The Start of the Attack

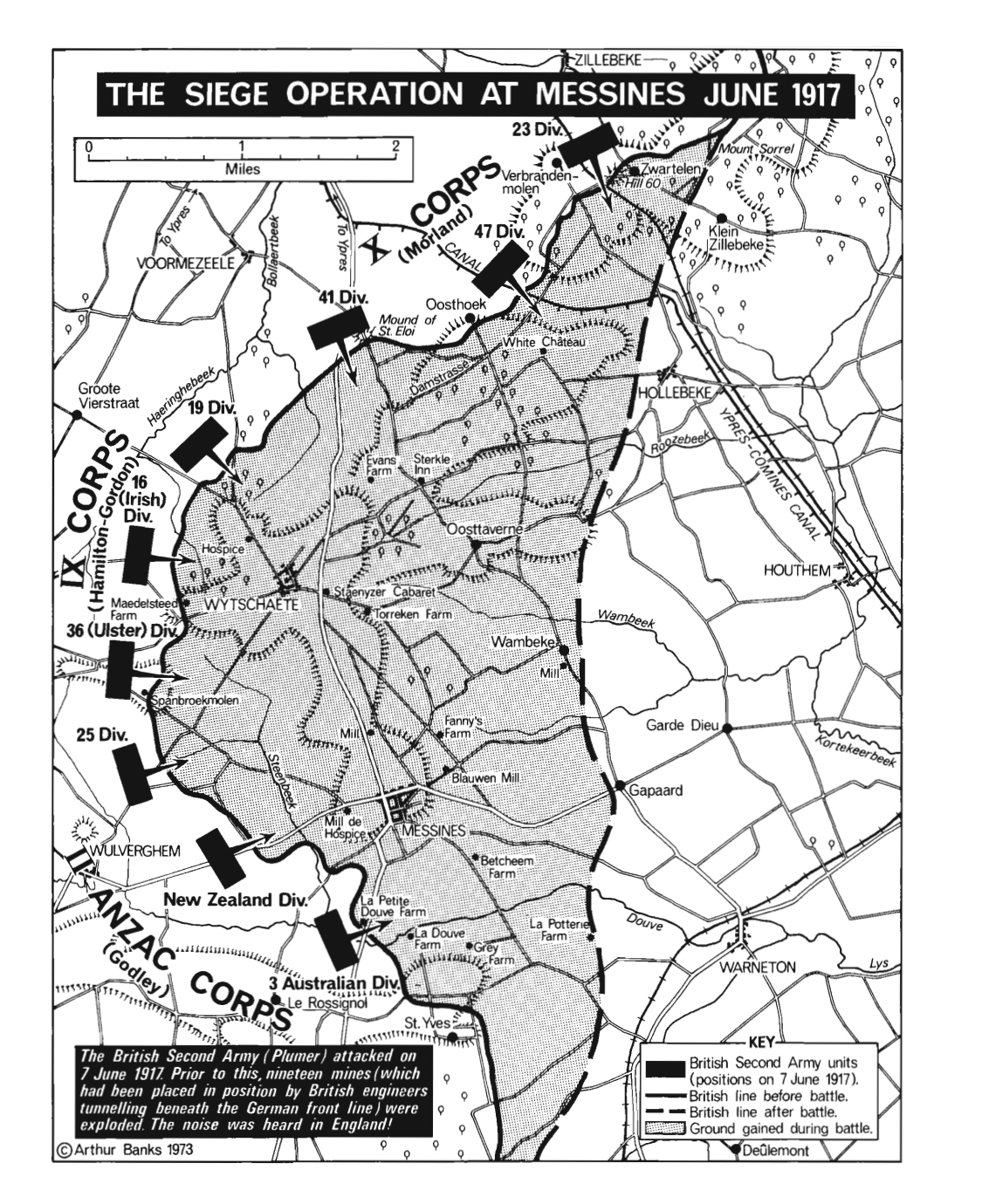

The attack on the Wytschaete-Messines ridge was a limited ‘bite and hold’ operation designed to clear the southern flank of the forthcoming Third Battle of Ypres. Messines was meticulously planned by General Herbert Plumer, who had taken to heart the key lesson of the Somme, that careful rehearsal and comprehensive planning were even more important than massive artillery bombardments. Plumer kept a firm personal grip on every possible aspect of his operation, from the barrage plan to the co-ordination of the mines, and from the water supply to the new backpacks used to take supplies to the front. The Australian general John Monash once famously said that trench warfare was ‘simply a problem of engineering’, and the battle of Messines, at which he was present as a division commander, was doubtless the sort of thing that he had in mind.

Plumer certainly believed in overkill, with some three million shells being fired during the two-week preliminary bombardment that was designed not only to break the Germans’ wire, but even to starve out their front-line infantry by preventing supplies being moved up to them from the rear. Then these supposedly starved troops would be blown sky-high by the simultaneous detonation of massive interlocking mines. The effects of the shock waves were to be multiplied as they rebounded off each other, and in the event as many as some 10,000 Germans were killed. The explosion could be heard in London, 130 miles away. Then a comprehensive creeping barrage began immediately and the attacking infantry captured the crest of the ridge along the whole of the attack frontage, at small loss. Casualties slowly mounted as the Germans gathered their wits and launched counter-attacks during the following days, complete with ground attack aircraft, but overall the battle had been a remarkable demonstration of Plumer’s tactical virtuosity.

Unfortunately the same could not be said of the early stages of the next battle, which was to be a much larger offensive out of the Ypres salient and Nieuport. One of the problems was that the operation had multiple aims, the incongruous first of which was to help the Royal Navy by capturing enemy naval bases on the Belgian coast. A major bridgehead across the mouth of the Yser Canal was to be set up opposite Nieuport, from which a drive on Ostend and Zeebrugge could be launched in conjunction with amphibious landings. However, while the bridgehead was still garrisoned by only one brigade, the Germans very cleverly counter-attacked and wiped it out. It soon became clear that the whole coastal wing of the British offensive would have to be abandoned. If Ostend were to be captured at all, it would have to be taken by an overland thrust of almost thirty miles due north from the Ypres salient, rather than the ten miles north-east from Nieuport. This was, of course, very much further than had been achieved by any offensive on the Western Front since 1914. Even if the rail junction north of Roulers (Roeselare) were accepted as a compromise or intermediate target, it was still twelve miles northeast from Ypres, and in a divergent direction.

As if this confusion were not bad enough, a number of other conflicting aims were also jostling for attention. One was the tactical consideration that the best way to clear the Germans away from the Ypres area was to capture the Gheluvelt plateau to the east of the city, in the direction of Menin, which was commanding high ground. Thus Haig found he had three possible directions for his thrust – towards Ostend, Roulers or Menin – which was of course no more than the logical result of starting in a salient where the enemy occupied almost three out of the four points of the compass.

It was certainly Haig’s duty to select one out of the three possible directions for his attack, and explain clearly to his subordinates exactly what the aim was intended to be. Alas, he failed to do either, but retreated into veiled talk of secret ‘higher considerations’ which prevented him from explaining his master plan. This has often been taken as a reference to the need to draw German attention away from the French mutinies, at a time when he felt he could not state out loud that they actually existed, in the same way that the Somme had relieved the pressure on Verdun in 1916. Modern research apparently rejects this interpretation of both 1916 and 1917, although of course Haig always saw it as his duty to fight alongside his French allies. Linked to all this, in Haig’s mind there must also have been some sort of theory of attrition, or ‘putting pressure on the Germans’, which in turn implied ‘seeking to fight frontal battles with as many of them as possible’, thereby ‘killing as many of them as possible’. This, of course, was a totally different objective from the idea of making a clean and deep breakthrough to Ostend, or Roulers, or across the Gheluvelt plateau. In all his battles Haig invariably retained some ultimate faith in at least the possibility of such a breakthrough, although he never actually managed to achieve one. In the particular case of Third Ypres it meant that he appointed the cavalryman Gough to command the major part of the battle, while Plumer, the more methodical expert in ‘bite and hold’ operations, was left in a secondary role.

There were thus considerable uncertainties within Haig’s planning staff. In which direction should they attack, and should they go for a breakthrough or a limited objective? In the event an ingenious compromise was agreed, whereby a whole series of ‘bite and hold’ attacks would be mounted in quick succession, hopefully at three-day intervals, until perhaps a final decisive breakthrough might be achieved. As for the direction, it was optimistically believed that because the attack frontage would be so long, and the attacking troops so numerous, all the various different objectives could be captured, and so every point of the compass could be covered. It might even be said, with the benefit of hindsight, that if only the battle had started a month earlier, and if only the weather gods had bestowed a little bit more luck upon it, it just might have worked.

Behind all this, however, is the much darker question of why Haig should have chosen to fight at Ypres at all. Even if we accept that he absolutely had to fight a major battle somewhere – to relieve the French or even to make a breakthrough all the way to Berlin – we are still free to question his precise choice of battlefield. His battles around Arras had only just finished in May, so we can understand why he might not have wished to return to the charge in that particular area. Nor had he personally any good memories of the sector facing Lille, between Vimy and Armentieres. Conversely, however, he must surely have treasured warm memories of his own personal triumph at the first (defensive) battle of Ypres in 1914. For Douglas Haig himself, the Ypres salient must have seemed almost like a benign environment, even though it was a notoriously malevolent one for those who had to actually live in it. Not only was it surrounded and overlooked on three sides by the enemy, and especially by his artillery, but it was a notoriously damp and muddy site in its own right. It had already won a particularly evil reputation among the rank and file of the BEF during Haig’s first battle in 1914, which was not at all improved by the frightening German use of gas in the second battle in 1915.

There was, however, another potential site for the great midsummer offensive of 1917, which with today’s hindsight we can suggest would have been considerably better than Ypres. This was the Cambrai sector, to the south of Arras, where the British were not in a salient and where the well-drained ground had not been churned up by years of shell fire. Admittedly it was a sector in which the Germans were especially well fortified in their new Hindenburg Line, but they were extremely well fortified at Ypres too, so maybe there was no significant disadvantage in that respect. As it happens, Cambrai would be the scene of a dramatic British success on 20 November, but by that time too many of the available resources had already been consumed in the Ypres salient. The Cambrai battle – really it should be called little more than a ‘raid’ – could not be sustained for more than ten days. We may speculate that if only the main weight of the BEF had been deployed to Cambrai in midsummer, the overall level of success might have been very much higher than it actually was.

The reality, however, was that Haig had committed himself un- shakeably to Ypres as the site of his main battle of 1917. Ideally it should have started very soon after the preliminaries at Messines in early June, but in fact it was delayed, for a variety of reasons, for over a month. The bombardment did not start until 18 July, at which point the Germans sprang their first nasty surprise, in the form of a counter-battery bombardment using their new blistering agent, mustard gas. The British artillery had to struggle against this horror at the same time as it was trying to suppress the German artillery, so naturally its efficiency was reduced. Finally the infantry went over the top on 31 July.

The first ‘bite and hold’ operation went very well over ground that had been thoroughly prepared by the artillery. However, it was found that the Germans had very strong positions in great depth, including many concrete bunkers, and it was only their forward outposts that had been captured. Then it began to rain, and the rain did not stop before the battlefield had been turned into a total quagmire. The preparations for the second ‘bite’ were delayed, and it turned out to be far less decisive than the first. The artillery could not move forward as quickly as planned; the tanks bogged down unless they stuck to the roads; many of the infantry weapons became jammed with mud, and the Germans were remorseless in their counter-attacks. The initial optimism for a rapid advance started to fade away. As the days ticked by criticisms of Gough’s methods began to mount, until at the end of August Haig eventually restricted the frontage for which he was responsible, and brought in Plumer to impose the strict organization and planning that had served him so well at Messines.

Plumer Takes Over

At this point the rain stopped and the sun once again began to shine, but for the next three weeks the British were unable to exploit the dry weather. Plumer was reorganizing the assault forces, so the offensive was temporarily halted. It resumed on 20 September in grand style, with a succession of three textbook ‘bite and hold’ attacks, culminating at Broodseinde on 4 October. Of particular note was the inability of the German counter-attacks to make progress against the massive weight of British artillery fire. Whatever tactics the Germans attempted to employ, they appeared to be powerless in the face of this dominant arm. It was exactly how Haig’s battle had been supposed to run in late June, and British spirits rose just as German optimism dissolved. However, it was now autumn moving into winter, and the rains began again, never to relent. In the long weeks after the heady success of Broodseinde the battlefield reverted to a heavily cratered bog, in which men could easily drown if they strayed away from the all too few duckboard paths. Depression and frustration set in as even the most normal operations became practically impossible. The Gheluvelt plateau was never totally captured, although the village of Passchendaele, at its summit, was captured by Canadian troops on 6 November, after which the whole operation was soon closed down. The allies had got nowhere near either Roulers or Ostend, and the cavalry Corps de Chasse had long ago been sent back to its stables.

The name ‘Passchendaele’ has entered the English language and consciousness as a symbol of the same type of futile sacrifice as was perceived to have occurred on the Somme a year earlier. However, in this case there were some added horrors which seemed to make the whole experience even worse. The most obvious was the rain and the all-pervasive mud, which the British public soon came to understand in a very vivid manner when the photographs were published after the war. The moonscape of shell craters filled with water, and devoid of all vegetation, made a very powerful impression. The very name ‘Passchendaele’ is itself resonant of squelching through deep, slimy mire.

Less well understood were some of the other horrors that were seen for the first time in this battle. Mustard gas was the first, and it was probably the nastiest gas of the entire war. The systematic use of concrete pillboxes by the Germans might be seen as another, in the sense that they made it much harder than previously to knock out or neutralize an enemy machine gun post. A third horror, widely noted in the memoirs of participants, was what in modern parlance is called ‘the deep battle’, or the ability to reach deep behind enemy lines with firepower delivered by artillery and aircraft. Before Third Ypres the troops knew that they were almost totally safe from attack as soon as they had moved a couple of miles back from the front line. In the second half of 1917, however, this could no longer be relied upon. In particular the techniques of night bombing had become more advanced. Soldiers sleeping ten miles behind the front now found they were likely to be woken up, and perhaps even killed, by air raids. At the same time truly long-range artillery was available in ever increasing numbers and on the British side, at least, the science of first-round accuracy (‘predicted fire’) was being perfected for its use.

Many different sub-sciences had to be brought together before a gun could be relied upon to hit its target with its first shot. The weather had to be studied at every altitude through which the shell would travel. The firing characteristics of each individual gun had to be exactly known, especially since they were constantly changing as the barrel wore out. Each batch of shells was also subtly different from every other batch, and these differences had to be fully understood if their line of flight was to be predicted. Precise and detailed mapping was especially vital, to establish the locations of both the firing gun and its target. To achieve this it was necessary to set up a vast network of aircraft taking photographs of the terrain on a daily basis; laboratories to process and interpret the photographs; workshops to convert the data into an accurately surveyed set of maps; and finally a printing and distribution system to get the maps to the guns and the tactical air photos to the infantry. During some operations new sets of maps and photographs had to be issued daily, as the situation on the ground kept changing. There was also a need for certain specialized techniques for locating enemy gun batteries, such as flash spotting or sound ranging. All this was enormously more sophisticated than anything that had been known before the war, and it amounted to a significant step forward in the ‘art of war’.

Apart from anything else, the new artillery techniques meant that guns no longer needed to be pre-registered by the lengthy old methods of trial and error. In the past, this prolonged process had always given away the presence of the guns many days before an attack was launched, which in turn was a key intelligence indicator that an attack was imminent. An attacker was unable to achieve surprise, however well he might camouflage the build-up of his troops, so the defender had every opportunity to concentrate his reserves at the key point. With the new techniques of ‘predicted fire’, by contrast, the guns needed to support an attack could be kept hidden and silent right up to the moment when the infantry climbed out of its trenches and began its assault. The enemy could be kept in total ignorance of the impending offensive until about two minutes before it arrived on his forward positions.

This represented a revolution in tactics, which came to be understood by the British high command soon after the battle of Third Ypres had begun. Obviously by that stage it was already far too late to achieve surprise at Ypres itself, but General Byng, commanding the Third Army further to the south, realized that he had an ideal opportunity to do so on his frontage facing Cambrai. He devised a plan of attack, based around a surprise artillery bombardment using ‘predicted fire’. Tanks were not originally part of this plan, as many have subsequently claimed, but they were added only later as an afterthought, to help crush the wire. The attack was carefully prepared in total secrecy during the first three weeks of November, and achieved total surprise when it was finally unleashed in the dawn mists of 20 November.

Despite the great strength of the Hindenburg Line defences, the assault troops rolled forward in splendid style. Most of the German artillery was knocked out almost instantly by accurate long-range fire; the wire was crushed under the tracks of some 378 tanks, and the infantry quickly occupied the enemy’s front-line trenches. Only in front of Flesquières, in the second line of defence, did the attack encounter stiff resistance. The leading tanks had the misfortune to encounter a specialist battery that had been trained in anti-tank tactics, and were shot to pieces as they climbed up the slope. For all their strengths and shock value, Flesquières demonstrated that tanks were far from invulnerable to enemy fire, and in fact during the day as a whole no fewer than sixty-five were knocked out. A further 114 were immobilized by mechanical problems or bogging, so the attrition rate was running at around 50 per cent per day of combat. Another major problem was that the build-up of carbon monoxide and petrol fumes within each tank, especially when combined with motion sickness, severely limited the time its crew could continue in action. Six hours was a very good average; eight hours was absolutely heroic. When advancing carefully over a broken and complicated battlefield, this factor greatly restricted the distance a tank could advance in a day from its starting point, which would itself necessarily be some way behind the infantry’s start line. In the case of Cambrai some tanks managed to advance as far as five miles into enemy territory on 20 November, but many more went much less far.

In the conditions of the Great War the tank could never possibly be considered a weapon of breakthrough. It had very limited range and speed, not to mention many other important tactical limitations. What it achieved at Cambrai was a great political triumph, in that at long last there were hundreds of tanks on the battlefield, rather than just a few dozens, and the progress made on 20 November was spectacular in the context of the Western Front. The church bells were rung in Britain upon receipt of the news, and the ‘myth of the tank’ entered the popular consciousness. The future of tank development and funding, which had been controversial ever since Bullecourt in April, was assured. The responsibility for making a breakthrough nevertheless remained firmly where it had always resided – with the horsed cavalry.

On 20 November it was the cavalry that was supposed to break through ‘to the green fields beyond’, and ultimately capture Cambrai itself. However the wide St Quentin Canal lay across the path of their intended advance, and by the time they got there only one rickety bridge remained. Some of the cavalry got across and established a bridgehead; but the whole impetus of their forward charge had been wrecked. The Germans were granted time to bring up reinforcements and make a fight of it after all. This meant that the successes of the first day, which had certainly been great, would lead to no breakthrough but only a new round of attritional trench warfare. It became focused on Bourlon Wood, a hill feature overlooking the whole battlefield from the north. The British finally took it on 23 November, only to lose it again on the 27th. At this stage of the battle Byng had run out of reserves, since his operation had only ever been conceived on a relatively small scale when compared with the major offensive that had just finished at Ypres. Indeed, he now found he had perilously few troops left to defend the ground he had won.

The Germans duly exploited the British weakness by mounting two major counter-attacks on 30 November, of which the one towards the south-east flank of the British salient was particularly effective. Much of the ground captured on the 20th was retaken and the balance of casualties, which had previously been heavily in favour of the British, was restored almost to equality. For the British it made a disappointing end to a battle that had started so well. For the Germans it demonstrated that in favourable circumstances they could still land well-prepared offensive blows with infantry spearheads following a hurricane bombardment. At Ypres the British artillery had been too strong and the terrain too broken for this tactic to work; but at Cambrai it worked well and pointed the way to a series of successful offensives in spring 1918. Nevertheless, the overall result at Cambrai was something of a drawn match. The breakthrough that had eluded tacticians in 1916 thus continued to elude them right to the end of 1917.