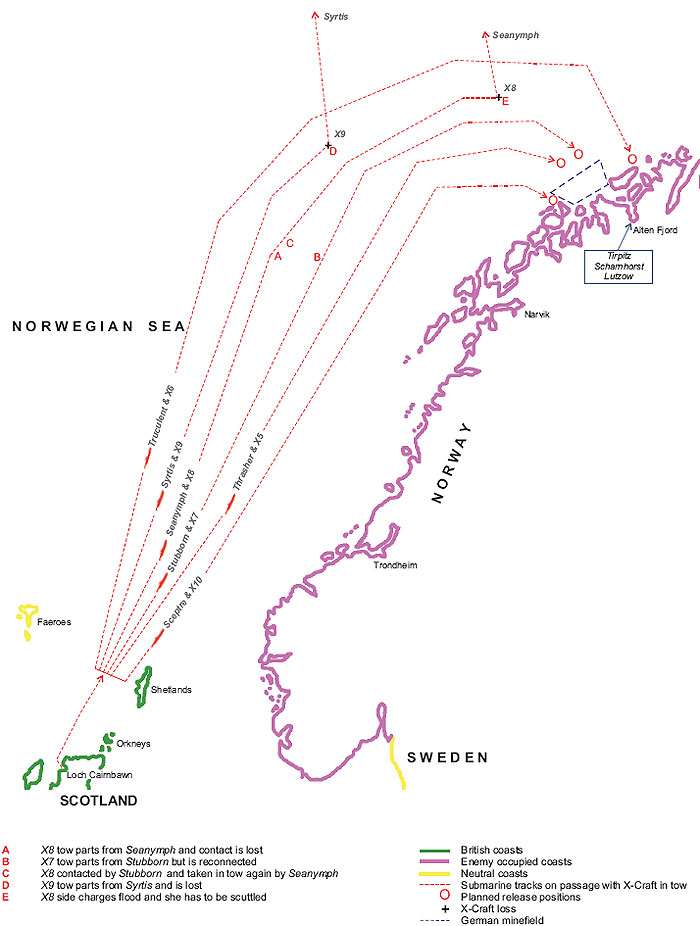

On 19 September only four X-craft remained operational. During the transit Rear Admiral, Submarines, had transmitted their attack orders. The X-5, X-6, and X-7 would attack the Tirpitz, X-8 would attack the pocket battleship Lutzow, and X-9 and X-10 would attack the battle cruiser Scharnhorst. With X-8 scuttled, the Lutzow was no longer a viable target, and with X-9 lost, X-10 would have to attempt the Scharnhorst alone.

That evening the Truculent, towing X-6, arrived at its release point off Soroy Island, which was well inside the Arctic Circle. The poor weather subsided, and the seas were good for transferring the passage and operational crews. There was a sense of excitement and fear among the operational crew. John Lorimer, second in command of X-6, wrote, “I can almost remember losing my nerve. Then the dingy came alongside the stern of Truculent and … I felt much better, the seamen wishing me ‘Good luck,’ and ‘See you in two days’ time sir.’ ” When the operational crew boarded the X-6, they found that one of the ballast tanks was cracked, the starboard side charge was beginning to take on water, and the periscope gland was leaking. These “minor” problems did not unduly disturb the operational crew and after the transfer of personnel, X-6 began its two-day voyage toward Kaafjord. Two other X-craft, X-5 and X-10, also transferred their operational crews and began their passage up the fjord.

Stubborn, towing X-7, was delayed a few hours owing to the incident with X-8. While they were transferring the operational crew, a floating mine lodged on the bow of X-7 a few feet from the starboard side charge. Lieutenant Place exited the midget and made his way to the bow. Once on the bow, he calmly dislodged the mine by kicking it free. The commander of Stubborn later relayed this story to Admiral Barry, and it became a bit of submarine legend. Place, however, is quick to point out that he noticed the horn on the mine had been crushed, indicating it was inoperable.

By 2000 on 20 September, all four X-craft had slipped their tows and were proceeding to their assigned targets. The tracks for X-5, X-6, and X-7 were almost identical (X-10 proceeded along an alternate path toward the Scharnhorst), yet the midgets never caught sight of one another. The X-craft negotiated the minefield off Soroy Island and entered the Stjernsund Channel without much trouble. By daylight they were cruising on the surface toward Altafjord. The weather was bright and sunny with a light breeze, and the channel was free of traffic.

Intelligence indicated that the best place for the X-craft to lie up during the night of the twenty-first was Brattholm Island, a small isolated outcrop that was within ten miles of the Tirpitz. As the midgets approached the island, the traffic began to increase. The midgets were required to dive frequently to avoid detection. At 1630, X-7 sighted the Scharnhorst, and although he was tempted to attack, Place proceeded as ordered to Brattholm Island.

The X-6, which also made Brattholm by evening, was experiencing difficulties with her periscope. The packing gland was leaking severely and required maintenance throughout the voyage. This attack periscope would be essential during the final approach on the Tirpitz. Without it the crew was blind and any attack would have to be conducted by gyroscope alone. Additionally, X-6 had “a nasty list to starboard” compounded by a flooded side charge. The crew of X-6 attempted to repair the problems but had limited success. That night the two X-craft remained surfaced in secluded areas of the island and charged batteries before the final leg of the attack. Periodically, the midgets submerged to avoid detection, but it was more precautionary than required.

On 22 September at 0145, X-6 departed Brattholm and began the ten-mile approach on the Tirpitz. With a partially flooded periscope, the commander, Lieutenant Cameron, dived to sixty feet and dead reckoned toward Kaafjord, the site of the Tirpitz. The weather was perfect for an attack. There were low clouds and rough seas punctuated by occasional rain showers. The first obstacle was the submarine net located at the mouth of Kaafjord. Cameron planned to approach the net at forty feet, lock out his diver, and maintain his position there until the diver cut an opening. Once the craft was through, the diver would be retrieved, and the X-craft would proceed into the inner harbor.

As X-6 approached the antisubmarine net, the diver, Dick Kendall, suited up and prepared to enter the wet/dry chamber. Kendall had practiced this procedure dozens of times, but it was never a pleasant experience. He said later, “You’re shut up in a space about the size of a water main with a lid over your head. You sit there, cold and lonely, waiting for the water to come up. You long for it, but you can’t let it in too fast because there’s a limit to what the body can stand. It takes about four minutes, and then when you’re completely covered and all the air is gone, the force on your body terminates in a sudden, final squeeze as the pressure inside equalizes with the pressure outside. It’s like a nasty kick in the head from a mule.”

It was now 0400 and the sun was just up. Less than half a mile from the net, Cameron ordered the midget to periscope depth to get one final look. As he looked through the periscope he realized his chances for success were diminishing quickly—the periscope was fully flooded. He wrote in his diary, “We had waited and trained for two years for this show and at the last moment faulty workmanship was doing its best to deprive us of it all. There might be no other X-craft within miles. For all I knew, we were the only starter, or at least the only X-craft left. I felt very bloody minded and brought her back to her original course … It might not be good policy, we might spoil and destroy the element of surprise, we might be intercepted and sunk before reaching our target, but we were going to have a very good shot at it.”

Cameron dove to sixty feet. Inching his way along, he removed the periscope eyepiece and cleaned it once again. As he approached the antisubmarine net he brought the X-craft to thirty feet. The crew was prepared to cut their way through the net when Cameron heard the propellers of a ship overhead. In a very risky move, he ordered the X-craft to the surface and proceeded “full ahead on the diesel.” X-6 passed right through the parted net in the wake of a small coaster. No alarm was raised, and after-action reports indicate X-6 went undetected. Had Cameron come to periscope depth instead of surfacing, the X-craft would have been too slow to pass through the nets before they closed.

Earlier in the evening at just past midnight, X-7 had left Brattholm and by 0400 had slipped through a large boat passage in the antisubmarine net. Now both X-6 and X-7 had only one more obstacle to overcome, the antitorpedo net. Place and Cameron had two different plans for overcoming the net. Place intended to dive deep and go under the net. Cameron’s initial plan was to cut through the net.

Once through the antisubmarine net, X-6 was only three miles from the Tirpitz. Cameron slowed the boat to two knots and maintained a depth of seventy feet. A final check of the periscope showed it had flooded again. Cameron stripped down the lens and dried the prism for the last time. Unfortunately the leak was on the outer casing and no amount of cleaning would last for long. After refitting the lens, Cameron came to periscope depth. There he could see a tanker refueling two destroyers and beyond them the Tirpitz. He took a bearing on the Tirpitz and dove to thirty feet. The water in the fjord was a mixture of fresh and salt, and it made it difficult to maintain proper depth. Even with this problem the crew was reluctant to operate the pumps for fear of being detected by hydrophones.

From the submarine net to the stern of the tanker took X-6 over an hour. Coming up for one final look, Cameron almost collided with the cable connecting the destroyer to her mooring buoy. Diving quickly he avoided the cable and remained undetected. Moments later an electrical fire broke out in the control room, filling the small space with smoke. The crew reacted instantly and extinguished the fire. Cameron looked around the control room and took stock of his crew and X-craft. It had been almost thirty-five hours since X-6 had released from the parent submarine. The crew was physically exhausted from the cold and lack of sleep. The periscope was almost completely flooded, the hoisting motor was burned out, they were listing fifteen degrees to port, and a steady stream of bubbles followed them throughout their transit.

Cameron did not know the status of the other two X-craft assigned to attack the Tirpitz. If he decided to continue with the attack, it would have to be completed no later than 0800. This was the time when the side charges would explode if the other X-craft had succeeded. He realized that X-6 and her crew would not survive eight tons of explosives at close range. If he turned back now there was a chance of scuttling the midget and escaping across the mountains toward Sweden. The Royal Navy had provided escape and evasion equipment necessary to exist for a short while. This included boots, clothing, compasses, maps, medical supplies, handguns, food, and money. Cameron knew, however, that beyond the mountains lay a vast expanse of arctic wilderness in which the submariners would probably not survive. Cameron consulted the crew as to whether they wanted to continue the mission with the X-craft in such poor condition. There was very little discussion and the decision was made to continue on.

Godfrey Place, in X-7, had crossed the antisubmarine net and was proceeding toward the Tirpitz when the X-craft was forced deep by a picketboat on patrol. While avoiding detection, X-7 ran afoul of a discarded section of antitorpedo netting once used to protect the Lutzow. Place spent an hour executing a series of pumping and blowing maneuvers before X-7 finally broke free. Unfortunately, the actions damaged the gyroscope and trim pump, and within minutes the X-craft was caught again on a stray cable. Finally, by 0600 X-7 was free from the entanglement and heading toward the antitorpedo net and the Tirpitz.

At 0707 X-6 reached the northern end of the antitorpedo net and luckily found the small boat gate open. According to Comdr. Richard Compton-Hall, “This gate was guarded by hydrophones and a special guard boat but, unwisely, the Germans stood down the guard at 0600. At 0700 [actual time 0707] Cameron slipped through the narrow entrance, keeping just shallow enough to see the surface through the glass scuttles in the pressure hull.”

Once through the gate the X-craft was within a hundred yards of the now-unprotected Tirpitz. Unknown to Cameron, X-7 arrived at the southern end of the antitorpedo net at 0710. Place, having been informed that the net only extended to sixty feet, dived to seventy-five feet and attempted to go under the obstacle. The intelligence estimates on the net defenses had been wrong. There were actually three nets, each forty feet long. In his after-action report Place wrote:

Seventy-five feet and stuck in the net. Although we had still heard nothing, it was thought essential to get out as soon as possible, and blowing to full buoyancy and going full astern were immediately tried. X.7 came out, but turned beam on to the net and broke surface close to the buoys … We went down immediately … and the boat struck again by the bow at 95 feet. Here more difficulty in getting out was experienced, but after five minutes of wriggling and blowing she started to rise. The compass had gone wild and I was uncertain how close to the shore we were; so we stopped the motor, and X-7 was allowed to come right up to the surface with very little way on. By some extraordinary luck we must have passed under the nets or worked our way through the boat passage for, on breaking the surface, I could see the Tirpitz right ahead, with no intervening nets, and not more than 30 yards away … ‘40 feet.’ … ‘Full speed ahead.’ … We struck the Tirpitz on her port side approximately below ‘B’ Turret and slid gently under the keel. There the starboard charge was released in the full shadow of the ship … ‘60 feet.’ … ‘Slow astern.’ … Then the port charge was released about 150 to 200 feet farther aft—as I estimated, about under ‘X’ turret … After releasing the port charge [about 0730] 100 feet was ordered and an alteration of course guessed to try and make the position where we had come in. At 60 feet we were in the net again … Of the three air-bottles two had been used and only 1200 pounds [less than half] was left in the third. X-7’s charges were due to explode in an hour—not to mention others which might go up any time after 0800 … In the next three-quarters of an hour X-7 was in and out of several nets, the air in the last bottle was soon exhausted and the compressor had to be run.

In the meantime, the watch aboard the Tirpitz had spotted X-6 and shouted the alarm. Fortunately for the X-craft, the Tirpitz was constantly conducting antisubmarine and antiswimmer drills, and the crew had become complacent. The chief of the watch questioned the crewman’s sighting, and it was not until 0712, when X-6 broke the surface eighty yards abeam of the battleship, that the Tirpitz’s crew was energized. Even with this sighting, the actual alarm did not sound until 0720. When the alarm was eventually sounded, the crewman on the bridge issued five short blasts. This signal was incorrect and called for the crew to man their watertight doors, as if the Tirpitz had hit an iceberg. This created considerable confusion and added to the delay in reacting to the X-craft. During the time between the second sighting and the alarm, Cameron maneuvered X-6 underneath the Tirpitz. The midget got entangled in wires dangling from the port side, and Cameron had to blow his way out. As X-6 shot to the surface, the craft was engaged by small arms and hand grenades from the crew of the Tirpitz.

Cameron submerged immediately and backed the X-craft underneath the Tirpitz’s hull, in the vicinity of B turret. There he jettisoned his two side charges, set the timers for 0815, then ordered the crew to destroy all the secret material. It was clear now that escape was impossible. Cameron surfaced for the last time, opened the sea cocks to scuttle X-6, and ordered the crew to abandon ship. A German picketboat captured the crew and attempted to tow the X-craft to the beach. Fortunately for the British, the sinking midget was too heavy, and the Germans had to cut the towline. X-6 sank to the bottom. Cameron and his men were taken aboard the Tirpitz. They felt certain the Germans would have them shot. Instead, however, the crew of the Tirpitz was relatively hospitable and offered the British coffee and schnapps. At 0812 when the charges detonated, however, the captain immediately ordered the four crewmen of X-6 shot as saboteurs. Fortunately, he changed his mind.

Meanwhile X-7 was attempting to escape. Lieutenant Place stated in his after-action report:

At 0740 we came out while still going ahead and slid over the top of the net between the buoys on the surface. I did not look back at the Tirpitz at this time as this method of overcoming net defenses was new and absorbing … We were too close, of course, for heavy fire, but a large number of machine-gun bullets were heard hitting the casing. Immediately after passing over the nets all main ballast tanks were vented and we went to the bottom in 120 feet. The compressor was run again, and we tried to come to the surface or to periscope depth for a look so that the direction indicator could be started and as much distance as possible put between ourselves and the coming explosion. It was extremely annoying, therefore, to run into another net at 60 feet. Shortly after this [0812] there was a tremendous explosion. This evidently shook us out of the net, and when we surfaced it was tiresome to see the Tirpitz still afloat.

The explosion left X-7 “a bit of a mess inside” with water rushing in quickly, the compass and periscope broken, and only one light functioning. Place sat on the bottom of the fjord momentarily, trying to decide the best course of action. He wanted to beach the X-craft but was concerned about “giving the enemy full knowledge of the boat.” Place later recalled, “We all decided that we weren’t really going to do any good at all by going on. So I thought the safest thing was for us to try to [surface and] get out … If we were being shot at it was up to me to go outside [and risk being shot by the Germans].”

Place exited the X-craft first, waving a white sweater to signal surrender. As he jumped from the midget into the water, the force of his weight pushed the small X-craft underwater. The inrush of water forced the crew to secure the hatch, and X-7 sank to the bottom. Place didn’t know why the midget sank. “Whether they, the first lieutenant took the boat down or whether it hadn’t got enough buoyancy lift, I don’t know.”29 Place was taken to the Tirpitz and fully expected the crew of X-7 to exit the craft using the emergency lock-out procedures.

“See,” Place told, “I’d briefed them carefully on doing an [emergency] escape … They’d practiced diving and things … We tried so many submarine escapes I think what went wrong was they were too slow flooding up and on oxygen if you’re slow flooding up you get oxygen poisoning.”

Unfortunately, the deep depth of the fjord forced the crew to wait for forty-five minutes before the internal pressure could equal that of the sea. During that time, the oxygen in their breathing apparatuses was exhausted, and only one crewman, Sublieutenant Robert Aitken, escaped.

The eight tons of amatol that exploded underneath the Tirpitz did not sink the battleship, but it did severely damage all three main engines, all lighting and electrical equipment, one generator room, the hydrophone station, antiaircraft control positions, port rudder, range-finding equipment, and both B and X turrets. One German was killed and forty wounded as over five hundred tons of water rushed into the interior compartments of the battleship. As a result of the action, the Tirpitz never went to sea again. She was eventually towed to another berth off Haakoy Island where RAF Lancaster bombers sank her in place.

The surviving crews of X-6 and X-7 were imprisoned in German POW camps and eventually repatriated after the war. The fate of X-5 remains a question to this day. Cameron said he saw the Germans sink X-5 with their heavy guns, but a postwar search of the fjord only found X-6 and X-7. It is more likely that X-5 never made Kaafjord. To Place it didn’t matter. He said later, “It doesn’t to me make much of a difference whether he attacked or didn’t attack … Henty Creer [commander of X-5] was a jolly good chap and I know he did the best he possibly could.”

X-10, whose target was the Scharnhorst, had mechanical difficulties and decided not to attack the pocket battleship for fear of compromising the rest of the operation. The crew of X-10 eventually rendezvoused with her parent submarine, scuttled X-10, and returned to England. The Seanymph and Sceptre remained in their patrol sectors until 4 October in the event that some of the X-craft crews escaped. They returned to Lerwick, Scotland, on 7 October, and Operation Source was officially ended. Admiral Barry later remarked,

I cannot fully express my admiration for the three commanding officers … and the crews of X-5, X-6, and X-7 who pressed home their attack and who failed to return. In the full knowledge of the hazards they were to encounter, these gallant crews penetrated into heavily defended fleet anchorages. There, with cool courage and determination and in spite of all the modern devices that ingenuity could devise for their detection and destruction, they pressed home their attack to the full … It is clear that courage and enterprise of the very highest order in the close presence of the enemy was shown by these very gallant gentlemen, whose daring attack will surely go down to history as one of the most courageous acts of all time.