At the outbreak of the War of 1812, the artillery of the Regular Army consisted of the Regiment of Artillerists and the Regiment of Light Artillery. The former unit was organized into five battalions of four companies each, all serving as foot artillery or infantry. The Light Artillery Regiment included ten companies, all serving as infantry. To meet the needs of the expanding wartime army, Congress on January 11, 1812, authorized the establishment of the 2nd and 3rd artillery regiments, each with two ten-company battalions. The Regiment of Artillerists was redesignated the 1st Regiment. Captain George Izard of the Regiment of Artillerists was ap¬ pointed colonel of the 2nd Artillery; Captain Winfield Scott of the Light Artillery was named its lieutenant colonel. Scott later commanded the 2nd Regiment of Artillery from March 1813 until his promotion to brigadier general on March 8, 1814.

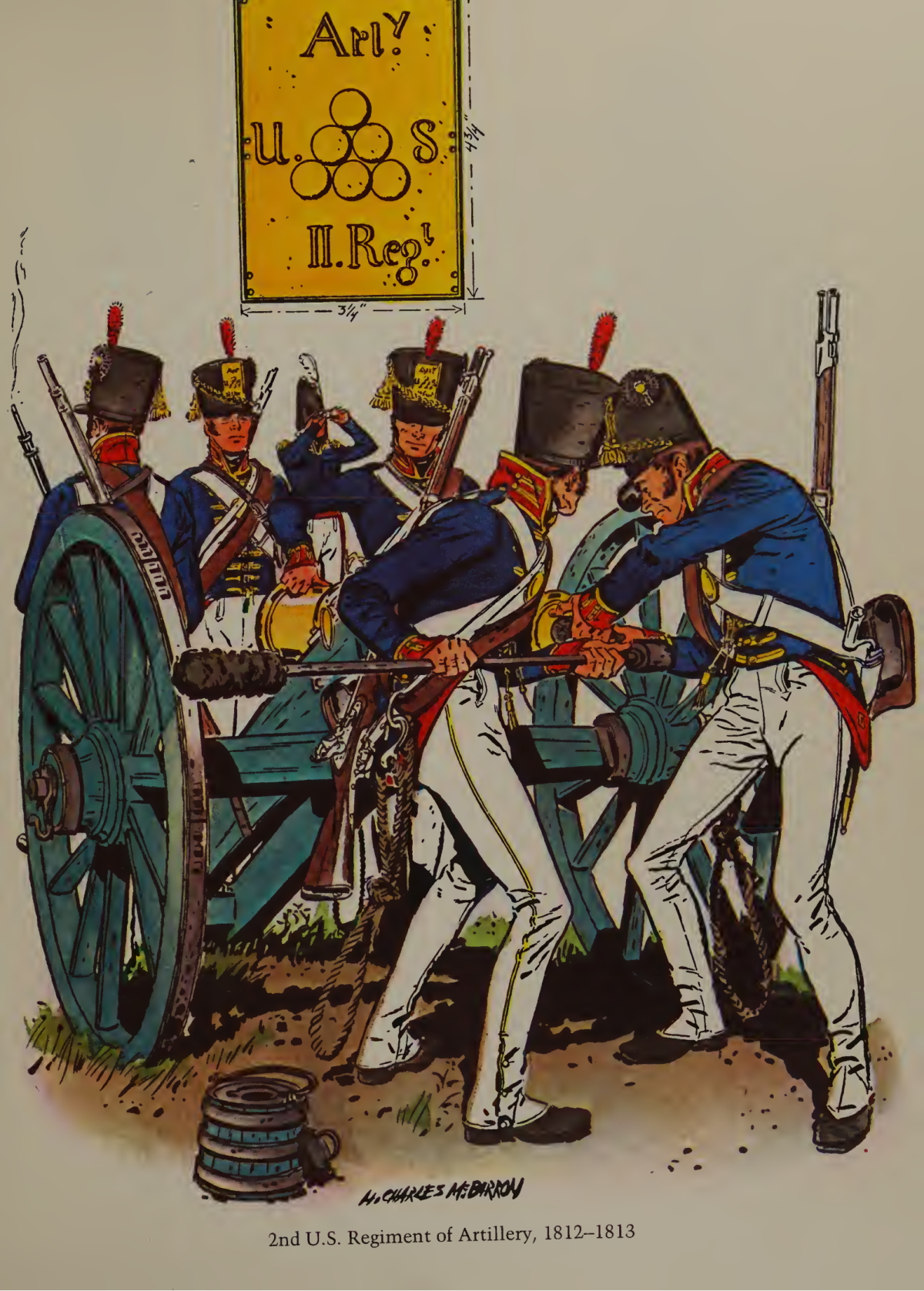

The dress of the three foot artillery regiments was specified early in 1812. This uniform, with its chapeau bras and long-tailed coat, was worn by the 1st Regiment, which continued to call itself the Regiment of Artillerists until well into 1813. The two new regiments, however, were required to accept the light artillery felt cap, with the infantry-type band and tassel in yellow cord, in place of the chapeau bras.

The artillerymen in this plate are shown with their coattails shortened, as authorized late in 1812. They still wear yellow welts, or cording, on their overalls, although this feature and the gaitered effect at the ankles were both abolished that same year. Undoubtedly, the uniforms worn by companies in the new regiments varied greatly because of clothing shortages and supply problems. The cap plate illustrated is one of several excavated in the northeast bastion of Fort Erie, which was blown up during the British attack on August 14, 1814.

The gun crew shown here is loading the piece. The matross at the far left holds a lighted portfire; he will use it when ordered to fire the gun. Next is the 1st cannoneer: once the gun is loaded, he will thrust a steel pick through its vent to pierce the powder bag and then insert a priming tube. That completed, he will lay the gun on a target designated by the officer standing behind him. The 2nd cannoneer is “thumbing the vent”-keeping it closed with his thumb while the gun is sponged and loaded, to prevent a premature discharge. As soon as the matross on the far right has finished inserting the cartridge into the mouth of the gun, he will assist the matross holding the rammer staff in ramming the cartridge home. The other members of the crew are not shown; they would be engaged in bringing ammunition to the gun or in shifting the gun’s trail, as directed by the 1st cannoneer, to help him lay the gun on target.

The matrosses wear bricoles, shoulder straps of heavy leather, with attached drag ropes, which have been looped up out of the way. The combination made a man harness, used in manhandling guns into position or in helping the gun teams drag them across difficult ground. Each man carries a musket, the first type of the Model 1812, slung over his left shoulder. In a more stabilized position, the muskets would have been stacked to the rear of the gun. There is no indication that these artillerymen carried swords, as did their successors of a later period.

The gun shown is a bronze 12-pounder field piece. Its carriage has been painted in the color used by the French artillery of this time, since the 1812 correspondence of Colonel Decius Wadsworth, the newly appointed Chief of Ordnance, indicated that French carriages were being used as models for those he was having manufactured.

The lot of the foot artilleryman of this period was not an easy one. Field repairs were made by the artillerymen themselves. Manuals of the period provided detailed specifications for replacing damaged parts of the carriage and even for the manufacture of its parts. A good many companies were employed largely as infantry throughout the war. However, despite a lack of experience, the American artillery performed well. Elements of the 2nd Regiment saw action at the capture of Fort George, the battles at Fort Erie and Stony Creek and in many other minor engagements.

The U. S. Army in 1812

Whether the United States could fulfill its high expectations depended less on lofty aspirations than on the actual strength of its military forces, and here there were reasons for concern. In 1811, the U. S. Army consisted of a small corps of engineers; seven infantry regiments; and one regiment each of rifles, dragoons, artillery, and light artillery. The light artillery regiment was to be a mobile formation, but as a cost-saving measure, the government had sold its horses in 1808. The rest of the Army also suffered from a chronic manpower shortage, having just fifty-five hundred men under arms with another forty-five hundred positions vacant.

As the prospect for war grew imminent, Congress enacted several expansions. By June 1812, the authorized strength of the Army had grown to 35,603 men organized into twenty-five regiments of infantry, four of artillery (including the now remounted regiment of light artillery), two of dragoons, the rifle regiment, six companies of rangers, and various engineer and ordnance troops. In actuality, only 6,744 soldiers were on active service, scattered mostly in small detachments along the extensive frontier at such places as Fort Mackinac, on a small island at the straits of Lakes Michigan and Huron; Fort Dearborn, near present-day Chicago; and at trading centers such as Fort Osage, Missouri Territory, and Fort Hawkins, Georgia. In order to fill the ranks, the government offered a signing bonus of $16 for a five-year term of service, but few were willing to enlist for such a long time. Desperate to attract recruits, Congress reduced the length of service, added more financial incentives, and banned the practice of flogging. Despite all of these measures, the government failed to bring the desired number of men into the Regular Army.

One of the reasons that the Regular Army failed to draw recruits was that many men preferred the shorter enlistments and the attractive financial incentives offered by their home state militias. The War Department estimated that 719,449 militiamen were available for active service. In the spring of 1812, Congress authorized the president to ask the states to provide 30,000 federal volunteers for one-year’s service drawn from their militias. It also permitted the president to call on the states to mobilize as many as 100,000 militiamen for up to six months of federal service. The numbers were impressive but deceiving, for most of the militia was poorly trained and equipped. Militia leadership was equally haphazard, with many state officers owing their rank to social status, political patronage, or popularity, as some units elected their officers. In short, the militia was a weak foundation upon which to base a national mobilization.

Issues of regionalism and politics also affected mobilization. The strongest support for the war came from those areas with the fewest resources to sustain it, namely, the South and the West. States in the Northeast were better situated for the conflict, but their support was less than wholehearted. When Republican President Madison issued his call for militia, several of the New England states, where the Federalist Party was strong, refused to supply troops on the grounds that Madison’s intended purpose did not meet the missions authorized in Article 1, Section 8, of the United States Constitution “to execute the Laws of the Union, suppress insurrections, and repel invasions.” Some state courts ruled that the federal government did not have the authority to require militia to cross international borders to fight outside the United States, reserving that decision exclusively to the commander of a state’s militia. As a result of these legal challenges, the federal government would experience difficulty in raising militia forces from the Northeast throughout much of the war.

Getting men into the ranks was only the start of the government’s problems. Feeding, equipping, training, and moving the Army like- wise posed daunting obstacles, particularly given the rudimentary transportation network that existed along the frontier with Canada. Nor did the Army have the bureaucratic infrastructure to wrestle with the burgeoning issues of mobilizing and sustaining a wartime force. In 1812, the entire War Department consisted of Secretary of War William Eustis and eight clerks. Eustis had been a surgeon during the Revolutionary War and was later elected to the House of Representatives. President Thomas Jefferson had ap- pointed him secretary of war in 1809 because he was a staunch member of the Republican Party. His military and bureaucratic skills were limited.

In March 1812, Congress attempted to rectify some of the Army’s administrative deficiencies by establishing the positions of quartermaster general and commissary general of purchases. Then in May, the legislature created an Ordnance Department to develop weapons and equipment and to address the deplorable condition of military stores. As many as one in five of the Army’s weapons were inoperable, and much of its ammunition had been procured in 1795. Shortages of everything from tents and shoes to medicine and other items likewise existed. Unfortunately, without central direction, the quartermaster general, commissary general, chief of ordnance, and various contractors would often compete for the same resources, adding further chaos to the Army’s primitive logistical system.

The Army’s senior officer in 1812, Maj. Gen. Henry Dearborn, had a stellar record of service during the Revolutionary War, serving in all major battles in the northern theater, including Bunker Hill, Saratoga, Monmouth, and Yorktown. He had aligned himself with the Republican Party, and when Jefferson had become president in 1801, he had appointed Dearborn as secretary of war. Dearborn, who had served in that office until Eustis replaced him in March 1809, had been thoroughly involved during his tenure with reducing Army force structure under Jefferson’s Military Peace Establishment Act of 1802. Although considered the nominal commander of the U. S. Army, Dearborn lacked the statutory authority and the staff to fully oversee Army operations, and, like Eustis, he was overwhelmed by the crush of responsibilities incumbent with mobilizing and guiding the national war effort.

As for the officer corps, it was as unprepared for what lay ahead as the rest of American military establishment. If most militia and volunteer officers were rank amateurs who owed their posts to their political and social connections, then the officers of the Regular Army were not much better. The nation’s small Regular Army was a back-water in American society that did not necessarily attract the finest talent, while the Jefferson and Madison administrations had often applied a political litmus test in selecting officers. A glimmer of professionalism existed among a few individuals, but these were the exceptions to the rule. Perhaps the Army’s best hope for the future, the U. S. Military Academy at West Point, New York, was by 1812 barely ten years old and had produced just 120 graduates, of whom 99 would serve in the war, mostly in junior positions. As for the rest, one of the nation’s more gifted military leaders, Lt. Col. Winfield Scott, claimed that the older officers had “very generally sunk into either sloth, ignorance, or habits of intemperate drinking,” while the new officers were for the most part “course and ignorant men . . . swaggerers . . . decayed gentlemen, and others-`fit for nothing else,’ which always turned out utterly unfit for any military purpose whatever.”