A large number of Advanced Landing Grounds were constructed in southern England for the air build-up for the invasion of Europe; Merston, 1944.

Map showing radius of Action for fighter offensive operations January 1943 to May 1944.

Throughout 1943 and early 1944 much of the Allied air effort had been dedicated to preparing the way for the invasion of German-occupied Europe. By spring 1944 the intensity of operations was increasing as the date for D-Day, 6 June 1944, approached. The directive issued to the fighter forces stated:

The intention of the British and American fighter forces is to attain and maintain an air situation which will assure freedom of action for our forces without effective intervention by the German Air Force, and to render maximum air protection to the land and naval forces in the common object of assaulting, securing and developing the bridgehead.

A veritable air armada of P-51 Mustangs, P-47 Thunderbolts, P-38 Lightnings and various marks of Spitfire was ranged ready for battle as RAF units of Air Defence of Great Britain (ADGB) and the 2nd Tactical Air Force joined with the American VIIIth and 9th Fighter Commands. The overall plan was for the American units to provide the bulk of the escort and high-cover patrols, while the low cover, especially over the beaches, was provided by RAF Spitfires. The entire invasion area was to be given a layered screen of fighters — the first squadrons to be in position by 0425 on the morning of 6 June 1944.

The Allied fighter Order of Battle included the RAF providing 55 squadrons of Spitfires, plus a number of Mustang and Mosquito units, out of an overall fighter strength of 2,000 aircraft. It was considered that the overcrowded airfields in England would make ideal targets for German tip-and-run fighter-bombers, so each airfield was required to maintain a fighter flight on stand-by. The direct involvement of ADGB on D-Day comprised 91 Spitfires as part of the beachhead cover and a further 40 Spitfires on a sweep over airfields in Brittany and attacking any transport they found.

In June ADGB and its associated formations flew 8,474 offensive day sorties, an increase of 1,000 on the previous month. This included 25 Circus and 21 Ramrod operations, with airfields, lines of communication and power stations being the main target types. The RAF claimed the destruction of 61 aircraft during these offensive ops, for the loss of 36 pilots. It was also noted that the ‘enemy had retaliated with such vigour that fewer aircraft were destroyed than in the previous month and losses were heavier’.

In the period immediately after the D-Day landings, the ground forces were in danger of being bogged down, and in the absence of heavy weapons they had to rely on air power as ‘flying artillery’. The Spitfire squadrons carried out a good deal of this type of work, and after a while became quite proficient. The 20 mm cannon proved to be a remarkably good air-to-ground weapon against all manner of ‘soft skinned’ vehicles, although it was unable to cause any serious damage to the average German tank.

The night offensive throughout the year was still primarily aimed at supporting the operations of Bomber Command by disrupting night-fighter operations (intruder work) and engaging enemy night-fighters with RAF fighters, with Serrate playing an increased role. Although the formation of No. 100 Group in December 1943 provided a dedicated force for this work, ADGB units were still important and in February 1944 Air Marshal Harris stated that an increased effort was required to disrupt the main nigh-fighter bases such as Gilze-Rijen, Leeuwarden and Venlo. By early July he was demanding a force of 100 night-fighters and the redoubling of attacks on airfields. The reply from the Chief of the Air Staff was that the UK’s night defences could not be weakened; however, Leigh-Mallory was informed that provided he did not neglect the air defence of the UK his squadrons were to give full support to the bomber offensive.

The majority of the night offensive effort in the early part of 1944 was against airfields, with the introduction (or more accurately renaming) of the patrolling of night fighter airfields as Flower ops. From January the Mosquito VIs of No. 2 Group joined in the Flower ops and between January and May a total of 623 Flowers had been flown, 233 of these in May. However, May also brought an increase in attacks on transportation, including trains, barges, shipping and MT. Within the overall Allied strategy the invasion was of primary importance in summer 1944 and both day and night missions were tasked with this in mind, the bulk of the night sorties being Intruders. It was not until November that direct support of night bomber operations was resumed, much of the Bomber Support role becoming the responsibility of a number of specialist Mosquito squadrons with No. 100 Group of Bomber Command.

August 1944-May 1945

With the Allies ashore and established, further Command changes took place in the RAF with ADGB reverting to its Fighter Command title on 15 October 1944, still under Air Marshal Sir Roderic Hill. The Command had been given a new Directive on 22 September that recognised the changed threat to the UK, recognising that there was no significant threat West of a line from the Humber to Southampton. Fighter defences supported by full radar and Royal Observer Corps covers were to be maintained East of the line Cape Wrath-Falkirk-Leyburn-Tamworth-Brackley-Gloucester-Bournemouth, including the Shetlands and Glasgow-Clyde area. Reduced defences were to remain to the West of this line but those in Northern Ireland and in the Portree-Oban area could be withdrawn.

This led to the disbandment of No. 9 Group, which lost its operational commitments on 4 August and the rest of its duties on 18 September. It also saw No. 10 Group become semi-operational, leading to disbandment in May 1945. A number of Sector HQs were also closed. At the end of December the Command fielded 31 day and nine night squadrons. The former included 11 units with the Mustang III whilst the latter included a Tempest unit that specialised in night ops against flying bombs.

From autumn 1944 to the end of the Second World War the Command had four main roles:

- Offensive operations against rockets and flying-bombs; this primarily involved fighter-bomber attacks and armed reconnaissance against launch sites, storage sites and communications.

- Defensive operations against attacks on bomber airfields and minelaying off East coast.

- Long-range fighter to escort Bomber Command day operations.

- Night-fighter squadrons for offensive ops in support of Bomber Command night operations.

The final few months of the war saw Fighter Command strength drastically reduced from its high point in January 1943 of over 100 squadrons. In January 1945 it had 41 squadrons fielding a total establishment of 634 aircraft, which now included a large number of Mustang IIIs (234 aircraft). This arrival of Mustangs was not always well received, in December 1943 Mustangs had arrived to re-equip 65 Squadron: ‘Men stood open mouthed with disbelief. This simply couldn’t be true. Mustangs! P-51s! American junk! To exchange our beloved Spits for such rubbish! Had the bloody Air Ministry brass gone off their rockers? This was intolerable! How low could they sink? That evening the pilots gave vent to their anger in a drunken brawl, resulting in fairly expensive repairs having to be carried out to the Mess.’ (Tony Jonsson in Dancing in the Skies, Grub Street 1994)

The last throw of the dice as far as German intruder operations over England was concerned came on 3/4 March 1945 – Operation Gisella had been planned for some time and was intended as a mass attack on Bomber Command by following the bombers home and hitting them over England and at their airfields. Over 140 Ju 88s took part and the first bomber shot down was probably a 214 Squadron Fortress, which crashed at Woodbridge in Suffolk. The operation lasted less than three hours and the RAF lost at least 24 bombers, but the defences were quickly in action and eight of the attackers were shot down, with three others flying into the ground and others being written-off to various causes.

Day Fighter Operations

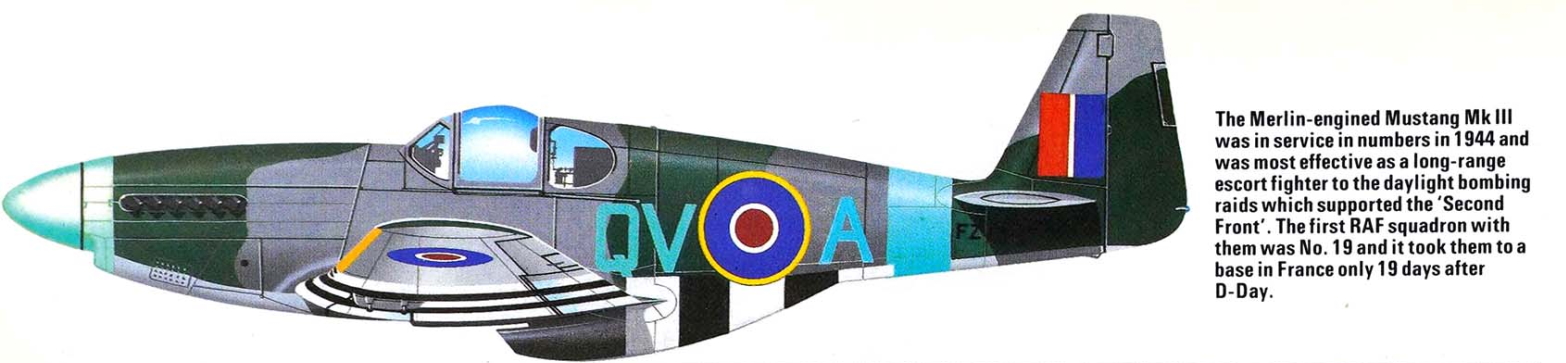

Fighter Command remained heavily involved in air operations in the latter part of 1944, initially still under the control of HQ AEAF; this included support of the airborne assault on Market-Garden in September. However, when Bomber Command was released to return to its offensive campaign, by day and night, the Command provided escort for the former and ‘bomber support’ for the latter. The first of the daylight attacks took place on 27 August when 243 bombers attacked the Rheinpreussen synthetic oil refinery at Meerbeck, near Homberg. This was the first daylight attack on Germany since August 1941 and it was escorted by nine squadrons of Spitfire IXs — all of whom, had nothing to do; the lone Bf 110 that was seen very sensibly made off in the opposite direction! Despite intense flak over the target no bombers were lost. This type of long-range escort became a routine part of the Command’s work and up to 14 Mustang and five Spitfire squadrons were eventually dedicated to this role. The Mustang was increasingly being used by Fighter Command for this role and by September there were seven squadrons of Mustang IIIs, the four original squadrons, 129, 306, 315, 316 had been joined by 19, 65 and 122 squadrons which had transferred from the 2nd TAF. Actually it had been an exchange deal in which Fighter Command also acquired four Spitfire IX squadrons, having given up five Tempest and two Spitfire XIV squadrons. The number of Mustang units continued to increase as squadrons exchanged their beloved Spitfires for the American fighter, such that by the end of April 1945 the Command included 16 Mustang squadrons.

Although the Mustangs had a better combat radius than the Spitfires they were still restricted as they had no fuselage overload tanks. ‘The radius of action of these Mustangs, after allowing 15 minutes at a fuel consumption of 60 gallons per hour for manoeuvring under combat conditions and a 10% fuel reserve, was not more 450 miles’ (AHB Summary). It was decided to fit extra tanks to the Mustangs and Spitfires despite fears that this would affect combat performance, but the ideal solution according to Fighter Command was to have usable airfields for refuelling on the Continent. These restrictions do not appear to have concerned the USAAF to the same degree and their Mustangs were regular visitors to the Berlin area. When airfields such as Ursel, Belgium, became available the Command’s Spitfires were able to provide escort 100 miles East of the Ruhr.

In February 1943 the Air Fighting Development Unit flew comparative trials between a Spitfire IX and Mustang X. The Manoeuvrability section had this to say: ‘The aircraft were compared at varying heights for their powers of manoeuvrability and it was found throughout that the Mustang, as was expected, did not have so good a turning circle as the Spitfire. By the time they were at 30,000 feet the Mustang’s controls were found to be rather mushy, while the Spitfire’s were still very crisp and even in turns during which 15 degrees of flap were used on the Mustang, the Spitfire had no difficulty in out-turning it. In rate of roll, however, it found that while the Spitfire is superior in rolling quickly from one turn to another at speeds up to 300 mph, there is very little to chose between the two at 350 mph IAS and at 400 mph the Mustang is definitely superior, its controls remaining far lighter at high speeds than those of the Spitfire. When the Spitfire was flown with wings clipped, the rate of roll improved at 400 mph so as to be almost identical with the Mustang. The manoeuvrability of the Mustang, however, is severely limited by the lack of directional stability which necessitates very heavy forces on the rudder to keep the aircraft steady.’ (AFDU Report No. 64, February 1943).

From mid October to the end of the year Fighter Command escorted 59 bomber raids, which amounted to 6,794 fighter sorties, the majority of which were recorded as arduous but boring. In the few combats that occurred claims were made for 15 enemy aircraft, for the loss of 20 RAF fighters to all causes. The escorts were largely successful and of the 124 bomber losses the vast majority were to flak. During one escort mission of 5 December the escorts reported over 100 German fighters – by far the largest number seen for a long time and an indication, although the Allies did not yet know it, of a reinforcement in preparation for the German offensive that was being planned (the Ardennes Offensive — the Battle of the Bulge).

From January 1945 to the end of the war Fighter Command flew a further 102 bomber escort missions (8,878 sorties) as well as 29 fighter sweeps over North-West Germany. The level of bomber ops increased in March with the Allied preparations for the crossing of the Rhine and the fighters were kept busy – or at least they flew long sorties but usually with little to do except watch the bombing.

The table shows Fighter Command strength had increased from 36 squadrons and 713 aircraft in 1939 to a high point of nearly 2,000 aircraft and 101 squadrons in 1943.

The statistics in the latter part of this table are misleading at first glance and suggest a massive and sudden decline after early 1943 but in reality this was primarily a re-allocation of squadrons following the formation of the Allied Expeditionary Air Force, with Fighter Command becoming ADGB and many of its units being transferred to the new tactical formations. This trend continued into early 1945 with the decreasing threat to the UK and the movement of more squadrons to the Continent.