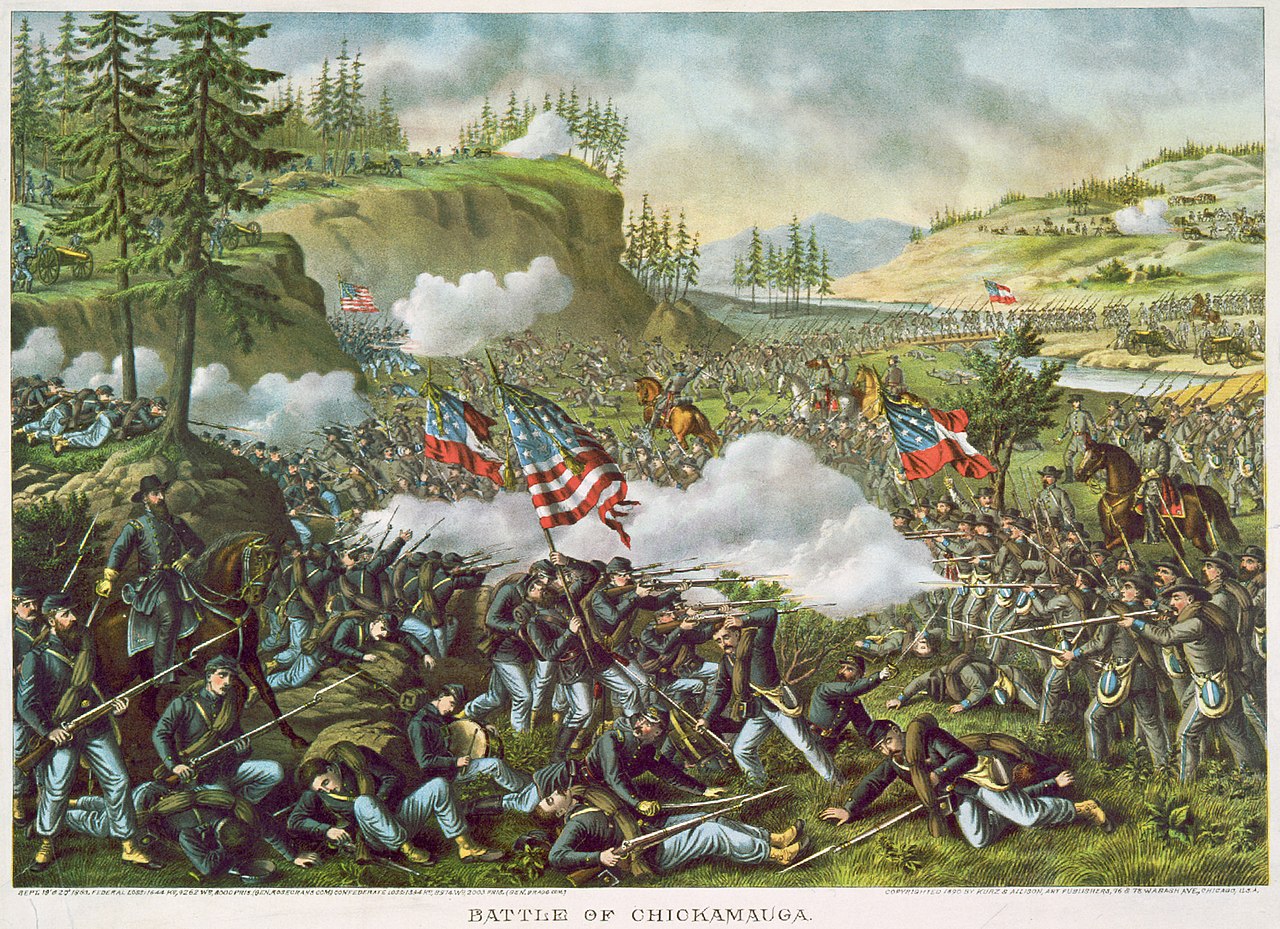

Battle of Chickamauga – Defense of Horseshoe Ridge and Union retreat, brigade details.

The Battle of Chickamauga was the second deadliest battle of the Civil War with nearly 35,000 total casualties. The Army of the Cumberland had lost over 16,000, including nearly 5,000 being captured as a result of the panic of the 20th. Bragg’s army lost even more, with 2,300 killed and over 14,500 wounded, losing nearly 18,500 all told. The casualties amounted to nearly 40% of both armies, a staggering number.

Like Longstreet, D.H. Hill was shocked that Bragg had no plans to pursue Rosecrans on the 21st:

“Whatever blunders each of us in authority committed before the battles of the 19th and 20th, and during their progress, the great blunder of all was that of not pursuing the enemy on the 21st. The day was spent in burying the dead and gathering up captured stores. Forrest, with his usual promptness, was early in the saddle, and saw that the retreat was a rout. Disorganized masses of men were hurrying to the rear; batteries of artillery were inextricably mixed with trains of wagons; disorder and confusion pervaded the broken ranks struggling to get on. Forrest sent back word to Bragg that ‘every hour was worth a thousand men.’ But the commander-in-chief did not know of the victory until the morning of the 21st, and then he did not order a pursuit. Rosecrans spent the day and the night of the 21st in hurrying his trains out of town. A breathing-space was allowed him; the panic among his troops subsided, and Chattanooga – the objective point of the campaign – was held.”

The day after Chickamauga ended, Rosecrans put his men to work digging defensive entrenchments around Chattanooga and waiting for Washington to send reinforcements. On September 23, Bragg’s army arrived at the outskirts of Chattanooga and proceeded to seize control of the surrounding heights: Missionary Ridge (to the east), Lookout Mountain (to the southwest), and Raccoon Mountain (to the west). From these key vantage points, the Confederates could not only lob long-range artillery onto the Union entrenchments but also sweep the rail and river routes that supplied the Union army. Bragg planned to lay siege to the city and starve the Union forces into surrendering.

On September 29, U. S. Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton ordered Union general Ulysses S. Grant, commander of the newly-created Military Division of the Mississippi, to go to Chattanooga to bring all the territory from the Appalachian Mountains to the Mississippi River (including a portion of Arkansas) under a single command for the first time. Considering General Rosecrans’s spotty record, Grant was given the option of replacing him with General Thomas. Hearing an inaccurate report that Rosecrans was preparing to abandon Chattanooga, Grant relieved Rosecrans of command and installed Thomas as commander of the Army of the Cumberland, telegraphing Thomas saying, “Hold Chattanooga at all hazards. I will be there as soon as possible.” Without hesitation, Thomas replied, “We will hold the town till we starve.”

What followed were some of the most amazing operations of the Civil War. Grant relieved Rosecrans and personally came to Chattanooga to oversee the effort, placing General Thomas in charge of reorganizing the Army of the Cumberland. Meanwhile, Lincoln detached General Hooker and two divisions from the Army of the Potomac and sent them west to reinforce the garrison at Chattanooga. During a maneuver in which General Hooker had moved three divisions into Chattanooga Valley hoping to occupy Rossville Gap, Hooker’s first obstacle was to bypass an artillery line the Confederates had established to block the movement of Union supplies. Initially, Grant merely used Hooker’s men to establish the “Cracker Line”, a makeshift supply line that moved food and resources into Chattanooga from Hooker’s position on Lookout Mountain.

In November 1863, the situation at Chattanooga was dire enough that Grant took the offensive in an attempt to lift the siege. By now the Confederates were holding important high ground at positions like Lookout Mountain and Missionary Ridge. First Grant ordered General Sherman and four divisions of his Army of the Tennessee to attack Bragg’s right flank, but the attempt was unsuccessful. Then, in an attempt to make an all out push, Grant ordered all forces in the vicinity to make an attack on Bragg’s men.

On November 24, 1863 Maj. Gen. Hooker captured Lookout Mountain in order to divert some of Bragg’s men away from their commanding position on Missionary Ridge. But the victory is best remembered for the almost miraculous attack on Missionary Ridge by part of General Thomas’s Army of the Cumberland.

General Sheridan was part of a force sent to attack the Confederate midsection at nearby Missionary Ridge. According to several present, when Sheridan reached the base of Ridge, he stopped and toasted the Confederate gunners, shouting out, “Here’s to you!” In response, the Confederates sprayed his men with bullets, prompting Sheridan to quip, “That was ungenerous! I’ll take your guns for that!” at which time he lit out, leading a spirited charge while screaming, “Chickamauga! Chickamauga!”. The advance actually defied Grant’s orders, since Grant, initially upset, had only ordered them to take the rifle pits at the base of Missionary Ridge, figuring that a frontal assault on that position would be futile and fatal. As Sheridan stormed ahead, General Grant caught the advance from a distance and asked General Thomas why he had ordered the attack. Thomas informed Grant that he hadn’t; his army had taken it upon itself to charge up the entire ridge.

As it turned out, historians have often criticized Grant’s orders, with acclaimed historian Peter Cozzens noting, “Grant’s order to halt at the rifle pits at the base of the ridge was misunderstood by far too many of the generals charged with executing it. Some doubted the order because they thought it absurd to stop an attack at the instant when the attackers would be most vulnerable to fire from the crest and to a counterattack. Others apparently received garbled versions of the order.” Sheridan later wrote, “Seeing the enemy thus strengthening himself, it was plain that we would have to act quickly if we expected to accomplish much, and I already began to doubt the feasibility of our remaining in the first line of rifle-pits when we should have carried them. I discussed the order with Wagner, Harker, and Sherman, and they were similarly impressed, so while anxiously awaiting the signal I sent Captain Ransom of my staff to Granger, who was at Fort Wood, to ascertain if we were to carry the first line or the ridge beyond. Shortly after Ransom started the signal guns were fired, and I told my brigade commanders to go for the ridge.”

Regardless, to the amazement of Grant and the officers watching, the men making the attack scrambled up Missionary Ridge in a series of disorganized attacks that somehow managed to send the Confederates into a rout, thereby lifting the siege on Chattanooga. With that, the Army of the Cumberland had essentially conducted the most successful frontal assault of the war spontaneously. While Pickett’s Charge, still the most famous attack of the war, was one unsuccessful charge, the Army of the Cumberland made over a dozen charges up Missionary Ridge and ultimately succeeded.

When the siege of Chattanooga was lifted, the Confederate victory at Chickamauga, the biggest battle in the Western Theater, had been rendered virtually meaningless. Not surprisingly, in the wake of Chickamauga there were recriminations among the generals involved on both sides. Chickamauga ensured Thomas continued to lead the Army of the Cumberland for the rest of the war, while the tension between Bragg and his principal subordinates bordered on outright mutiny. Longstreet discussed the unbelievable sequence of events within the Army of Tennessee’s high command over the next month:

“After moving from Virginia to try to relieve our comrades of the Army of Tennessee, we thought that we had cause to complain that the fruits of our labor had been lost, but it soon became manifest that the superior officers of that army themselves felt as much aggrieved as we at the halting policy of their chief, and were calling in letters and petitions for his removal. A number of them came to have me write the President for them. As he had not called for my opinion on military affairs since the Johnston conference of 1862, I could not take that liberty, but promised to write to the Secretary of War and to General Lee, who I thought could excuse me under the strained condition of affairs. About the same time they framed and forwarded to the President a petition praying for relief. It was written by General D. H. Hill (as he informed me since the war).

While the superior officers were asking for relief, the Confederate commander was busy looking along his lines for victims. Lieutenant-General Polk was put under charges for failing to open the battle of the 20th at daylight; Major-General Hindman was relieved under charges for conduct before the battle, when his conduct of the battle with other commanders would have relieved him of any previous misconduct, according to the customs of war, and pursuit of others was getting warm.

On the Union side the Washington authorities thought vindication important, and Major-Generals McCook and Crittenden, of the Twentieth and Twenty-first Corps, were relieved and went before a Court of Inquiry; also one of the generals of division of the Fourteenth Corps.

The President came to us on the 9th of October and called the commanders of the army to meet him at General Bragg’s office. After some talk, in the presence of General Bragg, he made known the object of the call, and asked the generals, in turn, their opinion of their commanding officer, beginning with myself. It seemed rather a stretch of authority, even with a President, and I gave an evasive answer and made an effort to turn the channel of thought, but he would not be satisfied, and got back to his question. The condition of the army was briefly referred to, and the failure to make an effort to get the fruits of our success, when the opinion was given, in substance, that our commander could be of greater service elsewhere than at the head of the Army of Tennessee. Major-General Buckner was called, and gave opinion somewhat similar. So did Major-General Cheatham, who was then commanding the corps recently commanded by Lieutenant-General Polk, and General D. H. Hill, who was called last, agreed with emphasis to the views expressed by others.”

The problem for the Confederates who wanted to be done with Bragg is that he was friends with Jefferson Davis, as Longstreet was reminded when suggesting to Davis that Bragg be replaced by Joseph E. Johnston:

“In my judgment our last opportunity was lost when we failed to follow the success at Chickamauga, and capture or disperse the Union army, and it could not be just to the service or myself to call me to a position of such responsibility. The army was part of General Joseph E. Johnston’s department, and could only be used in strong organization by him in combining its operations with his other forces in Alabama and Mississippi. I said that under him I could cheerfully work in any position. The suggestion of that name only served to increase his displeasure, and his severe rebuke.

I recognized the authority of his high position, but called to his mind that neither his words nor his manner were so impressive as the dissolving scenes that foreshadowed the dreadful end. He referred to his worry and troubles with politicians and non-combatants. In that connection, I suggested that all that the people asked for was success; with that the talk of politicians would be as spiders’ webs before him.”

Despite the negative feelings so many held about Bragg, Davis would not relieve him of command until late November 1863, well after the disastrous siege of Chattanooga was finished. By then, Bragg had successfully suspended Hindman and Polk for what he considered to be their failures during the Chickamauga campaign, and D.H. Hill was also suspended in early October.

With the failure to make anything out of the victory at Chickamauga, the Confederacy’s best chance at somehow turning the tide in the West and possibly winning the war had been lost. As a result, Chickamauga became an extremely sore subject among the Confederates who had fought there, and historians still look at it as the South’s last best chance in that theater.

D.H. Hill, who had played such a controversial role in the campaign, may have put it best:

There was no more splendid fighting in ’61, when the flower of the Southern youth was in the field, than was displayed in those bloody days of September, ’63. But it seems to me that the élan of the Southern soldier was never seen after Chickamauga – that brilliant dash which had distinguished him was gone forever. He was too intelligent not to know that the cutting in two of Georgia meant death to all his hopes. He knew that Longstreet’s absence was imperiling Lee’s safety, and that what had to be done must be done quickly. The delay in striking was exasperating to him; the failure to strike after the success was crushing to all his longings for an independent South. He fought stoutly to the last, but, after Chickamauga, with the sullenness of despair and without the enthusiasm of hope.

That ‘barren victory’ sealed the fate of the Southern Confederacy.”