The last roll of the dice for the Neger crews of 363 K-Flotilla came the following night when forty-two set sail from Villers-sur-Mer. Their deployment was to be matched by other Kriegsmarine units involved in torpedo operations in the south of the Seine Bay, committed to the waters off Dungeness and also mining the sea off North Foreland. Only sixteen Negers would return, the remainder falling victim to depth charges, surface defensive fire and air attack. Matrosengefreiter Wolfgang Hoffmann was one of the fortunate few to survive.

He had patrolled the Seine estuary in search of targets until nearly full light the following day. Finding nothing, Hoffmann was about to fire his torpedo at a barge to which was tethered a barrage balloon when he sighted an Allied speedboat heading across his path at high speed. Attempting what was a doubtful shot at best, Hoffmann released his torpedo but, unsurprisingly, missed the speeding craft. He then headed for home; hugging the coastline until at about 10.00hrs he was sighted by Allied fighters and attacked. Hoffmann quickly cut the power on his Neger and the torpedo sank by the stern so that it was nearly vertical, the young pilot hoping that it would either resemble a buoy or look like it was already sinking. Not fooled by his subterfuge, the fighters continued to attack, one bullet hitting the Plexiglas cupola, splintering it and allowing some water to enter. Hoffmann restarted the motor and regained horizontal trim, firing a distress flare through the shattered canopy, after which the aircraft stopped their attack and banked away from him. It had been a lucky escape and some two hours later Hoffmann was able to stagger ashore once again on the German-held coastline.

Seven Neger pilots were captured during the mission, another mortally wounded and taken with an intact machine by the support craft LCS251 as he sat dying at the controls. The Neger was soon returned to Portsmouth for investigation. The German pilots claimed to have sunk one destroyer and one freighter as well as the probable destruction of another destroyer. In actuality a single small landing craft, LCF11, and the small 757-ton barrage balloon vessel HMS Fratton were sunk, the latter with twenty-nine of its crew. Two torpedoes also impacted against the ancient French battleship Courbet, though this had already been deliberately sunk as a Gooseberry blockship. A hit was also registered on the 5,205-ton transport ship Iddesleigh though this too had already been beached following damage sustained from a Dackel hit six nights previously. The return course of the surviving Negers revealed the dire situation of the German frontline in Normandy: they were ordered to make for Le Havre as the position at Villers was no longer tenable. Böhme and his staff would also relocate to Le Havre on 18 August, shortly afterward moving onwards to Amiens.

It was the end of the Neger’s deployment in western France. The original concept of the midget service weaponry had been to use a rotating selection of weapon types; once the Allies had learnt to counter one, a new type could be despatched. However, the Neger was clearly no secret to the Allies and obviously vulnerable due to their inability to dive. Thus their tenure in the frontline could no longer be justified and they were soon withdrawn entirely from combat, replaced by the Marder. The Linsens too were no longer novel to the enemy, consequently on 18 August both 363 and 211 K-Flotillas were also withdrawn from the coast.

The Negers of 363 K-Flotilla relocated to St Armand Tournai in Belgium and the Linsens to Strasbourg in preparation for shipment to the south of France where a fresh Allied invasion, ‘Operation Dragoon’, had begun on 15 August. The last Negers passed over the Seine on 20 August as a fresh batch of sixty Marder human torpedoes -Oblt.z.S. Peter Berger’s 364 K-Flotilla – arrived in Le Havre from Reims in Germany. They too were directed to Tournai to await possible redeployment to the south of France though naval planners were acutely aware that they faced severe transportation problems between Belgium and the French Mediterranean coast. Shortly thereafter OKM ordered the transfer of both 363 and 364 K-Flotillas to the Mediterranean. There they would pass from Böhme’s command into the localised control of Kommando Stab Italien and be made ready for action against the Allied forces of Operation Dragoon.

However, before their relocation the mauled remains of both 362 and 363 K-Flotillas returned to Suhrendorf via Amiens, Tournai and then Lübeck, to take charge of the improved Marder design, even this movement order proving to be problematic in an increasingly hostile occupied country. As well as the omnipresent threat of air attack, other forces had risen against the Wehrmacht troops, Mechanikermaat Dienemann being killed by French partisans during the road journey.

The now veteran pilots of the K-Verbände flotillas had by this time adopted a tradition of the U-boat service. Men of 362 K-Flotilla now sported silver seahorses on their caps as a flotilla emblem, the pilots of 363 wearing a small silver shark, its tail adorned with a red stripe for each successful mission. Between them they had amassed considerable awards for valour, the K-Verbände no longer labouring under the image of an untried service, but now revelling in the brief flare of propaganda attention. Once in Germany, 363 K-Flotilla’s commander L.z.S. Wetterich, who had been wounded in action off the Normandy coast, was invalided out of active service and remained at Suhrendorf to oversee future training, replaced by L.z.S. Münch as nominal flotilla chief while Wetterich retained his title as Senior Officer. The flotilla received sixty Marders, these split into six groups of ten for the purposes of training, each group commanded by a man of at least Fähnrich rank. As established in the Neger units, the flotilla would total approximately 110 men, though many of the logistical branches were only attached during combat and were shared with other human torpedo units. The flotilla composition comprised sixty pilots, sixty truck drivers to haul the Marders into position from the nearest railhead where they had been taken by railroad flat car, plus fifteen to twenty engineers and up to thirty-five headquarters staff and administrative personnel.

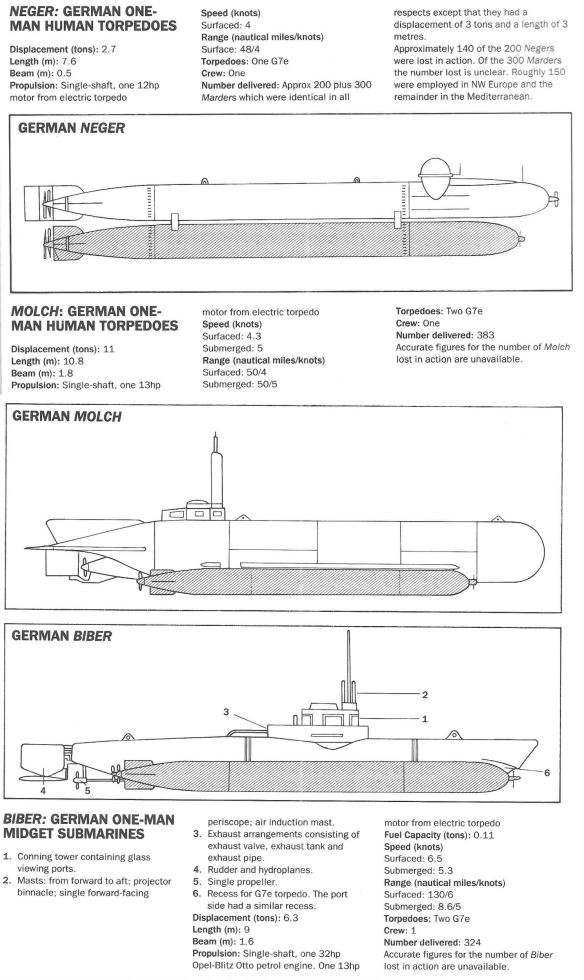

Tournai became the new concentration point for K-Verbände forces with the despatch of 261 K-Flotilla’s twenty-five Biber one-man submarines from Germany for the Belgian town on 21 August. A flotilla of Molchs was also due to arrive there from the Fatherland eight days later, but last minute appreciation of the lack of possible launch sites for this latter submarine diverted them to the south of France and Mediterranean operations.

The Biber and Molch designs were the first of what could be rightfully called midget submarines to be committed to the front line by OKW. The Biber (Beaver) was the brainchild of K.K. Hans Bartels, developed by Lübeck’s Flenderwerke and modelled closely on the British Welman craft that had been captured at Bergen on 22 November 1943. The progress on delivering a working submersible was remarkably rapid given that negotiations between the builders and Bartels began on 4 February 1944 and within six weeks they had a prototype ready for testing – the so-called ‘Bunteboot’, named after Flenderwerke Director Bunte, though known more widely as ‘Adam’. Visibly different to the eventual finished Biber design, Adam measured 7m long with a beam and draught of 96cm each. Displacing three tons of water the small boat could dive to 25m, running for two and a quarter hours at six knots. This speed almost matched her surface capability of 7 knots, though the craft’s endurance was rated at 91 nautical miles for surface travel using a petrol engine.

Following the unexpected sinking during the first attempted ‘Adam’ trial, further tests undertaken in the Trave River on 29 May proved highly successful and an immediate series of twenty-four craft were ordered, with several slight refinements that led to the final Biber model. The submarine was not without its faults though, the most prominent being the use of petrol engine power rather than diesel for surface travel. Heye expressed extreme misgivings about the use of petrol and its subsequent risk of carbon-monoxide poisoning of the operator and explosion from an accumulation of highly-combustible fumes from the engine. However, the designers and officers of Marinegruppenkommando Nord responsible for the trials expressed no such misgivings. Their rationale was that while there was an acute shortage of suitably-sized diesel engines, there were an almost unlimited supply of petrol engines that could fit the submarine’s purpose and they were almost silent into the bargain. Heye’s fears were overruled and the Biber went into immediate production at both Flenderwerke and the Italian Ansaldo-Werke, further labour on the hulls later farmed out to Ulm’s Klöckner-Humboldt-Deutz and other manufacturing companies. Thus the three sections were built in three distinct geographic locations and later assembled, almost as envisioned by Dräger years before. The specially constructed trailers used to transport the finished submarines were made by a firm in Halle and it was this asset of transportability that the K-Verbände rated highly. It was even suggested to use this portability to its most extreme by transporting a Biber by Bv222 flying boat to Egypt. There the aircraft would land either on the Great Bitter Lakes or the Suez Canal and the Biber released to find and torpedo a ship so as to block the strategically vital waterway. Fortunately for the pilot of this submarine, the far-fetched plan was abandoned as unworkable.

Costing 29,000 Reichsmarks each to produce, the final Biber model displaced 3.645 tons of water, the length having been increased to 9.035m, the beam to 1.57m with torpedoes and the draught remained the same as ‘Adam’s’. Two torpedoes of near zero specific gravity comprised the Biber’s usual armament, the torpedoes having to have neutral buoyancy lest they swamp the small parent craft with their weight and also obliterate any chance of keeping trim on discharge. This reduction of weight was achieved by the removal of half the battery from the weapon, accepting the loss of speed that this reduction would incur. Thus the TIIIb (Marder torpedoes) and TIIIc (Biber, Seehund and other midget submarine torpedoes) were capable of only 5,000m at 17.5 knots. The Biber’s two weapons were slung from an overhead rail, one on either side of the boat at the top of a scalloped cavity. They were launched with compressed air stored at 200 Bar in five steel bottles, the high-pressure air also being used for blowing ballast tanks.

As well as the torpedo, the Biber was capable of carrying mines on its twin racks. Generally the mines used were the Magnet-Akustisch-Druck (MAD) combined magnetic-acoustic-pressure triggered weapon. This was smaller than the standard midget torpedo, measuring between 5 and 5.5m in length, though having the same diameter. Set to explode by a ship of over 6,000 tons displacement passing overhead, the trigger relied on all three mechanisms to explode the warhead. The mines were heavier than torpedoes, therefore the two hemispherical ends of the weapon comprised of float chambers to offset this negative buoyancy. Correspondingly Bibers were subjected to a slight heeling to one side if a torpedo was carried on the opposite rail. When the mine was released, a spring-loaded lever held in place on either end of the mounting rail was also released, springing upward and piercing the float chambers though on discharge the mine had the disturbing habit of rising to the surface due to the slightly positive buoyancy, generally remaining there for about three minutes until enough water had flooded the holed compartments to make it sink once again. Perhaps more alarmingly the Biber also had a tendency to surface after releasing the mine, the weapon’s centre of gravity lying slightly to stern of the Biber’s, causing the boat to be in turn slightly bow heavy when loaded. Upon release, unless the operator was exceptionally skilled, the general counterbalancing action of the freed submarine would lift the bow too rapidly to be stopped.

Nevertheless, this was not necessarily a fatal design flaw. The Biber’s true Achilles Heel remained, as Heye had feared, its petrol engine and the resultant accumulation within the small craft of toxic and highly flammable fumes. A 2.5-litre, 32hp Opel-Blitz petrol truck engine provided this main propulsion, the 225 litres of petrol carried in the small craft’s tank giving a surfaced range of 100 nautical miles at 6.5 knots. Exhaust from the engine was vented outboard via a pipe that ran from the engine compartment to a small enclosure aft of the conning tower. For submerged travel the Biber was provided with three battery troughs (Type 13 T210) carrying four batteries in total (two of twenty-six cells and two of twelve cells) and a 13hp electric torpedo motor turned the 47cm diameter propeller, providing 8.6 nautical miles at 5.3 knots plus a further 8 nautical miles at 2.5 knots. The diving depth had been slightly decreased to 20m because the balance of size and weight had meant a corresponding use of 3mm sheet steel for the pressure hull. Internally, the three-sectioned hull (bolted together with rubber flanges between the joins) was strengthened by flat bar frame ribs spaced about 25cm apart. The flanges themselves were sometimes prone to leaking and Biber pilots were instructed to dive their boats for two hours to check the seals before they would be released for combat duty. One Biber veteran, Heinz Hubeler, later recounted that he had made many such dives, dropping to the seabed and reading a book until an alarm clock that he had taken for the purpose indicated that his two hours were over.

The relative weakness of this segmented hull was exacerbated by the twin-scalloped indentations that allowed streamlined stowage of the torpedoes but lessened depth charge resistance. Two heavy-duty lifting lugs were fitted to the upper hull fore and aft to enable moving by crane. Another lug was welded to the stern for towing something behind the small submarine, while yet another was fitted forward to enable the vessel to be towed to its operational area. However, experiments at using Linsens to tow the Biber resulted in failure as the small motorboats could not develop sufficient power, while S-boats were also unsuitable as they created too much wake for the Biber. Thus this task would fall to the overworked minesweepers of the R-Flotillas stationed in the combat zone. These were by no means ideal, especially those highly manoeuvrable craft fitted with the directional Voigt-Schneider propellers, but they were the best that could be provided for the K-Verbände.

The small conning tower in which the pilot’s head naturally was positioned was made of aluminium alloy casting bolted onto an oval aperture in the hull. Six rectangular ports – one aft, one forward and two others each side – provided armoured-glass windows for the operator to view his world around him. A circular hinged hatchway above was held in place by a single internal clip, another window in it providing upward view for the pilot as well. Expectations were high as the first completed Bibers began to be issued for training of their prospective crew.

However, the Biber was not an easy craft to handle. Two circular wheels, one slightly smaller in diameter than the other but both turning on the same axis immediately in front of the pilot, controlled a wooden rudder and single wooden hydroplane. It was undoubtedly a complicated and highly skilled manoeuvre to handle the hydroplane and rudder simultaneously while at the same time observing the compass, depth gauge and periscope, and perhaps even using the bilge pump as well. Correspondingly the Biber moved almost entirely surfaced, a freeboard of about 60cm showing when at normal trim, submerging only when it was absolutely necessary.

Compensating and trimming tanks had been dispensed with and solid ballast was stowed during preparation for operational use. While at sea, weight and trimming changes could only be accomplished dynamically or by partial flooding of the diving tanks situated fore and aft, both tanks free flooding with small vents in the top. This in turn made it nearly impossible to remain at periscope depth meaning that torpedo attacks also had to be conducted surfaced, though the Biber was theoretically capable of submerged firing. Pilots perfected the art of lying silently on the bottom in shallow water while awaiting an opportune moment to surface and attack whatever targets were at hand, though often when tanks were blown the Biber had an uncomfortable habit of shooting rapidly to the surface rather than making a stealthy appearance.

The periscope itself represented another problem. Due to the space constraints within the tiny aluminium conning tower the periscope was only capable of being directed forward, providing vision up to 40° to the left and to the right. The windows provided in the tower frequently became iced during the winter months rendering them useless; the pilot virtually blind other than what was visible through the periscope. Distance was difficult to estimate through the periscope, though it was fitted with cross-hairs, thus the whole operation was one of ‘point and shoot’, the torpedoes running at a little over 3m below the surface. If the forward windows were able to be used, a ring and cross hair sight was fitted near the tower that could be lined up with a bead fixed to the bow for surface firing.

Navigation was aided by a projector compass, the magnets for which were housed at the top of a sealed bronze alloy tube some 75cm in length, rigidly fixed to the forward end of the conning tower immediately in front of the periscope, passing through the tower ceiling to extend some 45cm above the craft. Behind the periscope was the boat’s air intake. Originally only 30cm above the conning tower, this was increased to a metre, all three masts joined together by metal bracing. Like the subsequent Seehund design, air was drawn in and circulated through the pilot compartment before reaching the engine, therefore acting as a source of fresh air for both the machinery and crewman. Once closed down for action the pilot was left a single oxygen bottle for breathing from, approximately thirty-six hours of air available.

Instruction for the Biber crews was undertaken at Blaukoppel near Schlutup opposite Lübeck’s Flenderwerft shipyard where the boats’ segments were primarily assembled. The camp of wooden huts was relatively isolated, three-quarters of a mile from the nearest tramline. Reckoned to require eight weeks of training, the first batch of pilots were rushed through in three, ready to follow Bartels into their first operational assignment. During their schooling the prospective pilots were often brought in to familiarise themselves with Bibers still in repair or construction in the shipyard workshops – almost a microcosm of the Baubelrung undertaken by U-boat crews. The men were next despatched to the depot ship Deneb that lay in Lübeck Bay, the Bibers in use resting either nearby in the water or housed in barges off Travemünde. Those who swiftly displayed a flair for the small submarines were tasked with instructing their flotilla mates while Bartels remained supervisor at Blaukoppel as Senior Officer, assisted by his small staff that comprised an Adjutant, Oblt.dR Mitbauer, Senior Engineering Officer, Obit. (Ing) Endler, Staff Officer, LdR Steputtat, Torpedo Officer, Lt(Ing) Preussner, and Chief Instructors, Oblt.z.S. Bollmeier, L.z.S. Bollmann, L.z.S. Kirschner, L.z.S. Dose and Oberfähnrich Breske.

The first three Bibers were delivered to Blaukoppel in May 1944, and were taken over by the eager recruits of 261 K-Flotilla. The following month saw six more completed, the number eventually rising to a production high of 117 Bibers completed in September.39 Each of the eventual ten planned Biber flotillas were supposed to consist of thirty boats and their pilots apiece, supported by an ancillary staff of nearly 200 men. As an example of the organisation of these combat units, the headquarters staff for 261 K-Flotilla as it headed for operations in France comprised:

Senior Officer: Kaptlt. (MA) Wolters (replacing Bartels who remained in Lübeck)

Engineering Officer: L.(Ing.) Schwendler

Torpedo Officer: Obit. (T) Dobat

C.P.O. (Navigation): Obersteur. Kramer

Medical Officer: Oberassistentarzst Borcher

An unnamed mine specialist officer and shore personnel numbering nearly 100 were under the command of Stabsoberfeldwebel Schmidt.

After being put onto an operational footing in August, Kaptlt. Wolters’ flotilla of Bibers faced a daunting journey from Blaukoppel to the front-line base allocated in France. As they neared the enemy the large trucks towing the canvas-draped Bibers on their trailers came under increasing pressure from air harassment as well as becoming aware of the proximity of several enemy armoured formations as the Wehrmachfs western front crumbled rapidly.

Days after the Bibers departed Germany, a fresh Linsen flotilla was also despatched, bound for Fecamp. However, the military situation on the ground had so changed by 30 August that the Linsen unit was halted in Brussels while OKM debated the wisdom of deploying them against British convoy traffic off Boulogne or Calais. As the situation worsened, they were eventually completely withdrawn and sent via Ghent to München-Gladbach in the Rhineland before possible transfer to the south of France. Their luck had deserted them though as they clashed with British armoured units at the start of their new road journey, taking heavy casualties and losing several Linsens. The mauled remains were transferred back to Lübeck for refitting before planned redeployment to the south of France. As events transpired it was to Groningen – west of the German border in The Netherlands -that the flotilla would eventually be sent on 23 October.

Wolters’ Biber unit at Tournai had in the meantime been transferred to Fecamp harbour on 29 August having also suffered losses on the way – this time to enemy aircraft. They were to be immediately launched against Allied shipping in the Seine Bay, but difficulties in getting them into the sea caused a postponement of 24 hours. By the night of 30 August, twenty-two of them had been placed in the water but due to the destruction of port facilities, damage to several Bibers and the loss of many personnel through the persistent air attacks only fourteen were able to actually sail between 21.30 and 23.30hrs. After nearly nine hours of strong winds and heavy seas twelve returned without reaching their target area, the remaining two, piloted by L.z.S. Dose and Funkmaat Bosch, claiming to have sunk a Liberty Ship and a large merchant ship between them before they too successfully returned to harbour.

In action the Biber pilots were subjected to the same trying conditions that the pilots of the human torpedoes had been. As most Biber sorties would last from one to two days – and subsequent Seehund sorties sometimes as many as ten days – German midget crewmen received a special, low-bulk or ‘klinker-free’ diet. Once under way they were instructed that during the first 24 hours they must use food tablets and thereafter energy tablets – including the DIX amphetamine cocktail – which would keep them going for another 24 hours. If they were reluctant to use DIX, which many men were once the side effects became known, many ate ‘Schoka-Kola’ a type of chocolate that comprised 52.5 per cent cocoa, 0.2 per cent caffeine and the balance sugar. To compound their discomfort many Biber pilots suffered from seasickness and owing to the inherent danger of water entering when the hatch was opened, vomited instead into the bilge. This in itself was unpleasant enough, though it was also something that had to be carefully monitored by the pilots, as one of the initial symptoms of carbon monoxide poisoning is nausea and vomiting.

After this single costly exercise the Bibers at Fecamp were withdrawn to München-Gladbach. Travelling by road they once again suffered heavy casualties along the way as Allied ground-attack aircraft controlled the skies by day. As the German convoys raced for safety, Allied pursuit caught traces of the K-Verbände units left behind on the French roads. Among them was Royal Marine Patrick Dalzel-Job, an experienced commando who had worked for Combined Operations since 1942 and ironically had taken part in training aboard the Welman midget submarine. In 1943 he had been transferred to 30 Assault Unit -a specialised group of Marines and naval officers that raced alongside more orthodox combat units at the front-line, tasked with finding men and equipment from Germany’s naval secret weapons programme, gathering all available intelligence regarding the Kriegsmarine.

On 2 September, Patrick arrived in Fecamp to learn from liberated locals that the last eight Bibers had only recently departed on their long, low trailers concealed under canvas and towed by heavy trucks. Patrick and his men managed to trace the submarines to Abbeville, and eventually discovered one on the Amiens-Bapaume road, abandoned after suffering severe damage from Allied aircraft attack:

It was almost an anti-climax after such a long search; there it was, off the side of the road where the towing lorry must have left it – a midget submarine, itself intact, on a burnt-out trailer. It was indeed much more like a miniature of a normal submarine than were the British Welmans with which I was already familiar, and it carried two twenty-one-inch torpedoes instead of the Welman’s delayed-action nose charge. Given the right circumstances and a skilful pilot, it could no doubt be a formidable weapon.

The captured Biber, its interior ravaged by fire possibly ignited by the attack or in an attempt by its crew to destroy its controls, was transported back to Portsmouth where it underwent careful inspection.

In the meantime Kommando Stab West, K.z.S. Friedrich Bohme and his staff, had also departed for the same destination as the retreating Biber unit on 1 September, marking the end of K-Verbände West’s presence in France.