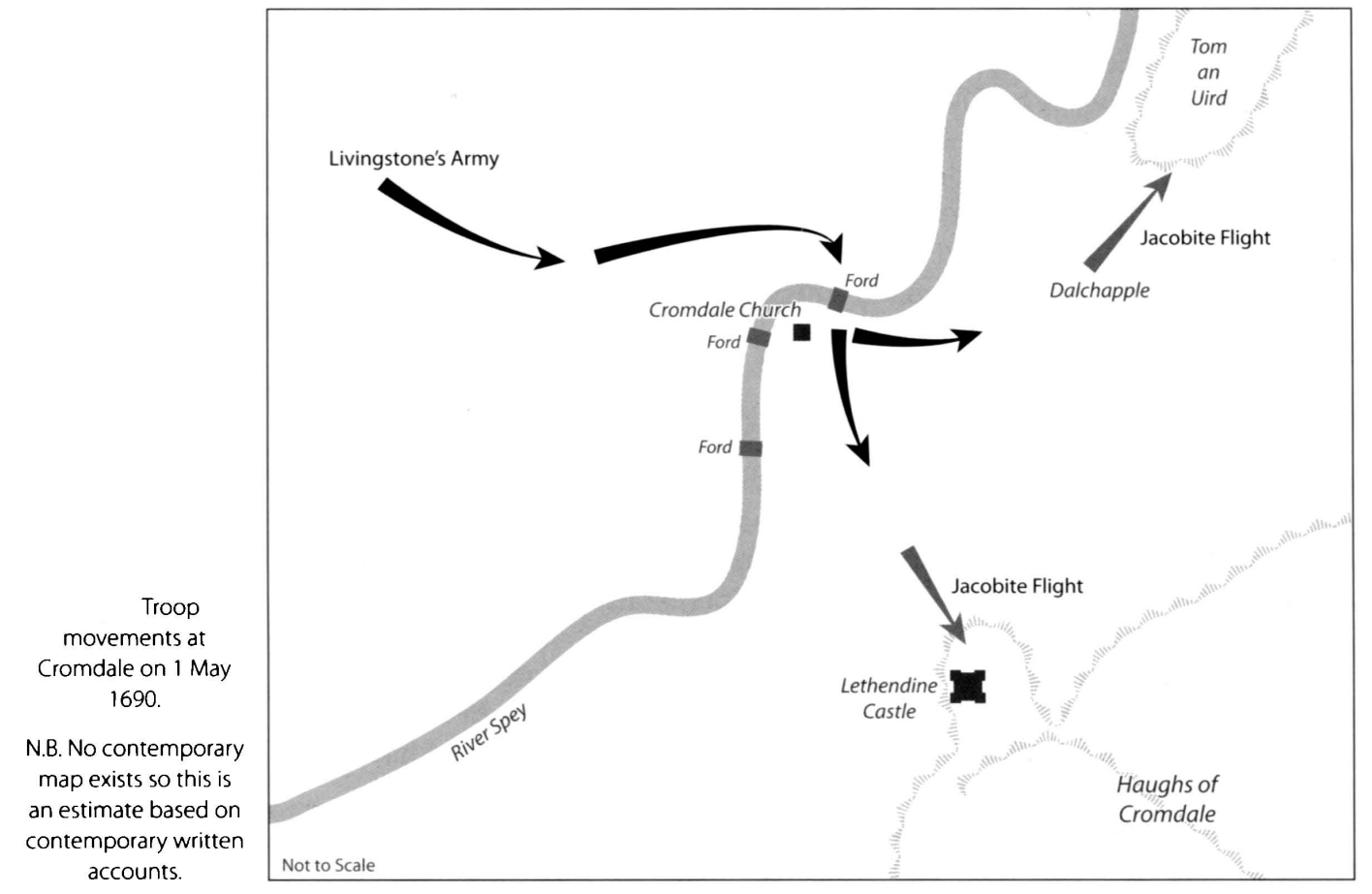

On 30 April Livingstone marched his forces through the night, and given that his men were tiring and were negotiating a difficult pass he considered halting to stop for the night, but an officer who knew the lie of the land convinced him to proceed. The Jacobite encampments became visible by its campfires. This was probably just to the west of the hills known as the Haughs of Cromdale and about a mile to the south-east of the Spey. Some men were above Dellachaple and some near the castle of Lethendry. Scouts discovered the lie of the land, how deep the river was and that ‘the Ground was somewhat boggish: Livingstone’s force was two miles from his enemy and had been marching through the evening and night. Livingstone wrote, ‘I forma a Design to attack them by surprise, for they did not know of our being arrived, but my Men and Horse being so extremely wearied, I gave them about half an hour to refresh themselves: Furthermore, the land was boggy and the nature and depth of the River Tay was unknown.

Captain Grant at Balla Castle knew of Livingstone’s advance and kept the castle gates locked in order to prevent any of those who had taken shelter there from leaving it and letting the Jacobites know of their peril. Livingstone’s forces were ready at two in the morning on the first day of May. Captain Grant met Livingstone and showed him where the Jacobites were. He offered to guide him there himself.

A council of war was held for Livingstone to brief his officers prior to the attack. He was still not certain whether an attack should take place. He asked his subordinates to see to the condition of their men to ascertain ‘if they were able to do it: The officers declared ‘they would stand by me to the last man and desired earnestly to go on: Fortunately for them, the Jacobite camp was on the plain, a mile and a half from any strong ground, for they did not know that their enemies were so close. Mackay later wrote, it was ‘just as if they had been led thither by the hand, as an ox to the slaughter:

A night attack is extremely risky, as would have been well known to soldiers in 1690. Only five years previously, Monmouth’s forces had marched through the night to surprise James Ifs army at Sedgemoor. It was a bold plan and a necessary one in order that irregular troops had a chance of defeating regulars. The attack failed because the attackers were unable to achieve the crucial surprise necessary for success. Monmouth’s army was decisively defeated the following morning.

Livingstone’s force marched by a covered way, the glen of Auchnarrow, to conceal their approach until the last moment and arrived by the river. It is presumed that no man pulled a trigger by accident as one of Monmouth’s had in 1685, and so surprise was achieved. There was a ford on the river Spey, near to the church, guarded by two companies of 200 Jacobites led by Captains Grant and Brody. It was now three in the morning. Livingstone had some infantry and dragoons skirmish with them, to distract their attention from the main assault, whilst the bulk of his forces marched a quarter of a mile towards another ford, guided by the knowledgeable Captain Grant. This thrust was spearheaded by two or three troops of Livingstone’s Dragoons, a troop of Tester’s Horse and Captain Mackay’s Highlanders. None of Grant and Brody’s men seem to have been assigned to give their comrades in the main camp warning and none defended the other ford, below Kyle-na-fhithich (Raven’s wood) as all rushed to the scene of action, leaving the other ford undefended.

Two troops of dragoons and Mackay’s company crossed the river without being noticed and they were able to advance unnoticed further by riding along a road concealed by birchwood. The rest of the infantry ‘ [ran] up to us, yet they marched after us with all diligence possible: Security must have been slack, with officers reliant on the men near the church being able to give ample warning in case on an attack. The Jacobites were asleep in tents and houses. Livingstone later wrote, ‘and then we do see them run in parties up and down, not knowing which way to turn themselves, being surprised: The Jacobites ‘take the alarm as moving confusedly as irresolute men: He then ‘commanded all the Horse and Dragoons to joyn, and pursued them, which affrighted them so. Apparently 100 Jacobites were killed ‘in the first hurry’.

The Jacobite account of the battle has it that , as soon as they recovered themselves, they formed into partys, made head against the enemy, and fought with that desperate resolution in their shirts with their swords and shields . These were the Camerons and the MacLeans. This stand may have occurred because they saw the Highlanders arrive at the hills before the cavalry, and so seeing him so weak, resolved to stand, but upon the sight of the rest of the party, which was following with all speed they could make, they began to run for it. Some ran to Tom Lethendie and some to the hills the MacDonalds had camped near Dellachaple and Garulin, escaping up the slopes of Tom Uird Luckily for him, Dunfermline had left the Jacobite camp on the previous day.

However, Livingstone wrote that they took themselves to the hills, at the foot of Combrel we overtook them, attacked them, killing betwixt three and four hundred upon the place and took about one hundred prisoners, the greater part of them officers. Killing confused and virtually defenceless men would have been easy for the cavalrymen, just as the slaughter of fleeing redcoats had been to the Highlanders at Killiecrankie. Livingstone stated that the Jacobites only escaped because mist descended so we could scarcely see one another, otherways the slaughter should have been greater’. Apparently few would ha lave escaped them, had not a sudden fog favoured the enemy’s flight. The retreat was successful for the pursuers horses were ready to collapse and the force was drawn up on low ground. Yet according to a Jacobite, ‘Sir Thomas was glade to allow them to retreat without attempting to pursue them.

The Jacobite leaders had been caught napping. On the first alarm Buchan sent away his nephew and some officers and men, though they later surrendered. Buchan escaped, though, he ‘got of, without hat, coat or sword: He was later seen, in a state of exhaustion, at Glenlivet, at a cousin’s house. Cannon also escaped; in a nightgown Dunfermline had, providentially, left the day before the fighting. Buchan and Cannon fled in different directions, the former looking for Cannon’s men. Livingstone had nothing but praise for his men, ‘The resolution and forwardness of the Troops was admirable’ and though most ofthe fighting had been by the cavalry, the infantry, unable to get to the front line, yet they ‘marched after us with as great Diligence as possible.

About 50 of the Jacobites, mostly gentlemen, went to the nearby Lethendy Castle with the intention of holding it to the last. Livingstone sent a messenger to them to offer them mercy if they surrendered. The Jacobites opened fire during this attempt at parley. Two grenadiers were shot dead and another was wounded. Lieutenant George Carleton of Leslie’s Foot had experience of using grenades from campaigning abroad, or so he claimed. Putting four into a bag he crept towards the castle by using an old ditch to reach an old house near to the castle. He intended to be close enough in order to throw his missiles into the castle.

He threw the first, which ‘put the enemy immediately into confusion’. The second grenade fell short. The third one exploded just after it had been thrown and so likewise was ineffectual. The fourth went through a window in the castle ‘so it increased the confusion, which the first had put them into; that they immediately called out to me, upon their parole of safety, to come to them: Carleton went to the barricaded main door, which had been reinforced by great stones. The Jacobites inside were ready to surrender if mercy would be granted.

Carleton returned to Livingstone to relate his account and pass him the news of the wish for a conditional surrender. Livingstone told Carleton to return to inform them that ‘He would cut them all to pieces, for their murder of two of his grenadiers, after his proffer of quarter: Carleton left, full of these melancholy tidings: but as he did, his commander came towards him. He said, ‘Hark ye sir, I believe there may be among them some of our old acquaintances (from the Dutch service). Therefore, tell them, they shall have good quarter: Carleton ‘very willingly’ took this news back and delivered it. The Jacobites immediately threw down their barricade and one Brody, who had earlier fought at the ford, came out from the main door. Apparently he had been wounded by having part of his nose blown off by one of the grenades Carleton had thrown. The two men went to Livingstone, who confirmed Carleton’s message and then all the Jacobites surrendered. Carleton wrote, ‘the Highlanders never held up their heads so high after this: Lady Roxburgh’s brother Alexander, an officer in the government army, was sorry that he was not there.

Losses

Cameron stated that ‘the loss on both sides was pretty equall: However, Livingstone stated that between 300 and 400 Jacobites had been killed; 20 officers and 400 others. A government report claimed that 900 were dead and 100 captured; surely an exaggeration. Another account states there were 400 Jacobite dead and 200 prisoners. John Cameron wrote that ‘Our Clan had a considerable loss at that unhappy business of Crombdale: The prisoners were sent to Inverness by 17 May, with the rank and file being accommodated in the castle and the officers allowed their liberty in the town but under guard. Yet there was not accommodation for them there. Most of the latter were soon sent to Edinburgh, guarded by 90 dragoons. By 26 May, 54 prisoners were there; including Sir David Ogilby and Archibald Kennedy. Their lot was not a happy one, as one Francis Beatton, in Edinburgh’s Tolbooth, complained to Argyll, ‘being taken at Crombdaill and ever since kept upon a very small allowance (2d per diem) which we could not subsist upon had it not been supplied by the charity of some tender hearted Christians.

The Jacobites also lost all their baggage, provisions, 1,000 arms and ammunition. The standards of King James and Queen Mary were captured. There was plunder for the victors, too, as Livingstone noted. Healths were drunk with wines taken from the Jacobite camp. Livingstone believed that he had had three men wounded, but none seriously, as well as having had a dozen horses killed and a greater number disabled. This ignores the two grenadiers killed at the castle.

A government report was that this was the ‘Entire Defeat of the most considerable Force of the Highland Rebels. Mackay wrote, ‘the news whereof did very much good to the King’s affairs both in Scotland and England, by abating the confidence of their Majesties’ enemies in both Parliaments. Carleton wrote that ‘The Highlanders never held up their heads so high after this defeat.

Mackay concluded that the victory had been due to numerous reasons. Firstly, Livingstone had procured intelligence that the Jacobites were in close proximity to him. Secondly that his troops were led in silence towards the enemy, thirdly that the inexperienced captain of the troops in the castle concealed his march. That Buchan camped his men in a vulnerable position contrary to usual Jacobite procedure. Mackay lastly wrote ‘tha’ Sir Thomas Livingstone did all that could be expected of a carefull diligent officer, the captain of the castle, altogether a novice, seemed to have had the greatest share in this favourable success.

The Jacobites dispersed: they had been on campaign for six weeks, had been defeated, scattered and had lost their supplies. They also wanted to see their families again. A government newssheet from Edinburgh, published a week later told that the Jacobites had told James that they could not hold out any longer, that they were in a starving condition and how ‘the rebels are in a great consternation, faring they shall have no relief from Ireland and doubts not but the common people will yield at the first approach of any of the King’s forces.

As with the fighting at Dunkeld, the results were as much moral than physical. Cameron wrote, ‘the ill conduct of General Buchan so discouraged the Lowland gentlemen, that not a man of them thought fit to joyn with him: Some Highland chiefs began to submit to the government; MacDonald of Largo and McAlastair of Loup did so on 16 June.