On April 3, Emperor Hirohito, dissatisfied with what was happening on Okinawa, had directed the Thirty-Second Army to mount a counteroffensive and drive the Americans into the sea, or to make a counter-landing that would dramatically alter the strategic situation.

Hirohito might have seemed a remote demigod to most of his subjects, but he in fact was deeply involved in military matters. On the second day of the Allied invasion of Okinawa, the emperor worried aloud that “if this battle turns out badly, the army and navy would lose the trust of the nation.” By the third day, Hirohito could no longer simply watch from the sidelines. When the emperor’s order to counterattack reached General Ushijima, he could only obey. “All of our troops will attempt to rush forward and wipe out the ugly enemy,” Ushijima replied.

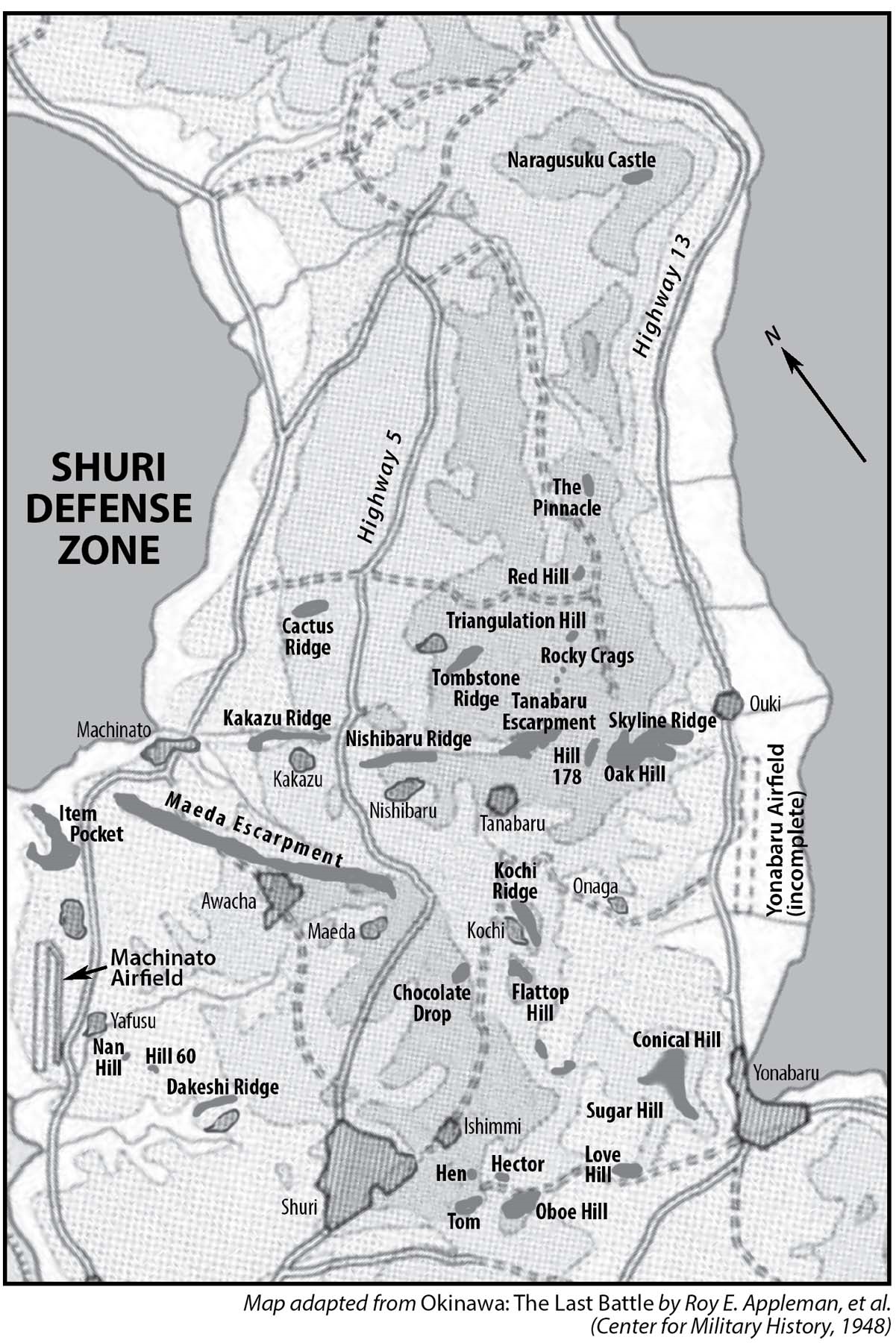

Planning began immediately for a mass nighttime infiltration of the US lines all along the Kakazu-Nishibaru-Yonabaru front. The ebullient General Chō, the Thirty-Second Army chief of staff, was delighted by the opportunity to at last take the initiative. Some staff officers strongly objected—most prominently, Colonel Yahara, the Army’s operations officer. They advocated sticking to the Thirty-Second Army’s original attritional strategy.

The counteroffensive’s primary objectives after breaking through the American lines would be Yontan and Kadena Airfields. Admiral Matome Ugaki, commander of the 5th Air Fleet and former Combined Fleet chief of staff, wrote that it was essential to “nullify the enemy’s use of those airstrips.”

The attack was initially set for the night of April 6, but was moved back to April 8, and then postponed a second time because the Japanese feared an Allied landing on Okinawa’s southern beaches that night. The counteroffensive was rescheduled for the night of April 12.

The 272nd Independent Infantry Battalion of the 62nd Division would lead the attack on the 96th Division in the Kakazu area, and the 22nd Infantry Regiment of the 24th Division would attempt to break through the American 7th Division in the east. Carrying 110-pound packs and bags of food, the 22nd marched for two days through the rain from Naha to the east coast, where it was to strike the Hourglass lines.

The infiltrators were to pass swiftly and silently through the American XXIV Corps positions in a “sinuous eel line” and conceal themselves in caves and tombs north of the battle lines. By daybreak, they were to be in camouflaged hiding places. At a predetermined time, they would strike the Allies’ rear and the two airfields. “The secrecy of our plans must be maintained to the last,” the Japanese instructions said.49

Colonel Yahara believed that the plan would squander the lives of hundreds, if not thousands, of frontline troops. After losing the argument, Yahara acted to reduce the Thirty-Second Army’s inevitable losses by quietly trimming the number of battalions committed to the operation from six to four. In so doing, he ensured that the operation would fail.

Thirty minutes before the attack began, Japanese artillery fired three thousand rounds, concentrating on the western battle line, where the 272nd Infantry Battalion hoped to breach the Deadeyes’ positions at Kakazu and Kakazu West. It was the heaviest Japanese barrage of the Pacific war.

The Americans responded with deafening volleys of gunfire from four battleships and two destroyers. Star shells interspersed with explosive rounds brightly illuminated the battlefield and exposed the attacking Japanese soldiers. The opportunity to shoot scores of enemy troops in the open elated many XXIV Corps troops, frustrated by days of being under fire from an invisible enemy.51

At Kakazu and Kakazu West, sixty enemy troops nearly broke through the 383rd Infantry’s Company G, which momentarily mistook the Japanese for Americans. Company G killed fifty-eight attackers and stopped the attempted infiltration.

Finally able to turn the tables on the Japanese streaming out of their fortifications into the open, the Deadeyes punished them with the kind of intensive mortar, artillery, and machine-gun fire that they themselves had endured for a week.

The Japanese continued to attack even when badly wounded. Some of them charged ahead with tourniquets on their legs, groins, and arms, said Private First Class Charles Moynihan, a radio operator liaison between an artillery unit and the 381st Infantry. Shot down by the score, they were soon “stacked up like a bunch of worms,” he said.

“We were pinned down by concentrated mortar fire before we could cross the hill,” wrote a Japanese soldier in the 272nd Battalion, which bore the withering fire until dawn, when it withdrew after having suffered heavy casualties. “Only four of us [in his platoon]… were left… the Akiyama Tai [1st Company, 272nd] was wiped out while infiltrating.” Another company that suffered massive casualties literally disintegrated while it was attempting to withdraw, the soldier said.

The counteroffensive at Kakazu failed in large part because of the frenzied resistance of Americans such as Tech Sergeant Beauford Anderson of the 381st Infantry—still on the Kakazu line, which the 27th Division was in the early stages of taking over.

Anderson had wound up in a cave in the saddle between Kakazu and Kakazu West with fifteen unfired Japanese mortar shells, but without a mortar to fire the shells. He solved the problem by transforming himself into a launching device: tearing the mortar shells from their casings, pulling the safety pins, rapping them against a rock to activate them, and then hurling them like footballs into a draw teeming with approaching enemy soldiers. When he ran out of Japanese mortar rounds, he threw mortar shells from his own light mortar section.

The next morning, after the echoes from the last explosions had faded, Anderson counted twenty-five bodies, seven knee mortars, and four machine guns among the debris in front of his position. Three hundred seventeen enemy dead were reported in the 96th Division area.

The Japanese counteroffensive made no inroads in the 7th Division sector on the eastern battle line. The 184th Infantry’s 2nd Battalion repulsed two attacks on their positions at Tomb Hill, north of the Tanabaru Escarpment. About thirty Japanese were killed each time. Small infiltration parties that penetrated the American lines were wiped out, one by one. Colonel Yahara believed the attacks failed in the east because the terrain was unfamiliar to the Japanese 22nd Infantry, which had marched across the island from Naha.

The counterattack met the same result the next night when, illuminated by naval star shells, the Japanese were once more repulsed. By dawn on April 14, about half of the Japanese who participated in the counteroffensive, 1,594 men, had died. Fewer than 100 Americans were killed.

While the Tenth Army briefly savored its brief respite from high casualties, terror and death continued to hurtle from the skies at the Fifth Fleet.