BACKGROUND

On 27 March 1942, British commandos attacked and destroyed the Normandie dry dock at the French port of Saint-Nazaire. This action was undertaken to prevent the German battleship Tirpitz from sailing from her anchorage in Norway into the Atlantic and then seeking refuge at Saint-Nazaire. The Normandie dry dock was the only facility in the Atlantic capable of repairing the fifty-three-thousand-ton vessel, and the Germans would not risk exposing the Tirpitz to action without being assured of adequate repair facilities. Nonetheless, the Tirpitz, the sister ship of the Bismarck, still threatened the North Sea and required constant attention by both British and American forces to keep her in check.

After the raid on Saint-Nazaire, several plans were formulated to sink the Tirpitz in Norway, but by early 1943 Winston Churchill was getting impatient and wrote to his chief of staff, General Ismay, “Have you given up all plans for doing anything to Tirpitz while she is in Trondhjem? We heard a lot of talk about it five months ago, which all petered out. At least four or five plans were under consideration. It seems very discreditable that the Italians should show themselves so much better at attacking ships in harbour than we do … It is a terrible thing to think that this prize should be waiting and no one be able to think of a way of winning it.”

Unbeknownst to Churchill, the British admiralty had been working for two years on developing a midget submarine capable of penetrating the Norwegian fjords and winning the prize. In early May 1941 volunteers were recruited “for special and hazardous duty.” These men, including Lt. Don Cameron, who would later participate in Operation Source, were instrumental in the development and construction of the first operational X-craft. Originally conceived by Cromwell Varley of Varley Marine, Ltd., the X-craft midget submarine was constructed by three different shipbuilders who independently built the bow, center, and tail sections. Twenty other contractors were responsible for the internal workings of the craft. This distribution of effort resulted in a submarine whose “design was a little unsound in many respects.”

The first submarine available for trial was the X-3, built under extreme secrecy and launched on 19 March 1942. Upon completion of X-3’s trials, the midget submarine was sent by rail to the submariners’ new base at Port Bannatyne, Scotland, subsequently renamed HMS (His Majesty’s Station) Varbel. In the meantime, additional volunteers were recruited and began to be screened for suitability. They were sent to the submarine base HMS Dolphin at Gosport, England, where they underwent six weeks of screening that included physical training, six one-hour dives in a nearby lake, and “theoretical” courses on the X-3 submarine. Most of the men were unaware of the nature of the operation.

In mid-January 1943 six more midget submarines designated X-5 through X-10 were delivered. The 12th Submarine Flotilla was formed under Capt. W. E. Banks to coordinate with RAdm. C. B. Barry (whose title was Rear Admiral, Submarines) on the “ ‘training and material of special weapons’; and to his flotilla X-5-X-10 were attached, with Bonaventure [Acting Capt. P. Q. Roberts, R.N.] as their depot ship.”

The X-5 series was larger and better designed than the prototype X-3. It was fifty-one feet long and weighed thirty-five tons fully loaded. It had an external hull diameter of eight and one-half feet except directly under the periscope, where it extended an additional few inches. The internal space was significantly shorter and more cramped with a diameter of five feet, nine inches. The only place a man could stand up was underneath the periscope.

The craft was divided into four compartments. The forward space was the battery compartment that provided power for all electrical equipment in the X-craft, including the pumps, lights, and main motor. The second compartment was the wet/dry chamber and head (bathroom). This space was used to lock out the diver who would be tasked with cutting antisubmarine or antitorpedo nets. The third compartment was the control room. Inside this small space the crew piloted the X-craft by a simple system of wheels and levers that controlled the helm, hydroplanes, and main ballast tanks. The control room had two periscopes used by the conning officer; a short wide-angle periscope for night operations while surfaced, and a slender, telescopic attack periscope for while submerged daytime operations. The control room also served as the galley where the crew could heat up tin cans or boil a pot of water for tea or coffee. The aft compartment contained the main motor used for submerged propulsion and a London bus engine that normally propelled the X-craft on the surface but could be used for submerged operations at periscope depth.

Submerged, the craft cruised at two knots with a top speed of five and one-half knots. On the surface it could make six and a half knots depending on the sea state. Being a diesel submarine, the X-craft submerged only when absolutely necessary and spent most of the night surfaced to recharge batteries. When surfaced the captain would normally trim the craft so that it barely protruded above the water. This reduced the visual signature and radar cross section and allowed the captain to lie along the outer casing of the submarine and conn the craft from the surface. This technique, however, was seldom used for a variety of reasons.

The X-craft was capable of conducting dives to over three hundred feet, but most of the submerged cruising was around sixty feet. The midget submarine was equipped with two viewing ports that allowed the captain to observe the diver, who would normally stand on the X-craft while cutting through antitorpedo nets. These ports had steel shutters that could be closed during deep dives or depth charge attacks.

The X-craft was specifically designed to attack the Tirpitz at her berth in Norway, so it had no torpedoes, rockets, or surface guns. These weapons would be useless in a confined area like the fjord. The X-craft did come equipped with two side charges (referred to as side cargos), one on each side, each composed of two tons of amatol high explosive. The charges were contoured to the outer hull and made neutrally buoyant.

Thomas Gallagher explained in The X-Craft Raid that “when a side charge was released [by turning what looked like an ordinary steering wheel inside the X-craft], a copper strip between the hull and the charge peeled off, unsealing the buoyancy chamber and allowing enough water to enter to make the charge negatively buoyant.” The charge, now negatively buoyant, would sink to the bottom of the fjord below the Tirpitz. A timer was installed to allow the X-craft crew to dial in the desired delay and extract before the explosive detonated.

Admiral Godfrey Place, commander of X-7, was not completely satisfied with this configuration. “We at the time really thought … if we made the charge positively buoyant to go upwards it would stick to it [the Tirpitz] without any problem … we would really have preferred to have the charges floating upward, but the explosive experts claimed that it was better to send it [the side charge] down to the seabed to make the sort of tamping effect to create a vast explosion over a longer area. Our outlook was a little doubtful. We’d rather have blown a darn great hole in the thing.”

The biggest drawback of the midget submarine was its limited endurance. The published specifications indicated that the range was fifteen hundred miles at four knots, but in reality the range was limited by human duration. Although a crew of four was able to exist inside the craft for extended periods, they were not able to actually operate the controls for much farther than three hundred miles while submerged. The conditions were just too physically taxing. This forced the Royal Navy to tow the X-craft (with passage crews inside that merely maintained the depth) for the first twelve hundred miles from Scotland to the release point off the Norwegian coast. This towing effort presented several problems during the actual mission, but it was still felt to have been an effective way of getting the X-craft from Scotland to Norway.

During the course of the next several months, plans were prepared for attacking German shipping in three separate operational areas of Norway. This would allow for any change in German berthing plans. On 11 September 1943, six conventional submarines would tow the six X-craft from Loch Cairnbawn, Scotland, to a position 75 miles west of the Shetland Islands and then follow routes 20 miles apart until they were approximately 150 miles from Altenfjord. At this point the submarines would navigate to their assigned release points off Soroysund (Soroy Sound) and prepare to detach the X-craft. A change from passage to operational crew was authorized for any time past 17 September when the weather and tactical conditions allowed. The entrance to Soroysund was extensively mined by the Germans. Nevertheless, the Royal Navy planned the following:

“The X craft were to be slipped in positions 2 to 5 miles from the mined area after dusk on D Day [20 September], when they would cross the mined area on the surface and proceed via Stjernsund to Alten Fiord, bottoming during daylight hours on 21st September. All were to arrive off the entrance to Kaa Fiord at dawn 22nd September and then entering the Fleet anchorage, attack the targets for which they had been detailed. These would be allocated by signal during the passage, in the light of the most recent intelligence.”

The conventional submarines were to return to their patrol sectors and await the return of the X-craft. If no rendezvous were effected, the submarines were to proceed to one of the bays on the north coast of Soroy and attempt a link-up on the nights of 27–28 and 28–29 September. As a tertiary plan the X-craft crews were authorized to proceed to the Kola Bay in Russia, and a British minesweeper would be looking out for them between 25 September and 3 October.

THE BATTLESHIP TIRPITZ

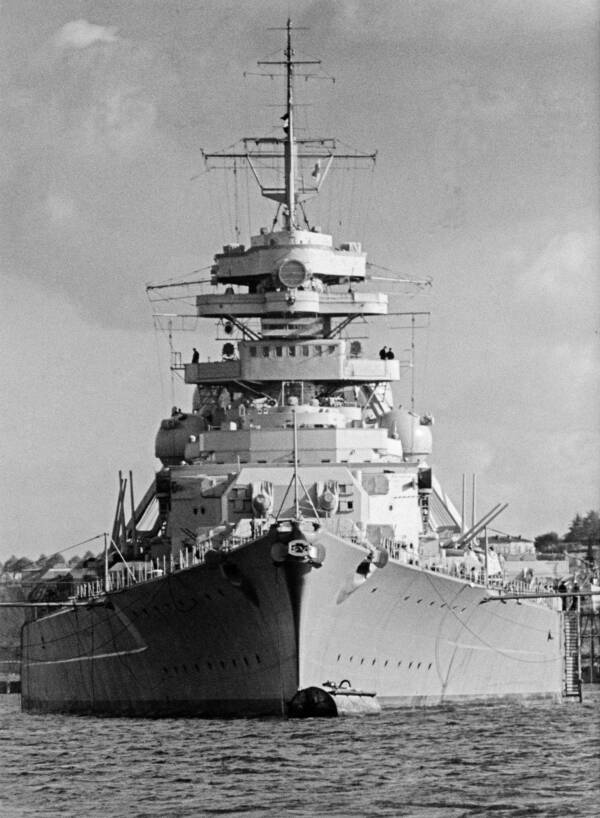

The Tirpitz was commissioned in December 1940, but not actually completed until February 1941. She was the largest battleship of her time with an overall length of 822 feet and a beam of 118 feet. Fully loaded, the Tirpitz displaced fifty-three thousand tons with a draft of thirty-six feet. The ship was powered by twelve boilers in six separate compartments. These boilers produced 163,000 shaft horsepower, allowing the battleship to reach speeds in excess of thirty knots. Topside the Tirpitz was equipped with eight 15-inch guns and twelve 5.9-inch guns for surface action. For air defense she had sixteen 4.1-inch, sixteen 37mm, and eighty 20mm antiaircraft guns. Additionally, the Tirpitz carried four Arado reconnaissance and light-bomber aircraft.

Although the topside armament was impressive, it did not unduly concern the X-craft crews. What did matter to the planners of Operation Source was the Tirpitz’s hull, which was encased in twelve-inch steel at some locations. This steel band protected the battleship in strategic areas including her control room amidships, boilers and turbine rooms, gunnery control rooms, electrical controls, and magazines. This steel protection coupled with the interior steel bulkheads made the Tirpitz invulnerable to torpedo attack, and 5.9-inch steel decks protected her vital areas from high-altitude bombing. However, thirty-six feet below the waterline, the Tirpitz keel remained a soft underbelly. It was this weakness that the British hoped to exploit.

The Tirpitz and her battle group, which included the twenty-six-thousand-ton Scharnhorst and several destroyers, were berthed in Kaafjord, Norway, which was located well above the seventieth parallel and over twelve hundred miles from Scotland. Surrounded by steep, virtually treeless mountains, the fjord was fed by waters from the Gulf Stream, which kept it ice-free year around. For most of the year the ground was covered with snow, and the sun remained high on the horizon. When the snow did melt, it sent mountainous slabs of ice crashing into the water, creating a brackish environment of fresh and salt water.

Using the terrain as a natural fortress, the Germans placed radar stations and antiaircraft batteries on the mountaintops and flew fighter aircraft to protect the fleet from British bombers. In the fjords, the three islands of Stjernoy, Altafjord, and Altenfjord funneled intruders into a channel where antisubmarine nets were placed and picketboats patrolled the waters. As extra protection in the unlikely event that a submarine negotiated the channel or a dive-bomber attempted a suicide run in the Kaafjord Valley, an antitorpedo net surrounded the high-value targets preventing any possible damage. The net, which completely surrounded the Tirpitz, was constructed of woven steel grommets and was capable of stopping a torpedo moving at fifty knots. Based on aerial photos and reports from Norwegian resistance, British intelligence believed that the net only extended sixty feet down from the surface. It was not apparent that the Germans had actually constructed three nets, one that extended from the surface to 40 feet beneath the surface and two more that reached to the seabed 120 feet below. To augment all these precautions, the Germans added smoke screen equipment to conceal the battle group and patrolled the surrounding roads and villages to prevent Norwegian resistance from conducting reconnaissance or sabotage operations.

Intelligence on the target area was difficult to obtain. Kaafjord was well outside the combat radius of British-based aircraft. Consequently, the Royal Air Force (RAF) arranged to have the Soviets construct an airfield outside Murmansk. From here Mosquito reconnaissance planes, flown by the RAF, could photograph the fjord and develop the film immediately upon return to Russia. The processed film was returned to England via Catalina long-range aircraft. Norwegian resistance based at Kaafjord collected detailed intelligence on the daily habits of the officers and crew. They were able to determine picketboat patrol routes, identify net defenses, watch general-quarters drills, and most importantly ascertain the maintenance schedules of the guns and sonar equipment. The two main Norwegian agents were Torstein Raaby and Alfred Henningsen. After the war Raaby joined Thor Heyerdahl and the crew of Kon Tiki on their famous voyage across the Pacific, and Henningsen later became a member of the Norwegian parliament. Together these men compiled an accurate description of the target area and secretly transmitted the information back to England.

LIEUTENANTS DONALD CAMERON AND GODFREY PLACE

There were several men who distinguished themselves throughout Operation Source, but the two officers who received most of the credit for the mission’s success were Lts. Don Cameron and Godfrey Place. Both men received the Victoria Cross for the actions against the Tirpitz.

Cameron, after serving a year with the merchant navy, joined the Royal Navy Reserve on 22 August 1939. He spent another year in general service and then on 19 August 1940 received orders to HMS Dolphin, the submarine school in Gosport, England. Upon completion of submarine training, he reported to HMS Sturgeon at Blyth, spending the next nine months conducting operations in the North Sea. In May 1941, a call for volunteers sent Cameron back to HMS Dolphin where he joined in the development of the first X-craft, eventually commanding X-6 during the attack on the Tirpitz.

Throughout Operation Source Cameron kept a personal diary that provides a chronological account of the training and actual mission. Cameron was exceedingly dedicated to the cause for which the X-craft were built and employed, and he worried that during the course of the mission he might somehow fail that cause. He wrote, “I have that just-before-the-battle-mother feeling. Wonder how they [the crew)] will bear up under fire for the first time, and how I will behave though not under fire for the first time … I can’t help thinking what the feelings of my next of kin will be if I make a hash of the thing.”

His close friend Comdr. Richard Compton-Hall later said, “Like all of us, he was afraid of the unknown and especially of possible failure, of letting people down, rather than of being afraid of the enemy.”

Cameron and his crew, Lt. W. S. Meeke and Chief E. R. A. Richardson, were caught during the operation and imprisoned in a German POW camp for the remainder of the war. Cameron was repatriated in May 1945 and was subsequently assigned to HMS Surf as additional lieutenant. Following duty on the Surf, Cameron was assigned to several other submarines before he received command of the HMS Tiptoe in May 1947. Three years later he returned to HMS Dolphin and in 1951 took command of another submarine, the HMS Trump. In 1955 Cameron returned to HMS Dolphin for the final time and was assigned as Commander, Submarines. Although Cameron served many tours after the war with the submarine service, he never fully recovered from his wartime internment. His health, which had been poor prior to Operation Source, deteriorated in the POW camps. He died unexpectedly in 1962.

Godfrey Place was graduated from the Royal Navy’s college at Dartmouth and commissioned in September 1938. He received posting to submarines after serving on the cruiser HMS Newcastle. His initial submarine training began at HMS Elfin and upon completion in 1941, he was assigned as the spare officer at Saint Angleo. Later in 1941, Place received orders to the Polish submarine Sokol out of Malta. Upon his departure from Sokol, Place was awarded the Polish Cross of Valor for combat service. After several short tours, Place joined the crew of the HMS Unbeaten in February 1942. While on combat patrol in the eastern Mediterranean, Place brought Unbeaten to periscope depth only to find a German submarine directly off his bow. He later recalled, “I called the Captain and we went to diving stations. I think it was something like 45 seconds from first sighting to firing the torpedo, under continuous wheel [constantly maneuvering] and in fact we got two hits.” German airplanes escorting the submarine converged on Unbeaten and began to pursue her. The submarine lay on the bottom for twenty-four hours before she escaped. Place was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for his actions.

In August 1942, he joined the 12th Submarine Flotilla and began training with the X-craft. One year later, as commander of X-7, he attacked and disabled the Tirpitz. Like Cameron, Place was captured during the action and was interned until May 1945. While in the POW camp, he was awarded the Victoria Cross. Upon his return to England, Place left submarines and went on to become a pilot in the fleet air arm of the Royal Navy. He had a distinguished military career, being promoted to rear admiral on 7 January 1968. He retired in 1970 and was made a Companion of the Bath (C.B.).