The fourteenth century should have belonged to the Habsburgs. Across Central Europe, the lines of kings and princes faltered. In 1301, the Hungarian Árpád line came to an end; five years later, the Bohemian Přemyslids expired, to whose house Ottokar II had belonged. Then, in 1320, the last of the Ascanian margraves of Brandenburg died. But the Habsburgs did not benefit from the biological misfortune of others. Instead, over the fourteenth century they themselves were squeezed out of office and eminence in the Holy Roman Empire. For the time being at least, the future seemed to belong to the Wittelsbach rulers of Bavaria and the new Luxembourg kings of Bohemia.

On his death in 1291, Rudolf was buried in the crypt of Speyer Cathedral beside the tombs of previous emperors of the imperial Staufen dynasty. But the electors were determined that the Habsburgs should not take the Staufens’ place and treat the Holy Roman Empire as if it was a family possession. So they initially conspired to prevent Rudolf’s son and heir, Albert (1255–1308), from succeeding. Nonetheless, Albert skilfully ensured the election by a handful of princes of a puppet candidate, Conrad of Teck. Within forty-eight hours of his election, Conrad was dead, his skull cleft open by a nameless assassin. Conrad’s and Albert’s rival, Adolf of Nassau, now became king. The majority of electors backed Adolf precisely because he had no lands of his own and so was no threat, but once in office Adolf sought to grab what he could. The electors turned to Albert for help, who defeated and killed Adolf. In return, they elected Albert king in 1298.

King Albert I has been badly treated by historians, who have too readily embraced the propaganda of his enemies—that he was ‘a boorish man, with only one eye and a look that made you sick … a miser who kept his money to himself and gave nothing to the empire except for children, of which he had many.’ Certainly, Albert lacked an eye. In 1295, his physicians had mistaken an illness for poisoning and to expel the imagined fluid they had suspended him upside-down from the ceiling. The consequent compression to the skull had robbed him of an eyeball. Albert was a prolific father too, siring no less than twenty-one children, of whom eleven made it past childhood. Their consequent marriages into the royal and princely houses of France, Aragon, Hungary, Poland, Bohemia, Savoy, and Lorraine indicate the prestige that now attached to Albert and to the family of which he was head.

Like his father, Albert endeavoured to be crowned emperor in Rome. Pope Boniface VIII received Albert’s embassy haughtily, declaring the imperial title to be his to give or withhold. Seated on the throne of St Peter, his head weighed down by the massive papal tiara of St Sylvester, with its 220 precious jewels set in gold, Pope Boniface boasted, ‘I am the King of the Romans, I am Emperor.’ But it was not the pope but instead a family dispute that brought Albert down. King Rudolf had promised his younger son, Rudolf, an inheritance equal to Albert’s, but had not made good his vow. The younger Rudolf’s heir, John, smarted under the jibe of ‘Duke Lackland’ and pressed to be given a share of the Habsburg patrimony, but Albert preferred to bestow titles and wealth upon his own children. On May Day 1308, John, along with several knights, ambushed Albert and slew him. The murder was a pointless act that brought John lifelong incarceration in a monastery in Pisa and the label of ‘the Parricide.’

Upon Albert’s death, the electors chose Henry of Luxembourg for the same reason that they had a decade before elected Adolf of Nassau—to forestall a Habsburg succession by choosing a ruler who was insufficiently powerful to threaten their own interests. But like Adolf, Henry immediately set about constructing his own power base, in this case by taking the Bohemian crown. In 1312, Henry even travelled to Rome, to be crowned emperor there by the pope, which was the first time in almost a century that a king had done so. He died the next year from malaria contracted on the journey. By this time, German chroniclers were so used to having their rulers killed that they reported Henry to have been murdered at the pope’s instruction with poisoned communion wine.

Gathering at Frankfurt in 1314, the electors feared to appoint Henry’s son, the startlingly courageous John of Luxembourg. Instead, the electors split their vote between Albert’s son, Frederick the Fair of Habsburg (lived 1289–1330), and the Wittelsbach Duke Louis of Bavaria. For ten years the two men were at war, each claiming the royal title. Frederick the Fair’s fate was impoverishment, defeat, imprisonment, a disadvantageous settlement, and an early death in 1330 in the lonely fastness of Burg Gutenstein, west of Wiener Neustadt. Frederick’s two brothers hurried to make peace with Louis, acknowledging him as the lawful king. By this time, the decline of the Habsburgs was palpable. Whereas a generation before, they had married into the royal houses of Europe, they were now reduced to seeking spouses from a humbler stock of obscure Polish dukes and minor French nobles.

Emblematic too of the Habsburgs’ declining fortunes was their defeat by the Swiss. The Swiss forest cantons of Uri, Schwyz, and Unterwalden had united in 1291 to form a defensive alliance, but it had rapidly become an offensive one, aimed against the Habsburgs. This was mostly due to Habsburg expansion into the Alpine valleys, where the family had taken over territories, toll stations, and rights of lordship following their acquisition of the Kiburg lands. As part of his struggle with Frederick the Fair, King Louis brought the cantons onto his side. At the end of 1315, when Frederick’s brother Leopold marched into the valleys to assert his rights, he was ambushed and defeated by the men of Uri and Schwyz. The battle of Morgarten was the first major engagement in which the Swiss deployed the lethal pole-and-axe halberd against cavalrymen, using its hooked blade to drag the enemy’s knights from their mounts and its spiked tip to skewer them. The halberd remains the ceremonial weapon of choice for today’s Pontifical Swiss Guard in the Vatican.

The final blow to Habsburg prestige came in 1356. In that year King Louis’s successor, Charles IV of Luxembourg, who had just been crowned emperor in Rome, published his so-called Golden Bull (named on account of its hanging gold seal or bulla). The Golden Bull contained a new scheme for the election of the ruler, which fastened down the identity of the seven electors—the three archbishops of the Rhineland and four secular lords, who held the office henceforth by right of inheritance. Even though they had participated on several occasions in electing kings, the Habsburgs were omitted from the new college of electors, thus writing them out of the most important constitutional document in the history of the Holy Roman Empire. In the seating plan that he separately drew up for future meetings of the diet, Charles made clear their diminished status, placing the Habsburgs in the second row, behind the electors, senior clergy, and high dignitaries of the empire. The Habsburg response was ideologically devastating and would change forever the way they thought about themselves and their historical role. To counter Charles IV’s insult, they jettisoned their Swabian past and became instead Austrians and Romans.

For the first fifty years of their rule as dukes of Austria, the Habsburgs had regarded the duchy as secondary in importance to their traditional heartland in Swabia. They had milked Austria to fund the defence of their other territories, and they had used it as a starting place for campaigns into Bohemia, which they regarded as the greater prize. It was only after 1330, when Frederick the Fair’s brother, the arthritic Albert the Lame (lived 1298–1358), assumed headship of the family, that the Habsburgs showed any sustained interest in Austria. Since the Swiss continued to press against the Habsburg lands and strongholds in the Aargau, Albert moved his court to Vienna’s Old Fort, in the heart of what has become the Hofburg Palace. Albert also began the construction of a family mausoleum at Gaming in Lower Austria, and he repossessed Carinthia and Carniola, which his grandfather had pawned. Albert’s prolonged stays in Austria earned the Habsburgs the description from one chronicler of ‘the Austrians’, the first time the term was used in this way. Whereas in the past, the Habsburgs had administered Austria through regents, it was now their Swabian possessions that had governors appointed to them.

The Habsburgs may not at first have known what to do with Austria, but Austria knew what to do with the Habsburgs. Originally a borderland called the ‘eastern realm’ (Ostarrîchi—the name first appears in 996), its earliest rulers belonged to the Babenberg family. The Babenbergs aspired to greatness, marrying into the lines of both Holy Roman and Byzantine emperors, on which account they thought of themselves as trustees of the inheritance of Rome. Their conspicuous dedication to the faith was marked by the founding of a dense network of monasteries, in return for which generations of monks wrote their praises. The reputation of the Babenbergs is shown in the soubriquets by which they were recalled—the Illustrious, the Devout, the Glorious, the Strong, and the Holy. Only the last of the Babenberg line, Frederick II (died 1246), had the unhappier nickname of ‘the Quarrelsome.’

Genealogies of the Babenbergs sometimes included quaint descriptions of the countryside and its cities. Little by little, however, a belief in the exceptionalism of the ruling family fused with the conviction that the land and its people were special. A literary tradition arose, which saw the Austrians as descendants of the Goths of classical antiquity, or which proposed an even more illustrious descent from Greek and Roman heroes. The old Roman name for Austria, Noricum, invited the possibility that Austria was founded by Norix, the son of Hercules, who, coming from the lands about Armenia, had invested his heirs with Austria and Bavaria respectively. The Babenberg lands were also home to the Nibelunglied epic, which in its early versions coupled stories taken from Germanic mythology with episodes in the ruling dynasty’s history.

The Habsburgs consumed all of this, adding to the Babenbergs’ religious foundations at Heiligenkreuz and Tulln and enlisting chroniclers and poets to proclaim their own piety. Gradually, the history of the Babenbergs and Habsburgs merged into one, so that the Babenbergs became ancestors to the Habsburgs, in token of which the Habsburgs frequently adopted the Babenberg baptismal name of Leopold. This was important since it harked back to the Babenberg Leopold III, who although not yet a saint had posthumously performed enough miracles to qualify as one. At a time when saintliness added lustre to a family, the Habsburgs were otherwise short of suitable forebears.

The Habsburgs were also swift to discover Roman credentials of their own, promoting their supposed descent from the allegedly senatorial family of Colonna. Chroniclers added to the story, describing how two brothers exiled from ancient Rome had gone north of the Alps, one of whom went on to found Castle Habsburg. Even more imaginatively, the author of the Königsfelden Chronicle interwove his account of the Habsburgs with a Roman inheritance, saintliness, and prophecy. Having enumerated the line of Roman emperors from Augustus to Frederick II, he went on to tell the life of King Rudolf of Habsburg. He then related the biography of Rudolf’s granddaughter Agnes, who after a short time as queen of Hungary had forsaken the world to live next to Königsfelden Abbey, near Brugg. First of all, however, the chronicler rehearsed an old tale of the discovery in Spain of a huge book concealed in a stone, with pages of wood on which was written in Latin, Greek, and Hebrew the entire history of the world, including the time to come and the Last Judgement. The implication was clear—made holy by the devotions of Agnes, the Habsburgs were both destined and foretold to rule as Roman emperors.

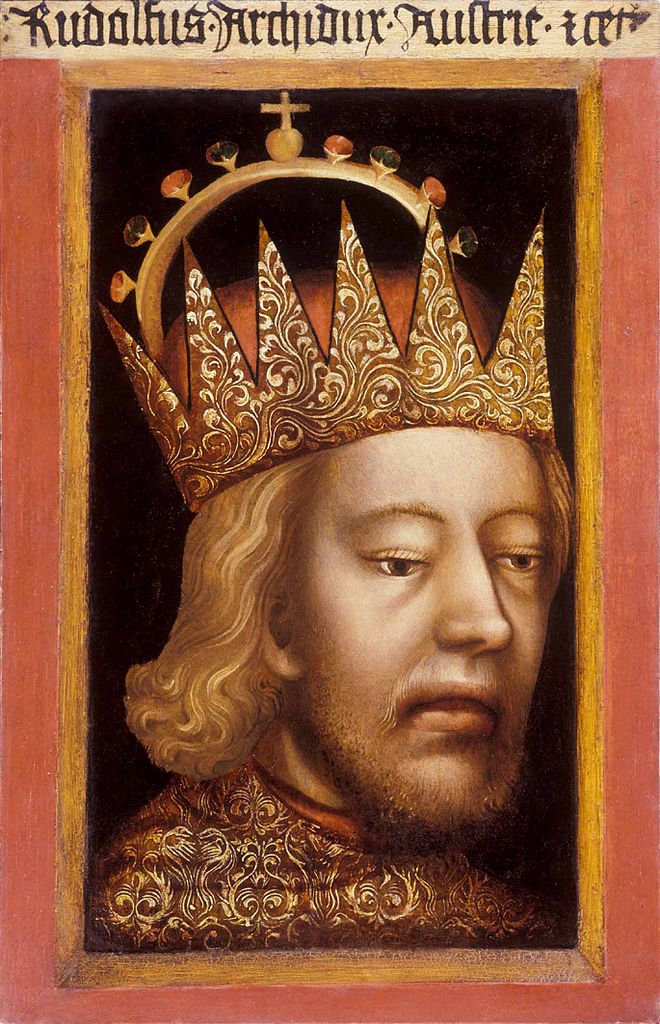

The first half-frontal portrait of the Occident. It had been on display above Rudolf’s grave in the Stephansdom of Vienna for several decades after his death, but can now be seen in the Museum of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Vienna. Apart from the (invented) archducal crown, the foreshortening of which the artist did not completely master, the portrait is completely realistic. Even the duke’s incipient facial palsy is shown.

Exceptionalism was in the 1350s transformed into a political programme. Offended and diminished by Charles IV’s Golden Bull, Rudolf of Habsburg (lived 1339–1365) was intent upon both restoring his family’s prestige and welding together a territorial state which outstripped its rivals. He did so with an energy, pace, and imagination that belied his youth and confounded his rivals. Within a few months of the death of his father, Albert the Lame, in 1358, the young Rudolf instructed his scribes to confect five fraudulent charters. Their purpose was to establish the Habsburgs as leading princes in the Holy Roman Empire by melding the Habsburg inheritance with Austria and Rome. Rudolf’s was the most ambitious work of forgery in medieval Europe since the eighth-century Donation of Constantine, which had appointed the pope as the ultimate ruler of Christendom. It was also rather better done.

Of the five charters, three were confirmations of the others, thus textually interlocking the whole deception. The substance of the forgery lay with the first two charters, which are known as the ‘Pseudo-Henry’ and the ‘Greater Privilege.’ The author of the Pseudo-Henry, who was probably Rudolf’s chancellor, pretended that it was a charter issued by Emperor Henry IV in 1054, drawn up to record the contents of two letters in the keeping of Duke Ernest of Babenberg. The first letter was supposedly addressed by Julius Caesar to the people of the ‘eastern land’, by which was plainly meant Austria. Julius Caesar ordered the easterners or Austrians to accept his uncle as their ruler, who was given an absolute power over them as their ‘feudal lord.’ The fake letter also admitted Julius Caesar’s uncle to the innermost counsels of the Roman Empire, ‘so that henceforth no weighty matter or suit be resolved without his knowledge.’ In the other letter contained in the Pseudo-Henry, the emperor Nero similarly addressed the people of the east. Nero declared that because they outstripped in splendour all other peoples of the Roman Empire, he had upon the advice of the senate released them from paying all imperial taxes and awarded them freedom for ever more.

In contrast to the Pseudo-Henry, the Greater Privilege was at least partly authentic, being based upon the text of the charter given by Frederick I Barbarossa in 1156, which had elevated Austria to a duchy. Much, however, was added to the original text. Austria was now acknowledged as the ‘shield and heart’ of the Holy Roman Empire, by virtue of which its duke had full rights within the duchy. The duke was given the title of ‘palatine archduke’, which brought with it a special crown and sceptre and the right to sit at the emperor’s right hand, equal in precedence to the imperial electors. To strengthen the duke’s dominion, he was permitted to pass on the duchy intact to his eldest son and, in the absence of sons, to a daughter. The concocted version was known to posterity as the ‘Greater Privilege’ to distinguish it from the genuine privilege of 1156, which was subsequently called the ‘Lesser Privilege.’

The other three charters which confirmed the Pseudo-Henry and the Greater Privilege added some more points. In formal processions, the archduke, as he had become, and his retinue were always to have first place, and it was permitted that the archducal crown include the fillet or headband of majesty, normally worn by kings beneath their crown. The archbishop of Salzburg and the bishop of Passau, both of whom had jurisdiction over Austria in church matters, were made subject to the archduke. Like the charters that they confirmed, these secondary instruments indicate that Rudolf was not, as is often alleged, moved only by resentment of Charles IV’s Golden Bull of 1356 and so primarily bent on scoring points. With its stress on the archduke’s complete power in Austria, the subordination of the church to him, and the complete inheritability of his office, the forgeries were as much intended to advance the power of the archduke in his own lands as to influence etiquette in the imperial court and the archduke’s own headwear.

The Pseudo-Henry with its letters of Julius Caesar and Nero was almost immediately denounced. The Italian scholar Petrarch wrote to Emperor Charles IV in 1361, highlighting anachronisms in the text and dismissing it as ‘vacuous, bombastic, devoid of truth, conceived by someone unknown but beyond doubt not a man of letters … not only risible but stomach-churning.’ The Greater Privilege, however, fared rather better. Invoked to justify the succession of Maria Theresa to Austria on the death of her father Charles VI in 1740, it was proved to be a forgery only in the mid-nineteenth century. The Donation of Constantine, by contrast, was exposed as fraudulent in the fifteenth century.

In 1360, Rudolf presented the five false charters to Emperor Charles IV for confirmation, interspersing them with seven genuine documents. Charles quibbled over some details, but grudgingly confirmed the whole package, ‘insofar as its provisions be lawful.’ He did not, however, alter the composition of the college of electors or seating arrangements at the diet to accommodate Rudolf’s pretensions. Nevertheless, Rudolf now used the title of archduke and sported the archducal crown he had devised. After some hesitation, both the crown and, more slowly, the title became the style of his successors and, by no later than the mid-fifteenth century, of all senior members of the Habsburg family.

The duchy of Austria, along with the neighbouring duchies of Styria, Carinthia, and Carniola, constituted not so much a defined territory as a bundle of rights. Some properties belonged to the archduke, but others were held independently of him as lands bestowed separately by the monarch. The Greater Privilege had proclaimed the archduke’s absolute authority within Austria, and Rudolf now sought to make good his claims. All lands held of the monarch were transformed into lands that belonged to him, which he alone had the right to distribute. One of the largest holders of imperial lands in Carinthia was the patriarch of Aquileia, whose grand title was a relic of the sixth century, hardly matching the patriarchate’s now puny power. When the patriarch proved obdurate, Rudolf invaded his lands and forced his submission. Even though Alsace had nothing to do with the Greater Privilege, Rudolf extended the same principle there, declaring that his rank meant that he was not the subject but rather ‘the master of all rights and freedoms.’

The archbishop of Salzburg and the bishop of Passau proved harder nuts to crack, for neither was ready to shrink his diocese by giving way to Rudolf’s plan for an Austrian bishopric based in Vienna. Rudolf proceeded, nonetheless, to rebuild St Stephen’s in Vienna as if it were a cathedral rather than just a parish church, replacing the Romanesque nave with a massive Gothic one and planning the construction of two towers (only one was ever built). He gave the church its own chapter of canons, to which it was not entitled since it had no bishop, and he decked the canons out as cardinals, giving them scarlet birettas and gold pectoral crosses. The refashioned church was also intended to celebrate the Habsburg family, so Rudolf placed statues of himself and his forebears around the nave and made the crypt into a mausoleum for his descendants. Beside the church, Rudolf set up a university, which was intended to rival Charles IV’s foundation in Prague. By virtue of his rebuilding of St Stephen’s, Rudolf is known to posterity as ‘the Founder.’ He chose the soubriquet himself and had it carved in magic runes upon his sarcophagus in the north choir of the church.

In the art of deception, Rudolf found an equal. The county of the Tyrol was wealthy from its gold and silver mines and from the tolls of the roads that linked Italy to the German cities on the other side of the Brenner Pass. The Tyrol was held in the early 1360s by the widow Margaret, whose nickname of Maultasch (‘Big Mouth’) is the kindest in a long list of epithets. Previously married to a Luxembourg and then to a Wittelsbach prince, she lost her only surviving son at the beginning of 1363. Tyrol was there for the taking, and there was no lack of contenders. But Margaret was not easy prey. She had physically kicked out her first husband, not bothered with a divorce before marrying her second, put up with excommunication, and tyrannized both her new spouse and her recently deceased son.

Margaret did a deal with Rudolf. In return for allowing her to keep the county during her lifetime, she promised to assign the Tyrol to him in advance. But her ministers, who were also the county’s principal landowners, forced her in January 1363 to agree that all treaties with foreign princes required their consent. Margaret attempted to win them round with gifts of land and other inducements, but without success. Even Rudolf’s personal appearance in the Tyrolean capital of Innsbruck made no difference. To convince the ministers, Margaret and Rudolf concocted together a fake charter. The forgery showed that four years previously Margaret had promised to assign the Tyrol to Rudolf in a solemn deed that could not be retracted. Even though the forged charter used the wrong seal, it was believed. With the January agreement ostensibly voided, Margaret’s ministers gave way, recording their consent in a letter to which they appended their own fourteen seals. By the end of the year, Rudolf had convinced Margaret to abdicate, offering her a wealthy retirement in Vienna. The Tyrol was now his. On the back of the Tyrol later came the county of Gorizia (Görz-Gradisca) on the Adriatic, which belonged to a distant line of Margaret’s family that eventually expired in 1500.

Rudolf died in 1368, at the age of just twenty-five. Since it was high summer and his corpse was decomposing fast, it was boiled to remove the flesh. But his bones were put in the crypt of St Stephen’s and not, as he had planned, in the sarcophagus in the choir. The empty tomb with its runes and life-size effigy of Rudolf wearing the archducal crown stands in some ways as a metaphor for his reign—bombastic and self-promoting, but also hollow. In his lifetime, Rudolf failed to obtain the reputation for himself and the eminence for Austria that he worked and forged for. He won neither the bishopric he wanted nor recognition as the equivalent to an elector. His university, still today named in his honour, comprised just several rooms in a school. It would be his brother who recruited the professors and gave the university proper accommodation. Obtained through subterfuge, the Tyrol was his principal acquisition.

Rudolf’s achievement was, however, a more subtle one. By giving the Habsburgs a historical consciousness and set of beliefs about themselves, Rudolf made them more than just a group of blood relatives. The imagined Roman and Austrian past, with the invented archducal crown and title, inspired a sense of solidarity and purpose among his successors that became more embedded with the passage of each generation. Others might hold the rank of elector by virtue of a modern emperor’s gift, but the Habsburgs owed their eminence to Julius Caesar and to privileges confirmed by successive emperors over the centuries. Even in death, the family was united in the new mausoleum built in St Stephen’s crypt. In the making of the Habsburgs as a dynasty, Rudolf was indeed, as the cryptic message on his empty tomb proclaimed, ‘the founder.’