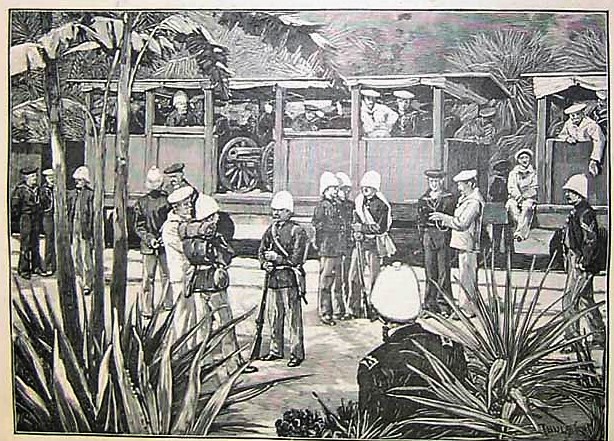

US Marines taking charge of the trans-isthmus railway (Note Gatling gun) 1885

The Mannix Mission to China, 1881-1884

One of the most influential Marine Corps officers to serve during the Gilded Age was First Lieutenant Daniel Pratt Mannix. A graduate of the U. S. Army’s Artillery School at Fort Monroe, Virginia, (1878), as well as the Navy’s Torpedo School at Newport, Rhode Island, First Lieutenant Mannix shortly thereafter volunteered to serve as a foreign instructor to the Imperial Chinese Navy in Taku near the Peiho River. While at Taku, First Lieutenant Mannix established a School of Application “modeled after our Artillery School,” where the students studied strategy, “grand tactics” or military operations, torpedoes, musketry, artillery, mathematics, and military history-in effect, all of those subjects thought necessary to better prepare a naval (or Marine) officer for war. Mannix put his education at the Artillery School and his experience in China to good use when he returned home in 1885 after serving the customary two years at sea as an instructor at the newly organized Marine School of Application, established on 1 May 1891 by the acting Colonel Commandant Charles Heywood.

Geography: Mitchell’s Geography and Atlas

Military History: Jomini’s Art of War, Weber’s Outlines of Universal History

Tactics: Robert’s Handbook of Artillery, Heavy Artillery, Light Artillery, Army Regulations

The curriculum Mannix studied at Fort Monroe and later instructed in China served as the basis for the one later adopted by the Marine Corps’ School of Application (1892) and the Advanced Base School established at Newport, Rhode Island, in 1910.

Captain Mannix later served as an assistant to Colonel Heywood who, as the health of the Colonel Commandant Charles McCawley began to fail, had some influence on Heywood’s reform movement of the Marine Officer Corps. Captain Mannix became the school’s first director, and suggested that this new school of application should “embrace training in electricity, torpedoes, gunnery, and drill for both officers and enlisted men.” There is evidence to suggest that Major Robert W. Huntington, one of the Corps’ most vociferous advocates of reform inside the officer corps, was also an advocate of professional education. While commanding the Marine Barracks in Brooklyn, New York, Huntington approved the applications of Second Lieutenants Leroy Stafford, Eli K. Cole, and Clarence L. Ingate, all of whom had applied for the Army’s School of Application for Cavalry and Infantry at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, but were ordered elsewhere. While Colonel Heywood disapproved the orders for the three young officers, writing that their services were “needed elsewhere,” one can deduce from this and other comments made by Major Huntington that he recognized that the Marine Corps lacked a second-tier professional school dedicated to the advancement of new officers. Huntington was one of the Corps’ most vocal advocates for bringing younger, more fit (and possibly more intellectually robust) officers into the Marine Corps. Huntington admitted that the Marine officer corps had become “old and tired,” because most of its senior officers (and some company grade officers) had been commissioned at the time of the American Civil War. The Marine officer firmly believed what the Corps needed was nothing short of a “transfusion of new blood into the officer corps.” Major Huntington recognized that if the Marine Corps was to modernize, it would have to change its institutional structure and how it educated and trained its newly commissioned officers. Despite Mannix’s death on February 6, 1894, the School of Application went on to serve as the basis for the education of Marine officers and non-commissioned officers that was, in time, expanded and improved upon. Mannix’s reforms and the introduction of the course of study he developed while in China served the Marine Corps for the next three decades (1890-1920).

Esmeralda – the world’s fastest cruiser in 1884

Trouble on the Isthmus, 1885

On April 2, 1885, after months of political turmoil on the Isthmus of Panama due to the overthrow of the constitutionally elected government, Secretary of the Navy W. C. Whitney ordered Colonel-Commandant Charles G. McCawley to “detail a battalion of Marines to sail the next day on the City of Para for Colon.” Secretary Whitney instructed Rear Admiral James Jouett, commanding officer of the North Atlantic Squadron, that the mission of the Marines and bluejackets was to “open the transit on the isthmus and protect the lives and property of the Americans (and other foreigners) living there.” In turn, Rear Admiral Jouett instructed Lieutenant Colonel Heywood to “proceed to Panama with the battalion of Marines under your command, for the protection of American lives and property in that vicinity…. Panama is now in the hands of the revolutionary forces, and it is feared that if the place is attacked by the regular Colombian troops these revolutionaries will attempt to destroy the city, or portions of it, by burning. As the burning of Panama would involve the destruction of much American and other foreign property, you will prevent it if possible.”

Action in Panama, April-May 1885 After assembling Marines from the various barracks along the eastern seaboard, Heywood’s First Battalion set sail on the City of Para, a requisitioned steamer, and headed south for Colon. This first battalion of Marines (soon to be joined by a second, commanded by Captain J. H. Higbee) arrived in Panama in the early evening hours on April 11, 1885, and shortly thereafter disembarked from their makeshift transport. With the city in turmoil, Colonel Heywood’s Marines occupied strategic locations throughout Colon. As Marines of the First Battalion spread throughout Panama, Captain R. W. Huntington’s Company A, Second Battalion, was ordered by Commander Bowman H. McCalla, commanding officer of all naval forces on the Isthmus, to “proceed to Matachin, in a special train that will be provided by the Panama Railroad Company to follow the 3 P. M., with the company now under your command, and relieve Lieutenant Impey and the garrison now at that place. I have directed the commanding officers of a section of artillery and a Gatling gun to report to you as part of your command. Your duty will be to keep the transit open, to protect the lives and property of American citizens, and to have your command in the highest state of efficiency…. Take with you three thousand rounds of ammunition in excess of what has been served out.” Shortly after receipt of this order, Huntington moved out toward Matachin, where his company took up positions to defend the railroad and other vital sectors of the town.

Captain Huntington’s Marines-loaded down with two days’ rations, a breech-loaded rifled musket, forty cartridges, rolled blanket, two canteens, a haversack, and a change of clothing, and supported by a 3-inch rifle as well as Gatling gun with sufficient ammunition- boarded a special train that took them to Matachin. Commander B. H. McCalla, who was in command of the transport carrying Huntington’s Marine battalion thirteen years later off Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, informed the Marine captain that his mission was “to keep the transit open, to protect the lives and property of American citizens, and to have your command in the highest state of efficiency.” Assisted by First Lieutenant George F. Elliott, Second Lieutenant Carroll Mercer, and Navy Lieutenants (j. g.) J. C. Colwell and Alexander Sharp, along with fifty-two enlisted Marines and fifty bluejackets, Huntington’s mission was to essentially “ride shotgun” and keep the rail lines open.

Upon hearing the news that the Colombians were prepared to march on Colon, Admiral Jouett ordered the occupation of Colon. As the two Marine battalions and accompanying platoon of Navy bluejackets marched in three columns to engage the revolutionaries, the force split into three columns, each assigned a district of Colon in order overwhelm and neutralize the enemy. Lieutenant Colonel Heywood, who had established his headquarters in Panama, proceeded to carry out Admiral Jouett’s orders. For the next three weeks, Marines and bluejackets skirmished with revolutionaries, and arrested and herded them into detention areas placed near the U. S. Consulate. To guard these prisoners Heywood assigned a detachment from Huntington’s Company A.

Lieutenant Colonel Heywood shortly thereafter received orders from Admiral Jouett to prepare his forces for the evacuation of Panama. On May 7, 1885, after the arrival of three hundred Colombian troops, Lieutenant Colonel Heywood’s First Battalion boarded the City of Para and the other ships that accompanied the Atlantic Squadron to Panama and set sail for the east coast of the United States. Meanwhile, to protect the U. S. Consulate and other American interests in the area, Admiral Jouett retained a small detachment of leathernecks from the USS Shenandoah in Panama to guard the trains and maintain order. By May 25, sufficient order had returned to Panama to allow the withdrawal of this small force, which soon re-embarked aboard the Shenandoah, though the ship remained in Panamanian waters for some time to come.

The landings in Panama are significant in that it was, to date, the largest single force of Marines assembled for a military operation ashore since the landing at Fort Fisher during the American Civil War. The rapid assembly of Lieutenant Colonel Heywood’s force of 34 officers and 651 enlisted Marines, tactically organized into a brigade and augmented by Navy bluejackets, was in and of itself a remarkable accomplishment given the state of the U. S. Navy as it transitioned from sail to steam. In fact, the City of Para, a steam collier, had been contracted by the Navy to transport the Marines to Colon.

While it remains true that Marines saw this episode as part of their traditional role as part of the Navy, there was already a body of literature that suggested a permanent role for the Marines as a ship-borne expeditionary landing force. Even Rear Admiral Jouett indirectly pointed to this fact in his letter to Lieutenant Colonel Heywood, upon the latter’s departure from the Isthmus:

Your departure from the Isthmus with your command gives me occasion to express my high estimation of the Marine battalion. You and your battalion came from home at the first sound of alarm, and you have done hard and honest work. The Marine battalion has been constantly at the front, where danger and disease were sure to come, first and always. When a conflict has seemed imminent, I have relied with most implicit confidence on that body of tried soldiers. No conflict has come, but I am well aware how nobly and steadily, through weary and anxious nights, exposed to a deadly climate, the Marines have guarded our country’s interest. Please communicate to your command my grateful acknowledgment of their faithful service on the isthmus of Panama, and accept my sincere thanks for your earnest and valuable assistance.

As for Captain Huntington’s services while commanding Company A of the Second Battalion, Commander McCalla cited the Marine officer’s efficiency, and added that he had “formed a high opinion of while serving at Matachin,” as he had performed his duties there in a most “satisfactory manner.”

The expedition to the Isthmus held out the prospect that the Marine Corps did, indeed, have an important role to play in the Navy’s transformation and in the United States’ more aggressive foreign policy. Unfortunately, internal politics and an officer corps that was for the most part unfit for field service hindered the Marine Corps’ ability to capitalize on the lessons learned during the Korean and Panamanian interventions or the reforms in officer education as advocated by Lieutenant Daniel Mannix. In fact, it would take five years for the Marines to act upon the creation of a School of Application for all new second lieutenants. Finally, it took twenty-five years for the Marines to establish a school for advanced base work at Newport, Rhode Island, in 1910.

Yet there were positive results of the Panamanian intervention that were unforeseen at the time. The most important of these was relationship established between Captain Huntington and Commander McCalla. Both men would meet again during the War with Spain when McCalla’s transport, the Marblehead, would transport then Lieutenant Colonel Huntington’s Marine battalion ashore on June 10, 1898, to Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. Finally, the intervention on the Isthmus demonstrated the need for a “floating Marine battalion,” something that would not come about until after the War with Spain. The fact that Marines were not centrally located but spread up and down the East Coast at the various Marine Barracks meant that any intervention would have to be delayed until the forces assembled at either Philadelphia or Norfolk and were transported to where they were needed. While this situation was acceptable in dealing with rebels such as the Koreans or Panamanians, against a major military power (like Spain) it was a different story, for it could be very costly in terms of surprise or military effectiveness.

Despite the inability of the senior Marine leadership to peer into the future, the seeds for future successes had been planted. While Marine officers concerned themselves with promotions and internal reform, thoughtful Navy officers began to articulate the view that with the growth and development of the New Steel Navy, and the transition from sail to steam, there was a need for a landing force to accompany the fleet in time of war to seize and defend advanced coaling bases in distant waters. It was left to the War with Spain for Marine officers to “see the light” insofar as this new mission was concerned.