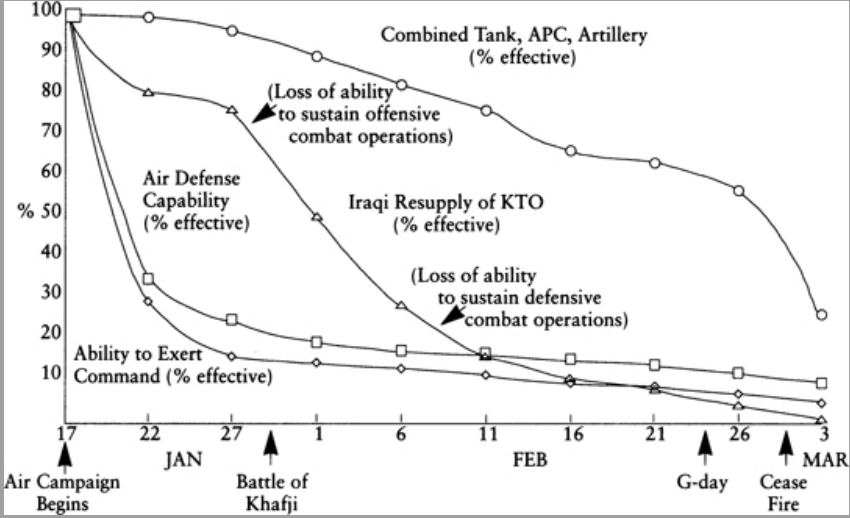

Effectiveness of Iraqi Command Structure, Air Defense, Kuwaiti Theater of Operation Resupply, and Tank-APC-Artillery “Bottom Line”: Air power shattered Hussein’s military power well in advance of G-day.

In the First Gulf War allied planners had to contend with a vast, sophisticated system of Iraqi air defenses comprised of high tech radar tracking stations coupled with anti-aircraft missiles -and all of this coordinated by a network of battle management computers in hardened facilities.

The strategic air campaign shut down the Baghdad electrical power grid by attacking twenty-seven selected generation plants and transmission facilities across the country. The power strikes, which included cruise-missile attacks and a little over 200 manned aircraft sorties, were particularly significant, for to modern military forces—and Iraq’s were very modern indeed—electrical power is a vital necessity. It cannot be stockpiled and thus, by targeting power generation, one shuts down so many other military facilities that large-scale bombing is unnecessary—one has achieved passive, as opposed to active, destruction. Again, the unprecedented accuracy of modern munitions meant that the coalition achieved maximum military effect with minimal force, minimal sorties, and minimal—in fact, no—friendly casualties. One airplane dropping two precision-guided bombs sufficed to destroy a single power-generating station’s transformer yards. During World War II, in contrast, the Eighth Air Force found it took two full combat wings, a force of 108 B-17 bombers (flying in six combat “boxes” of eighteen aircraft each), dropping a total of 648 bombs (six 1,100-pound bombs per airplane) to guarantee a 96-percent chance of getting just two hits (the minimum necessary to disable a single power-generating plant for several months) on a single power-generating plant measuring 400 by 500 feet. Thus, by the time of the Gulf war, a single strike airplane carrying two “smart” bombs could function as effectively as 108 World War II B-17 bombers carrying 648 bombs and crewed by 1,080 airmen. Further, for the number of bomber sorties in World War II required to disable just two power stations, the coalition disabled the transformer capacity of every targeted power generation facility in Iraq.47

The “psychology” which defeated this system was not one of confusion, uncertainty, or fear. It was quite the opposite: let the system work as planned, but with a few modifications.

In the opening phase of the air campaign, allied cruise missiles attacked the electrical infrastructure of Iraq, but not with explosives. Rather, the equivalent of fishing line was dispensed in bundles over the high-tension power cables running from tower to tower. But this was “special” fishing line -it was made of highly conductive material. Landing gently over the power cables, they created short circuits which tripped the breakers at the substations, and cut off electricity to the control nodes of the air defense system. Thus the “mind” -the central control- of the defenses was eliminated.

However, each individual radar site and missile battery still had local power. But all had to turn on their radar to scan for incoming enemy aircraft. And in so doing, they revealed their precise location to the electronic intelligence aircraft flown by the US, but far beyond the reach of Iraqi anti-aircraft missiles.

Now the allies knew with pinpoint accuracy the location of the radars and missiles. So, what next?

A fake air attack! Decoy missiles from American and Israeli manufacturers by the dozens were launched toward the Iraqi defenses. The missiles produced the electronic signature of planes. The Iraqi radar, working perfectly, locked on and fired salvos of missiles to engage the attackers, quickly exhausting their inventories.

And right behind the decoys came the real deal; allied jets with ordnance that followed the radar signals back to the radars and missile sites. Over 100 sites were eliminated in the space of a few hours.

And the way to downtown Baghdad and other targets was now open for conventional, non-stealthy war planes.

Coalition air leaders were initially uncertain of their success in so effectively shutting down Saddam Hussein’s air force; accordingly, they feared a possible “Air Tet” that Iraq might spring for maximum destructive and propaganda effect. Historically, there was a disturbing precedent: the New Year’s 1945 attack by the battered remnants of the Luftwaffe against Allied air bases in Western Europe, which came as a great shock and destroyed a number of Allied aircraft, demonstrating that no air force is down and out until it is planted in the ground. Thus, on January 23, day 7 of the war, the coalition began an active program of “shelter busting.” If the IQAF would not fight, it would be bombed in place. The airfield strikes were more complex than might have been imagined, and not just because of air defenses. Iraq’s many fields were large, with redundant hangar and taxiway facilities. Tallil airfield, for example, covered 9,000 acres, twice the size of London’s Heathrow Airport, and only slightly smaller than Washington’s expansive Dulles Airport. Allied strike aircraft carrying hardened laser-guided bombs began striking Iraqi shelters, which had been patterned on Warsaw Pact models designed to withstand the rigors of nuclear attack. The impact was immediate. On day 9, January 25, the IQAF appeared to “stand down,” to take stock of what was happening to it. Then, the next day, it “flushed” to Iran. Why the IQAF fled to Iran is not precisely known; was it a prearranged deal? Was it an act of defiance to Saddam—a recognition that the war was lost and an effort to try to salvage a useful force out of the disaster that had hit Iraq? The answer may never be fully known. In any case, Iraqi fighters and support aircraft fled for the border (leading to a popular joke that Iraqi fighters had a bumper sticker reading, “If you can read this, you’re on your way to Iran”). More than 120 left, trying desperately to evade the probing eye of AWACS and the F-15’s powerful air-to-air radar. Some ran out of fuel and crashed over Iranian territory. Others fell before Air Force F-15 barrier patrols (the last on February 7), raising total coalition fighter-vs.-fighter victories by the end of the war to 35, with no friendly losses. Meanwhile, back in Iraq, over 200 aircraft were destroyed on Iraqi airfields, and hardened 2,000-pound bombs devastated Iraq’s supposedly impregnable shelters and the aircraft within many of them. Eventually day and night air strikes destroyed or seriously damaged 375 shelters out of a total of 594. One night, F-117s launched a particularly effective series of attacks and were rewarded by seeing fireballs blasting out of shelter doors after they had been penetrated by hardened bombs. In sum, then, the Iraqi air force died ignominiously.

Although prewar campaign planning set generally sequential phases to the air war, giving the impression that the campaign would turn from “strategic” to “tactical” targets, and eventually (after G-day) to direct support of ground forces via close air support and battlefield air interdiction strikes, in fact the actual campaign as executed had considerable overlap; right to the end of the war, all phases of the air plan were still being flown simultaneously, though at varying levels of effort. The even greater force buildup that accompanied the second phase of the Desert Shield deployment also changed the strategic air campaign. Planners had initially anticipated that the “Phase I” strategic air campaign would sharply drop off by day 7 of the air campaign, from about 700 sorties per day to less than 100 per day. In fact, the added air assets enabled the coalition air forces to fly approximately 1,200 strategic sorties per day at the outset-almost twice as many as the planners initially had anticipated prior to war-and sorties never dropped to less than 200 per day over the first 35 days. Air defense suppression, the “Phase II” of the plan, likewise proved more extensive than in prewar plans. “Phase III” attacks against the Iraqi field army, instead of beginning about day 5 and building to about 1,200 sorties per day, started on day 1. After G-day, attacks against Iraqi forces reached nearly 1,700 sorties per day during the four-day ground operation at the end of the war.