The major land route by which men, weapons, and supplies were moved from North Vietnam to South Vietnam. It ran through the Truong Son (Annamese Cordillera), the mountain range along the border between Vietnam and the “panhandle” of southern Laos. The trail was established by Group 559, named for the date of its creation (May 1959). Initially it ran down the eastern side of the Truong Son, crossing the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) directly and remaining within Vietnam. In 1961, it shifted to the west, detouring through Laos to bypass the DMZ. It was not a single trail, but rather a network.

For the first few years, it was a network of footpaths only, better suited to movement of troops than to the transportation of bulky cargoes. More than 40,000 men are said to have come down it by the end of 1963. There were of course no neatly defined dates for the shifts from foot traffic to bicycles (see photograph 16) and then to trucks, allowing larger quantities of munitions and supplies to be moved along it. Some portions of the trail were upgraded before others. But the key date for the decision to upgrade large sections of the trail to make them usable by trucks appears to have been 1964. Cargo being transported down the trail usually crossed from North Vietnam into Laos through the Nape Pass, the Mu Gia Pass, or the Ban Karai Pass, about 220, 115, and 55 kilometers, respectively, northwest of the DMZ. Troops coming down the trail often used crossing points closer to the DMZ. Construction of a gasoline pipeline running along the trail, allowing much more use of motor vehicles than had previously been possible, began in June 1968. The final link to create a continuous system of pipelines running from the Chinese border south as far as Military Region 7 (in III Corps, by the territorial units the United States used) was completed in December 1972.

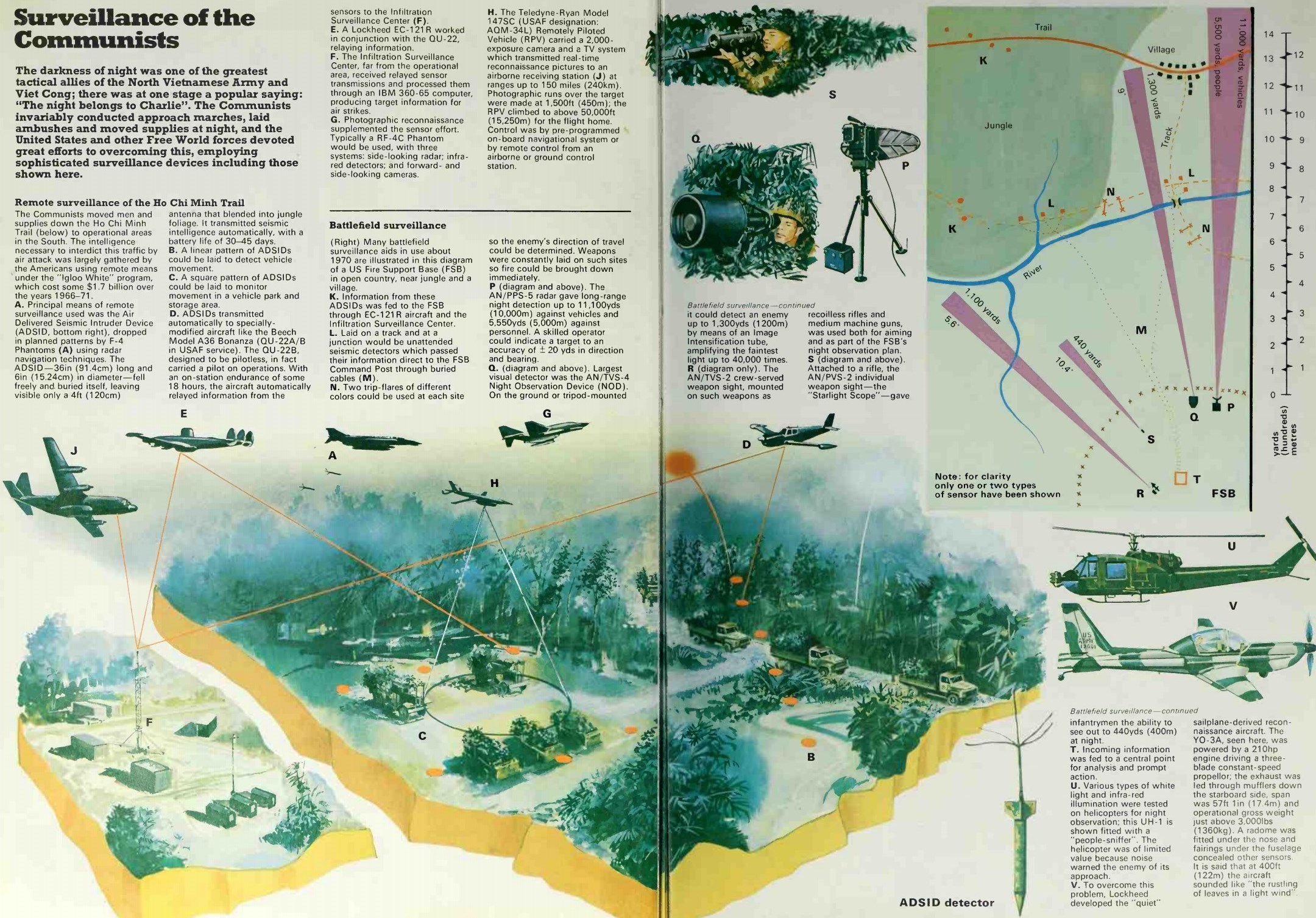

The most stunning failure was in the US bombing campaigns over the Ho Chi Minh Trail. They had little or no success in cutting off the Vietcong and North Vietnamese troops from their supply bases above the seventeenth parallel. In 1963 the Trail had been primitive, requiring a physically demanding, month-long march of eighteen-hour days to reach the south. But by the spring of 1964, the North Vietnamese put nearly 500,000 peasants to work full and part time and in one year built hundreds of miles of all-weather roads complete with underground fuel storage tanks, hospitals, and supply warehouses. They built ten separate roads for every main transportation route. By the time the war ended, the Ho Chi Minh Trail had 12,500 miles of excellent roads, complete with pontoon bridges that could be removed by day and reinstalled at night and miles of bamboo trellises covering the roads and hiding the trucks. As early as mid-1965 the North Vietnamese could move 5,000 men and 400 tons of supplies into South Vietnam every month. By mid-1967 more than 12,000 trucks were winding their way up and down the trail. By 1974 the North Vietnamese would even manage to build 3,125 miles of fuel pipelines down the trail to keep their army functioning in South Vietnam. Three of the pipelines came all the way out of Laos and deep into South Vietnam without being detected.

The Ho Chi Minh Trail had become a work of art maintained by 100,000 Vietnamese and Laotian workers. It included 12,000 miles of well-maintained trails, paved two-lane roads stretching from North Vietnam to Tchepone, just across the South Vietnamese border in Laos, and a four-inch fuel pipeline that reached all the way into the A Shau Valley.

The bombing was, to be sure, devastating. During the war the United States dropped one million tons of explosives on North Vietnam and 1.5 million tons on the Ho Chi Minh Trail. In 1967 the bombing raids killed or wounded 2,800 people in North Vietnam each month. The bombers destroyed every industrial, transportation, and communications facility built in North Vietnam since 1954, badly damaged three major cities and twelve provincial capitals, reduced agricultural output, and set the economy back a decade. Malnutrition was widespread in North Vietnam in 1967. But because North Vietnam was overwhelmingly agricultural-and subsistence agriculture at that-the bombing did not have the crushing economic effects it would have had on a centralized, industrial economy. The Soviet Union and China, moreover, gave North Vietnam a blank check, willingly replacing whatever the United States bombers had destroyed.

Weather and problems of distance also limited the air war. In 1967 the United States could keep about 300 aircraft over North Vietnam or Laos for thirty minutes or so each day. But torrential rains, thick cloud cover, and heavy fogs hampered the bombing. Trucks from North Vietnam could move when the aircraft from the carriers in the South China Sea could not.

Throughout the war North Vietnam, assisted by tens of thousands of Chinese troops from the People’s Liberation Army, gradually erected the most elaborate air defense system in the history of the world. They built 200 Soviet SA-2 surface-to-air missile sites, trained pilots to fly MiG-17s and MiG-21s, deployed 7,000 antiaircraft batteries, and distributed automatic and semiautomatic weapons to millions of people with instructions to shoot at American aircraft. The North Vietnamese air defense system hampered the air war in three ways. American pilots had to fly at higher altitudes, and that reduced their accuracy. They were busy dodging missiles, which consumed the moment they had to spend over their target and reduced the effectiveness of each sortie. And they had to spend much of their time firing at missile installations and antiaircraft guns instead of supply lines.

The CIA estimated that between 1966 and 1971 North Vietnam had shipped 630,000 soldiers, 100,000 tons of food, 400,000 weapons, and 50,000 tons of ammunition into South Vietnam along the Ho Chi Minh Trail. Abrams wanted to invade Laos, cut the Ho Chi Minh Trail, and starve the North Vietnamese troops waiting in South Vietnam. But because the Cooper-Church Amendment prohibited the use of American troops outside South Vietnam, Abrams would have to rely on ARVN soldiers. During Nixon’s first two years in office, nearly 15,000 American troops were killed in action. Figures on cargo have been inconsistent.

A total figure of 1,500,000 tons had been given as the amount of cargo transported on the trail, but it has also been suggested that only a little more than 500,000 tons was actually delivered to destinations in South Vietnam.

GROUP 559. This PAVN unit, also called the Truong Son troops, was responsible for creating and operating the Ho Chi Minh Trail, the route by which men, weapons, and supplies were sent from North Vietnam through southeastern Laos to South Vietnam. It was established on May 19, 1959, and began operations immediately. It was commanded by Vo Bam from its origin to 1965, by Phan Trong Tue from April to December 1965, by Hoang Van Thai (not the Hoang Van Thai who had been PAVN chief of staff during the First Indochina War, but another general of the same name) from December 1965 to 1967, and by Dong Si Nguyen from 1967 to 1975. It is said to have carried more than 1,000,000 tons of cargo, of which more than 500,000 tons were delivered to South Vietnam.

GROUP 759. This was the unit that shipped weapons and ammunition from North Vietnam to South Vietnam by sea, in substantial steel-hulled trawlers. A preliminary organization-a group of staff officers assigned to study the feasibility of such operations-was set up in July 1959; Group 759 was established as an operational unit on October 23, 1961. The first success, in which the ship Phuong Dong 1 delivered 28 tons of cargo to Ca Mau (the southernmost tip of South Vietnam, presumably chosen because it was the place where the Republic of Vietnam would least expect to find North Vietnamese vessels approaching the coast), was in September or October of 1962. By February 1963, there had been three more deliveries, of about 30 tons each, to the same area. Vessels with capacities of 50 to 60 tons made numerous deliveries during 1963; vessels with capacities up to 100 tons came into use before the end of 1964. Group 759 was redesignated Group 125 on January 24, 1964. By February 1965, a total of almost 5,000 tons had been delivered in 88 voyages, mostly to Nam Bo.

Security was excellent for more than two years. Many senior U. S. naval officers refused to believe the rumors that the Viet Cong were receiving significant munitions shipments by sea until Vessel 143 was spotted by aircraft and sunk at Vung Ro, on the coast of Phu Yen province, on February 16, 1965. After this incident, the United States and the Republic of Vietnam greatly expanded their efforts to patrol the coast of South Vietnam. Group 125 continued its efforts to deliver munitions to South Vietnam, but these efforts became far more difficult and dangerous.