Alongside the development of the Linsen, the emergence of Kriegsmarine Kampfschwimmer (frogmen) is another aspect of the K-Verbände development intertwined with units of the Brandenburgers. This time there was additional inter-service cross-pollination with the amalgamation of men from the Waffen SS and Sicherheitdienst (SD – SS Security Police) as well as Abwehr personnel.

Frogman delivery of explosives was an idea that the German Armed Forces first used in 1915 during the First World War. The original German frogman unit that formed at this time was the 2nd Reserve Pioneer Company of Stettiner Pionierbattaillon 2. Trained in the Rhine River near Mainz they first went into action on 17 August 1915 against Russian guardships near Kowno. Successfully disabling the Russian target it was also to be the last time that the Kaiser’s frogmen were used during that conflict.

Once again the Italians provided fresh inspiration for German Kampfschwimmer, the Decima Mas having used them to great effect already in the Mediterranean. The Abwehr immediately seized on this idea and formed its own maritime sabotage troops, one of the first and the most successful of whom was Friedrich Hummel who took part in Italian raids on Gibraltar and Seville harbours. Hummel remains one of the German armed forces most colourful characters. His background had involved years in the German merchant navy aboard the sailing vessel Passat that had visited Chile, South Africa, Japan and China amongst other destinations. He had joined the Kriminalpolizei in Altona, Hamburg, eventually transferring to the dreaded SD and promoted to Hauptsturmfuhrer in 1942. Hummel had also been involved in Abwehr intelligence work in Poland on the eve of the war and in Madrid between 1942 and 1944. The Abwehr began to form small units, Marine-Einsatz-Kommandos (MEK), that would undertake tasks such as reconnaissance missions, bridge demolition, mine laying and so on. The first such MEKs to be established by the Abwehr were the MAREI and MARKO in Hamburg, which later served as templates for the Kriegsmarine when Heye’s K-Verbände took over responsibility for the maritime commando service.

The Germans possessed a genuine advantage when developing the theory of military divers. While Jacques Cousteau, a Vichy French naval officer, is credited with the creation of the aqualung, it was noted Austrian diving pioneer Hans Hass who developed the first modern rebreather, ideal for military use as it left no tell-tale bubble exhaust. The unit originated from the Dräger firm’s 1912-patented U-boat escape apparatus. The company continued to work on an evolution of this basic design until June 1942 when Dräger patented a recognisable rebreather with the air contained within a back-mounted bag. This is the device that Hans Hass used during his Aegean expedition in the summer of 1942. Hass had already excited the nautical world when he shot an underwater film ‘Pirsh unter Wasser’ (‘Stalking beneath the sea’) in the course of a 1939 diving expedition with two friends, fellow-Austrian Alfred von Wurzian and Jörg Böhler. Their journey encompassed visits to Curaçao and Bonaire, the trio being forced to return to Vienna via the United States after the outbreak of war.

In 1942 Hass planned another expedition, though its location was constrained by wartime and thus took place in the Aegean Sea. It was there that Hass tested the new ‘Dräger-Gegenlunge’ oxygen rebreather. Though limited to a depth of approximately 20m due to the risk of oxygen toxicity, it was the perfect apparatus for military purposes. Hass and Alfred von Wurzian demonstrated the pioneering equipment to the Kriegsmarine commander of the Aegean, VA Erich Förste, and his Chief Of Staff K.K. Rothe-Roth from the mole in Piraeus Harbour on 11 July 1942. Oddly, despite the success of this breathing apparatus, the Kriegsmarine were slow to grasp its potential. Von Wurzian persevered, even attempting to get officers of the Army Pioneers interested in developing his frogman ideas, but to no avail. It was not until he began talking to representatives of the Abwehr’s Ausland Abteilung II, responsible for sabotage, that he found more enthusiastic listeners though the Abwehr already possessed five specialists in ship sabotage – including Hummel.

Von Wurzian was also fortunate to meet a man who shared his vision of military frogmen within the Brandenburgers. Gefreiter Richard Reimann became his assistant, helping to develop other tools of their fledgling trade such as suitable compasses and depth gauges. In spring 1943 the two men were again asked to demonstrate the potential of the underwater fighter in Berlin, using the Olympic swimming baths before an audience of German and Italian officers. After the successful exercise Von Wurzian and Reimann found themselves invited to join the training units of the Italian Decima Mas, which they did the following May. Until September 1943 the two men worked alongside their Italian counterparts, training under the command of the outstanding athlete Tenente di vascello (Lieutenant Commander) Eugen Wolk and learning the Decima Mas’s techniques. Born of mixed German-Russian parentage in Cernogov in the Ukraine, Wolk had returned to Germany with his family during the Bolshevik revolution of 1917, where they found themselves less than welcome in a Germany teetering on the brink of wartime defeat. Moving onwards to Constantinople and then Rome, with his father’s encouragement Wolk enrolled in the naval academy at Livorno. The academy’s director, Angelo Belloni, was one of Italy’s leading experts on diving and involved in training the Decima Mas’s divers (known as ‘Gamma men’) and correspondingly nurtured Wolk’s enthusiasm for the subject of frogman operations.

Von Wurzian became a de facto member of the Abwehr while in Italy and eagerly began training. He and Reimann were in Rome when the unconditional surrender of Italy to the Allies was announced on 8 September, the German pair deciding to escape what they believed would be incarceration by the Italian authorities. Travelling on foot by night they reached German lines and discovered that Wolk and the bulk of the Decima Mas had also remained loyal to the fascist government. They would train together once more, this time in Valdagno, northeast of Verona, using the swimming pool already in existence as part of a sporting complex owned by the Manzotti textile manufacturing plant.

Wolk and Von Wurzian first arrived in the small town in the foothills of the Italian Alps on 2 January 1944, Wolk accompanied by eighty Italian frogmen and his deputy, Luigi Ferraro. Ferraro was one of a successful Italian demolition team that had sunk Allied shipping on operations from the Turkish harbours at Alexandretta (now Iskenderun) and Mersina (now Mersin). Von Wurzian in turn was accompanied by Reimann and thirty German recruits for the soon-to-be-established Lehrkommando 700. This unit provided the most complicated training structure to be seen within the K-Verbände, combining several different services within the German armed forces and intelligence apparatus. It was established at the end of March 1944 and remained based alongside the Decima Mas trainees at the swimming baths at Valdagno.

With the formation of the K-Verbände came the ‘Einsatz und Ausbildung Süd’ under Kaptlt. Heinz Schomburg that was already involved in forming Linsen units within the Mediterranean theatre. Schomburg made a brief attempt to gain complete autonomous control of the Valdagno swimming baths for the K-Verbände but encountered obstructions almost immediately from both the Abwehr and also the SS who had become interested in the development of the Kampfsch-wimmer service. Nevertheless, the thirty German recruits that were training with Von Wurzian were subsequently transferred en masse to the K-Verbände and thus became Kriegsmarine personnel. In addition to these men and the Decima Mas, there were fifteen Abwehr personnel, commanded by Hauptmann Neitzer, and ten SS men also training alongside the Kriegsmarine personnel. One of the primary reasons that Wolk encouraged such wide German interest was in order to obtain a greater recognition and source of supply for his school, which was largely ignored by the existing Italian naval hierarchy. Regardless of his motivation, the results justified his efforts and three German service branches became enmeshed alongside the Italians within the training facilities. However, with Heye’s ascendancy in controlling naval Special Forces came the crystallising of German service boundaries in Valdagno followed by the K-Verbände’s accession to overall command of the German contingent during April. Von Wurzian promptly resigned his Abwehr post immediately upon the formation of Lehrkommando 700 and became an official member of the K-Verbände.

Prior to April 1944 Wolk and Von Wurzian had trained the Germans of all three services jointly, but after the formation of the Lehrkommando, Wolk henceforth trained the Italian swimmers separately, the two nationalities being kept strictly segregated during their time spent in Valdagno. After the absorption of the school into the K-Verbände, Oblt.z.S. Sowa was placed in charge, displacing the Abwehr’s Neitzer who had acted as ‘caretaker’ director, though he remained on the premises to oversee Von Wurzian’s continuing separate training of the fifteen Abwehr men. The relationship between Sowa and Neitzer soon soured and Sowa was transferred to Heiligenhafen, his place taken by the redoubtable Hauptmann Friedrich Hummel of the Abwehr, who also promptly resigned from the intelligence service and was enlisted as a Kapitänleutnant into the K-Verbände.

The Valdagno training centre covered the initial schooling of the K-Verbände recruits, another centre soon opened in May 1944 on the island of San Giorgio in Venice Lagoon for more advanced skills, the headquarters for Lehrkommando 700 transferring to Venice also shortly afterward. As the diving arm of the K-Verbände grew the subsidiary centres were renumbered: Valdagno as Lehrkommando 704 and San Giorgio Lehrkommando 701. Space had become rather limited in Valdagno by this stage and a further training centre was opened at Bavaria’s Bad Tölz in the swimming baths at the SS Junkerschule. This new branch of the K-Verbände tree was named Lehrkommando 702.

The Venetian setting for Lehrkommando 701 was an ideal one in which the men could train. The isle of San Giorgio in Alga is situated within the Lower Lagoon in the proximity of the Isle of Trezze and Isle of San Angelo della Polvere. Benedictine monks had founded the first monastery and built a church consecrated to Saint George during the eleventh century on the small island, which lay in a strategic central position between dry land and the city of Venice. In 1717 fire destroyed the monastery and church, the island subsequently used first as a prison and then from 1806 a powder magazine for the Italian military. The 15,113m2 roughly quadrangular island was surrounded by an imposing outside wall, pierced by one small harbour on its north-western face. By the time of Lehrkommando 701’s arrival the island possessed an Italian AA unit that comprised four obsolete 7.6cm Vickers Armstrong 1914 pattern guns, one 2cm Oerlikon and three 2cm Bredas commanded by a German artilleryman, Leutnant Kummer.

There the K-Verbände men trained both on land and in the water. In the Venice Lagoon they practised attacking two old ships moored for that purpose, the freighter Tampico and the tanker Illiria. Recruits were trained in the necessary tasks that would be faced by commandos including navigation, unarmed combat and stamina – the divers being dumped at sea and ordered to swim back to their island base amidst the currents that swirled around the many small islands. In fact much information had been gleaned for the Germans by captured orders for British commandos landed at Dieppe including handbook moves straight from their adversaries’ training manuals. It was not long before Oblt.z.S. Fölsch had been placed in charge of Valdagno’s Lehrkommando 704 and Von Wurzian was promoted to Leutnant and posted as Chief Instructor to San Giorgio.

The German frogmen were not adverse to playing pranks on their Italian allies as well, stealing a rowing boat from the nearby Italian arsenal and also attempting to steal a motor torpedo boat, though they were driven away by nervous sentries firing into the darkness after them. The lightness of such moments helped to disguise the deadly nature of the lessons learnt and also continued to foster the sense of elite that the Kampfschwimmer were imbued with. However, alongside the camaraderie, hard training and horseplay, the spectre of death that followed such dangerous work as that of the frogman saboteur claimed at least two lives. On 20 June 1944 Verwaltungsmaat and professional swimmer Werner Bullin was killed in a training accident, followed on 31 August 1944 by paratrooper Obergefreiter Herbert Klamt.

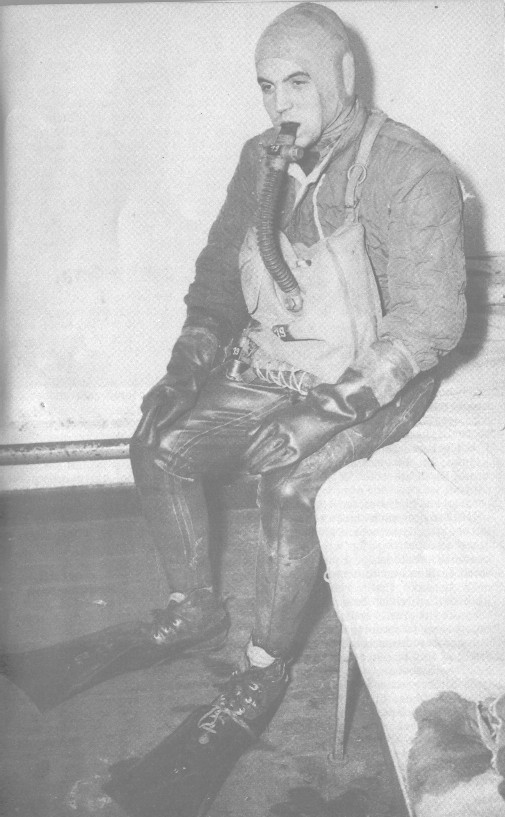

By June 1944 the divers had begun to be organised into units. The MEK MARKO that had been inherited by the K-Verbände from the Hamburg Abwehr was renamed MEK20 in April 1944 and placed initially under the command of Sonderführer KaptltdR Michael Opladen, later transferred to Obit. (MA) Bröcker as Opladen retired to the K-Verbände Staff. MEK60 under the command of Oblt.MAdR Hans-Friedrich Prinzhorn, MEK65 under Oblt.z.S.dR Karl-Ernst Richert, MEK71 under Oblt.MAdR Horst Walters and MEK80 commanded by KaptltMA Dr Waldemar Krumhaar were also ready by June. Each unit comprised one officer and twenty-two men spread between fifteen trucks that would carry their personal and operational equipment. In action German frogmen wore a rubber suit of approximately 3mm thickness that was elasticised at the wrist and ankles and had a tight-fitting neck seal. Beneath this he wore a long thick knitted woollen suit that in turn was pulled on over an extra layer of woollen undergarments. The rubber layer comprised trousers with built-in boots and a separate jacket, pulled on and the ends of both segments rolled together and sealed with a thick rubber belt. This airtight ‘dry-suit’ was then covered by a canvas outer suit that acted as camouflage, pulled tight about the body by lace adjustments. A hood – and often the application of black face paint – finished the clothing. The breathing apparatus was worn on the diver’s chest and he was trained to swim on his back toward the target, using his mouthpiece and nose clips only when necessary. Whatever natural buoyancy the trapped air within the suit and its woollen layers afforded was offset by the required lead weights, worn around the diver’s waist.

The German frogmen were armed with several varieties of sabotage weapons for use against shipping targets. Sabotage Mine I consisted of a circular rubber float with charge and firing mechanism mounted within its centre. The float was to be inflated when positioned beneath the hull of a ship, the air holding the charge in place until detonation. Sabotage Mine II was a torpedo-shaped mine, constructed in four bolted-together sections. This was attached to a ship’s keel by a simple clamp, the firing mechanism activated by water motion when the ship got underway. Sabotage Mine III was similar to the last type. Approximately 33cm long, of elliptical cross-section and with slightly convex ends, rubber buoyancy chambers could be affixed to the mine’s body which again was clamped onto a ship’s keel. As well as the motion detonator, a clockwork timing mechanism was contained within the fuse at the forward end. Allied reports indicated that often the clamps were booby-trapped so that the mine detonated if an attempt was made to unscrew it from the target vessel. Additionally, arming and firing mechanisms were fitted in both ends of the mine so that the weapon could be fired whether the vessel was proceeding forward or astern.

For attacks on bridges and caissons and such targets, the K-Verbände utilised cylindrical charges known as Muni Pakete and Nyr Pakete, containing respectively 600kg and 1,600kg of high explosive. Fitted with a timer based on the Italian ten-hour model, the weapon could only be defused by the keep ring being unscrewed. In addition, a modified GS Mine was used against bridge targets. Two buoyancy chambers were fitted at either end of the torpedo-shaped weapon enabling the mine to be floated down a river by divers and attached to the intended target. The timers used could be set for any length of time up to six days, though hourly settings were considered more accurate. In an attack against the Nijmegen bridge, the timer was set for four hours.

The first use of K-Verbände frogmen came during June 1944 when divers were assigned the task of destroying two bridges 6km northeast of Caen; the Pont de Ranville over the Orne Canal (Canal de Caen) and Pont d’Heronville that spanned the Orne River, the two waterways running parallel with each other. Situated at the eastern extremity of the Allied Normandy landing zones, the bridges had been deemed as vital targets for the invaders in order to secure the left flank of the British Sword Beach. To the east of the river and canal is the Breville highland, which overlooked the British force’s approach to the strategically important city of Caen. Therefore, Allied planners had decided that the heights must be captured, the bridges required to be left intact so that paratroopers could be supplied and reinforced once they had captured this high area. The river bridge is now famous as Pegasus Bridge, seized by an audacious British glider-borne assault in the early hours of 6 June. Though the area soon boasted bailey bridges to augment the two hard-won spans, they were considered of prime importance as targets, able to take more weight than their more makeshift counterparts.

Because of the importance of their first operation, the attacking force included Friedrich Hummel and von Wurzian – though the latter was excluded from actually entering combat and was kept in an advisory role. They and ten frogmen were despatched in three Lancia trucks from Venice to the German held area near Caen. However, on the road between Dijon and Paris one of the trucks was involved in a collision that injured four of the divers including Hummel, the wounded men being taken to a nearby field hospital and therefore unable to continue with the planned operation. Further along their path, between Paris and Caen the last two vehicles narrowly avoided the attentions of prowling RAF aircraft, hiding in thick roadside woods before the Allied fighter-bombers were able to attack.

The six remaining Kampfschwimmer and von Wurzian arrived in Caen without further incident and immediately set about organising their attack. They met with Oblt.MAdR Hans-Friedrich Prinzhorn, leader of MEK60 and Einsatzleiter for the forthcoming mission as part of Heye’s Staff from Marinegruppenkommando Süd. The divers were split into two groups of three men each. The first, comprising Feldwebel Karl-Heinz Kayser, Funkmaat Heinz Bretschneider and Obergefreiter Richard Reimann, would transport one cylindrical charge to their target bridge over the Orne Canal. The second group, of Oblt.z.S. Sowa, Oberfähnrich Albert Lindner and Fähnrich Ullrich ‘Uli’ Schulz (an ex-human torpedo pilot), would carry an identical charge against the bridge over the Orne River, the canal and river bridges some 400m apart. Both groups were briefed to pass under the newly constructed bailey bridges and carry their attack forward against the bridges that had cost so much British and German blood on the morning of D-Day itself. While the attack was carried out both Prinzhorn and von Wurzian planned to remain on the bank of the Orne River, waiting near the spot where the divers were to return.

On the afternoon of 22 June the two 1,600kg heavy torpedo charges were prepared for action on the riverbank, but a brief flurry of British artillery fire scattered the group of men working around the torpedoes, save for the torpedo mechanic responsible for their smooth operation who doggedly remained working on the explosives as shells landed nearby. Within minutes of the barrage ending he activated the fuses, set to blow at 05.30hrs. Built and tested at Kieler Werft they were designed to have enough flotation to rest approximately half a metre below the water surface where divers could easily manoeuvre them into position. However, with the decreased density of fresh over salt water, the two charges promptly sank into the thick silt of the riverbed the moment they were launched. A makeshift solution was found after Prinzhorn sent his men racing to obtain empty petrol cans, which were then tied together with rope, the heavy torpedo slung between them and resting on the extra buoyancy.

The first group led by Kayser entered the canal water as night fell. Though less than a kilometre from the front line they faced an arduous swim of 12km to their target and the same to return. Kayser and Bretschneider took the lead, each pulling one side of the torpedo against the light current that they faced on the outward journey. Reimann took the rear position, guiding the torpedo and providing directional steerage to the unwieldy device. His transpired to be a nightmarish task as the rear petrol cans lost air allowing the stern of the torpedo to sink into the canal until it dragged once again in the silt. Reimann was constantly forced to submerge and lift the weapon, in the end resting the heavy torpedo on his straining shoulder as they inched up the canal with Reimann stumbling on foot through the thick silt.

Then close ahead we sighted the first bridge, the one we were due to pass under. Visibility was poor; we heard what seemed a sentry’s footsteps on the wooden bridge. As a precaution we dived, passing under the bridge submerged. With the ropes we kept down the buoyant nose of the mine, while Reimann rested the tail on his shoulder.

Eventually, amidst the dying echoes of a German artillery bombardment of that same bridge, their target materialised before them and the fatigued men quietly attached their charge to central pilings by embedding anchors into the river bottom that was thankfully more solid sand and gravel than silt. Once their weapon was positioned about a metre off the bottom, the timer already ticking steadily, the three men gently finned in the now currentless water towards the safety of the German lines as daybreak gradually crept into the eastern sky. They stayed together for the return, Reimann particularly exhausted by the difficult outward journey. Their mission was successful as the timer activated its charge slightly before its planned time, destroying what the Germans believed to be the main Orne Canal bridge.

The second mission was also successful and no less dramatic. The group made their way downstream towards their target in the Orne River aided by the current on their outward journey, Schulz and Sowa at the torpedo’s head and Lindner pushing its tail. They had managed only a few hundred metres, still visible to their shore party when Sowa began to complain of sore feet, his fins apparently causing him great distress. Sowa immediately broke away and swam for the bank as the support personnel ran towards him. Encouraged to return to his comrades, Sowa’s nerve broke completely and he began to weep while clinging to terra firma. Despite this unforeseen setback the two remaining men still with the torpedo and its ticking clock decided to press on.

The pair managed to negotiate a wooden barrier that lay across the river and soon afterward sighted what they believed was their primary target. Affixing the weapon to the riverbed they were dismayed to find the current too strong for their return, making little headway against it and threatened by the noise made as they finned harder and harder, frequently breaking the still surface of the water. Faced with little option they allowed themselves to drift slightly with the current, past their bridge and sought shelter on the riverbank – though the pit they chose was swiftly found to have once been an Allied latrine. With dawn breaking, they had no choice but to remain where they were and at 05.30hrs a huge explosion heralded success, the pair remaining within their stinking hiding place until night fell on 23 June. Faced with the same river current they made a difficult decision – to leave the river on its far bank, cross the 400m to the canal and swim back along its placid waters. Despite the obvious peril, their triumph was absolute and the two exhausted men were warmly received when they finally made landfall in German territory. However, Sowa was not amongst the men that greeted them. Ashamed of his breakdown he had waited anxiously for news of his comrades. When they failed to return that night or the following day he took it upon himself to enter the river and search for them. With British sentries alerted by the explosions to the possible danger of saboteurs he was seen and taken prisoner after being wounded in a brief burst of gunfire.

This baptismal raid had been successful – but not completely. As the first group had returned and were debriefed by Prinzhorn on the river-bank it became apparent that the planned target area and where the torpedo had actually been placed did not match. Due to what several historians have described as an ‘incorrect sketch’ of the target area, it appears that the wrong bridge was mined. There were apparently two bridges to negotiate before arriving at the one now called ‘Pegasus Bridge’. Predictably, the same held true for the two surviving men of the second group, the nearby Pont d’Heronville still standing after the weapon’s detonation.43 Nevertheless, the K-Verbände had proved themselves equal to the task of commando raids. One man had been lost out of six and two bridges had been successfully destroyed.