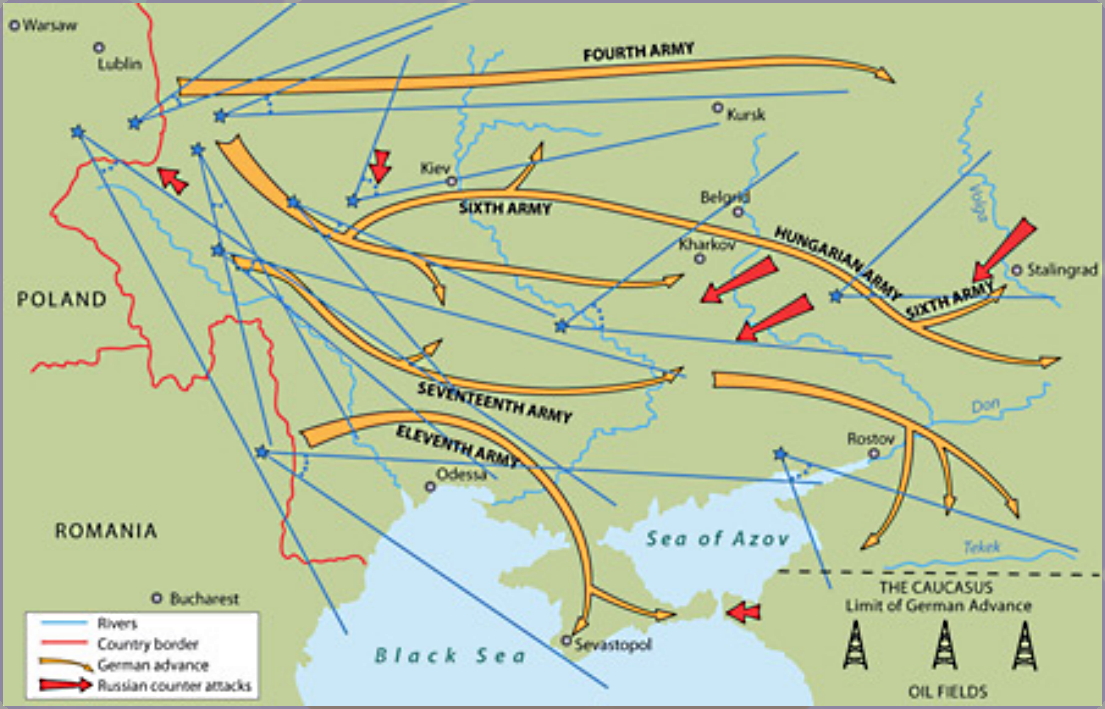

The German invasion of southern Russia in 1941. German signals and listening network was extensive due to the need to communicate over the huge distances involved. Their signals intelligence war was as complicated as the rest of this huge military campaign. Counter intelligence radio played a major part in directing the Russian partisans who later helped to destroy the German Army Group Centre in 1944.

The number of shortwave stations that sprang up in all territories occupied by Germany as she declared war on Russia in 1941 increased enormously. Wilhelm Flicke and his colleagues named the network the WNA net, which was taken from the call-sign of the Moscow station directing it. Dozens of radio transmissions on many shortwave frequency bands suddenly came to life and connected to what was to prove to be the largest espionage networks in Europe. The German listening service was overwhelmed; Lauf and other listening stations counted over 600 radiograms in the month of August following the invasion of Russia. Transmissions could be heard coming from every European country but most disturbingly some from within Germany itself. The building of a clandestine intelligence operation of this size and scope must count as being among the most successful the world has ever seen.

The most powerful network in this Russian intelligence assault on the Third Reich’s secrets was undoubtedly the Red Orchestra (Rote Kapelle), as the Abwehr named one of its Soviet espionage networks. The translation of the word kapelle into English is uncertain as it has a double meaning; it can either be a chapel of religious worship or alternatively an orchestra. The author favours the orchestra term because Flicke refers to the operators in the network as musicians in his papers and the director in Moscow as the conductor. The Soviet espionage organisation had three largely unconnected parts each of which gave the Abwehr and Gestapo many headaches. These were the Schulze-Boysen group, the Trepper group and the Red Three (Rote Drie) network, with a base in Switzerland. The first of these was brilliantly run by two men, Harro Schulze-Boysen and Arvid Harnack, who were both Communist sympathisers who managed a disparate group of over a hundred anti-Nazi agents, most of whom had been members of the Communist Party in Germany until forcibly dissolved by the Gestapo. Many in this motley crew did not involve themselves in espionage directly but observed and reported matters of interest to the network leaders. An inner circle of more active agents used their surprisingly good skills and contacts to enhance the observations of the others. Horst Heilmann worked with the Wehrmacht on decoding signals; Johann Gradenz sold aircraft spares to the Luftwaffe and knew about aircraft production; and Herbert Gollnow was a policeman and had access to counter-espionage secrets. Other shadowy figures worked in the German Foreign Office, the Ministry of Labour, and the Berlin Council, holding mainly government positions. From this mixture of observers and activists the Schulze-Boysen Group were able to accumulate a surprisingly rich vein of intelligence evaluations to report to its Moscow control.

The Abwehr’s painstaking decoding of the texts left them astonished at the high quality of the intelligence in the reports, which might concern anything from the movement of thirty army divisions being transferred from west to east, or 400,000 German soldiers holding strategic points in Italy to guarantee that her government would not make a separate peace. At another level, a technical description of a new anti-aircraft gun could be included, as well as more internal political matters. For instance, Hitler’s willingness for the Finns to make a separate peace with Russia once the Germans occupied Leningrad for the purpose of shortening her line of defence and to enable her troops to be more easily supplied was one item reported on. Details of the German war machine and its manufacturing base was another; a breakdown of the statistics of Luftwaffe strength in the air and how the 22,000 machines of first and second line aircraft were deployed. Losses of planes were also enumerated, such as the fact that ten to twelve dive bombers were being built a day but forty-five planes had been lost on the Eastern Front from 22 June to the end of September. These and many other aspects of military and economic information emerged as the horrified German cryptanalysts worked to clarify the contents.

The case caused German intelligence great concern. After breaking up the Schulze-Boysen group, the Germans found that dedicated Communist agents had been planted many years before the war without arousing any suspicion. They had used their positions in industry to gradually make excellent connections and become trusted by leaders in industry and the armed forces. The penetration and breaking down of the network in Germany by the Abwehr was a blow to Soviet intelligence, particularly as the arrests led to the discovery of networks in France and other occupied countries. The link to Moscow using the Schulze-Boysen Group’s captured radio sets was kept up, although Moscow soon realised that their network had been blown. The Russians kept up the double bluff of pretending that the network was still working, as they wanted to distract the Germans while the Soviets strengthened and built another intelligence network.

This new network was the Trepper Group, a Soviet espionage ring run by staunch Communist Leopold Trepper who posed initially as a Canadian industrialist. He started to trade in clothes and underwear in Brussels as a cover for his espionage activities and developed business interests in France, Belgium and Germany before the Second World War. He created intelligence networks of Communist agents in those places using his business activities as a front for his agents while selling black market goods to German forces occupying those countries. He supplied Hitler’s Organisation Todt (the Third Reich’s civil and military engineering group) with materials and to do this he changed his persona to that of a German businessman. He used social occasions and dinner parties to cultivate high-ranking German officials to elicit information about troop movements and building defence projects. In late December 1941 his transmitter in Brussels was detected by a directional indicator and was promptly shut down by the Abwehr and, after a long chase, he was arrested in Brussels. After interrogation, he agreed to work for the Germans by transmitting disinformation to Moscow, although he managed to include hidden signs to his controller giving warning of his plight. In September 1943 he escaped and went into hiding with the French Resistance, but by then all the members of his groups had been arrested, including the well-known French agent Suzanne Spaak who was executed at Fresnes Prison just two weeks before Paris was liberated. Trepper survived and, after the war, returned to his old business of clothes wholesaling and quite possibly continuing espionage for the Soviet Union.

Late in 1941 the intercept services at Lauf began picking up transmissions from three new operational stations, one of which transmitted from Switzerland. Their transmissions to Moscow soon established them as agent stations in the Soviet Red Orchestra. The Abwehr christened this new station Rote Drei or Red Three in the network. It took the German cryptographers until well into 1944 before they could decrypt any of the enormous volume of traffic that passed on the shortwave links to Moscow. The Abwehr rated this network as especially dangerous as it operated in Geneva in neutral Switzerland, outside the security sphere of the Third Reich, although that did not stop them investigating the operation. Its first question was easily answered as they identified Alexander Rado, a Hungarian national, as the main agent in the network. He lived at 22 Rue de Lausanne, next door to the Comintern International offices running a Communist propaganda programme around the world. Rado, whose code name was Dora, had two radio sets allocated to him and was supervised by his director from Moscow Central. Wilhelm Flicke says that one of those sets was at another address in Lausanne, 2 Chemin Longerai, where an Englishman A.A. Foote was living, but how Flicke knew any of this is not clear. He goes on to say that Foote’s cover name was ‘John’ and he did all his own cipher work and worked independently of Rado. This is strange as the Russians and particularly those in the intelligence community had a deep distrust of the British.

Rado established the Rote Drei in 1937 with a small staff in Geneva to cope with the heavy workload of transmissions. German intelligence established the names of all of them and their code names but could get no further information. In the critical period of the battles for Stalingrad and the Caucasus the radios were never quiet and, following the encirclement and capture of a German Army at Stalingrad, the Russian intelligence service faced the most important problem in its history. After the Red Army’s initial breakthrough of German lines, what was the enemy’s situation? Did they have enough reserves to strike a counter blow? Did the Red Army risk falling into a trap as they advanced so rapidly or could they pursue the enemy safely on the Southern Front? This was the finest hour for Rote Drei and indeed the Soviet intelligence service; they rose to it magnificently by answering the Red Army’s questions in detail. The often hourly reports detailing the order of battle of each of the three army groups of the Germans were received in Moscow and proved unfailingly accurate and timely. German intelligence operatives have told the author that the war was won in Switzerland, but how was Rote Drei getting its information and who were its informants? The German security agencies tried every means they could to find the leak that was haemorrhaging away the strength and dispositions of the German Army, but to no avail. They knew all the people in the Rote Drei office in Geneva and watched them closely, as they did with hundreds of people in the Führer’s Headquarters, but could not find a hint of the leak of such critical and wide-ranging information. Wilhelm Flicke wrote that, as the tide turned against Germany in the late 1940s, ‘The Rote Drei’s source of information remains the most fateful secret of World War 2’.

It was obviously a dark mystery to the Germans, but there is a simple explanation; the mysterious A.A. Foote (John), either known or unknown to Rado, was a member of the British secret service, or MI6, whose life story could fill another book. Both he and Rado were being hounded by the Abwehr, together with the Swiss counter-espionage organisation BUPO, but all the time Foote was in touch either directly or indirectly with London. The critically important information that Rado, trusted by Moscow Central, was passing on was intelligence that came from Foote. The content was so detailed and accurate over a long and critical period that it must have come from Bletchley Park. The indirect use of Rote Drei had a double advantage to the Park: first, the information came to Moscow from one of their own tried and trusted people; secondly, it safeguarded the Park’s security as Rado was seen by the Germans as a wizard at finding mysterious sources of information that they could not identify. Meanwhile, the Abwehr and Gestapo were mesmerised into strenuously seeking the answer in the Führer’s Headquarters or the inner circle of the Wehrmacht and never thought to look further afield.

Russian Battlefield Intelligence

The tactical battlefield operations of German intercept units in the field against Russian troops had an entirely different nature to those on the home front described above. Colonel Randeweg, commanding the intercept detachment in the German Army Group South in Russia, recounted his experiences that were probably similar to every intercept unit in Army Groups Centre and North on the Russian front:

The vastness of Russia’s steppes, with little in the way of good roads and almost nothing resembling a commercial or military communications system, left the Russian army with no option but to use radio to contact its formations. German signals intelligence operations therefore concentrated on long-range interception operations to determine the battle order of the Soviet army and air force west of the Ural Mountains.

The mission of Randeweg’s units was to establish the current radio techniques of Red Army operators and what German interceptors could find about their unit’s command structures and strength. The scenario gained from these operations showed a picture of the Soviet Air Force that was very different to the evaluation accepted by OKW intelligence officers as has been seen earlier. The lack of information available to Army Group South about the Red Army caused the Germans to make a grave error in underestimating the Red Army’s strength.

Russian military signals security in their frontline units was not good and tank units in particular gave themselves away by faulty security procedures before and during attacks which made German intercepts very effective. In particular, careless requests for fuel gave away their positions and condition and transmissions from tank commanders made them particularly vulnerable. In July 1942 the Russian 82nd Tank Brigade had been trapped in a large pocket by the German Ninth Army who intercepted a plain text message discussing a break-out. The Brigade Commander asked about the axes of movement for his formation and was advised on the best location for an escape. The general of the 9th ordered the escape route to be lined with his tank-killer 88mm guns which decimated the Russian T-34 tanks and prevented the break-out so the remnants of the brigade retired into swamp-land for cover. Soon messages were intercepted requesting assistance in towing their T-34s out of the muddy swamp so the German radio operators used a deception on tank commanders, pretending to be Russian and asking for their position so the towing vehicles could find them. They then used the co-ordinates to direct artillery fire on the position and, still pretending to be Russian, the operator was able to keep in touch with the tank commander until his tank was knocked out and went off the air. Finally the Russian divisional staff tried to rescue some of the brigade from its disaster by trying to reorganise the troops and ordering them by radio to assemble at designated points, which then came under further intense artillery fire. The effect of the bombardment could then be checked by transmissions from surviving Russian operators asking for help. The whole of the Russian 82nd Tank Brigade had been wiped out due to lack of radio security. Frontline Russian operators would find it difficult to equal this kind of devastating efficiency shown by German intercept companies.

In the autumn of 1943 German forces were encircled near Cherkassy in a similar way to that of the 82nd Tank Brigade and successfully broke out by intercepting Russian signals in the operation. At the behest of the German propaganda machine, the commander of the brigade of tanks told how he had been able to direct movements of his armour by use of interception of Russian transmissions. An account of it was printed in the German press and after the Russian frontline security of messages improved.

Another aspect of action in Russia was the use the Russians made of partisans. While serving as commissar with Budyonny’s cavalry, Stalin’s role as a partisan in the 1920s allowed him to observe the defects of the Russian radio services, and it taught him much about the value of disrupting the enemy’s supply lines. A band of guerrillas in the vast empty Russian steppes could attack the lightly defended supply routes of the Germans whose first intimation of an attack would be the swish of the skis of the attacker before the destruction of supplies or ammunition intended for frontline units. A major partisan offensive was launched by Stalin using such guerrilla tactics to disrupt the German Army’s ever-lengthening supply lines, causing a major headache for their listening posts. Each band carried a shortwave radio and took orders from their parent Red Army formation headquarters as to where to strike and when. Listening posts allocated to identifying these radio sets complained regularly that it was impossible for them to keep track of literally hundreds of tiny mobile stations transmitting in their sector.

As the tide of battle turned from the high water mark of Stalingrad and then Kursk, the Russian use of radio communications became more adept and the German interception service was gradually overwhelmed. As the Red Army fought along its savage 3,000-mile journey from Moscow across Russia and Poland and then through Germany, increasing numbers of German intercept companies and their equipment were destroyed or abandoned. The Russians, on the other hand, became more and more confident in their radio communication service and took less and less care as they advanced. By the time the Russians were on the outskirts of Berlin they were confident enough not to encode messages. The Germans, on the other hand, were using their skilled intercept personnel as infantry in a last ditch effort to hold back Russia’s avenging army. In the last of his papers, Wilhelm Flicke asks the great why. Why, when the intercept service revealed the growing strength of the enemy on all fields, did they not stop the war when they knew it could not be won? German soldiers continued to fight as the Russians advanced into the gardens of the Reich Chancellery and the doors of Hitler’s bunker in Berlin. The most convincing answer he received came from a German ex-soldier, wounded in battle with the loss of an arm: ‘It has to do with the German culture,’ he said, ‘we continued to fight because we were never told to stop.’