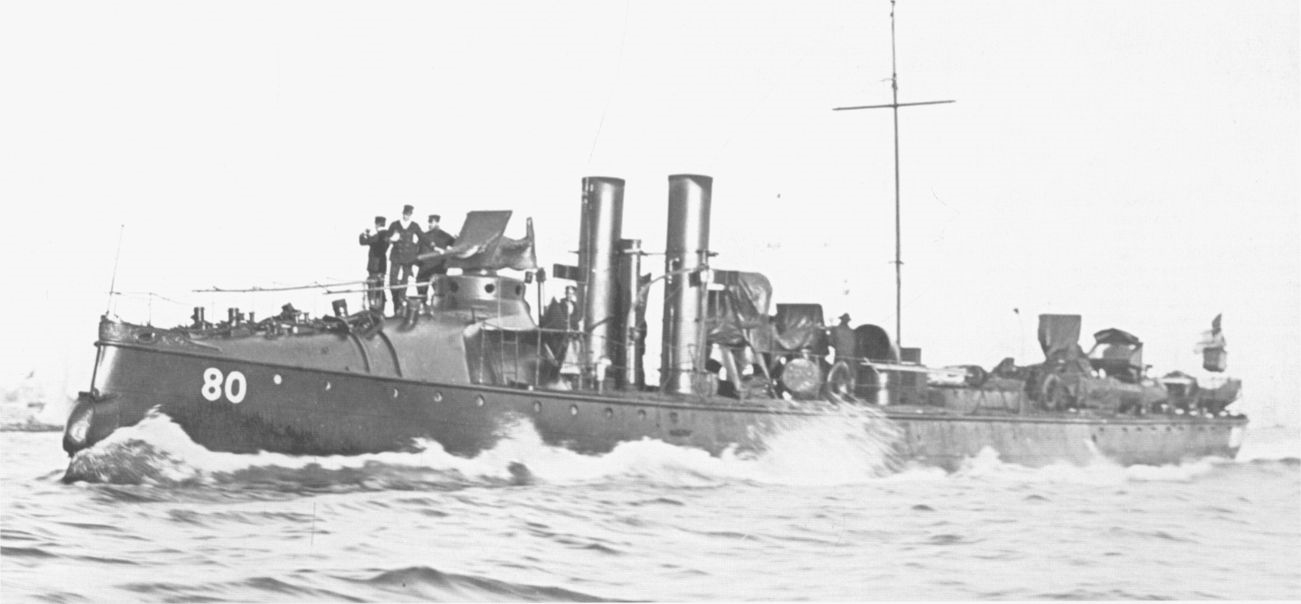

Yarrow’s TB 80

TB 82 was the production version of Yarrow’s turtleback TB 79. Although in theory boats were to be conned from the protected conning tower, it gave a poor view, and the after steering position was preferred (as evident here). Note the glass shield for the chart table. These boats were similar to TB 79, but with a turtleback. They proved weak in service, and had to be strengthened.

Yarrow’s TB 80, ordered in 1886, introduced the turtleback bow into British naval torpedo boat practice. She was based on Yarrow’s Falke for Austria (which also had a turtleback), with greater beam. Running the turtleback to the conning tower precluded the earlier practice of mounting two torpedo tubes alongside it. This design offered instead a single fixed bow tube (with two torpedoes); the Austrian boats had two bow tubes, one alongside the other. Note the 3-pounder gun atop the conning tower. In the alternative gunboat configuration, the two tubes alongside the after conning tower were replaced by a second gun. Two more 3-pounders could be mounted en echelon in the waist abaft the funnels (a written account mentioned a third gun on deck, but it is not visible in printed plans). A drawing showed both four guns and the two tubes, but it seems unlikely that all would have been carried at the same time. Other alternatives considered were five torpedoes and tubes plus one 3-pounder and two Nordenfelts or two 3-pounders or the bow tube (two torpedoes), two deck tubes, one 3-pounder and two Nordenfelts. Yarrow advertised this design as a ‘division’ torpedo boat, the term meaning that it could go to sea with a division of a fleet. In 1901 the armament of this boat was set as one fixed bow tube, two single deck tubes, and three 3-pounders (presumably she had been rearranged by then). Although TB 80 had two side-by-side funnels, she had a single locomotive boiler (working pressure increased from the 130psi of the first Yarrow 125-footers to 140psi of the previous type to 160psi). Dimensions were 135ft × 14ft (130 tons), with a bunker capacity of twenty-three tons (2700nm endurance at ten knots). A DNC document dated 24 July 1886 shows the originally proposed displacement as 105.2 tons, rising to 106.1 tons (with loss of metacentric height) with the proposed turtleback and the initially proposed armament. Lowering the conning tower saved some weight, and then conning tower thickness was cut from half-inch to three-eighths inch. That restored nearly all the original stability. On trials, TB 80 made 22.98 knots on 1539ihp at 101.75 tons (3ft 10¾in mean draught); rated power was 1600ihp. Falke in turn was based on Yarrow’s Azor and Halcon for Spain.

The Admiralty

The ships described were ordered by the Board of Admiralty. The First Lord was responsible to Parliament and thus to the Prime Minister of the day. He was broadly equivalent to the US Secretary of the Navy. In the 1880s, Boards generally also included a Civil Lord with some special naval knowledge. Civil Lords included George Rendel, formerly of Armstrong’s, and personally responsible for many export warships and also for introducing hydraulic machinery, and Thomas Lord Brassey, who in 1882 published the multi-volume British Navy (a call for naval reform) and who left in 1885 to begin publishing his Naval Annual. In 1884, Brassey was promoted to Permanent Parliamentary and Financial Secretary. As such he had to defend government resistance to the campaign for additional naval spending. From 1885, the Civil Lord was responsible mainly for civil works such as dockyards.

The naval members were led by the Senior Naval Lord, renamed First Sea Lord when Admiral Fisher took that post. His assistant or deputy (Second Naval Lord) eventually was responsible mainly for personnel. The Third Naval Lord or Controller was responsible for materiel (between 1870 and 1882, the Controller was not a Board member). At times, about 1900, the captain designated to become Third Sea Lord seems to have acted as Controller before being given that appointment (eg, Captains Fisher and May). The Junior Lord (typically a captain) ultimately became Fourth Sea Lord with special responsibility for supplies. Later a Fifth Sea Lord was added mainly for naval aviation. Under the Controller came the three principal materiel departments: Naval Construction (headed by the Director of Naval Construction (DNC), often also styled Assistant Controller), Naval Ordnance (DNO), and Engineering (ie, machinery, headed by the Engineer-in-Chief (E-in-C), normally an Engineering Rear Admiral). Typically the DNO was a captain, and the DNC was a civilian member of the Royal Corps of Naval Constructors (founded in 1883). The Controller laid out the Board’s requirements, and the DNC produced one or more alternative sketch designs.

In the 1880s, Britain was the foremost warship builder in the world. Private British yards built almost exclusively for export (Royal Navy ships were built mainly at Royal Dockyards, corresponding to US naval shipyards). The DNC recognised that small fast surface warships involved specialised design work. He felt comfortable with cruisers and larger ships, and with slower ships such as gunboats. Thus, for torpedo boats and then for destroyers, the DNC circulated broad requirements and monitored the designs submitted. The torpedo gunboats were an intermediate case. As destroyers grew, the gap between a scaled-down unarmoured cruiser and a scaled-up (and substantially strengthened) torpedo boat shrank, so that the DNC felt capable of designing destroyers. After 1909, he took over the destroyer design process, the results generally being called Admiralty designs. Even then the specialist builders were invited to submit alternative designs, particularly when the DNC or the E-in-C wanted to try special features. The A to I ships of the interwar period were all DNC designs. They were so successful that the major export success of the late 1930s was for modified Admiralty-designed destroyers.

Unlike the DNC, the E-in-C lacked in-house design capability. He recommended machinery features and monitored firms’ proposals. The E-in-C’s attempt to ensure the efficiency of destroyer machinery by circulating Yarrow’s designs among other builders, led to a prolonged conflict between Yarrow and the Admiralty, the firm refusing to bid for several years.

A war crisis with Russia in 1878 showed that intelligence and staff support for the Royal Navy was inadequate. A Foreign Intelligence Committee, which also had war planning functions, was formed. In 1883, it morphed into the Naval Intelligence Department (NID). Despite this organisation s name, it had important staff functions. For example, the NID published classified analyses of questions such as the value of speed versus protection in battleships. For a time its chief was in effect chief of the naval staff, though not designated as such.

In 1911, it appeared that war against Germany might be imminent. Summoned to brief Prime Minister Herbert Asquith, the First Sea Lord, Admiral Sir Arthur K Wilson, explained his war plans unconvincingly. The more plausible representatives of the British Army, including War Minister Haldane, convinced Asquith that the Admiralty needed a new civilian chief – and an army-style war staff. Winston Churchill was moved in October 1911 from the Home Office to the Admiralty as First Lord specifically to solve the perceived planning mess. A War Staff, formed in 1912, was in effect the planning and mobilisation elements of the old NID. The NID survived as an intelligence organisation, collecting both operational and technical information.

During the First World War, critics of the Admiralty organisation argued that it was hopelessly hidebound, slow, and inept. Later the Admiralty was blamed for the failure to institute convoy before spring 1917; thus the reform of that year was justified in retrospect as part of the claim that the new Lloyd George government alone had saved Britain. Reforms included the choice of a civilian, George Geddes, as Controller; Geddes was already famous for his success in disentangling the railway system in France. He was brought to the Admiralty to accelerate naval and merchant shipbuilding, both badly strained. First Sea Lord became Chief of the Naval Staff, with a Deputy Chief (not on the Board) assisting him. New Admiralty departments included Torpedo and Mining (Director, the DTM). Postwar, Gunnery (ie, fire control, headed by the DGD) and Electrical Engineering (Director, the DEE) were added.

The British financial year began on 1 April, so a programme year extended from 1 April to 31 March – for example, the 1912–13 Programme was for ships to be ordered in summer or autumn 1913, the Estimates for that year having been approved by Parliament that spring. Typically, the Admiralty Board decided the programme for the coming financial year early in the year, with the Cabinet deciding on what to submit to Parliament by late March. Because the character of the programme depended on the cost of the ships, some design estimates had to be completed in autumn of the previous year. Thus the basic characteristics of the 1914–15 destroyers were set during summer and autumn 1913.

The builders

The two pre-eminent builders of small fast torpedo craft were Thornycroft and Yarrow, with J S White, more specialist in yacht-building, a distant third. These three firms built the British torpedo boats. J & G Thomson of Clydebank achieved some important successes with private torpedo craft ventures; later it became more famous as John Brown, after it was taken over by the Sheffield steel firm of that name. With the advent of destroyers, firms that specialised in larger ships were given design and construction contracts: the most important at the outset were surely W G Armstrong (Elswick), Cammell Laird, Fairfield, Hawthorn Leslie, Palmers, and Vickers (originally the Naval Construction & Armament Company). Some firms had close relationships with foreign yards, so that foreign destroyers were built to British plans. For example, Pattison in Italy used Thornycroft plans. Vickers owned much of the Spanish shipbuilding industry from 1909 on. Unfortunately, it is rarely possible to be certain that a particular foreign destroyer corresponds to a particular British design.

The situation is made more complex by the loss of some key records. For Thornycroft, an excellent Thornycroft List, compiled by David Lyon, survives in manuscript form at the National Maritime Museum. So does a design notebook compiled by Vickers’ chief designer George Thurston. Unfortunately, many of Yarrow’s papers were destroyed during a Second World War bombing raid. I have been unable to pursue other builders’ design collections. In some cases, the foreign destroyer covers at the National Maritime Museum indicate design origins.

Later British torpedo boats

British builders kept producing larger torpedo boats for foreign customers, and the Royal Navy bought versions for its own use. Yarrow’s 135-foot TB 80, the first British torpedo boat with a turtleback, was based on its 135-foot Falke for Austria. Apparently, the turtleback was an afterthought, because a weight sheet dated 24 July 1886 shows both her original design displacement (105.8 tons) and a new estimate incorporating the proposed turtleback and miscellaneous armament (106.1 tons). The turtleback became an important feature of later British torpedo boats and destroyers. In theory, it threw spray away from the boat, though critics pointed out that a turtle-backed boat tended to dig into waves and that her bridge was often quite wet. On her official trials in December 1886, Falke made 22.43 knots at a displacement of eighty-seven tons. The 1887–8 Programme included six repeat versions of Yarrow’s TB 79 with turtlebacks, TB 82–87. In addition, in 1887, the India office ordered seven slightly enlarged 125-footers. Taken over by the Royal Navy in 1892, by 1898 these were numbered in the torpedo boat series as TB 100–106.