The German radio listening service (B-Dienst) had detected news of Allied convoys headed to Sword Beach, protected by the so-called ‘Trout Line’ of modified landing craft on 5 July and the Neger pilots launched their weapons into the English Channel for the first time that night, twenty-six of them were wheeled along the prepared tracks and into the cold water of the English Channel under Bohme’s watchful eye. Conditions were ideal after days of squalls; the night was clear and an ebb tide took the Negers out to sea heading into Seine Bay in search of targets, while hours later the flood tide should aid their return. Though two of the torpedoes aborted their mission due to trouble with their motors the remaining Negers pressed home their attack, resulting in wildly enthusiastic success reports. Walter Gerhold – a former clerk – was among the wave of attacking Negers.

I saw the first ship shortly before two and I made it out to be a destroyer. So I estimated it at 1,200 to 1,500 metres away. As I went past I saw the second destroyer. Then I went past five destroyers on the port side. We had received a command to shoot between 4 and 5 o’clock and I was in quite a favourable position. I launched the torpedo. It jumped about two or three times out of the water. You had to measure the time with a stopwatch so that you could work out the running time. I was sweating loads and was quite nervous when the explosion came. So then I set off on my way back. I saw three destroyers following me. I cleared the windscreen and looked back at them with a pocket mirror. I thought to myself, ‘Ah … now he’s listening’ so I switched off my motor. Then he came up to my port side and stopped and I lay still also. Then they got the searchlights out and searched the sea. But we all had a towel on board so I put the towel over my head and made myself as small as possible inside. I put my trust in God and said to myself – ‘you’ll make it’.

I’ve tormented myself for years. In the small hours of the morning I’ve thought about how many people must have gone down with that ship; how many mothers had lost their sons, how many wives had lost their husbands and how many children their fathers … it really bothered me and I’ve thought about it a lot. It moves me still today. I lost my own father as well in that war.

At 03.04hrs Gerhold fired his torpedo at the tempting target. After forty seconds he registered a powerful detonation as his torpedo struck home. Dodging the ensuing storm of enemy ships racing to the scene Gerhold eventually made landfall near Honfleur where he was pulled from the water by Wehrmacht troops after scuttling his carrier torpedo. The Allies captured two other pilots when their Negers were detected and sunk. In fact it had been the British destroyer HMS Trollope that Gerhold had hit. The destroyer had been loaned from the US Navy (who had designated it DE566) on 10 January 1944 as part of the Lend-Lease Agreement. Generally attributed to an S-boat attack, Trollope was damaged so severely that she was written off as a total loss, towed away and later broken up in Scotland.

Potthast himself, leading the attack, suffered catastrophic failure in his underslung torpedo when it developed a leak that added so much weight to the weapon that it threatened to pull his carrier torpedo underwater. Jettisoning the useless torpedo his carrier was also damaged and began to leak, forcing him to abandon his Neger. Eventually he pulled himself ashore west of the Orne estuary and was taken back to the flotilla’s base by local German troops.

Observers deployed by Böhme along the coastline reported a number of large explosions to sea and much gunfire and by next morning ten Negers had been lost. However, between the remaining pilots they claimed to have sunk an Aurora class cruiser (Gerhold’s target HMS Trollope), two destroyers, one merchant ship of approximately 7,000 tons and two LSTs (one of them claimed by Matrosengefreiter Horst Berger who had also claimed a patrol boat sunk off Anzio) totalling 2,000 tons. They also claimed damage inflicted on another cruiser, destroyer, two LSTs and a pair of steamers. The results appeared to have more than justified the human torpedoes’ deployment.

However, the reality was slightly less overwhelming. Three ships had indeed been destroyed, HMS Trollope and the British minesweepers HMS Cato and Magic. Of the two minesweepers HMS Magic was the first to be hit as she lay 10 miles from Ouistreham. Many of the crew were sleeping when at 03.55hrs (British time) the torpedo exploded against the hull and the minesweeper rapidly sank with twenty-five men still aboard. A little less than an hour later HMS Cato suffered the same fate, also sinking rapidly and taking one officer and twenty-five seamen to the seabed with her. Mercifully for the Allied shipping clustered off the British beachhead, they were the only confirmed successes for the K-Verbände pilots.

Nonetheless the Wehrmacht’s propaganda machine went into overdrive at the image of an ex-clerk destroying what was believed by the Seekriegsleitung (SKL; Naval War Staff) to have been a cruiser using such a rudimentary weapon. Dönitz concurred and Gerhold became the first K-Verbände man to be awarded the Knight’s Cross on 6 July. Two days later his flotilla commander was similarly rewarded, his Knight’s Cross bestowed for his role as chief of the 361 K-Flotilla.

A second attack was rapidly planned for the following night when twenty-one Negers were launched against enemy shipping in the same area. From this desperate raid no German human torpedoes returned, several reportedly attacked by Allied aircraft, prompting Hitler to enquire of the Luftwaffe on 9 July whether they could aid returning Neger pilots by laying smokescreens. However, Potthast lived to later recount his tale in Cajus Bekker’s book K-Men:

I was one of the last to be launched and I remember the ‘ground crew’ coming up and tapping on the dome of my Neger to wish me good luck. The launching went perfectly; soon I was heading for the enemy ships. At about 3am I sighted the first line of patrol vessels, which passed me not more than three hundred yards away, but I had no intention of wasting my torpedo on them. Half an hour later I heard the first depth-charge explosions and some gunfire. Perhaps a fellow Neger had been spotted in the moonlight, for the British were on the alert. The depth charges were too distant to affect me, but I stopped my motor for fifteen minutes to await developments. A convoy of merchant ships was passing to port of me, too distant for an attack; anyhow I was determined to bag a warship.

I went on and towards 4am sighted a ‘Hunt’ class destroyer, but she turned away when no more than five hundred yards distant. The sea was freshening slightly; I was thankful that the five hours already spent in the Neger had not exhausted me. Soon I sighted several warships crossing my course. They appeared to be in quarter line formation, and I steered to attack the rear ship, which seemed larger than the others and had evidently slowed down to permit redeployment of her escorts. Was rapidly closing in on this ship; when the range was a bare three hundred yards I pulled the firing lever, then turned the Neger hard around. It seemed ages before an explosion rent the air, and in that moment my Neger was almost hurled out of the water. A sheet of flame shot upwards from the stricken ship. Almost at once I was enveloped in thick smoke and I lost all sense of direction.

Interceptions of garbled enemy radio traffic led the Germans to claim a single unidentified cruiser sunk. In actuality Potthast had hit and fatally damaged the Polish cruiser ORP Dragon, while at least two other Negers had sunk minesweeper HMS Pylades.

Following the enormous blast that devastated the Polish cruiser an elated Potthast was unable to navigate his small machine with any certainty. There were no stars to guide him and his inexact compass was of little use in the darkness of the Neger cockpit. After nearly an hour he noticed the sun dawning behind him so he reversed his course, realising that he had been sailing further away from his home port. He successfully eluded several enemy warships, though fatigue was taking its toll.

I must have been dozing when a sharp metallic blow brought me to my senses. Turning my head I saw a corvette [sic] not a hundred yards off. Instinctively I tried to duck as the bullets rained on the Neger, shattering the dome and bringing the motor to a stop. Blood was pouring down my arm and I collapsed.

Acting more on instinct than anything else Potthast managed to free himself from his stricken Neger, which plunged to the bottom. Floating barely conscious in the water Potthast was caught by a British boathook from the deck of his attacker, the minesweeper HMS Orestes, and he was hauled from the water and his injuries treated. He soon learnt that another single Neger pilot, a severely-wounded Obergefreiter, had been rescued by the enemy – though he did not realise that they two were the only survivors of the second Normandy attack by the K-Verbände.

Potthast’s target, the ‘D’ class cruiser Dragon, had seen meritorious service since commissioning in August 1918. Briefly seeing action in the First World War as part of the 5th Light Cruiser Squadron, Dragon served during the inter-war period in American, Chinese, Mediterranean and Caribbean waters before reducing to reserve on 16 July 1937. In September 1939 the ship was with Home Fleet’s 7th Cruiser Squadron, transferred first to the Mediterranean and then to South Atlantic Command, where she captured the Vichy French merchantman Touareg off the Congo in August 1940. During the Dakar operation of September 1940 she had been unsuccessfully attacked by the Vichy French submarine Persee and was stationed at Singapore on escort duties, serving with the China Force from the beginning of 1942 until February of that year and the fall of the British bastion. After carrying out strikes from Batavia at the end of February, Dragon sailed for Colombo on 28 February and joined the Eastern Fleet, where she was attached to the Slow Division. After her return to the Home Fleet in Britain she joined the 10th Cruiser Squadron until paid off in December 1942. It was then, while sitting in the Cammell-Laird dockyard that Dragon was transferred to the Polish Navy who took control of the ship on 15 January 1943. Despite her new Polish masters the ship’s name remained unchanged. Their wish to rename her Lwow was politically embarrassing to the British whose Russian ally occupied the Polish city, thus she continued to sail as ORP Dragon. Brief service in Russian convoy duties was followed by attachment to 2nd Cruiser Squadron for part of the D-Day support off Sword Beach (Force B) in June 1944. Dragon shelled batteries at Calleville-sur-Orne, Trouville, Houlgate and Caen as well as German armoured formations during the invasion until the early hours of 8 June when Potthast’s torpedo struck amidships, abreast of Q magazine. The impact caused a sympathetic detonation of the stored ammunition. Though many casualties were suffered during the explosions and resulting fires, the ship remained afloat. She was soon declared a constructive total loss, however, and was subsequently towed to and beached at the Gooseberry harbour as part of the breakwater that sheltered the fragile beachhead.

While it can be ascertained with certainty that Potthast had been responsible for the sinking of the cruiser, the second successful torpedoing that night has only recently been confirmed as sunk by human torpedo, HMS Pylades had been in almost constant service off the Normandy coast since the initial landings on 6 June 1944. The battle against German minelaying continued as German sea and air units periodically replenished already thick fields. Two explosions relatively close together shook Pylades in the early hours of 8 July, the minesweeper sinking in minutes. Her commander listed the cause of the explosions as having struck a pair of German mines, but debate has long continued as to whether they were in fact caused by the Neger attack. During 2004 a BBC film crew filmed French diver Yves Marchaland and an English television presenter as they dived the wreck of the Pylades which now lies almost upside-down in 34m of water. Conditions were less than favourable and eventually an ROV took over the task of filming the wreck in order to deduce the cause of her demise. Though the stern section of Pylades had been mangled by the force of the blasts, Ministry of Defence damage assessment expert David Manley was able to compare the difference in damage patterns caused by mines and torpedo strikes. Influence mines such as the type deployed by the Wehrmacht off Normandy leave a characteristic crimping pattern on the hull of target ships after exploding beneath them. The explosion of a torpedo did not give this signature and the Pylades bore no such distortion on her ruptured and corroding hull. Indeed she had been the victim of two torpedo strikes, the first struck the ship and incapacitated her, the second hitting and blowing a large hole in the hull, sending the minesweeper under and leaving dozens of shocked British sailors floundering in the Normandy swell. Both Neger pilots remain anonymous to this day, lost in the course of events.

For Böhme it had seemed a costly exercise. Though he was aware that a cruiser may have been sunk, not a single Neger returned. Five pilots had been captured by the British, the remainder destroyed by surface gunnery and aircraft of the RAF and Free French. A single undamaged Neger had also washed ashore to be recovered by the enemy. Nonetheless the Neger pilots’ exploits, in particular that of Walter Gerhold, perhaps served to encourage men to enter the ranks of the K-Verbände, though not necessarily into the human torpedoes. Werner Schulz, a Seehund engineer, recalled a conversation amongst new K-Verbände personnel in 1944 that showed that propaganda could not disguise the perilous nature of the human torpedoes despite the lure of glory:

‘I have heard’ an Obermaschinist told us – he introduced himself later as Kurt Keil from Uelzen – ‘that in the English Channel one-man torpedoes have grounded a Polish steamer and sunk an English destroyer. One pilot, an Oberfähnrich, has even won the Knight’s Cross. It was announced in a Wehrmacht report.’

‘That makes sense’ confirmed Oberfunkmaat Papke. ‘I heard it on the wireless.’

‘The one-man torpedoes are nevertheless pure suicide squads. They are not even proper sailors. There every Tom, Dick and Harry arrives, sits down inside the Eel [torpedo], presses on a button and bang, either they hit or they don’t.’

Nonetheless a further assault was planned for the night of 20 July pending reinforcement for the flotilla from Germany. This time the sole success was the destruction of the destroyer HMS Isis seven miles north of Arromanches, often incorrectly attributed to German mines. The 1,370-ton ship was hit amidships on the starboard side, this explosion swiftly followed by two more on the port side, blowing such a large hole that she heeled violently to port and sank in minutes. Though now treated as little more than a footnote in history, the loss of Isis left only twenty survivors. A glimpse of their experience in the cold Channel waters can be gleaned from the following account written by one of the twenty, Ken Davies:

I came aboard Isis some nine or ten days before she was mined [sic] and not only witnessed the bombarding of German shore positions but also took part in the excitement of depth-charging a suspected U-boat. I remember nothing of either event. It appears that the sights and sounds of the mine explosion and its aftermath induced some sort of mental block. I nevertheless stand by my recollections of the mining [sic] itself and of my time on the Carley Float and subsequent rescue by the American Coast Guard cutter.

I was on deck when the ship hit the mine. Shortly after this explosion there was a second, which I assumed was that of the boiler. On both occasions I was thrown to the deck. On seeing the for’ard hatch falling away, I began to release one of the Carley Floats. There must have been a dozen or more men just standing by the port rail obviously in shock and doing nothing to help themselves. They only came to life when the float hit the water. Naturally they were the first on.

The emotional strain of our situation was soon demonstrated. On my raft one young fellow’s mind went – he kept talking to his mother whilst refusing to give up the paddle he was clutching. Another was wearing a Duffel coat and a polo-necked jumper. He was asked to give up his coat to cover a fellow who was wearing only a singlet and appeared to be badly scalded or burnt. Duffel coat refused. Someone suggested taking the coat off him but wiser heads said that a struggle would have us all in the water and if that happened some would not make it back to the float.

I remember the speed with which men died. The fellow next to me said he was feeling warm at last. This I knew was a sign of hypothermia. I tried to keep him awake by talking to him, but failed. It seemed no time at all before he was as stiff as a board and we tipped him over the side.

Just as the sun was about to disappear, we saw the silhouettes of two ships. They wouldn’t have been much more than a mile away. Duffel coat stood up to shout and wave. Whether he stumbled or was given a nudge, I don’t know, but he ended up in the water. I don’t know if he got back on board or not, but then I didn’t look for him; it was at this time that a man I was told was the ship’s R.P.C. and I were fixing life-belt lights onto a paddle.

Eventually the American Coast Guard cutter spotted us and nosed between our float and another, not realising that the two were roped together. This had the effect of turning our float onto its starboard side. We had to quickly jump across to the cutter. I was second to jump and was terrified I would mistime my jump and end up in the water. In the event all went well and I was taken below and put in a bunk with white sheets!

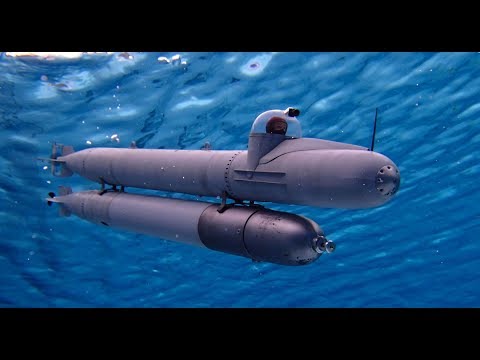

In Germany the shortcomings of the Neger human torpedo were becoming immediately obvious. Thus an improved and slightly larger model was designed and manufactured as a replacement. This new model – named the Marder – incorporated a pressure chamber immediately behind the pilot’s seat, carrying 200kgs of compressed air and a 30-litre flooding tank in the nose that added 65cm to the length of the weapon, which now measured 8.3m. The increased size raised the displacement of the Marder to 3m3 as opposed to the 2.7m3 of the Neger. With lOkgs of compressed air used in theory for every surfacing, the Marder could thus submerge up to twenty times before exhausting the air supply. A further oxygen supply was also fitted to the Marder, 200kgs of oxygen mixture connected to the pilot via a rubber tube. Released by a valve, it passed over a purifying agent while impure air was ejected by means of a small jet. Like the Neger pilots’ main breathing equipment, the fighter pilot’s mask and air bottles were also still carried for backup use.

Other refinements included the ability to secure the hinged Plexiglas dome from inside the Marder, an iron traversable ring fixed inside the manhole, which could be turned in a spiral motion by use of a special key. Once turned the ring pressed firmly against another ring fastened to the bottom of the cupola, squashing a rubber joint between them and ensuring water-tightness. This was considered vastly preferable to the Neger’s design in which the dome was removed completely, and which could only be done from the outside. A small depth gauge marked off to 30m was provided, as well as a spirit level on the left hand side of the cockpit graduated from +15° to – 15° to provide guidance for the pilot in the featureless surroundings of green seawater. In practice the pilots were trained to dive and surface at an angle around 7 to 8°. Gauges indicating the pressure inside the pressure chamber, oxygen container and cockpit were also included in the tiny cockpit. Interestingly, many Marders incorporated Italian parts, at least the stern motor compartment being manufactured in Italy and supplied complete with Italian engraved markings for the adjustment screws. Of course, these adjustments were redundant as the pilot exercised complete control over the navigation and attitude of the weapon.