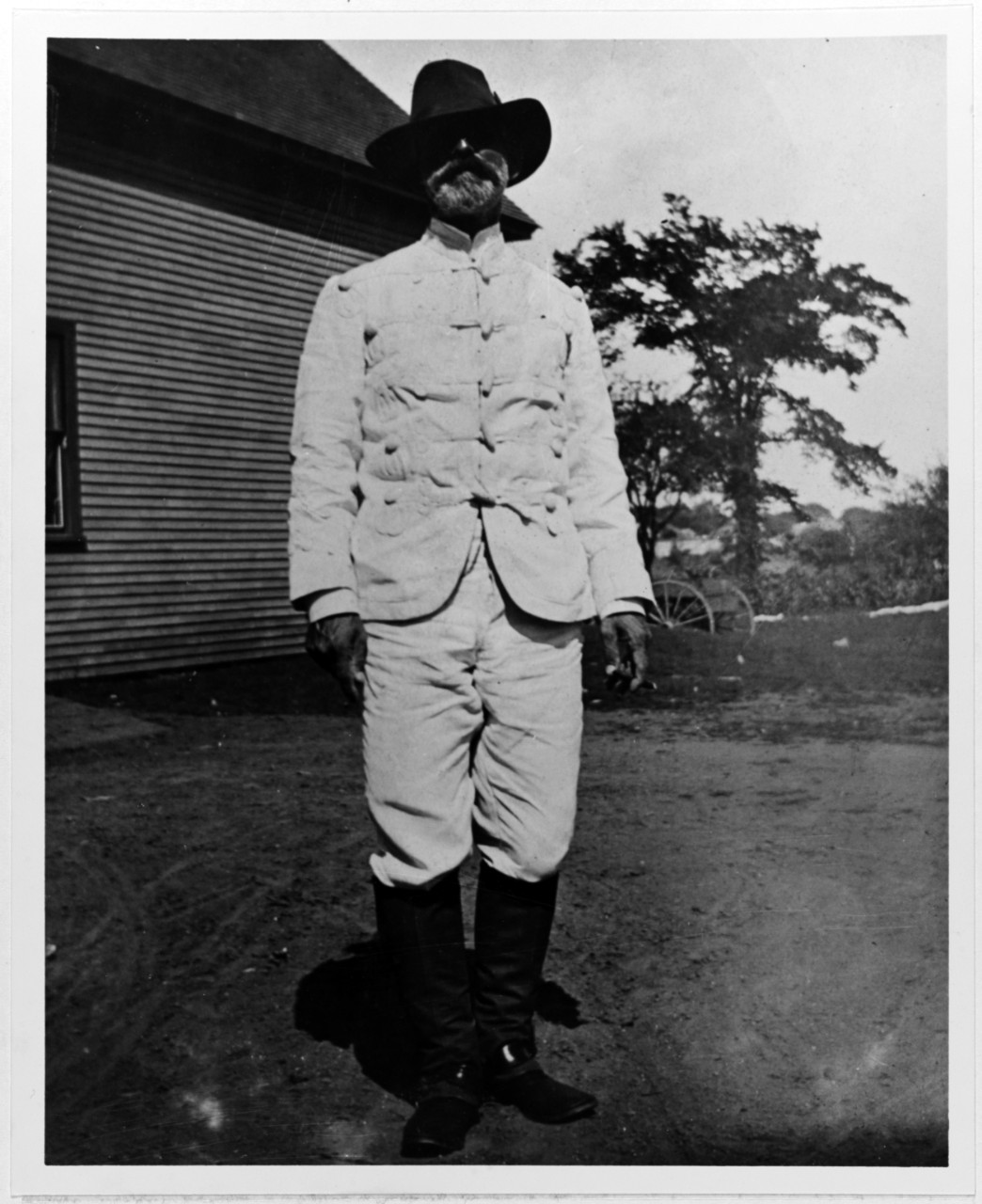

Colonel Robert W. Huntington

USMC While Colonel Robert W. Huntington had been long since retired when Marines carried out a series of maneuvers later dubbed “Advanced Base Force” exercises from 1903 to 1907, his landing at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, during the War with Spain in 1898 laid the foundation for the growth and development of the Marines’ landing doctrine during the 1920s and 1930s. Also, when Huntington’s career as a Marine officer began at the commencement of the War Between the States in 1861, a transformation was already underway insofar as the development of ironclad ships that would eventually lead to the birth of the New Steel Navy in the 1880s and inevitably affect the mission of the Marine Corps. While Huntington’s military career followed the normal pattern of sea and shore duty for Marine officers during the “Gilded Age,” technical and professional changes inside the Navy and Marine Corps ultimately led the latter service to embrace the mission as an expeditionary force-in-readiness during the early twentieth century.

While Colonel Huntington had very little directly to do with the development of the Advanced Base Force, everything he did in his career after the Civil War-including the landings during the American Civil War at Port Royal in South Carolina, off Hatteras, North Carolina, in November 1861, the landing in Panama in 1885, and a humanitarian mission in Apia, Samoa-pointed the Corps’ to its future missions. Despite the outward appearance that the Marine Corps had grown anachronistic there were events ongoing inside the Navy that directly or indirectly impacted that service during the last quarter of the 19th through the early part of the 20th centuries. Thus, through the examination of the career and era of Colonel Robert W. Huntington, one can clearly see the origins of the Corps’ future mission as an advance base force. There is little doubt that Colonel Huntington was the Marine Corps’s first expeditionary force commander.

Early Years, 1840-1865

Robert Watkinson Huntington was born on December 3, 1840, in West Hartford, Connecticut. After receiving his early education in West Hartford, Huntington entered Trinity College in 1860. On April 23, 1861, upon the outbreak of the War Between the States, he enlisted in the 1st Connecticut Regiment as a member of Captain J. R. Hawley’s Company B, a volunteer outfit comprised of young men from Hartford. While still a member of the 1st Connecticut, Huntington applied for and accepted a commission as a second lieutenant in the Marine Corps with the date of rank on June 5, 1861.

During the fighting at the First Manassas or Bull Run, Huntington commanded a platoon of Marines prior to the withdrawal of Union forces from the battlefield. Detached briefly from Reynolds’s Marine Battalion, Huntington led a unit assigned to guard and transport state prisoners from Washington and Annapolis to Fort Lafayette. While he was assigned to this duty, the Marine Corps, on September 30, 1861, advanced Huntington to the rank of first lieutenant. Detached from prisoner duty, Headquarters then assigned Huntington to the Navy’s Potomac Flotilla where, acting on sealed orders, he was to escort under armed guard a captured Confederate raider and deliver him to the commandant of the Washington Navy Yard. In October 1861, Headquarters re-assigned Huntington to the seagoing Marine battalion commanded by Major John G. Reynolds, then making preparation for the expedition to seize Port Royal, South Carolina. Although this battalion spent more time at sea than in conducting amphibious forays ashore, it nevertheless “participated in the most vital naval undertakings of the war-the great blockade of the South.” The Marine battalion in fact played a minor role in the Navy’s plan to seize several strategic sites in order to utilize them as advanced bases “as soon as adequate amphibious forces could be assembled.” Reynolds’ amphibious battalion was a small portion of the force gathered to conduct the planned assaults. While serving with Reynolds’ battalion, Huntington participated in the naval expedition led by Captain Samuel F. Dupont in the capture of Port Royal, South Carolina, and a landing with a company of Marines from the USS Mohican in the seizure and capture of Port Clinch near the town of Fernandina, Florida, in December 1861.

Lieutenant Huntington was detached from Reynolds’s amphibious battalion on March 31, 1862, and Headquarters Marine Corps reassigned him to the Brooklyn Navy Yard on April 3, 1862. He remained at the Brooklyn Navy Yard until ordered to command the Marine detachment aboard the USS Jamestown, then at dock at the Philadelphia Navy Yard. On May 26, 1863, the Jamestown departed Philadelphia and took up station with the Asiatic Fleet. For the next eighteen months, Huntington, now a captain, remained at sea. From 14 July to 5 August 1864, in response to the violence aimed against the foreign legations and diplomatic personnel in Japan, Captain Huntington took charge of a mixed force of Marines and bluejackets assigned to guard the U. S. Legation and U. S. Minister’s residence in Yeddo (Tokyo), Japan. After the violence subsided, Huntington’s detachment re-embarked aboard the Jamestown and proceeded to Mare Island, California. In October 1865, Huntington reported to the Brooklyn Navy Yard to answer charges to a court of inquiry then investigating alleged mistreatment of the enlisted men under his charge during his tenure as commander of the Jamestown’s Marine detachment. At the completion of the court of inquiry, Huntington left for a brief period of leave and re-resumed his duties as assistant commander of the Brooklyn Navy Yard from November 1865 to April 30, 1866, at which time he reported for duty at the Portsmouth, N. H., Navy Yard.

Assault from the Sea: The Civil War and Amphibious Warfare

The strength of the Marine Corps never went beyond 3,773 officers and men during the Civil War, but Marines were present during several important operations that were a forerunner to its advanced base mission during the first two decades of the 20th century. The majority of operations classified as classic amphibious operations during the Civil War, were, however, carried out by the Army. While historians have correctly characterized these landings as minor operations with little or no tactical or operational significance, they were nonetheless important from the strategic point of view in that the landings were part of the Union plan to draw Confederate forces away from Richmond and thereby assist General Ambrose Burnside’s stalled offensive on the Peninsula, and to harass and if possible destroy the Confederate lines of communication in and around the Confederate capital. From 1862 through 1864, Union amphibious forays supported the main campaigns on land, with the most important one being General William T. Sherman’s “March to the Sea.”

As was the case with the majority of combined operations during the Civil War, interservice squabbling, rivalries, and institutional bickering derailed any benefit from these landings. Several of the most important operational “lessons not learned” by the Marines were those put forward during the landings at Port Royal, Fernandina, later at Roanoke Island (November 1862), and Fort Fisher, North Carolina (December 1864). During the last decade of the 19th Century when Headquarters Marine Corps established the School of Application for all newly commissioned Marine officers (1891), the landing operations carried out by the Army during the Civil War remained forgotten and insignificant to Marine officers, many of whom remained fixated on the “traditional roles” performed by Marines (i. e., as ships’ detachments and landing parties). There was a loss of what today is termed “corporate knowledge” among the vast majority of Marine officers, and it is speculative whether retention or dissemination of this knowledge would have paid off on any future Marine Corps mission. The point remained that Marines, as the War with Spain demonstrated, had to re-learn the lessons of amphibious insertion in the decades to follow. The Marine Corps’ failure to embrace what was a potentially ideal mission as the Navy’s landing force meant that the mistakes of such operations as Hatteras Island (November 1861), Port Royal, S. C., Fernandina in December 1861, and Fort Fisher would be repeated. Inept strategic and tactical leadership as well as overambitious planning hampered the U. S. Marines (and the Navy and Army) throughout the war. Perhaps the greatest contribution made by the Marines during the Civil War was aboard the ships of the Navy. Here, Marine detachments served as gun crews that bombarded the Confederate forts along the East and Gulf Coasts. Nevertheless, the War Between the States produced several lessons insofar as amphibious operations were concerned. The most important of those were the assaults on New Bern, N. C., and later Fort Fisher, N. C. For the most part, however, Marine officers failed to see the significance of those landing operations and how they could use them to redefine the role and mission of the Marine Corps during the last quarter of the nineteenth century.

Marines in the Gilded Age: Duty Ashore and at Sea, 1865-1885

At the conclusion of the war, Huntington, now a captain, served in billets ashore and afloat in a Marine Corps beset by manpower reductions, low morale among both officers and enlisted men, few officer and enlisted promotions, a high desertion rate and, most importantly, the lack of a defined mission. Despite the institutional crisis affecting the Marine Corps, however, there was on the horizon both a mission and a role that would define the Marine Corps for the next century and half. Contrary to the contention that the period from 1865 to 1898 was the Corps’ least active insofar as its institutional growth and expansion was concerned, the era was instead the commencement of the Corps’ renaissance as a fighting force.

All was not bleak during the Gilded Age, as Marines conducted several landing operations that held important lessons for their future missions. These operations were in Formosa (1867), Korea (1871), and in Panama (1885), and laid the groundwork for the Corps’ advanced base mission through the services of Captain Daniel P. Mannix to the Imperial Chinese court in the early 1880s. Captain Mannix’s attendance and training at the U. S. Army’s Coastal Artillery School at Fort Monroe, Virginia, in 1878, and his subsequent duties as an instructor in coastal defense, led indirectly to the establishment of the School of Application for all newly commissioned Marine officers in 1892 at the Washington Navy Yard and the subsequent advanced base force exercises in 1903. The lessons Mannix learned in China were later modified and taught during the early twentieth century at the Advanced Base School to a new generation of Marine officers who practiced them on the beaches of Culebra in Puerto Rico.

During the Gilded Age, Marine officers such as Captain Robert W. Huntington and others carried out missions that were to become standard Marine missions during the 20th century. These missions included diplomatic security, protection of American interests in Asia, South America, West Indies, and in the Mediterranean Sea, punitive expeditions, and the evacuation of noncombatants from troubled spots throughout the world. The landings in Formosa in 1867, Korea in 1871, and Panama in 1885, where Captain Robert W. Huntington commanded a company of Marines, led directly to the expeditionary assault missions carried out by Marines to this day.

A Punitive Expedition to Formosa in 1867

In response to the murder of the shipwrecked crew of the U. S. merchant ship Rover by the natives of Formosa, and in accordance with the accepted principles of international law concerning redress, the American Consul General C. W. LeGendre, the British Consul General, Mr. Charles Carroll, and the U. S. Minister to China ordered Commander John C. Freibeger, commanding officer of the USS Ashuelot, along with the USS Wyoming and USS Hartford, to proceed to Formosa. The U. S. Asiatic Squadron along with a landing force of one hundred and eighty-one officers, sailors, and Marines under the command of Captain James Forney set sail from a base in Hong Kong for Formosa (Taiwan) in order to punish members of the Botansha tribes who were responsible for this deed. On June 13, 1871, the leathernecks and bluejackets “fought desperately, burning a number of native huts, and chasing the warriors [who covered themselves in blue dye] until they could chase them no longer,” all at a heavy cost of men killed and wounded.

After disembarking from their ship’s boat, Captain Forney and the Marines under his command took positions ashore and formed into skirmish formation, then found themselves engaged in sustained fighting. In a report submitted to Commander Belknap after the Marines re-embarked aboard the USS Hartford, Captain Forney provided the commander of the Asiatic Squadron with a detailed description:

On the first landing, by your order, I took charge of twenty Marines, deploying them forward as skirmisher. A dense and almost impenetrable thicket of bush prevented the men from advancing very rapidly. I penetrated with them to a creek about half a mile from the beach without meeting any of the enemy, and was then recalled for further orders. You then instructed me to leave a sergeant and five men on the beach, and to advance with the main body, headed by yourself. In consequence of all further operations coming under your own observation, I have nothing further to report, except that the men behaved gallantly, and deserve credit for the manner in which they marched over such a rough and hilly country, and under such intense, scorching heat…. The entire number of Marines on shore was forty-three, thirty-one of whom were from this ship [Hartford], and twelve from the Wyoming.

By 4 o’clock that afternoon, the Marines and sailors who had chased the aborigines into the hills began to feel the effects of the hot Formosan sun and retired to the beach, where they boarded the ships’ boats and headed back to the ships of the Asiatic Squadron. After much difficulty General LeGendre was able to negotiate a treaty with the leader of the Botanshas, Tokitok, who agreed not to commit any more outrages against shipwrecked seamen. Retiring to their ships, the Marines and bluejackets set sail for their base in Hong Kong.

Lieutenant Colonel McLane Tilton, USMC

Tilton’s Landing in Korea in 1871

Upon receipt of orders from the State Department, in May 1871, the American Minister to China, Mr. Low, set out on a diplomatic mission to establish relations with the Kingdom of Korea, then under the tutelage of the Chinese throne. Accompanying the minister was Rear Admiral John Rodgers, Jr., Commander-in-Chief of the Asiatic Fleet, as well the 105-man Marine detachment commanded by Captain McLane Tilton. After assurances to the Korean officials that their intentions were peaceful, the American diplomatic mission proceeded up the Salee River. While a group of sailors made surveys and soundings of the Salee, the fortresses on the bank of the river opened fire on the Americans. While the Koreans wounded only two Americans, both Minister Low and Admiral Rodgers demanded an explanation and an apology for this attack. With neither forthcoming, Admiral Rodgers readied the fleet for action to storm and neutralize the fortresses. The admiral likewise readied the combined landing force of bluejackets and Marines. As U. S. Navy gunboats (USS Monocacy and Palos) towed the launches carrying the men, the guns from both ships fired on the enemy forts as the combined American assault force, led by Lieutenant Commander Casey, made its way toward the shore.

On Saturday, June 10, 1871, the boats carrying Captain Tilton’s battalion (105 officers and enlisted Marines) landed on a gently sloping beach two hundred yards from the high water mark surrounded by marshes and saturated with an ankle-deep, thick mud that made movement nearly impossible. After Tilton’s force struggled through the swampy terrain, the Marine officer deployed his force into skirmish order and began the tedious job of clearing the first of the offending forts. In what was perhaps up to that time one of the most successful examples of a combined Navy-Marine assault ashore, Captain Tilton’s Marines, supported by the Navy’s gunboats commanded by Commander Picking, fought their way for the next eighteen hours through a maze of fortresses heavily defended by fanatical Koreans. The Koreans, many of whom preferred death to surrender, fought the Marines with muskets, swords, spears, and rocks. Finally, after nearly two days of fighting, the last of the forts fell to the Marines and bluejackets. In his after-action report, Lieutenant Commander Casey praised the conduct of the Marines, who he said “were always in the advance, and how well they performed their part I leave to you to judge.” Commander Kimberly, who was in overall command of the operation ashore, added, “To Captain Tilton and his Marines belong the honor of first landing and last leaving the shore, in leading the advance on the march, on entering the forts, and as acting as skirmishers.”

In his report following the capture of the forts, Captain Tilton described the landings by his Marines on 10 June 1871:

On Saturday, 10 instant, the guards of the Colorado, Alaska, and Benicia, numbering one hundred, and five, rank and file, and four officers, equipped in light marching order, with one hundred rounds of ammunition and two days’ cooked rations, were embarked from their respective ships and towed up the Salee River by the United States ship Palos. Upon nearing the first of a line of fortifications, extending up the river on the Kang-Hoa Island side, the Palos anchored, and by order of the commanding officer all the boats cast off and pulled away from the shore, where we landed on a wide sloping beach, two hundred yards from high-water mark, with the mud over the knees of the tallest man, and crossed by deeper sluices filled with softer and still deeper mud. After getting out of the boats, a line of skirmishers was extended across the muddy beach, and parallel to a tongue of land jutting through to the river, fortified on the point by a square redoubt on the right, and a crenellated wall extending a hundred yards to the left, along the river, with fields of grain and a small village immediately to the rear.

While Captain Tilton’s actions ashore have been dismissed as insignificant to the Marine Corps’ gradual assumption of the advanced base force mission, they nonetheless represent one more important piece of the institutional puzzle that was a foundation for Huntington’s landing at Guantanamo Bay in 1898. While it is true that Tilton’s Marines remained ashore for only eighteen hours and that the landing was more of a punitive expedition and not an amphibious assault such as the one at Fort Fisher during the American Civil War in December 1864, the landing in Korea nevertheless represented one more step toward the Marine Corps’ advanced base force mission.

While this factor remained buried insofar as “lessons learned” at Headquarters Marine Corps, the work of Captain Daniel P. Mannix at the U. S. Army’s Coastal Artillery School (1876-78) and in China is a reminder that the Marine Corps did have a vital role to play in ongoing revolution in naval affairs that swept the country with the U. S. Navy’s acquisition of ships made from steel (the New Steel Navy) in 1883 and its evolution as a modern force. The landings in Korea in 1871 and the landing on the Isthmus of Panama in April 1885 pointed to the need for an expeditionary assault force schooled in the defense and seizure of advanced naval bases, and in the employment of torpedo and mines.