While the cavalry clash was going on, Williams decided that he had gone as far as he could in leading Cornwallis toward Dix’s Ferry. Now, in order to save his own command while continuing to cover Greene’s rear, it was time for him to change to a road that would take him more directly to Irwin’s Ferry, where he could get across the Dan behind Greene’s main body. Since Lee had caught up with him, Williams told him of his plan to change to the new route and ordered him to continue screening the light force’s rear. Williams then moved to Irwin’s Ferry.

Cornwallis was not fooled for long, however, and for a second time his advance party came close to catching Lee’s men at a delayed breakfast. The American troopers had gone up a side road to a farmhouse and were just getting into their meal when shots were heard from the direction of an outpost. At once Lee got his infantry on the way, then went back to support his outpost in checking the enemy’s advance party. The Americans escaped by the skin of their teeth, Lee’s cavalry being hotly pursued by the British dragoons and saved only by having better horses.

By now Cornwallis was convinced that a final, all-out effort would enable him to catch the Americans before they could cross the Dan. All through the day of the thirteenth and into the night the weary British were pushed on by their commander. Several times the British vanguard was within a musket shot of the American rear guard, and it seemed likely that the light troops would have to make a stand. Each time Lee’s troops got away. Just before dusk Lee’s men caught up with Williams. It soon became evident that Cornwallis was not to be halted by darkness, however, so Williams had to keep going, his men stumbling along in the dark over the rough road.

Williams now sent part of Lee’s cavalry ahead to try and connect with Greene’s rear. It was not long before they saw, ahead of them, a distant line of campfires. They were as dismayed as they had been surprised. Greene hadn’t gotten away after all, and here they all were, with the British closing in on them. “All their struggles, all their hardships had been for naught. Now there was only one thing to do; they must face their pursuer and fight.” However, when Williams came up and led them forward, they found that the campfires were indeed Greene’s, but he had moved on two days before. The fires had been kept burning by the locals, who knew that the light troops were coming.

Williams, however, could allow no halt. He had gotten a message from Greene which told him that the main body’s baggage and stores had been sent on to “cross as fast as they got to the river.” Finally word came to Williams from the rear guard that the British had halted, so he could halt too—but only for a couple of hours. By midnight the light troops were pounding on again, their feet breaking the half-frozen ruts and sinking into the soggy red clay beneath. Even though their pursuers were having the same troubles, at times they seemed to be gaining on Williams’s weary troops. Both sides pushed on, and during the whole morning of 14 February neither force made a rest halt of more than an hour.

Then, sometime before noon of the fourteenth, another of Greene’s couriers met Williams with a message dated 5:12 P.M. of the day before: “All our troops are over and the stage is clear . . . I am ready to receive you and give you a hearty welcome.” Williams passed the word down the columns, and the roll of American cheers was so loud that General O’Hara’s advance party could hear them and must have realized that the race might be won by the Americans.

There were still fourteen long miles to go before reaching the river. The news of Greene’s dispatch had so lifted the American spirits that Williams’s troops, like a runner getting his second wind, were giving it their all in this final stretch.

As for O’Hara, for all the adverse sounds of rebel cheers, he was more determined than ever to catch up to and trap his enemy with his back to the river. Equally determined to cross before O’Hara could intervene, Williams sent Lee back in mid-afternoon again to cover the rear and delay the British. Meanwhile, the light infantry pressed forward, having gained on O’Hara’s van: the British had marched forty miles in twenty-four hours, but the Americans had covered those same miles in sixteen hours.

At last, just before the end of daylight, Williams’s leading troops reached the ferry site and loaded up on the boats to be ferried across. The boat transports kept moving the infantry until the last of them reached the other side after dark. By 8:00 P.M. on 14 February Lee’s horsemen arrived and began crossing on the boats that had finished transporting the infantry. Carrington was directing the crossing in person, and it was he who had Lee’s horses “unsaddled and driven into the water to swim across, while their weary riders clutching their saddles and bridles, crowded into the boats.” Lee then recorded that “in the last boat the quartermaster-general attended by Lt. Colonel Lee and the rear troops, reached the friendly shore.” Less than an hour later, O’Hara arrived at the river to find his enemies all safe on the far side. Page Smith summed up O’Hara’s sense of bitter letdown: “All the weary miles, the burned baggage and wagons, the destroyed tents, the short rations had gone for nothing” (A New Age Now Begins). Cornwallis learned of the failure a little later, and with it the not-surprising news that the river was too high to ford and all the boats were gone with the Americans.

Obviously the boats were the key to Greene’s getting his army to safety. The fact that they were where they were needed, when they were needed, is ample testimony to Greene’s genius and the skill and energy of Carrington and Kosciuszko.

Greene had now been driven out of the Carolinas, and no longer was there an organized Patriot force located south of Virginia capable of fighting a British army. Yet, by retreating north of the Dan, the American general had not only saved his army but was still capable of preventing Cornwallis from marching into Virginia and linking up with British forces there to subdue the rest of the South.

Cornwallis and the British now faced a critical operational problem. To get into Virginia he had to cross the Dan and the Roanoke, and there were no boats to make the crossings. If he tried to use the fords on the upper stretches of river, Greene would know of his moves in time to move his army to hold any crossing site. And even if he should outmaneuver Greene, an unlikely outcome in view of the painful experiences of the past weeks, the American could fall back and be reinforced by the troops that Baron von Steuben was raising in Virginia, and would be the stronger in numbers. So there was no way for the British at this time to drive to the north.

The earl’s other problems were formidable as well. In pursuing Greene he had left his main base over 230 miles behind, and there was no way to replace all the stores and matériel destroyed back at Ramsour’s Mills. His army had swept the nearby countryside clean of provisions and forage, and Pickens had reportedly raised some 700 militia with which he could attack British foraging parties or supply trains. Obviously Cornwallis could not stay where he was, either.

He took the only way out left to him. He would make a safe march back to Hillsboro, where the Tory population would surely rally to him now that Greene had been driven out of North Carolina. His mind made up, Cornwallis marched to Hillsboro, set up the royal standard, and issued a proclamation: “Whereas it has pleased the Divine Providence to prosper the operations of His Majesty’s arms, in driving the rebel army out of this province, and whereas it is His Majesty’s most gracious wish to rescue his faithful and loyal subjects from the cruel tyranny under which they have groaned for many years [all were invited to repair] with their arms and ten days provisions to the royal standard.”

Some forty miles away, on the north side of the Dan, there were causes for rejoicing and “enjoying wholesome and abundant supplies of food in the rich and friendly county of Halifax.” There Greene rested his men while gathering stores and intelligence of both friendly and enemy forces. In Greene’s way of thinking, the crossing of the Dan had ended one campaign; now it was time to start another. In spite of his urgent need for reinforcement, he would not hold up operations waiting for them. The high waters of the Dan were subsiding, and Cornwallis might seize the initiative to try new maneuvers against him. Moreover, Steuben’s Continental recruits might be weeks away from joining him. Uppermost in his consideration was the nagging realization that the climax of all his retrograde operations had not yet been reached—his turning back to strike the enemy he had enticed so far from his base, and who now would be weakened enough to be vulnerable to Greene’s masterstroke. In Greene’s mind that time had come. He must now reenter North Carolina and move against Cornwallis with the forces he had at hand.

In short order Greene transformed decisions into actions. On 18 February he sent Lee with his legion and two companies of Maryland Continentals to reinforce Pickens in harassing British communications and foraging parties, as well as keeping down Tory uprisings. Greene’s next move was to send ahead Colonel Otho Williams with the same light infantry force that he led so brilliantly during the retreat. Williams crossed the Dan on 20 February, two days after Lee. About the same time, escorted by a detachment of Washington’s dragoons, Greene rode to meet with Pickens and Lee near the road running from Hillsboro to the Haw River. There he told them of his plans to cross the Dan with the rest of his army and move in the general direction of Guilford Courthouse. Greene then returned to the main army.

Sometime later, Pickens and Lee set out to act on a piece of hot intelligence that told them that Tarleton had been sent to escort a force of several hundred Tory militia to Hillsboro to join Cornwallis. The Tories, a force of Royal Militia that had been raised between the Haw and Deep rivers, were presently en route to join Tarleton.

On their way to locate the enemy, Lee’s troopers picked up two Tory countrymen, who were duped into thinking that Lee’s men were Tarleton’s, an understandable mistake since the cavalrymen of both legions wore green jackets and similar black helmets. They sent one of the Tories ahead to Colonel John Pyle, who commanded the 300-man Tory force, asking him if he would form his men in a line facing the road so that “Colonel Tarleton” and his troops could pass on to their bivouac area for the night. Completely taken in, Pyle not only formed his line on the right side of the road but also took post on the right of the line where he could greet the British cavalry leader when he passed.

In the meantime the Maryland light infantry and some of Pickens’s militia were following Lee’s dragoons, the infantry concealed by the woods through which the road ran. Lee rode down the road at the head of his men, in his own words, passing along the line at the head of the column “with a smiling countenance, dropping, occasionally, expressions complimentary to the good looks and commendable conduct of his loyal friends.” Lee went on to say that his only intention was to reveal himself and his men to Colonel Pyle and suggest that he surrender and disband his men, and send them home in order to avoid harm coming to them. According to American accounts, Lee was about to deliver his surrender demand—having first grasped Pyle’s hand in his role as Tarleton—when firing broke out at the rear of Lee’s column. Evidently some of the Tories at the opposite end of the line had spotted the American infantry in the woods and fired on them.

Lee’s troopers fell upon the surprised enemy with slashing sabres. The Tories were caught like rounded-up rabbits, and the rest of the action, known as Pyle’s Defeat, or Haw River, was nothing less than a massacre. Of the 300 or more Tory militia, 90 were killed on the spot and 150 who could not get away were left “slashed and bleeding.” Lee’s loss was one horse wounded. If Pyle’s Defeat was not a massacre, it would be hard indeed to accept the American assertion to the contrary, since the casualties with their wounds spoke for themselves.

Moral issues aside, the results of Haw River were unmistakable. The Tory populace throughout the region was thoroughly subdued by the news of the action, and few Tories rallied to the royal standard in North Carolina.

Greene kept his word with Lee and Pickens, crossing the Dan to join them on 23 February after his main body had been reinforced by 600 Virginia militia under General Edward Stevens. Greene’s immediate operations were directed toward backing up Pickens with the support of Williams’s light troops while the main army was building up its strength. The buildup was going to take time, but eventually reinforcements would be forthcoming in the form of Steuben’s recruited Continentals and more Virginia and North Carolina militia. In the interim Greene directed his next marches toward Hillsboro.

Cornwallis, at the same time, was arriving at a decision to leave that place—not because of Greene’s latest move but because of the area’s decreasing means of supporting the British forces encamped there. Provisions were running critically short, and Cornwallis’s commissaries were hard put to force more out of a disgruntled people. These were the same people who, after Pyle’s Defeat, had suddenly ceased to provide recruits. Thus it was to Cornwallis’s advantage to move to greener pastures. Consequently, on 27 February he moved to an encampment south of Alamance Creek. This placed him near a junction of roads that permitted moving east to Hillsboro, west to Guilford Courthouse, or downriver to Cross Creek and Wilmington.

On the day that Cornwallis departed from Hillsboro, Otho Williams crossed the Haw River and took up a position on the north side of Alamance Creek, several miles from Cornwallis’s camp on the south side. Williams now led a formidable force, his light troops having been reinforced by Pickens’s command, which included Lee’s legion, Washington’s cavalry, and about 300 Virginia riflemen under Colonel William Preston. Williams’s force closed in its position on the night of 27–28 February, and the next morning Greene moved the main army to a position about fifteen miles above the British camp.

The American commander had no intention, however, of remaining there. He planned to keep his forces in motion and thus keep Cornwallis off balance while the Americans controlled the countryside and continued to gather in reinforcements. At the same time Williams would also be on the move for the same general purpose, and in addition would act as a screening force for Greene’s main army. On the British side Tarleton began to carry out his screening mission in much the same way.

All this shuttling back and forth served the Americans’ purpose in at least one way—they had begun to annoy Cornwallis. He decided on a surprise move of his own, and marched at 3:00 A.M. on 6 March in the hope of surprising Williams. In so doing he anticipated drawing Greene to the support of Williams, and thereby into a general engagement. In the earl’s view, the American commander could not afford to stand off and see his invaluable covering force destroyed.

As usual, the American intelligence was more timely and accurate than British intelligence. A scouting party of Williams’s on another mission on the night of 5–6 March learned that Cornwallis’s army was on the move. When Williams got the report, Tarleton’s cavalry and Cornwallis’s van of light infantry under Lieutenant Colonel Webster were already within two miles of Colonel William Campbell’s (the same red-headed Scot of Kings Mountain) Virginia militia, which was outposting Williams’s left. Williams dispatched Lee’s and Washington’s cavalry to support Campbell while he hurried the rest of his force toward Wetzell’s Mills, a ford across Reedy Fork. Williams got across the ford first, and the swift arrival of the British van brought on the engagement known as Wetzell’s Mills, in which some twenty casualties were taken on each side. Greene was not pulled into the action, but he did move from his last position near Reedy Fork and camped at the ironworks on Troublesome Creek.

After that affair both armies remained inactive for the next eight days. During the period Greene’s most anxious hopes were beginning to be fulfilled. Steuben’s Continentals arrived at long last, 400 of them, under Colonel Richard Campbell. About the same time the long-awaited Virginia militia joined Greene: almost 1,700 men organized into two brigades under Brigadier Generals Edward Stevens and Robert Lawson. Then came two brigades of North Carolina militia, totaling 1,060 men, commanded, respectively, by Brigadier General John Butler and Colonel Pinketham Eaton. While overseeing the reorganization of his army, Greene decided to disband Williams’s force and return its units to their parent regiments, with the exception of Captain Kirkwood’s famed Delaware company of Continentals and Colonel Charles Lynch’s Virginia riflemen, who were attached to Washington’s cavalry to form a legion similar to Lee’s.

Greene now had 4,400 effectives that he could count on to do battle with Cornwallis. The latter’s intelligence, to Greene’s undoubted advantage, had succeeded in magnifying the American numbers to 9,000 or 10,000. If Cornwallis believed the figures, and there is no evidence that he did not, he was undismayed. His 1,900 regulars were all of them seasoned veterans, who doubtless would prove to be worth more than twice their number in battle with American militia.

Greene had drawn his opponent northward, stretching Cornwallis’s supply lines to the breaking point. If he did not strike before the enemy was reinforced, his strength would dwindle away once the militia had served out their six-week commitment. Moreover, both he and his enemy had stripped the area of food and forage, and neither force could sustain itself in the region for more than a few days. Greene knew that his enemy, just recently moved to New Garden a few miles away, would not refuse the challenge to fight a pitched battle once the Americans had taken up a fixed position.

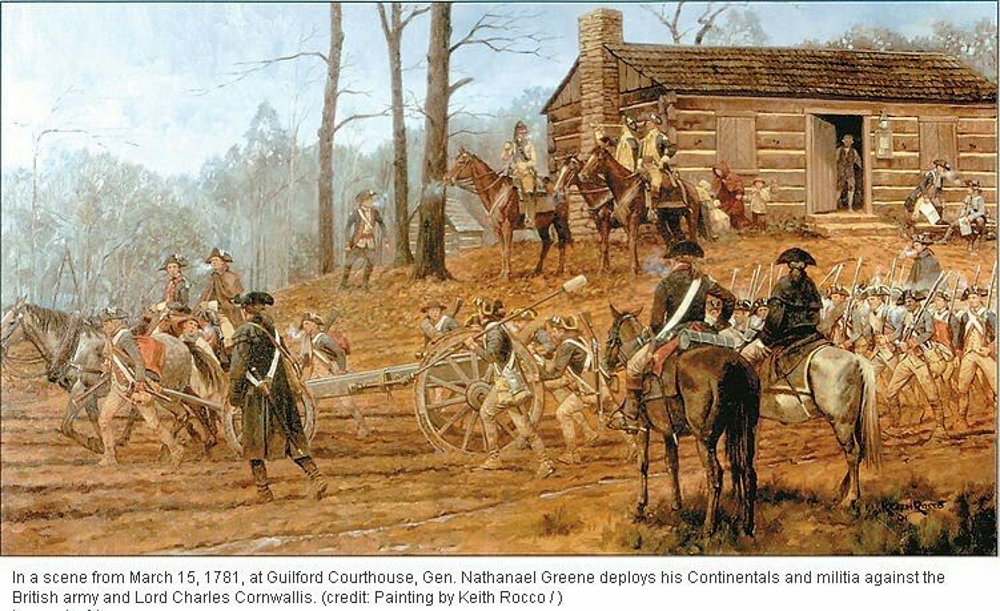

No doubt Greene had in mind just the locale that would favor his battle. He had studied the terrain when he had first stopped at Guilford Courthouse, when his council of war had talked him out of fighting. Now there was no need for a council. Greene moved on 14 March to take up a defensive position at Guilford Courthouse.

It has been commonly accepted that Greene deployed his army for battle using the same tactics that had worked so brilliantly for Morgan at Cowpens. The point, I think, has been very much overstated. It is true that Morgan advised Greene, in a letter dated 20 February, in regard to deploying his forces when confronting Cornwallis in battle, but there is no evidence to show that Greene unthinkingly adopted Morgan’s every suggestion, even though his three-line-deep deployment might appear on the surface to be a carbon copy of Morgan’s. The terrain on which Greene made his dispositions was markedly different in character from Cowpens. Morgan had been successful in South Carolina because he fitted his firepower to the terrain in such a manner that he could observe and control his troops throughout the action. The terrain of Cowpens, with its excellent all-around fields of fire, allowed Morgan to do just that.

The terrain at Guilford Courthouse denied Greene any such freedom of action. Its most striking feature was the dense forest that dominated the area, with the exception of the few clearings that offered fields of fire, usually limited to the immediate front. If the Americans were to adopt Morgan’s three-line deployment, the terrain dictated that there could be no mutual support between the lines. Nor could the commander or his senior leaders even see the first two lines, because the troops would be out of sight in the woods.

For all that, Greene proceeded to deploy. The road from Guilford Courthouse to New Garden bisected the positions of the two forward lines. The front line was composed of the two North Carolina militia brigades of 500 men each: Butler’s on the right of the road, Eaton’s on the left. The right flank of the line was covered by Washington’s legion, with his cavalry on the extreme right. His infantry, composed of Kirkwood’s light infantry company and Lynch’s Virginia riflemen, was formed in a line that was angled inward in order to provide enfilading fires against the attacker. On the left flank Lee’s legion was deployed in the same manner as Washington’s. The cavalry covered the end of the flank, with the legion infantry and Campbell’s riflemen formed in line facing obliquely to enfilade the main line from their position. Captain Anthony Singleton, with two of Greene’s four six-pounder guns, was in the center, with his guns positioned on the road and laid to fire across the clearings to their front.

The second line, about 300 yards behind the first, comprised the two Virginia militia brigades of 600 men each: Stevens’s on the right of the road, Lawson’s on the left. The second line was deployed entirely in the woods, with connecting files posted in the rear to facilitate contact with the third line.

Greene’s main line of resistance was his third line, 550 yards to the right rear of the second line. In order to take advantage of the high ground west of the courthouse, this line had to be displaced westward, with only about half of it directly in the rear of Stevens’s brigade. Two brigades of Continentals made up the line. On the right was Huger’s brigade of Virginia Continentals, 778 men: Colonel Green’s 4th Virginia on the brigade’s right, and Hawes’s 5th Virginia on its left. The other brigade was the Maryland Continentals, 630 men under Otho Williams: Gunby’s 1st Maryland on the brigade’s right, and Ford’s 5th Maryland on the left. Captain Samuel Finley’s two six-pounders, the other half of Greene’s artillery, were positioned in the center, in the interval between the two brigades. Greene remained with the Continentals throughout the battle.

Along with the terrain and the disposition of the troops, several other factors are noteworthy. Greene had put his entire army in the three lines. There was no provision for an army reserve of any kind, whereas the terrain of Cowpens had permitted Morgan to hold all of his cavalry in reserve. The question of Greene’s lack of a reserve has been well addressed by Boatner: “It would appear that he should have been able, however, to set himself up a general reserve, either from the flanking units of his first line, or by eliminating the second line and using these flanking units as a delaying force between the first and last lines” (Encyclopedia of the American Revolution).

The quality of Greene’s troops was decidedly uneven. At opposite ends of the spectrum were the battle-hardened veterans such as Kirkwood’s Delaware company and Gunby’s 1st Maryland Continentals; on the other end was the North Carolina militia, which could not be depended upon at all to stand up to British bayonets. Two units, the 5th Maryland and some of the Virginia Continentals, were getting their first taste of combat.

Greene was well aware that his front line, much like Morgan’s second-line militia at Cowpens, would vacate the premises shortly after the shooting started. That is why he walked the line of his North Carolina militia, exhorting them as best he could and reminding them of his basic instruction: Get off at least “two rounds, my boys, and then you may fall back.” In that exhortation lay another case of the difference in the terrain of Morgan’s and Greene’s battles. Morgan’s militia could file off around the left of the Continental line behind them and reform to reconstitute a reserve. Greene’s militia had no place to go except the woods around and behind them, so when they “fell back” they would vanish off the earth, as far as their further participation in the battle was concerned. Consequently, the only recourse left to Greene was to order, ahead of time, the Virginians in the second line to open their ranks and let the Carolinians pass through. He also made sure that Washington’s and Lee’s flanking units knew that they should fall back and take up positions on the flanks of the second line.

His instructions given and his inspections made, Greene rode back to his command post behind the third line. The morning was clear and cold under a cloudless sky. It only remained now to sit tight and await Cornwallis’s advance.