The story of the Sherman tank in Soviet service during World War II has received little attention outside Russia – or as it was, the Soviet Union. Although from 1941 to 1945, the USSR and the United States were allies, the Cold War commenced almost immediately after the defeat of Germany and any help that the western Allies may have extended to the Russian war effort was regarded by Stalin as a political embarrassment – and indeed has continued to be so even until the present day, although on something of a reduced scale. In fairness to the Soviets however, the majority of the tanks supplied under the Lend-Lease agreement performed poorly against their German counterparts and the greatest assistance came in the form of the huge number of Jeeps, trucks and canned food, the latter often derisorily referred to as the Second Front by the Red Army’s soldiers.

Although many official documents and photographs have been released since the break-up of the Soviet Union, many more are still denied to foreigners and all were of course recorded in Russian. The tendency to downplay the contribution of the Lend-Lease equipment means that very few images of the Soviet Shermans have ever been released. This has been alleviated in part by the reasonably large number of captured German photographs available. Unfortunately, these usually depict vehicles that are damaged to some degree and in most cases the captions have been lost. They are on the other hand, of a very high quality and we have used those that are available in this book.

One of the difficulties most often faced by Sherman researchers is attempting to determine which variant of the tank is being discussed or depicted in a particular photograph. However, except for two examples of the M4A4 model received for evaluation purposes, all the Sherman tanks delivered to the Soviet Union were the diesel engine M4A2 version, initially armed with the 75mm and later the long-barrelled 76mm gun. This model was chosen intentionally with the aim of placing the least possible strain on the Russian supply system as all their medium and heavy tanks were diesel powered.

Shipped from the United States via Siberia in the north or Iran in the south from November 1942 until the war’s end in mid-1945, in all 4,102 M4A2 Sherman tanks were delivered. This figure comprised 2,007 75mm armed vehicles and 2,095 with the 76mm gun. Exact figures for losses en route are not known but in total 417 M3 and M4 Medium tanks were lost and it would seem likely that the majority of these were M3 Mediums as the sea routes were much safer by the time the Shermans were dispatched. Curiously, Russian contemporary sources list only 3,664 deliveries with 2,653 vehicles being supplied to front-line units. The difference in these two figures was due to the high number of western tanks retained by training units. American built vehicles in particular were more reliable in addition to being mechanically more forgiving to inexperienced tank crews. These attributes enabled the Soviets to more easily and quickly train replacements and compensate for the extremely high loss rate among tank crews.

There is no obvious explanation for the discrepancy of 438 vehicles between the US and Soviet figures. Note that the US figure of 4,102 tanks shipped includes the 417 lost at sea. The detailed break-up by year given by the Russians is 36 for 1942; 469 for 1943; 2,345 for 1944 and 814 for 1945. Of the tanks supplied to front-line units, 36 were issued in 1942; 469 in 1943, 1,578 in 1944 and 570 in 1945.

The first deliveries were the 75mm armed versions of the M4A2, including almost every possible configuration ranging from the early, so called Direct Vision (DV), model to the later dry stowage variants with the one-piece glacis and appliqué armour plates on the hull sides. The 76mm versions were first equipped with the Vertical Volute Spring Suspension (VVSS) but Horizontal Volute Spring Suspension (HVSS) variants arrived in time for the Manchurian Campaign of August 1945, if not earlier.

The M4A2 was the second model of the M4 Medium tank to enter production and the first variant with a welded upper hull. It was powered by the General Motors 6046 twin, in-line 12 cylinder liquid cooled diesel engine developed for, and already in use with, the M3A3 and M3A5 Medium tank. In all 8,053 examples of the 75mm armed version of the M4A2 were produced from April 1942 to May 1944 with 7,413 of these being allocated to the Lend-Lease programme – the vast majority going to British and Commonwealth forces. In May 1944, the Sherman program switched to the 76mm gun with 2,915 of these tanks being built until production was halted in May 1945.

The Soviets referred to the tank – regardless of its armament – by its official US Army nomenclature of M4, or in Russian, M Chetyrye – shortened to Emcha. Their crews were referred to as Emchisti.

The Emchas enjoyed a much better reputation than the earlier Lend-Lease tanks such as the American M3 Medium or the British Matilda. They were liked by their crews who were grateful for the Sherman’s relative comfort and general habitability and also appreciated by the higher echelons for their mechanical reliability. These qualities were somewhat lacking in the T-34 and contributed to the Emcha’s efficiency during a campaign. This goes some way to explaining why an elite unit such as the 9th Guards Mechanized Corps had three of its brigades equipped with Shermans and not the locally developed T-34. As another example, the 1st Guards Mechanized Corps traded its powerful T-34/85s for M4A2s in late 1944 in preparation for the final offensive into the heart of Germany. Mounted in the commander’s cupola, the .50 calibre M2 heavy machine gun was much appreciated in street fighting and for anti-aircraft defence. Although it was generally awkward for the crew to operate, the gun was easily dismounted to allow the accompanying infantry to use it. Mechanically, the twin diesel engine had plentiful torque and could be clutched separately, allowing a very quiet advance at low speed especially if the tank ran on rubber tracks which the T- 34 could not do. The overall longer life of the Emcha’s tracks was also an advantage, surviving roughly twice as long as Soviet tracks, with the rubber variants capable of giving up to 5,000 km service. This was however in favourable conditions and terrain and the Russians found that the metal tracks particularly suffered from loss of grip on snow and ice and that in extremely high temperatures – such as those encountered during the summer of 1944 while crossing Romania and in August 1945 in Manchuria – the Emcha’s suspension was prone to overheating and damage, with the rubber block tracks and roadwheel tyres disintegrating.

It was commonly believed that the diesel fuel used with the M4A2 presented a lower fire risk if the tank was hit and this was undoubtedly one reason for the type’s popularity. Tests carried out by the US Army however established that the high flammability of the Sherman was due to inadequate ammunition stowage and had no link to the type of engine fuel used. This problem was addressed by the introduction of a system referred to as Wet Stowage whereby the tank’s ammunition racks were moved from the side sponsons to the hull floor and placed inside a protective, water filled bin. If the ammunition racks were penetrated the water would, in theory, prevent a fire from igniting the ammunition. In practice, the whole system was rendered useless if rounds were left scattered about the hull floor as they often were. Only the 76mm variant of the Emcha received this modification.

Another advantage was the Emcha’s five man crew which left the commander free to control and observe. This efficient combination was not introduced in the T-34 until the production of the 85mm armed model in 1944. Added to this were the excellent American radios which allowed for efficient command and control. Despite its advantages, the Soviets complained of a number of shortcomings in the Emcha in comparison to the T-34. Most notably were the inferior ballistic qualities of its non-sloped armour, its high profile, high centre of gravity, its lack of adequate flotation – caused by the narrow tracks – and its wider turning radius. The claim however that the T-34 was better armed should be regarded sceptically. The Emcha’s 75mm main gun was roughly equal in penetrating power to the Soviet 76.2mm while its High Explosive (HE) performance was vastly superior – in fact, the US Army’s 75mm HE shell was in a class of its own. The armour piercing capacity of the US 76mm gun was at least comparable to the Soviet 85mm as was proven in the Korean War – and the HE capability equal, in spite of the larger calibre of the Russian weapon. The American optical sights were also superior to the Soviet types, although it is probable that the stabilized gun of the American tank was not often utilised or even used to its full potential as it required extensive training and maintenance. And as regards the latter, the Soviets did indeed have a legitimate complaint, with few spare parts other than complete engines being delivered, necessitating such desperate measures as the cannibalisation of battlefield wrecks in order to keep vehicles running.

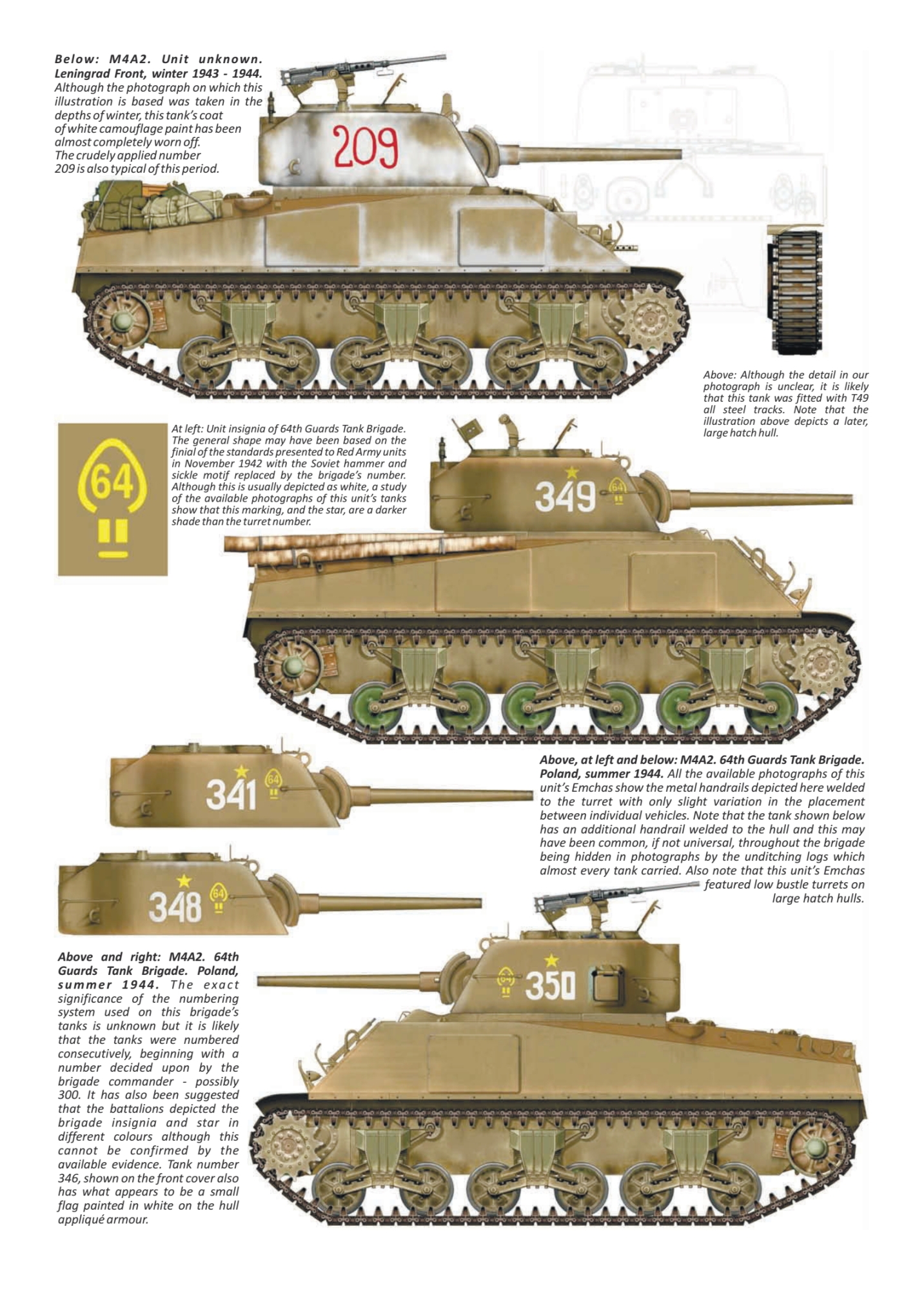

There seems to have been no attempt to alter the camouflage and markings in which the tanks were delivered including the vehicle’s US Army registration number. The single, known exception to this being the application of whitewash as a form of camouflage during the winter months. The notations in Russian that can be observed in many photographs stencilled onto the hull sides of numerous tanks were applied in the United States and were instructions regarding the vehicle’s maintenance. The tactical numbers and markings applied by the Russians are a much more complex matter being decided at corps level or lower and records are either sparse or non-existent. For the most part our knowledge of their meaning is restricted to what western researchers have been able to decipher from photographs in the years since the end of the war.

When the war in the east began in June 1941, the Soviet armoured force was made up of independent brigades, divisions and corps. Except for one or two units stationed in the Far East, the divisional organisation was quickly dropped and although some brigade sized formations continued to operate independently, the basic unit became the corps – roughly equivalent in size to a German division. Each corps was numbered and named according to its make-up and principal mission as either Cavalry, Rifles, Artillery, Airborne, Aviation, Mechanised or Tank and usually two or three corps were grouped into an army.

In 1944-1945, a typical Tank Army comprised two Tank Corps and one Mechanized Corps in addition to the various brigades and regiments of support weapons. Such a formation was capable of fielding, at full strength, approximately 600 tanks and 200 direct support self-propelled guns. The average Tank Corps comprised three Tank Brigades, with over 200 tanks and two regiments of self-propelled guns, with approximately 40 guns, and various support units. A typical Mechanized Corps could deploy three Mechanized Brigades, with three battalions of motorized infantry and a Tank Regiment, plus a Tank Brigade and various support units. Among the latter were three regiments of self-propelled artillery categorised as Light, Medium and Heavy. The Light regiment was usually equipped with SU-76 vehicles while the Medium regiment fielded the SU-85 or SU-100 and the Heavy regiment operated the powerful ISU-122 or SU-152. In total a Mechanised Corps contained over 180 tanks and more than 60 self-propelled guns.

In 1945, the Soviets managed to field 6 Tank Armies deploying 17 Tank and Mechanized Corps, plus 19 independent Tank and Mechanized Corps, in addition to approximately 50 independent Tank Brigades and more than 100 Tank and SP Artillery Regiments.

The other large users of the Emcha were the Cavalry Corps, of which the Red Army had seven in 1944, all being subsequently upgraded to Guards status by the end of the war (see note 5). Of these, 5th Cavalry Corps and 7th Cavalry Corps are known to have received Emchas in 1944. Such a corps normally fielded three Cavalry Divisions, each of which deployed a Tank Regiment of approximately 40 tanks, probably one third of them Light tanks – typically British built Valentines – while the remaining two thirds were Mediums, in this case Emchas. The pairing of these Lend-Lease tanks was quite common in 1944-1945. Lastly, some independent regiments also received the Emcha while providing general support to infantry units as Army level troops.

The Soviet method of fighting mobile battles was referred to as the doctrine of Deep Battle. The first chapter of The Provisional Field Service Regulations for the Workers’ and Peasants’ Red Army of 1936 explained the principle thus: “The resources of modern defence technology enable one to deliver simultaneous strikes on the enemy tactical layout over the entire depth of his dispositions. There are now enhanced possibilities of rapid regrouping, of sudden turning movements, and of seizing the enemy’s rear areas and thus getting astride his axis of withdrawal. In an attack, the enemy should be surrounded and completely destroyed”.

To put it simply, the highly mobile tank and mechanised formations were not directed to search out and destroy large encirclements of enemy forces – this was the objective of the following infantry – but to move at top speed, regardless of casualties, towards important objectives deep in the enemy’s rear and to hold them until the infantry caught up. Key facilities, such as railway networks, large supply depots, road junctions and bridges would be thus denied to the enemy, paralysing him and forcing his withdrawal. The type of formation best suited to this style of warfare was the Mechanized Corps, which had a better balance of tanks and infantry than the Tank Corps, and was therefore better suited to holding key objectives against the inevitable German counter-attacks. This may explain why many of the mechanically reliable Emchas were allocated to the various Mechanized Corps.

In retrospect, the Emcha constituted a large and arguably, the most successful part of the Lend-Lease Medium tank program to the USSR. It arrived too late to take part in the Stalingrad battles of late 1942 and early 1943 and had no real impact on the huge armoured engagements at Kursk in July 1943. Thus it missed the most critical – and most highly publicised – phase of the Eastern Front Campaign, when the conflict was truly still in the balance. Nevertheless, it was an important weapon system and provided a reliable, if unremarkable, tank to support the Soviet Blitzkrieg when it equipped a fair proportion of the Guards Mechanized Corps of 1944-1945.